Taking Off on One Engine: A Confession

Last week, I posted a follow-up from this runway excursion at Portland, focusing on the cockpit voice recording which proved that the pilot knew he had only one engine before deciding to take off.

This week, Rudy is taking control for the blog to tell us about the time that he took off on one engine. Unlike our pilot of the previous post, he was not safely parked in front of an FBO when he and his first officer discovered that they had an issue. But I’ll let Rudy tell the story.

Taking Off on One Engine

by Rudy Jakma

This is a confession.

I HAVE made a single-engine take-off in a Citation.

The circumstances virtually eliminated any other option, it would have meant abandoning a nearly brand-new Citation, then spending a lot of cash money in US $$$ to get home without the aircraft. It would probably have to be written off. And it is unlikely that the insurance would have paid out.

It must have been in 1980. We were with my boss in Africa on a sales trip. We were in Kinshasa, Zaire. At that time it was a very unwelcoming place, not a place to stay unless you had access to a house in a walled compound or a hotel with guards at the gates. We were told that we were not to leave the hotel after dark, even the hotel itself was not a totally safe place for Europeans.

The parking fees were astronomical and Zaire had not paid its bills to the international telecommunications industry, which meant that there was no telephone connection with the outside world.

The Citation had been parked near the Air Zaire maintenance base, but there was no maintenance carried out and there were no engineers either.

A few DC-8s were parked in an open hangar, engine cowlings open and everything under a thick layer of dust and dirt. The only other aircraft that looked in decent condition was a Mitsubishi MU-2; a forlorn American, the only other person there, identified himself as representing the owner.

The Mitsubishi had developed a (minor) technical problem. The crew had obviously somehow managed to contact the owners who had dispatched an engineer with spares and a toolkit. When the engineer arrived, he was immediately arrested: charged with importing aircraft spares and a toolbox, with the intention to work without a work permit. Diplomatic intervention secured his release, but the spares and tools were confiscated. The American representative did not hold out much hope that this aircraft would ever fly again.

Our diplomatic clearance to fly to the next destination, Dar-es-Dalam, had been refused. Our employer managed to get an airline reservation and instructed us to meet him in Nairobi. And so, the next morning, we prepared the Citation for a positioning flight to Kenya.

It did not work out as planned. The right-hand engine would not start. Pushing the starting button only produced a lot of rattling and clicking of relays, that was all.

We were in a pickle, stranded at an airport, in a country that was nearly lawless. We had checked out of the hotel and had no way to contact anyone.

We discussed our limited options. Everything had to be paid for in cash: taxis, hotels, landing and parking fees. Credit cards were not accepted, only the US “greenback” would do. We would run out of funds in a matter of days.

We had a list of authorised Citation repair shops with us. The nearest one was Air Service Gabon in Libreville.

We looked at the performance charts and compared them with the available runway length. This was about 5,000 metres. Next, we marked a distance within which we had to reach Vr with enough remaining distance to stop.

(We did not just hop in and try, we very carefully worked it out!)

Outside we could see the airport’s fire engines. There were two, but one was sitting on concrete blocks and the other would not start.

Still, there was no choice. So, yes, we taxied to the runway and accelerated. My copilot very carefully fed in the power on the left-hand engine while I did my best to keep the aircraft on the centreline. The Citation had no separate nosewheel steering, it was all done via the rudder pedals. Slowly the speed increased. The rudder became effective, I could hold the straight line with full power on the live engine, we reached Vr and we got airborne.

Our problems were not over. In the tropical heat the performance was not great, the aircraft did not climb very well. At our low altitude we were using far too much fuel.

Pressing the starter button had the same effect and to make matters worse, we lost all VHF communication.

We knew we needed at least 200 knots indicated airspeed for a windmilling start of the right engine; however, the aircraft was accelerating only very slowly. The situation was still not good.

Then we saw a valley ahead, the terrain dipping to a lower altitude.

We made a gradual dive into the valley and our speed increased: 150, 160, 180, 190, 200. Ignition ON and power level to idle. The engine turbine temperature climbed, as did the RPM. Both engines were running and we quickly climbed away. As we reached FL200 (20,000 feet) we heard the frantic calls of ATC. The VHF had come back to life. The controllers had seen our slow acceleration and then we disappeared below tree-top level: they must have been certain that we had crashed.

Their relief was short-lived when we announced our intentions to proceed to Libreville.

“You must return, you have no diplomatic clearance to go to Gabon! You must land and apply for clearance”.

We replied that we had a technical problem that could only be repaired in Libreville. “We cannot be expected to plan our technical problems in advance.”

Looking back, and admitting that my critique of the other crew may sound more than a bit hypocritical, I am still convinced that we were in a very different situation. We could not simply call an engineer to come over and solve the problem, we would have left a nearly brand-new corporate jet to rot away.

We also would have had to spend hundreds of $$$, just to leave Zaire. If we stayed, we risked being robbed or arrested. There was not a glimmer of hope of finding a mechanic there.

Yes, it was a very risky effort but we had no passengers and not a lot of options, either.

After some reluctance, the Kinshasa controller handed us over to Brazzaville. Again, there was hesitation to allow us to continue but eventually we won the argument. Brazzaville asked us to contact Libreville on the HF (High Frequency radio). The HF had not yet been installed on the Citation but we agreed and pretended that we had one.

We cruised quietly towards Libreville at a high level. Even in the tropics, it is very cold above FL 330. The windshield of the Citation is very thick plexiglass and heated by the application of bleed air from the engines. On the ground, it was around 33° C, with a humidity of more than 90%.

Eventually we were within VHF range of Libreville where we spoke to a puzzled and suspicious controller who refused us entry into his airspace.

He announced that we must divert or return to Kinshasa as Libreville was closed to all traffic. Unsympathetic to our supposed problems, he told us that we could apply for clearance to land at Libreville from Kinshasa in a few hours.

Eventually, we convinced him that we were legitimately in need of technical support. He cleared us to enter Libreville airspace and eventually to land.

During descent and approach the power is low, and so is the amount of hot air over the windshield. As we landed, the windshield, still maybe at 10° or 15° in temperature, started to fog over in the humid air, inside and out.

When we shut the engines down, the windows misted over completely and it was virtually impossible to see anything. As we attempted to peer out, a bizarre vision appeared through the fogged up windows.

A red carpet was rolled out to our aircraft. Then a brass band in immaculate uniforms began to play and marched in our direction.

Just as we were wondering if Air Service Gabon was truly in desperate need of our business, a few whistles sounded. The brass band retreated in disarray and the red carpet rolled back up.

There were urgent raps on our windows and the door. An officer in military uniform told us to start the Citation up again and taxy to the hangar.

“We still have to clear customs and immigration,” we protested.

“You are now cleared, go to the maintenance area at once.”

We had no choice but to comply. The windscreen had warmed up, we could see again, the right engine still would not start so we went to the maintenance area on one engine.

After we shut down again, a Fokker F28 jet airliner flew past overhead, flanked by two Fouga Magister fighter trainers.

It became clear what had happened:

In many African countries, when the President travels, all roads are closed a few hours before he will pass, the same with airpace and airports. The F28 was the Presidential jet, carrying President Bongo.

Of course, we arrived during the curfew. The organisers thought that the arrival of a business jet could mean only one thing: it carried the President. No one had counted on another private jet arriving around the same time.

Now safely parked at Air Service Gabon, we were hopeful that we could get the starter issue resolved quickly. This was optimistic. They searched for the defect in the tailcone; however, they could only stay in there for short periods of time as the air inside the tail soon became unbearably hot.

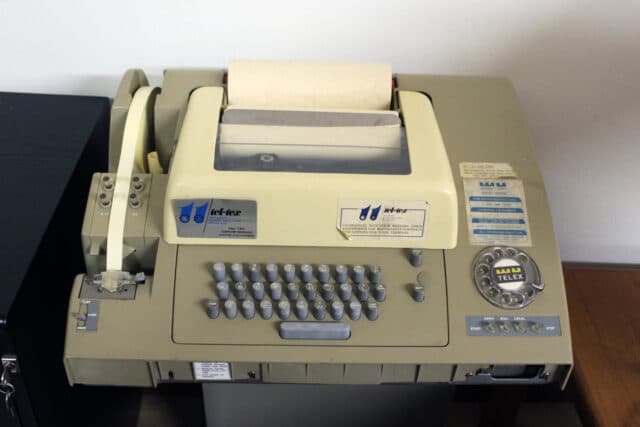

The problem with the starter was very minor, but it required our engineer at Schiphol to guide the engineers at Libreville. Air Service Gabon had a telex. Computers were far and few at the time and they still ran on MS DOS. Windows and the Internet had not been invented yet. The engineers were sending messages back and forth via the telex.

Eventually, the Schiphol engineer worked it out from afar. On the Citations, the starting cycle is cancelled once the engine is running and on earlier models, such as this one, it determined that the engine was running by the fuel flow. When the engine is running, pressure builds up in the fuel supply line. This activates a pressure switch located in the bottom of the wing root which cancels the starter and reverts to generator mode.

Unfortunately, this switch was stuck, sending the message “engine running” to the starter, which prevented the starter from being activated.

Soon after that, the system was modified so that the starter cut-out was determined by the generator rpm.

We did a test flight, accompanied by a French engineer. The Citation didn’t have a jump seat, so he just sat down on his haunches behind us.

When it all proved OK, we flew a victory roll. The French engineer was not impressed. Once we landed, he threw open the door and ran out screaming about the dangerous Dutch pilots: “Kamikaze Hollandais, un tonneau, un tonneau!” (tonneau means roll)

The next day we were ready to depart for Nairobi but we thought we should inform customs and immigration. We searched the deserted terminal building until we found a bare room with a few men playing cards. We explained our situation and the men burst out laughing.

They were prisoners and we had entered the airport jail. It can’t have been that bad: the door was not even closed.

Thanks to our new GPS, we were able to forgo a planned fuel stop at Kigali: Sabena was supposed to supply the fuel, but we were told in no uncertain terms that we would be less than welcome after our unauthorised flight to Libreville. We reduced our speed to the maximum economical airspeed (about 295 knots true airspeed) at as high a level as possible and arrived without ever having to touch our reserves.

Thanks for Rudy for sharing the story with me and I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did!

In 2003, whilst undergoing a Citation Bravo conversion at FSI at Wichita, we were told about this incident and actually practiced it in the Sim.

That’s a fantastic story, and a great addition to the “Rudy” category of this blog!

Another big difference to the previous story is that this was an actual two-pilot operation, with both pilots in the cockpit sharing the workload, both during the preparations and the actual take-off. I imagine it’s much easier to keep the aircraft under control when you don’t have to carefully increase the power at the same time!

I never knew that this story had leaked out. Maybe the engineers let the “cat out of the bag”.

No, I do not recommend this, “don’t do this at home” is more appropriate.

My main excuse, as you no doubt have read, is that we really were in a very difficult situation and the chance that the Citation, at the time not even a year old, would eventually end up as scrap, was very real.

My copilot had been trained for his rating at the American Airlines Flight Academy, I had received my training at Flight Safety International at Wichita, Ks. We were both fully type rated.

We discussed the situation, went over the performance charts and decided that we would have a good chance of reaching Vr with at least 1000 metres of runway to spare. V1 did not feature of course, but we would have had room to stop..

Nosewheel steering on the Corvette was by a small handwheel at the left of the cockpit. At low speeds the feedback from the rudder was virtually none, the pilot had to carefully coordinate the two to be ready to release the steering tiller after 60-70 kts. After that the forces exerted on the steering could damage it. When attempting a single engine take-off with the Corvette (NOT recommended !), too high a power setting on the live engine could quite easily cause the aircraft to go out of control. Which evidently did happen. The big question is: why didn’t the pilot close the power, slam on the brakes and return to the ramp? Maybe he had been hoping to do a “windmilling” start on the dead engine, not even realising that this would lead to a serious overtemperature and engine damage unless he had 200 kts IAS.

The Citation had both nosewheel and aerodynamic steering via the rudder pedals. My copilot, actually qualified to act as a captain, he just needed a bit more time before upgrading, was an experienced pilot and we had been working together for a long time.

Even so, I am aware that what we did was an act of desperation and we would never have dreamt of doing it under different circumstances.

And the barrel roll?

I was taught how to do it by a former US Air Force fighter pilot, the late Colonel Martin J. (“Barney”) Barnard. He had survived active service in WW2, Korea and Vietnam before he became a demo pilot with Cessna Citation. He was a real-time ace and so even that was not as ad-hoc as it may seem.

If this was 1980, MS-DOS had not yet been released, and GPS was not available for civilian use.

I admit that your motivations were a lot more compelling than those of the pilot stranded in Portland.

YEEEEEOOOOOSSSSSSSSSS! YES!YES!YES!

Seriously though, you were in a VERY different situation.

It was not far from a life-or-death situation anyway, and you obviously very carefully planned it out and performed it.

I’d fly with Rudy any day… two engines or not.

Robert,

Sorry the computers HAD been invented, but yes, the GPS was not.

That is a typo.

For our navigation we used VLF-Omega, GNS 2.

It was very advanced for its day and as long as it received a sufficient number of stations it was very accurate.

GNS: Global Navigation System.

What a great story, I’m glad it worked out so well. For a while there it was starting to sound like a chapter out of Hemingway’s life. You write well, the technical details and the cultural observations and the humor, great story. Thank you.

Rudy,

I would love to have a glass or two and swap Africa stories with you. After 40 years, it is still hard to believe we got away alive from some of the situations Africa threw at us.

Funny, I read the typo GPS as GNS. Either my dyslexia or what I expected the nav system to be.

One of my friend’s sons is a Cessna rep. I forwarded this report to him. Thanks for sharing.

Excellent story, well written and enjoyable!

One thing: I sketched a picture of a lawless and dangerous country. The situation in many “developing countries” is a direct consequence of colonialism. After destroying an infrastructure that in many areas existed, often very efficiently, the colonial regimes left their former possessions in a total mess. Even creating “countries” that consisted of cultural entities with profound differences, and with borders that ignored former tribal areas. The mainly European countries had allowed a small, but powerful elite to amass enormous fortunes, often by brutal mistreatment of the indigenous population, and left nothing but chaos behind.

I want to set that record straight: the mess that we encountered in Zaire, formerly Belgian Congo, was not really caused by the people of that country.

Thank you for adding this post-script. It is essential that we understand the impact of past decisions.