Confessions of an Old Bold Pilot

Rudy Jakma was kind enough to share with me his story of how he got started in aviation, told in two parts.

Rudy is known to regulars of the website for his fantastic and helpful comments and discussions on the posts. He never fails to add insight and explanations based on his long and varied aviation career.

He retired as a commercial pilot at age 60 but switched to private jets once the French rule prohibiting pilots flying commercially after age 60 was lifted. At 65, he retired for good…but only from flying. At 72 he acquired his coach/tour-bus driving licence to become a tour guide in Dublin and Belfast. He’s now 75 and, in addition to guiding tours, he is also a full-time student at Maynooth University in Ireland.

Here’s the story of how he learned to fly (or almost didn’t get the chance). I hope you enjoy it as much as I have!

Aviation has always had a fascination for me. My first aviation book was a promotion album, issued by a manufacturer of tea and coffee. Tokens had to be collected for the pictures. My mother drank a lot of coffee for that album.

As a teenager I worked at a small aerodrome in my school holidays, helping to assemble and launch advertising banners that would be picked up and towed behind an airplane. The mainstay of the aircraft used for towing was the DH82 Tiger Moth, later replaced with Piper Super Cubs.

I had notions of becoming an artist but was roundly rejected by the art college, lacking talent, I took a job as a clerk in a flying school at the same little aerodrome, Hilversum in the Netherlands (EHHV).

In those days, there were three ways of getting a pilot’s licence: through the Royal Dutch Air Force, getting accepted by the government sponsored KLM cadet scheme (a kind or Eton or Oxford for pilots, a complete immersion in training, including aerobatics and jet time on Hansa Jets, later Citations and including the theory for the ATPL).

There was only one third option: to become a private pilot. In those days, the one and only institute was the National Flying School, operating under the KNVvL, the Royal Dutch Aeronautical Society. This Society controlled every aspect of aviation-as-a-hobby. From model aircraft, ballooning to private flying. The KNVvL did not offer a route to a commercial pilot’s licence.

The flying school at Hilversum co-operated with a few other schools at Teuge, Eelde and Maastricht under the KNVvL banner.

When I worked there, it was possible to take flying lessons. As an employee, at a ridiculously low price I could avail of a slot if a student cancelled at short notice. Although I had a great interest in aviation, I discovered that I was a bit afraid of flying. But I took lessons just so I would know a bit more about what the students were doing. These students assumed, wrongly, that I knew the technical secrets of flying. I didn’t. I wanted to alter that.

The aircraft were Piper L4J Cubs, the military version of the J3. The difference was that they had been built as observer airplanes and had a lot more plexiglass, especially at the back.

The Cub had a 65 HP engine, the fuel tank sat right behind it. The gauge was a spoke on a float. The spoke rose through the filler cap. Precarious in two ways: In case of a crash, the pilot risked being doused with petrol. And if the spoke got only a bit bent, it could get stuck and indicate a decent quantity when the tank was, in fact, just about to run dry. Fortunately, there were lots of flat meadows and the Cub needed only about 100 metres or so to come to a full stop. It did not happen often.

These Cubs did not have any radio nor instruments. They were flown solo from the rear seat. If a student was allowed to solo, they were looking at the empty seat of the instructor who had been sitting there. And often they still leaned sideways to see the instruments past the instructor, whose ghost still occupied the seat in front of them.

Later the school upgraded to the 90 HP PA 18. Still no instruments, no electrics nor a radio. They also were army surplus, with extra plexiglass. But they were soloed from the front seat and the fuel tank was in the wing, the indicator was a cork float in a glass tube.

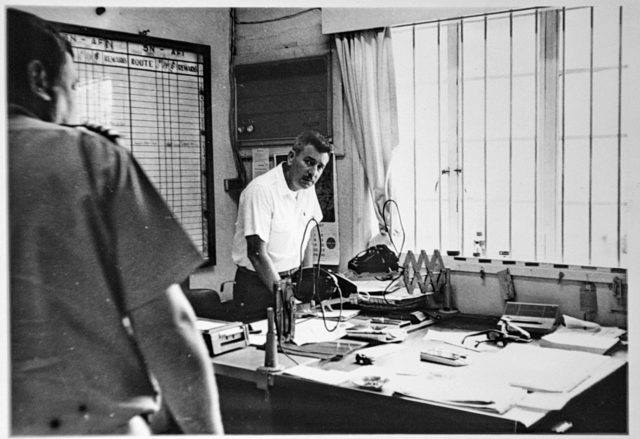

Then I got a job as a flight operations dispatcher in Lagos, Nigeria. I knew nothing about the work, suddenly I had to coordinate and prepare flight plans for aircraft from Cessna 185 float planes, helicopters, Westland Widgeon, Cessna 310, Cessna 411, Beech D18, DC4 and the flagship, a DC-6A. It was a gleaming beauty, not all that long before retired from Japan Air Lines. On the polished aluminium skin it was still possible to make out its former name: “City of Kyoto”.

I had to respond to an HF radio that could burst into life with “Gulf George, Gulf George, Gulf Lima, come in.” – usually in a strong Texas drawl. The company operated aircraft on behalf of Gulf Oil from a strip called Escravos, in the Niger Delta.

I knew nothing about the work, my rudimentary English was what I had learned at school. And I had to deal with many different nationalities, in a language that often was not our common native tongue. We had Americans, but also the Joint Consultants’ Office, we operated a regular service for engineering teams involved with building a hydro power dam in the Niger at Kainji. They were British-French. Another major customer was WACASC, a logistics operation of the combined West African embassies of the United States. This resulted in a mixture of New England, New York, Mid-West and southern American accents. The Africans spoke their own variety and also Pidgin English. It took me a few months to get accustomed.

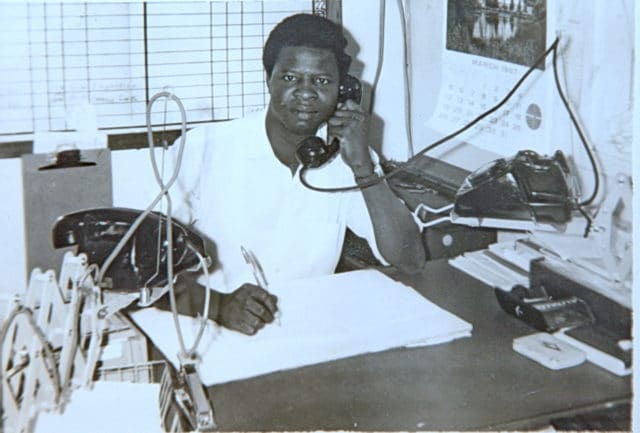

Actually, the Nigerians whom I was supposed to supervise supported me until I finally caught on.

The country was only just emerging from its colonial past. I encountered intelligent, cheerful, hard working, loyal and friendly people. They taught me from the very beginning an important lesson: We tend to classify and judge people as a stereotypes. The difference is in the chances in life that we, born in Europe or the USA, have taken for granted as our automatic birthright, including access to education. Many people in third-world countries never were that lucky. If they were educated, they would have had to fight for it every step of the way.

The year was 1967. I settled in well enough. Eventually.

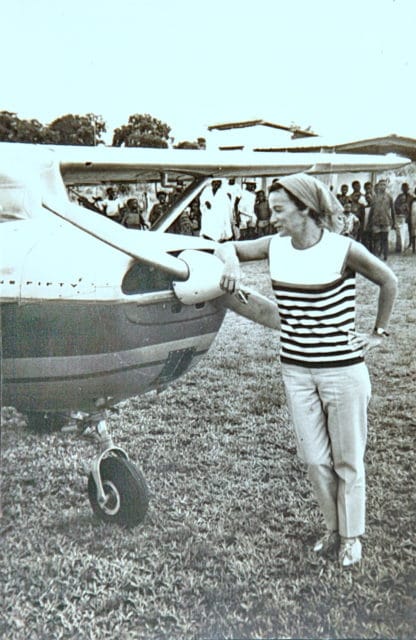

The company that I worked for, Pan African Airlines (Nigeria) Ltd, also had a Cessna dealership called Tropical Aircraft Sales. I don’t think that they sold many but there were a few C150s and a lovely new 172, used for demos and available for rent.

Most private flying was done through the Lagos Flying Club. They had a club house at a strip called KiriKiri, at the coast just at the southern edge of Lagos Airport (DNLL) control zone. KiriKiri was near a prison, deserted during the week (the airstrip, not the prison!). The aircraft were kept at the main airport and ferried over on Saturdays and Sundays. KiriKiri has long since been closed but in those days all private pilots had to learn to use the R/T from day one. A major step up from the Cub, without radio.

Having already soloed, I joined the flying club as soon as I had a chance. To get there by road was quite an adventure. One had to drive in the direction of the port of Apapa, pass a very busy market and try to find the place, which I did after a good many wrong turns. The local people were always courteous and willing to give directions. Just as well, because road signs were virtually absent and the traffic, even then, was absolutely terrible. And in general, so were the roads. Of course, the best, the easiest way to get there was to hitch a lift on one of the aircraft being positioned in the morning from the main airport. Even better if it was flown by a club instructor. After a day at the club in the evening it was the same, in return. KiriKiri had no secure fencing so the aircraft were not normally left over night.

There were quite a few: The club owned a Cherokee 180, another company had a Cherokee 140, a club member had a Cessna 180 tail dragger, there was a Piper Colt, the chairman had a Tri-Pacer, the club used two C150s and there was a third one belonging to Pan African. Sometimes a Twin Comanche would arrive, owned by HRH Prince William of Gloucester.

The club house was a very pleasant place to spend a day. Apart from a bar that served drinks and decent food, there were always some activities. Popular was parasailing: not like what we often see these days at beaches, behind a speedboat. No, here it went behind a car, often a Landrover. A height of over 100 feet was not unusual. At the end of the strip, the car would slow down and stop and the ‘chute would float slowly down for a safe landing. The more brave among us might disconnect and come down like a real parachutist.

It did not always go according to plan. One day, it was the turn of a young teenage girl. There was a bit of wind. She was not very heavy, the breeze was strong enough to keep her up.

The car tried to reverse. Yes, she did descend, but the wind was slightly across the airstrip and she was hanging above a swamp adjoining KiriKiri. A mud bath was not the worst of her worries: it was known that there were snakes of the green and black mamba varieties. Very poisonous, so she had to be left dangling for about 15 minutes until the wind slackened and she came down, none the worse for the experience. Actually she enjoyed the view and did not want to be pulled back in.

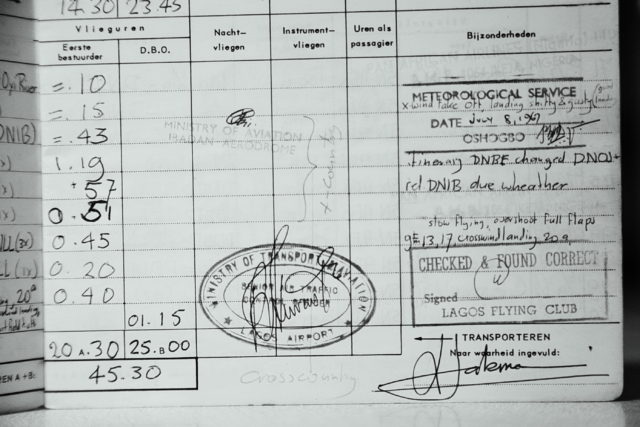

Soon I was able to resume my flying lessons. I still have my very first log book.

Apparently I passed a medical examination with a Dr. Sparrow on April 1st, 1967 and had a 40 minutes’ lesson with Gus Ashby, the club instructor, at KiriKiri. We did a complete review. After all, the last time I had been flying was only two months previously in a totally different environment and in a Piper PA18, PH-JKB, at Hilversum. Now I had to convert to another type, a Cessna 150, 5N-ADD. At the time, I had logged a total of nearly 15 hours of which 3:35 hours solo.

As an instructor, Gus was good. I cannot remember what his day job was, for expatriates were not sent to Nigeria just for a few hours’ flying instruction on week-ends.

His main peculiarity was that it was better to book the morning slots with him.

He used to drink a tankard of Heineken between lessons.

At the end of the day, he might be tempted to do a few loopings. The ‘Aerobat’ had not yet been introduced, but that was no deterrent.

I liked flying but was still a bit skittish when it came to exercises like stalling.

On one of those flights, Gus suddenly decided to do a looping with me.

I was terrified, perhaps rightly so.

The first part seemed to go well, until we reached the top and the Cessna stalled. We were inverted and were showered with sand, wrappers and other dirt that came from the floor before the aircraft came around, completed the loop and righted itself.

The aircraft never was inspected for stress damage nor have I ever heard of anything going wrong with the airframe. Cessna built them well. The owners’ manual started with the sentence: “The beauty of a Cessna is more than skin deep.” I suppose that there was more truth in that statement than had been foreseen when the brochure was written.

Another 3 hours of instruction and I was allowed to solo again. In the tropical heat, we did not wear ties, so no use to bring scissors. Another ritual took place: the pilot who was allowed on his or her first solo was issued with a tin button. It sported the Cessna logo and the slogan “If I can fly, you can fly”. I kept it for many years.

The club used two 150s for instruction and Gus was not the only instructor. Soon I mainly came under the wing of Colin Horsfall.

Colin was a commercial pilot, working for a company called Aero Contractors of Nigeria. A similar operation as Pan African, but they did not have larger machines like the DC-6. They had contracts with another oil exploration company, Shell-BP and ran them from a private strip called Warri.

I had a six day working week, my day off was Saturday. I was single and spent most of these free days at KiriKiri. Sometimes, if it was quiet on a Sunday and an aircraft had not been brought over to the club, I would leave the office to my colleague Adebayo and nip over to KiriKiri. My log book shows a lot of short solo flights of 10-15 minutes.

In June, with a total flying hours of about 33 logged, we made the dual cross-country flight. My logbook entry for June 24th, 1967 tells me that we flew in C150, 5N-AFR. First to Oshogbo, then Ilorin, Oyi Rivers, Ibadan and back to Lagos. A total flying time of 4 hours 55 minutes.

AFR had a third seat and we had another club member with us who was approaching the day of her solo cross-country and had done this trip before. Oyi Rivers was a very small strip, barely visible from the air and the approach had to be made in between the trees. We stopped and a few monks came out to invite us to visit their local leprosy colony nearby, which we turned down. I made a few circuits, two solo. It was real “bush flying” of the kind that perhaps Aussies take for granted. But I do not think that many European student pilots will get that experience.

In my logbook, Colin wrote the entry “solo xc approved”. Now I was raring to go. But the rainy season had started which resulted in weather not really suitable for private pilots. A few dry hours, then a sudden wall of water might move in, in the form of a shower that could instantly reduce visibility to yards. When that happened, a foot of water could easily accumulate. Houses built in lower areas would suddenly be flooded. Our offices were built on a concrete plinth; I found out why.

Another unpleasant consequence was that the flash flooding often dislodged green mambas who sometimes sought refuge in the offices. The black mambas in general were tree dwellers. More poisonous, more aggressive but at least they could avoid humans more easily.

Now the waiting was for a day when the weather would be suitable for my solo cross-country flight.

I reserved 5N-AFR, the 150 that was owned by my employers. The weather had closed in since the dual cross-country flight and remained so for nearly two weeks. The first Saturday came and went, it kept raining.

Then, the next Saturday looked a bit less grey. I drove to the airport. The rain had stopped, there were a few breaks in the clouds. I went to the Met. Office for a weather briefing.

A student must make two landings on different airfields, not being the airport of departure. I had prepared a flight plan from Lagos, to Ibadan, a 45 minutes’ flight north-north-east of Lagos. From there on to Benin City, about 1 hour 50 to the east and back to Lagos.

The VFR maps that I was using came from the U.S. Air Force and showed large areas in white, with remarks like: “No relief data due to incomplete survey” or something to that effect. There were no other maps available at the time. At least, the areas around airports were mapped properly. The maps would have to do.

The forecaster on duty was British. He explained that a large area of bad weather that had covered the south-west of the country was now clearing to the west. He allowed me a look at a large orange radar screen which clearly showed the bad weather as a large blob, now mainly to the west of Lagos. I might still encounter some broken clouds at 1,000 feet but it should clear rapidly. I thanked him, filed my flight plan and went to the ramp to prepare the aircraft.

Note from Sylvia: Rudy will be back next Friday to tell us what happened! In the meantime, feel free to discuss in the comments.

Here it is: Part 2!

I am looking forward to reading more.

But I thought there was bold OR old pilots, but not old AND bold Pilots.

Exactly! Rudy is a special breed.

Thank you Rudy.

I eagerly devour everything Sylvia and Rudy write.

Guys,

The real inspriration of this site is Sylvia.

She is running this blog with a very high degree of professionalism, her articles are well researched, factual and very readable.

I was just unbelievably stupid and was lucky: I got away with it.

Worse: It took me years to realise it.

The tankards of Heineken scared me!

We lived, worked – and flew – in different times then ! Nobody batted an eyelid. And there was never an accident, in spite of the tankards of Heineken.

I’m pleased you’ve given Rudy his own series. I feel that something like that’s been due a while!

Thanks Adrian, but to be honest: I repeat that I am aware that I got away with things that I would actually have to criticize heavily myself.

Times were different.

Fascinating stuff, Rudy.

The Flight Instructor with the Heineken doesn’t surprise me. I suspect he was far from an isolated case, at the time. I know from a ride in a light aircraft that even one drink becomes noticeable as the air thins. Just because you’re feeling ok on the ground doesn’t mean you’ll be alright at altitude. He’s lucky that it didn’t catch up with him.

I look back on my relatively modest experience as a young private pilot and shudder. The Beech Sundowner I flew most often was forgiving and I had sense enough to stay out of bad weather, but there are a lot of choices that I would make differently, had I the chance to redo them. My stick and rudder skills were pretty decent, but my judgment was mediocre. We live and learn; thankfully I lived long enough to learn.