Former 737 MAX Chief Technical Pilot Indicted for Fraud

Yesterday, a federal grand jury indicted Boeing’s former Chief Technical Pilot for fraud, specifically accusing him of deceiving the FAA’s Aircraft Evaluation Group during their evaluation and certification of the 737 MAX and of scheming to defraud Boeing’s US-based airline customers to obtain “tens of millions of dollars” for Boeing.

“Forkner allegedly abused his position of trust by intentionally withholding critical information about MCAS during the FAA evaluation and certification of the 737 MAX and from Boeing’s U.S.‑based airline customers. In doing so, he deprived airlines and pilots from knowing crucial information about an important part of the airplane’s flight controls. Regulators like the FAA serve a vital function to ensure the safety of the flying public. To anyone contemplating criminally impeding a regulator’s function, this indictment makes clear that the Justice Department will pursue the facts and hold you accountable.” –Assistant Attorney General Kenneth A. Polite Jr. of the Justice Department’s Criminal Division

In the US, the federal government must receive an indictment from a grand jury in order to prosecute. A grand jury consists of up to 23 members, of whom 16 must be present to form a quorum. The defendant has an opportunity to challenge evidence but there is no defence attorney in the courtroom and the federal grand jury only has to determine whether there is probable cause for criminal charges. This does not require a unanimous decision; only 12 members need to agree that a federal crime has probably be committed. The standard of proof is much lower than in a criminal crime.

I have read the indictment against the former Chief Technical Pilot Mark A Forkner and the evidence presented against him. Before going into the details, I want to be clear that an indictment is an allegation and the defendant is presumed innocent until proven guilty.

That said, the following is a summary of the sequence of events as related in the indictment.

Boeing began developing and marketing the 737 MAX in June 2011 as a more fuel-efficient version of the Boeing 737 Next Generation (737 NG). The 737 MAX had larger engines which were situated further forward than those on the 737 Next Generation.

The change to the aerodynamics caused the 737 MAX nose to pitch up when turning the aircraft at high speed, in what’s referred to as a “high-speed, wind-up turn”, a corkscrew-like pattern. This is not a manoeuvre that would come up during normal commercial flights. However, Boeing needed to deal with the issue in order to ensure that the aircraft met US airworthiness standards.

This led to the addition of the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) to the 737 MAX design. The MCAS would adjust the nose to pitch down by applying trim inputs to the horizontal stabiliser, the horizontal piece on the tail of the 737. The horizontal stabiliser provides stability to the aircraft: specifically, it tilts up and down in order to stabilise the pitch. On the Boeing 737, the autopilot and other systems, such as the speed trim and the mach trim, can make trim inputs to the horizontal stabiliser via the electric trim switches. The MCAS was installed to make trim inputs in the same way.

Initially, the MCAS was defined as an aircraft part which would only operate at high speed (Mach 0.6-0.8).

The point here is that, as originally conceived, MCAS was designed to deal with a certification issue: in a corkscrew turn at high speeds, the MCAS would pitch the nose down. The scenario would never occur during normal flight.

This was an important point for the FAA’s Aircraft Evaluation Group, which determines the minimum level of pilot training required for a pilot to fly the 737 MAX for US-based airlines.

The Aircraft Evaluation Group was tasked with detailing the differences between the 737 MAX and the 737 NG and to define the “differences-training determination” for the 737 MAX in their Flight Standardization Board Report (FSB Report). US-based airlines would then use the FSB Report as the basis for their pilot training requirements.

The FSB report ranks the nature and extent of the differences range from Level A (least intensive) to Level E. Level B generally requires only computer-based training, which is less expensive for airlines to implement. A training level above Level B is likely to require full-flight simulator training.

Mark A Forkner joined Boeing as a technical pilot as a part of the 737 MAX Flight Technical Team in early 2012. In 2014, he became Boeing’s 737 MAX Chief Technical Pilot.

In that role, Forkner was responsible for providing the FAA with the differences between the 737 Next Generation and the 737 MAX. He also dealt with Boeing’s US-based airline customers and knew that Boeing expected a difference-trainings determination for them that was no greater than Level B. Anything higher would be expensive for the Boeing’s airline customers and at least one of those customers was entitiled to financial compensation (penalties) if the differences training exceeded Level B. He wrote about his concerns in an email in December 2014.

If we lose Level B [it] will be thrown squarely on my shoulders. It was Mark, yes Mark! Who cost Boeing tens of millions of dollars!”

In June 2015, Boeing held a briefing for the FAA Aircraft Evaluation Group. The Boeing representatives told the FAA employees repeatedly that the MCAS would only operate during high-speed, wind-up turns and only if the 737 MAX was flying at high speeds of 0.7-0.8. Forkner was present at the briefing and repeated this information in at least one discussion that day.

On the 16th of August 2016, the FAA Aircraft Evaluation Group issued a provisional Level B differences-training determination for the 737 MAX.

Three months later, Mark Forkner took part in a simulated flight test where he saw MCAS kick in at Mach 0.2. He knew that the FAA was under the impression that this could not happen. He knew that he and his colleagues had told the FAA explicitly that MCAS would only operate at high speeds.

Mach 0.2 is not a high speed: it is the equivalent of around 133 knots or 246 kilometres per hour. To put this into context, the Boeing 737 MAX cruising speed is around 450 knots (Mach 0.79). A normal approach speed is about 140 knots, which meant that MCAS could activate during take-off and landing manoeuvres, which up until now, Forkner (and the FAA) thought was not possible.

That same day, he had an email exchange with another Boeing 737 MAX Flight Technical Pilot.

Forkner: Oh shocker alerT! MCAS is now active down to .2. It’s running rampant in the sim on me. At least that’s what [Boeing simulator engineer] thinks is happening.

Flight Technical Pilot: Oh great, that means we have to update the speed trim description in vol 2

Forkner: so I basically lied to the regulators (unknowingly)

Flight Technical Pilot: It wasn’t a lie, no one told us that was the case.

Forkner may not have known at the time of the briefing but he knew now. He contacted a Boeing senior engineer to clarify the situation. The engineer confirmed that MCAS was no longer limited to operating only during high-speed, wind-up turns.

That same day, Forkner had a meeting with a member of the FAA Aircraft Evaluation Group. The FAA employee asked him about the simulated test flight.

Forkner failed to mention anything to do with the MCAS.

Two days later, the Aircraft Evaluation Group sent Forkner a draft of the forthcoming 737 MAX FSB report. The report determined that that the 737 MAX training level was Level B.

Forkner responded to the report with edits. He did not tell the FAA that MCAS operations were no longer limited. Instead, he recommended that the FAA remove all references to MCAS as unnecessary.

“We agreed not to reference MCAS since its outside [the] normal operating envelope.”

The FAA Aircraft Evaluation Group accepted his recommendation, still confident that MCAS would only operate at high speed wind-up turns and thus was not relevant to normal flight operation.

Every reference to MCAS was deleted from the 7t7 MAX FSB Report. The report was published on the 5th of July 2017.

Forkner emailed a copy of the report to representatives of the major US-based airlines, which highlighted that the FAA Aircraft Evaluation Group had issued a Level B difference-determination.

As MCAS had been removed from the FSB Report, it was equally not mentioned in any of the Boeing manuals and pilot-training materials. There was no way for the airlines to know it existed.

Boeing received the 737 MAX sales that they were hoping for but under false pretences: if the truth about MCAS had come out, the difference-determination would have almost certainly been higher than Level B.

In July 2018, Forkner left Boeing. A few months later, on the 29th of October 2018, Lion Air flight 610 crashed shortly after takeoff and it quickly became clear that MCAS was operating in the moments before the crash.

The FAA Aircraft Evaluation Group realised that MCAS was no longer limited to high-speed wind-up turns and that it could operate at speeds much, much lower than Mach 0.7.

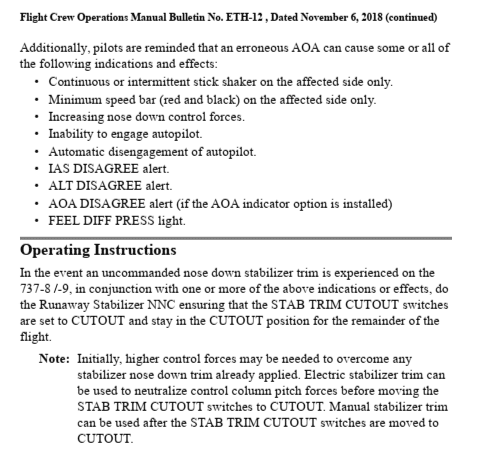

Boeing issued a press release blaming the faulty AOA sensor and the pilots. They also released an urgent bulletin to all 737-8 and 737-9 pilots.

The FAA Aircraft Evaluation Group began to review and evaluate the actual operation of the MCAS but it must be said that the indictment does not mention the FAA’s vocal support of Boeing, despite the growing realisation that they’d been lied to. Nor does it mention Boeing’s initial blaming of the faulty AOA sensor and the pilots. Boeing also released an urgent bulletin for all 737-8 and 737-9 pilots.

On the 10th of March, 2019, Ethiopian Airlines flight 302 crashed near Ejere shortly after take off. Again, it quickly became clear that MCAS was operating in the moments before the crash.

The indictment glosses over the FAA response:

Shortly after that crash, all 737 MAX airplanes were grounded in the United States.

Actually, initially the FAA announced their support for Boeing. In response, aviation authorities grounded the aircraft and banned it from their airspace. Boeing stuck to their guns, arguing that MCAS was “under the hood” and that pilots did not need to understand or even know about it for the safe operation of the aircraft. The two accidents, said Boeing, were not linked.

It was four days after the crash and the Boeing 737 MAX had effectively been grounded around the world when the FAA announced that they were in possession of new evidence linking the two crashes. On the 14th of March, the FAA released an emergency order of prohibition against the operation of Boeing Company Model 737-8 and 737-9 by US certificated operators.

But going back to the indictment, the charges are focused on Forkner’s part in the deception, as it was Forkner, in his role of Chief Technical Pilot, who was responsible for provising the FAA with “true, accurate and complete information about the differences between the 737 MAX and the 737 NG. From the point when Forkner received the draft report, he’s accused of having actively deceived the FAA Aircraft Evaluation Group about the status of MCAS.

Forkner is charged with two counts of fraud involving aircraft parts in interstate commerce and four counts of wire fraud

The interstate wire fraud, by the way, are four invoices that Forkner “knowingly transmitted and caused to be transmitted” to the two US-based airline customers for the Boeing 737 MAX.

If he is convicted, Forkner faces a maximum penalty of 20 years in prison for each of the four counts of wire fraud and 10 years in prison for each of the two counts of fraud involving aircraft parts in interstate commerce.

“There is no excusing those who deceive safety regulators for the sake of personal gain or commercial expediency. Our office works continuously to help keep the skies safe for flying and protect the traveling public from needless danger. Today’s charges demonstrate our unwavering commitment to working with our law enforcement and prosecutorial partners to hold responsible those who put lives at risk.” –Inspector General Eric J. Soskin of the U.S. Department of Transportation

You can download the Forkner Indictment (PDF) from the justice.gov site.

The Chicago field offices of the FBI and the DOT OIG (Department of Transportatoin Office of Inspector General) are investigating. The Criminal Division’s Fraud Section and trial attorneys from the US Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Texas are prosecuting.

Based on the details presented in yesterday’s indictment, it seems that as Chief Technical Pilot, Folkner had very specific responsibilities to the FAA and to the airlines, much as we would regard the captain as responsible for his aircraft and the passengers within. Based on the evidence represented in the indictment, it is alleged that not only did he neglect to share the details after he knew that MCAS would operate under normal flight conditions, he actively encouraged the FAA to remove all references from the report in order to protect the Level B determination.

However, even if every allegation is proven, the man could not and did not act alone. We’ve looked at systemic issues at airlines and maintenance organisations before and it seems very clear that there was a company culture issue at Boeing which led to this whole tragedy. I will be very disappointed if the Department of Justice does not continue to investigate Boeing.

Sylvia, I don’t fully understand the “four invoices” sent to 2 US carriers. What was covered in those invoices — products/services not provided or?

Wire fraud is a federal crime which is a Class C felony, more commonly used against telemarketing frauds and internet scams. The four invoices were for payments for the Boeing 737 MAX. The point is (I think) that they were electronically sent by (and on behalf of?) Forkner in his role of Chief Technical Pilot which allows for the four counts of federal wire fraud. The question will be whether the prosecution can prove that Forkner was part of a scheme to defraud the airlines. It seems to me they are using this charge on the basis of failure to disclose with the intent to defraud.

Thanks, Sylvia. I got it now. Your depth of research is amazing. :)

I saw the news stories about the indictment and was curious why they’d indicted a pilot and not the executives. This makes a lot more sense now. I find it interesting that the change caught Boeing’s Chief Technical Pilot by surprise; this doesn’t speak highly, to me, about Boeing’s internal communication processes. But it makes sense that once he knew about the behavior change in the MCAS system, he had an affirmative duty to let the FAA know, and he lied (by omission) to them, no doubt banking on the probability that the lie wouldn’t matter enough to be worth jeopardizing tens of millions of dollars in revenue. He was, unfortunately, tragically mistaken in that gamble.

Though I understand why crime victims are not identified in general, I was amused by the Justice Department’s identification of the airlines as simply “Airline 1” and “Airline 2” in the indictment. There aren’t that many US operators of the 737MAX, and even fewer headquartered in Texas, so it takes no great act of deduction to figure out who they are.

Agreed, well said.

Assuming of course that the charges will hold – Sylvia quite correctly reminds her readers that Forkner, even if formally indicted, will be innocent in the eye of the law until proven guilty – the seriousness of this case is spreading like an overturned full ink bottle.

Tammy is quite right when she (I assume Tammy is female?) asserts that Boeing’s internal communication was quite severely lacking. And it also appears that if and when it did take place, it did not lead to any serious head scratching and calls for meetings to put the heads together and come to a solution.

Or if that did happen, it suggests that the findings were covered up, wiped under the carpet.

My experience in aviation tells me that taking serious action would potentially not be “jeopardizing tens of millions of dollars in revenue.” Considering the size of the market and the number of aircraft, as well as airlines worldwide involved, coming up with a real solution would probably have involved hundreds of millions of dollars.

In all likelihood it would have meant expensive modifications, or at least a far more extensive MCAS with additional duplication of sensors and developing and installing fail-safe systems, as well as additional crew training. Boeing is big enough so that it could have shrugged off even “tens of millions of dollars”, but the delay that all this would have caused alone would have meant that the airlines would have postponed introduction of the – MAX and been clamoring for compensation.

Of course, the covid-19 pandemic was a cynical godsent to the industry because it stopped airline operations nearly dead in its tracks. The grounded aircraft were not needed after all, at least not until resumption of flights.

As it so turned out, the gamble that Boeing took backfired massively. It cost not only a very large of money, but worse, the lives of many people. And put a dent, a gaping hole actually, in the reputation of Boeing as a trustworthy manufacturer of some of the best, most successful airliners ever.

But the FAA does not come out smelling of roses either. They allowed Boeing to pull the wool over their eyes. Was the FAA caught napping, or was the agency complicit, hoping that the problem could be solved whilst keeping the truth “under the radar”? We will probably never know. Forkner, guilty or not, seems to be the convenient fall guy.

Agree. It looks like a terrible, seemingly unethical, business decision (avoiding short term delays vs risk of massive reputation damage, expense and loss of life). The management structures and people have real questions to answer, including in court

Critically, however, it was implemented extremely poorly.

Even with a single non-redundant sensor, and MCAS undocumented, a hard limit on the total amount of MCAS trim would have avoided this disaster. The reset on every manual trim, allowing the build up of small MCAS trim into movement all the way to the hard stop, was what doomed these planes. The programmers and engineers who implemented it like that also carry a large share of guilt.

The US legal system has some interesting quirks, for sure. One of the quirks is concurring legislation: any state can prosecute a crime (e.g. fraud) committed in that state in the state legal system according to that state’s laws; but to prosecute a crime in the federal court system, it needs to fit a federal law, and that often happens when more than one state is involved.

That means that Forkner lying to the FAA in Seattle or Portland is not a federal crime and couldn’t be indicted by a federal Grand Jury; but “interstate commerce” and “wire fraud” are covered by federal legislation and can therefore be prosecuted according to federal laws. This is why these charges seem to not be a good fit for the crime.

The US system is (almost) unique in the world in that Grand Juriy decisions are required to accuse someone of a serious crime. In other countries, typically the prosecutor makes that decision on their own. However, unlike other countries, the District Attorney is an elected position, so their competence and impartiality may be less trusted than elsewhere?

US law also necessitates a federal Grand Jury for organized crime or government corruption. The Grand Jury might have had to consider whether FAA officials were involved, or whether more people at Boeing acted together; and that may be why the first indictment in the 787 Max complex comes from the federal Grand Jury and not a state prosecutor.

It’ll be interesting to find out if Forkner has already been interviewed by the FBI. He has the power to make a plea deal and reduce his sentence if he can testify against other people responsible for the MCAS cover-up. It is possible that, with Forkner’s testimony, more indictments could follow.

Actually, this is not the first time the MCAS deception has been prosecuted. From a Department of Justice press release, January 7th 2021, at https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/boeing-charged-737-max-fraud-conspiracy-and-agrees-pay-over-25-billion :

That means the last two paragraphs in my previous comment probably don’t apply.

Both of your comments are really helpful in clearing this up. Thank you!

Sylvia already said it: Colin and Mendel added some very helpful information. And it is revealing to read about the rather convoluted legal system in the USA. No wonder that in the aftermath of the attempted overthrow of the US government on January 6th so few have been convicted of so monstrous a crime. Maybe more will follow, but… no, let us stick with aviation and leave politics out of it !

So “hundreds of millions” for the change to maintain ‘Level B’ certification, or “thousands of millions and hundreds of dead people” for sweeping it under the rug.

Yep, looks like McDonnell Douglas really did take over Boeing, not the other way around.

And also somewhat grimly amusing: No penalties for the executives who refused to fund the development of a new airframe, and signed off on the whole MCAS debacle – after all, “It was Mark! Yes, Mark!”.

Unfortunately for him, I don’t think he has US$2.5 billion of someone else’s money to pay off the Feds with. The phrase ‘thrown under bus’ springs immediately to mind. J.

Sylvia, you have collected quite a few posts on the 737 MAX issues. Maybe it’s time to add a new category to the site?

If the MCAS system was supposed to be programmed for speeds in excess of mach 0.6-0.7, who was responsible for not correctly coding this parameter in the programming? And, as a follow-up, when this guy saw that MCAS was activating at 0.2; why didn’t he have those designers correct the problem?

Personally, I think that a lot more people from Boeing need to end up in prison beyond Forkner.

New news: Blooomberg investigator Peter Robison has published “Flying Blind: The 737 Max Tragedy and the Fall of Boeing”, which (from the review and interview) damns the entire culture going back decades (to the combining with McDonnell-Douglas and the accession of a CEO trained by a notorious cost-cutter).

Review (may be paywalled): https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/01/books/review/peter-robison-flying-blind-boeing-737.html

Extensive author interview: https://www.npr.org/2021/11/29/1059784424/flying-blind-author-says-boeing-put-profit-ahead-of-safety-with-the-737-max

Thanks for this. I’ll take a look

I just watched “Downfall: The Case Against Boeing”, a 90-minute documentary new on netflix that explains the issues around the 737 MAX in a very accessible way. Much of it is narrated by Andy Pasztor of the Wall Street Journal, but there are many other voices as well, most prominently Peter DeFazio who headed the congressional investigation.

The movie starts by going into the LionAir 610 crash from the perspective of the wife of the pilot, documenting the pilot blaming after the crash, and then explaining what MCAS is and how it caused the two crashes, with the technical details simplified for a general audience. (Sylvia’s posts on this blog go into much more detail – why is there still no 737MAX category on the blog?)

From minute 38 on, they go into Boeing company culture, how it went downhill after the McDonnell-Douglas merger, financial pressure, and Airbus competition.

From minute 59 on the documentary shows why Boeing decided to modify the 737, why that necessitated MCAS, why Boeing concealed it, and why that was dangerous.

The conclusion of the movie lays out the consequenced that followed, and I got the impression that everyone got off lightly. Boeing claims the 737 MAX is now safe.

I found the film well made, showing footage I had not yet seen; it simplifies a lot, but as far as I can tell, does so responsibly. For me, it’s been a good recap with some new angles; for people not familiar with the issues, it provides a thorough overview of how and why Boeing designed, marketed and produced an unsafe aircraft.

In other news:

Boeing’s stock price is holding at 2017 levels, half of its all-time high and double its post-MAX low.

Forstner had 2 of the 6 charges dropped because MCAS is software and not an “airplane part”; his trial is set to start in March.

I will look for that documentary, it sounds interesting. Did you feel our look at the Boeing company culture was in line with what they presented?

This question should be on the latest post! :)

It’s on my list. My plan is to make a category (I was a bit stuck as to what to call it, but 737MAX means Ethiopian can be in the same place) and also collect all the pieces into a book (sticking to all the technical issues but explaining the detail a bit more as I won’t be cramped for space). But my world is a mess right now and it’s not going to happen just yet.