Part 2: Don’t Try This At Home (Rudy’s solo cross-country)

I’m so pleased to be able to share with you the second half of Rudy’s story of his first cross-country solo!

In part one of my confessions of an old bold pilot, I wrote about my early flying. When you read the rest of the story, you might wonder how I ever became a commercial pilot, logging about 22,000 hours in the process. The only thing I am proud of is that I kept totally calm and composed, when in fact I had good reason to panic.

I was living in Nigeria, in a place called Ikeja. It was a bit of a left-over from the colonial days, with nice houses in lush gardens, surrounded by hibiscus, bougainvillea and palm trees. There was a country club and Kingsway, a romantic looking supermarket.

Idyllic if you could afford it. My rent was paid for by the company, which was usual in those days.

I spent most of my free times at Lagos Flying Club, based at a grass strip called KiriKiri.

After completing my dual cross-country flight my instructor, Colin Horsfall, signed me off for my solo cross country, but the rainy season had started and the weather was not good.

Then, the next Saturday the sky looked a bit less grey. I drove to the airport. The rain had stopped, there were a few breaks in the clouds. I went to the Met. Office for a weather briefing.

My VFR maps had large white areas, due to “incomplete survey”. In those blanks were the ominous words “Relief data incomplete”. There were no other maps available at the time.

The forecaster on duty explained that a large area of bad weather had covered the south-west of the country, but that was now clearing to the west. I might still encounter some broken clouds at 1,000 feet but it should clear rapidly. I thanked him, filed my flight plan and went to the ramp to prepare the aircraft.

This is where I went off the rails, completely and utterly.

Until then I had been a cautious, primarily straight-and-level pilot. I did not even like stall exercises, a steep turn with 45 degrees bank was enough excitement for me. Now I went completely out of character.

What follows here is not something I can be proud of. I broke the rules – in a major fashion. And worse: I did not even realise that I was embarking on a really dangerous adventure. Irresponsible. unprepared, in fact. If I were to read about another pilot, doing the same, I would not spare my sarcasm and critique. But it was ME, myself, and everything really happened exactly as I will describe. I got away with it, I was lucky and can tell the tale in atonement.

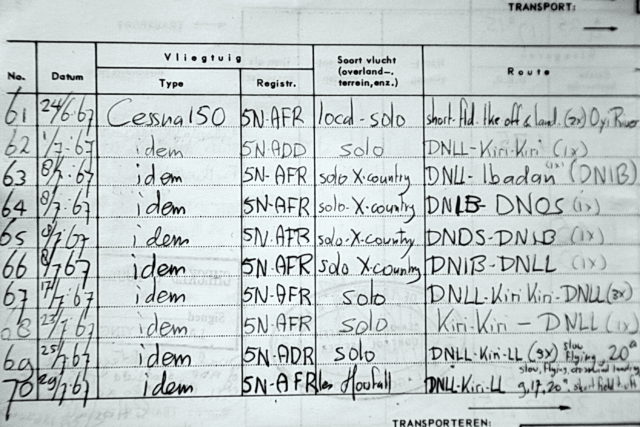

Which was: as a student pilot, having arrived in a new country, a country I had barely heard of a half year previously, in an equally unknown continent, with a grand total flying time logged of 38 hours 40 minutes, I set out on a cross-country flight over virgin jungle, large parts without features and hardly any landmarks. My map had blank areas, I did not carry a useable ADF or VOR. The weather was barely VMC and my track would be across an area I was unfamiliar with. The ATC transponder had not even been implemented yet, it still was mainly in use in the air force, known as “IFF”. I did not carry survival equipment. The aircraft, to be resprayed yellow later, on that occasion was still painted green.

The date was July 8, 1967.

I had my heart set on completing the cross-country flight and did not even pause to consider why my instructor had not shown up to see me off.

The Cessna 150, 5N-AFR was refuelled. I did the pre-flight, cranked her up and asked for taxi clearance.

I received a “special VFR”, meaning that the weather actually still was below the criteria for a visual flight within controlled airspace. It includes the admonishment to “remain in sight of land or water”. Having repeated the clearance I was now cleared for departure, first stop Ibadan (DNIB), about 45 minutes flying, nearly north of Lagos.

If I had had a bit more experience, or common sense, the fact that I ran into a low, broken overcast nearly immediately should have been a warning. But, I reminded myself, the forecaster had told me that I might encounter a bit of cloud during the first stages. And so here I was; my first solo cross-country started with what is known as “scud-running”. There are many such flights that have ended up in the accident reports, I carried on regardless.

Another warning sign that I chose to ignore was that I should, under normal circumstances, have been able to see the Lagos Lagoon to the east, a large inland expanse of water not too far to my right.

Somewhere halfway was the only landmark, a radio mast painted red and white. Otherwise there just was the jungle canopy below and nothing else. No roads visible, no villages. But right on cue, there was the mast. And the low clouds lifted. It was going to be all right, or so I thought.

By the time I arrived at Ibadan, the weather had really improved. No low clouds and a visibility of about 5 or 6 miles. Looking good. I contacted the tower, landed, paid my landing fees and soon was on my way, next destination Benin City.

Benin was the capital of the old kingdom of Benin. The former French colony of Dahomey, west of Nigeria, with capital city Cotonou, took that name to replace the old one with. Benin City is east of Lagos, about 1 hour 50 flying.

For the first half hour the flight went well enough. That changed when the cloud base started to come lower, lower and lower. At the same time, I crossed ridges of hills that increasingly narrowed the gaps between the treetops and my undercarriage.

To make matters worse, I was now in an area where my map was useless. It just showed a white grid, not much more than longitude and latitude. The hills certainly were not on it.

I had not yet taken leave of all my mental faculties. I realised that I now was running into real danger. The ridges were the boundaries of valleys. Valleys full of dense tropical jungle, a landing would be an inevitable catastrophe. I had no experience flying on instruments, getting trapped in a valley would have meant a near-certain death. I had to make a decision. And soon.

The cross-country required two landings away from home base. I remembered that we had visited an aerodrome called Oshogbo when I did my dual cross-country flight. Oshogbo was north-northeast of Ibadan. It was in a map segment that showed all the land features. Better: nearby was a broad, sandy river bed, well visible from the air even though I would approach it from a different direction than the previous time.

I had read everything about air navigation that I could lay hands on. After all, I was working as a dispatcher. By now I had mastered the fine art of making a navigation plan.

I put my navigation kit on the seat beside me. First. I took out my protractor and flight computer, worked out my estimated position and drew that in the white area where I hoped I would be, then extended it to a plotted position in five minutes’ time. The flight computer in those days was used by all pilots, it was more like a circular slide rule. From there, I plotted a track and time to Oshogbo. That all with a very limited flying experience, in a moving aircraft without autopilot. I had no time to get nervous, I just had to do it.

I called Benin on the radio. No reply, out of range. Ibadan gave the same result. But a Nigeria Airways flight was talking to Ibadan. I called them with the request to relay that I was diverting to Oshogbo due to weather. The crew seemed a bit surprised, but did pass on the message. At least, ATC knew what I was doing and where I was planning to go.

My time was up, at the estimated time over the assumed position I turned left, in a north-westerly direction and headed for Oshogbo.

Perhaps this can be regarded as the one and only truly outstanding feat of this flight. I had not lost control of the situation, had worked out a new course from an estimated position, all done by “dead reckoning”. Well, the reckoning may have been dead, I certainly was not. Exactly at the estimated time of arrival Oshogbo came in view. First the sandy riverbed, then the aerodrome itself.

A few men were there whom we had not met the previous time. From their reaction it appeared that not many aircraft landed at their strip. They were forecasters. I asked for the Lagos forecast. They looked at one another. Their radio and other communications had not been working for a long time. They did not have any data to base a forecast on, no synoptic charts. All they could give was the local weather. Visibility, cloud cover, wind, temperature, dewpoint and QNH. Not much more.

At least they stamped and signed my log book as proof that I had been there, a photo and a friendly wave and off I went again, back to Lagos.

My track brought me close and east of Ibadan. I made radio contact and reported my intentions. It was not good. Ibadan informed me that the weather at Lagos had deteriorated, in fact it was still deteriorating. I was a bit apprehensive, but the weather still was not too bad. The radio mast came already in view, but then things changed. I could see the lagoon in my ten o’clock position, but where Lagos Airport should have been was nothing but dense black cloud. Very soon I flew into heavy rain and could barely see forward. A hasty retreat was in order, back to Ibadan where I landed for the second time that day.

As I sat in the waiting area of the airport two men entered. They were dressed in pilots’ uniform. It turned out they were helicopter pilots of Aero Contractors, the employers of my instructor. Two French-built Alouettes were on the parking.

This was getting serious. If two professionals in helicopters could not make it back to Lagos, what chance did I have?

I was the only European in the waiting room. They eyed me with weary looks. I was dressed in a uniform-style shirt. They recognised the Cessna and came over for a chat, thinking that I was at least an experienced pilot. When I confessed that I was a student pilot on a solo cross-country their eyes widened. “Who is your instructor? How could he have allowed you to depart in this weather?”

At the mention of the name Colin Horsfall their mouths fell open. “Does he know about this?”

No, he did not.

“He sure will have something to say when you get back.”

A few hours went by, the heli pilots were getting anxious to get back to base, but the weather reports were still not encouraging.

It was already starting to get late when, finally, they decided that they could chance it and they got ready for departure.

I had another brain wave, another that I should have ignored.

That was the same speed the Cessna was capable of. “Can I follow you? If I keep you in sight I would have a good chance making it.”

I am not sure why they agreed, but soon we all three were airborne. The first fifteen minutes or so I was able to follow the Alouettes, then clouds moved in again, I lost them out of sight and I was on my own.

This time I barely saw the radio mast. It was too risky, I decided to return to Ibadan.

A nasty surprise: the weather had moved in over Ibadan as well, return was no longer an option.

I called the helicopters. They were finding navigation difficult, too.

Now there was only one option left: I called Lagos Tower and declared an emergency.

The helicopters were told to hover over their last known position. The airport was closed to all traffic until I landed. Fortunately, the weather was so bad that there was not much traffic in the first place.

I was given a QDM, a bearing to the airport, which I only saw when I was virtually overhead. I circled, landed. The other aircraft (all commercial and, apart from the helicopters, under IFR) were making their approach and I taxied to the light aircraft parking, which was drenched. There were several inches of standing water, it was like tying down a float-plane.

I had to take off my socks and shoes to wade back to the car park.

Strangely, I did not hear back from the authorities about my flight, but I heard a lot more from Colin who was absolutely furious with me (and rightly so!) and suspended me from flying for a week. Not that it mattered much, the weather was not good enough for flying anyway.

-Rudy

Well, crikey. The week’s wait was worth it.

I knew you’d survive, of course… but I’m also happy to hear there was no blood or bent metal.

Great tale, great pictures, thanks!

That might not have been as splashy as Sully’s exploit, but keeping cool enough to calculate a working flight path while flying a C-150 with less than 40 hours of experience is no mean feat. (I trained on the C-150 a few years later; my recollection is that while it wasn’t exceptionally touchy, it didn’t fly itself.)

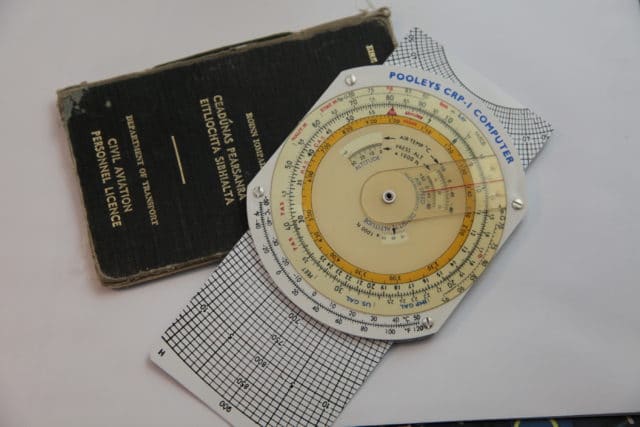

I remember those calculators well; in addition to normal functions of a circular slide rule, they had an analog vector calculator — although I don’t know how useful it would have been given a shortage of weather information. (I see the vector calculator in your picture; did your device also have conversions (pounds/gallon, density altitude, indicate/true airspeed) built in?) I’m still annoyed that I dumped my E6B during a move; just because I hadn’t used it for 14 years didn’t mean it had no historical value — although I see Wikipedia claims it’s still in use for flight training, so it wouldn’t have much get-off-my-lawn value.

Fantastic story Rudy. Hope to read more from you. Also what a fantastic site Sylvia. Keep it up, I enjoy every article (mostly the crash analysis).

Kind regards from Ben from Holland

Fantastic story

Sylvia is running a fabulous aviation blog. Professional, all her facts checked (I never do, I just work from memory) and with room for some reactions; anyone can write comments. My comments are intended to give a bit of insight in the world of (commerical) aviation in the hope that people can either learn from it, or just give a bit of enjoyment.

Sully achieved a miracle. As I mentioned: He had a few things in his favour like weather and gliding distance. That was the “luck” factor. But he managed the situation he found himself in with a truly superhuman amount of skill and professionalism.

No, I am not in that category. Nowhere near. I was just an amateur being very very naive, ignorant and I suppose that I never really gave the danger factor a thought. So overconfident on top of all that.

The “luck” factor in my case was that I did not suffer any technical failure.

Some months later, a Sabena 707 cargo flight crashed on a non-precision approach, probably about 10 miles north of the airport. They got their MDA wrong, I suppose. The aircraft caught fire and burned out.

With two ATC controllers (by that time I had my PPL) we took an aircraft and went to have a look.

So: A week or so after the accident we were looking for the crash site of a large aircraft, in a known position, on long finals not far from the airport.

But the jungle hid it well. The fire had long been extinghuished and a copse of dead trees can look deceptively like the ribs of a wrecked aircraft. If I had gone down in that jungle, no ELT, no emergency equipment at all, how would anyone find a downed C150? It was even painted green! And even if so, no hospital nearby. Unless one counts in the priests and monks of the lepra colony of Oyi Rivers, but that was nowhere near my flight path.

Later, I did fly to Benin City in the club Cherokee. We visited a few villages in the jungle and even were received in audience by the Oba (king) of Benin.

With my kind regards in return to Ben from the Netherlands.

Are you a pilot yourself? If so, where?

BTW Chip, all those flight computers insofar as I know had sectors for conversions: gallons to litres, TAS, Celsius to Fahrenheit, all that sort of things.

No unfortunately I have not yet had the privilege of flying myself. I’m at most a hobbyist flight simmer with no actual flight education. I lived in Hilversum for years and still work there so funny to read about your career and flying experiences there.

I do really love these vivid stories and reconstructions though. Love the National Geographic series too.

Cheers!

Cheers to you too, Ben !

In my days, the NLS, then the undisputed masters of Hilversum aerodrome, issued a very nice sticker, to be placed at the inside of a car window.

You will understand the Dutch:

“The weg is vol, de lucht is vrij, leer vliegen.”

The road is full, the sky is free, learn how to fly !

Well, the roads are still full and the skies are no longer free. But still, the magic has not gone completely yet.

Freedom of the sky? It sometimes works in a car.

A private pilot, in his car, was far exceeding the speed limit on a Dutch motorway.

The cop who stopped him was trying to be funny and asked for his pilot’s licence.

Which, to the policeman’s surprise, was promptly produced.

So the quick thinking cop’s response was: “Okay, and can I see your low flying permit ?”

Very interesting … did you eventually complete your cross country solo?

What other stories do you have? We look forward to them!

Well Jonathan,

If you read the story of my cross-country flight:

It is an exercise in which a student pilot has to demonstrate his / her ability to navigate independently between a few airports or aerodromes, located at a certain minimum distance from the home base – and from one another.

On my particular flight I had planned Lagos – Ibadan – Benin City – Lagos.

But, as I explained, I could not complete the leg from Ibadan to Benin City. So I diverted to Oshogbo. And got my logbook stamped to prove it.

Only, due to weather I had to land again at Ibadan.

But still, even if I had been foolhardy in the extreme, I had fulfilled the requirements. So: the answer is yes.

The requirements are for two different destinations, so the second landing at Ibadan did not count. But Oshogbo was the second one. Plus, of course, Lagos Ikeja, the home base and final destination.

An airport, insofar as I am concerned, has a decent runway suitable for commercial operations and some form of control tower, but need not necessarily be “controlled”.

An aerodrome is a designated landing place, mostly unpaved or of dimensions unsuitable for commercial operations. As a rule uncontrolled, at best with some form of aerodrome advisory service.

These are my own definitions, feel free to correct me.

Other stories? Plenty but my solo cross country is probably the best.

Eventually I got my CPL, earned money with banner towing.

I did not really take many photos then. Anyway, this is Sylvia’s blog. She no doubt has enough stories to keep us all reading !

Thanks Rudy, for the “near miss” story and great history and pictures! I am here for Sylvia’s wonderful analyses of course, but this was a nice diversion too-glad to hear it ended well! Great sign off too, very funny.

Very intrigued by this story as I was LFC instructor at Full time 1958/69 at Kiri Kiri wonder whether we ever met ?

Bassey and Erkop worked at the airfield then and we had Russian AA guns around the perimeter.

Strange days

Clive Boarder

Sorry I meant I was ther 1968/69

Clive Boarder

Clive,

Sylvia alerted me to your comment. Very interesting.

I left Nigeria in ’68. Probably before your arrival.

By that time Ojukwu’s dream of an independent Biafra was over.

Russia had supported Biafra, but not openly. The USSR sent a few bombers to help hem but they were impounded by the Federal Nigerian Government and parked at Lagos Airport across from the Pan African ramp. When I returned to fly a Learjet (5N-ASQ) they were still sitting there, half covered in bush that had grown up in the meantime.

Russia also sent MIGs but in order to be able to deny their involvement the crews were Egyptians.

In ’82 KiriKiri had been closed, I suppose that the prison was still there.

During the time that I was a member of Lagos Flying Club there was no open military involvement from the USSR and there was no AA at KiriKiri. The oil field were in the hands of American, British and Dutch companies. The Russians must have had an eye for them.

Companies then working the oil fields were Gulf, Mobil, Global Marine (Howard Hughes), Shell-BP and Shell.

Hi Rudy

Thanks for that it brings back a few memories.

I had an interview in London with John Christlieb for the LFC job and flew out to Lagos overnight with Sabena early in 1968, to land at Ikeja on one of those misty mornings when the moisture streams lazily off the tops over the trees around the airport. I had the expected hassle with customs asking for 'Dash' for the underwear in my suitcase. I was rescued by Gus Ashby who had flown in from Kiri Kiri with a Dutchman called Van Toff in a two seater Cessna 150. We flew back to Kiri Kiri with Van Toff standing in the back as I remember it.

Gus Ashby insisted on having a Heineken and then introduced me to the local area from the air in his usual mischievous way by getting airborne again.

Lovely crowd at the club I remember many Germans, Frenchmen etc and I agree that the locals were really nice friendly people and I got very fond of the barman Bassy and his assistant Ekop who were locals.

I think Gerald Impey owned the tripacer and we had the use of a Chipmunk, Cherokeee and three 150 s.

When we wanted to do cross countries I had to visit Nigerian Airforce base at Ikeja which was rather a frightening experience.

The airfield was interesting with concrete blocks of the prison at one end and swampy surroundings full of snakes and large caterpillars and moths/butterflies. The Nigerian army had a couple of Russian AA guns on the perimeter.

I remember the para sailing and the time that an Italian student Bruno went up and the rope broke and he ended up in the ditch with a broken leg and a large number of very disturbed frogs.

One of the members arranged a little safari with the Cherokee and a Cessna. His wife and her brother, who I was teaching to fly, came with us and we flew via Kaduna and Kano to Maidugari and then over the border to the Cameroons and a game reserve called Wazza. We were stuck in Kano for a little while due to the Harmattan dust.

The students at the LFC were not happy with this and complained to the committee. I also got into trouble over the fact that we bought the Cherokeee back to Maidugari to refuel without getting permission and ended up in prison but that was another matter.

Wonderful fun, wonderful people but we had to pack up when Count Von Rosen bought the Minicons [hardened Bolkow Juniors with rocket pods] to Biafra and threatened raids on Lagos.

I never went back to West Africa and ended up with Gulf Aviation – becoming Gulf Air – in Bahrein, coming home eventually to fly for Britannia.

I have just heard sadly that John Chrislieb died a few days ago.

Nice sharing these memories with you

Regards Clive Boarder

What an experience that must have been! Thank you for sharing. I’m not sure if it is bad form to ask about the prison!

Nerves of steel. I guess you were too busy trying to find your way out of your predicament to be nervous. After you were grounded for a week and went through mentally what you did did the horror finally sink in?

Great story. I always enjoy your comments and your insights on “Flying the Friendly skies’ of Europe!

Why didn’t I reply to you, Clive?

Sorry, but Sylvia has posted a link to this post (end June 2023), so maybe you will read it. Better late than never.

You mentioned a few people that I knew very well in those days.

You must have arrived in Nigeria just around, or at least shortly after when I left.

John Christlieb was a wealthy businessman. At the time he lived in a large house near Apapa. His wife, Juliette, was an assistant instructor. there were rumours that their relationship was a bit “shaky”, I don’t know the ins and outs.

John invested money in LFC, very generous and much to the advantage of the members.

Gus Ashby had the habit of drinking a pint of Heineken between lessons, so the last student had to put up with his antics.

Sometimes at the end of the day, he looped the C150. It was not an “Aerobat”, but it seemed to take it in its stride.

Gerald Impey owned the Tri-Pacer 5N-ADH. I had been considering to buy it: at the time the Nigerian currency was no longer interchangeable. One of the members, Ted Alexander, bought a C150 (with Nigerian currency) which he and his wife flew to the UK to sell it there – for £ Sterling..

The UK ARB was still in charge of airworthiness, and the inspector told me that ADH was not going to get an export C of A. There was internal corrosion in the struts and there was no company in Nigeria with the equipment to weld aluminium in aircraft structures.

Gerald lived in a very exclusive estate near the main road to Lagos.

He had uniformed servants. At the end of the road out of Ikeja was a convent and right behind it was a night club, Mogambo.

There was a chimpanzee in a cage. The poor animal was hooked on cigarettes.

Another prominent member was Italian. Giachetti. He lived in a beautiful villa on Victoria Island and owned a Cessna 180, a tail dragger. He only made wheel landings. Nearly all my training before arriving in Nigeria had been on Piper Cubs and Super Cubs. He got a bit nervous when I made a perfect full-stall landing when he allowed me to handle his aircraft (a beauty).

Was HRH Prince William still there? He owned a Twin Comanche, It had a personalised registration, 5N-APW.

There were other members, like Vic Twyford. A very nice group of people and I remember all of them very fondly. Often I was given use of the aircraft to build flying hours, and on weekends I ferried planes back and from Lagos to Kiri Kiri.

I was gone before Von Rosen arrived on the scene. Eventually, Biafra’s Ojukwu had to surrender. To his credit, Gowon was very forgiving to his enemies.

I still remember the slogan:

“To keep Nigeria one

is a task that must be done !”