Sharing a Runway: Fed Ex vs Southwest at Austin

On Monday, two commercial aircraft had a near-miss on the runway at Austin-Bergstrom International Airport in Texas.

The airport at Austin has two parallel concrete runways which run north-to-south: 18L/36R and 18R/36L. The numbers 18 and 36 signify 180° and 360° and L/R is left or right, as seen when flying towards the active runway.

Earlier that morning, Fed Ex flight FX1432 departed Memphis, Tennessee. The aircraft was a Boeing 767-300, registration N297FE, on a scheduled cargo flight. As the Boeing approached Austin, the visibility was poor with dense fog.

Here are some photographs taken at Austin International that morning.

This is what it looked like this morning at AUS. Lots of go arounds. pic.twitter.com/ywMEZnTovP

— Brandon 🛬 (@onshortfinal) February 5, 2023

I’ve made a transcript of the interactions with Austin Tower. You can listen along with the audio here: https://s.broadcastify.com/audio/KAUS-Twr-2023-02-04-1230z.mp3

Note that runways are always given as individual numbers (one eight left) and the calls are preceded/ended with the station being called and the station calling. I’ve simplified this after the first calls to make the interactions a little easier to read.

FedEx 1432: Austin Tower, Fed Ex 1432 heavy, passing 5.4 for the CAT III ILS one eight left.

This is the Fed Ex flight inbound to Austin. The flight crew refers to themselves as “heavy” to highlight that it is a large aircraft (with a maximum take-off weight of over 136,000 kilos or 300,000 pounds ) and requires more separation from other aircraft to avoid wake turbulence. As an example, in 2017, a business jet was flipped after flying through the wake of an Airbus 380 passing a thousand feet above..

A category III approach is a precision instrument approach that allows flights to continue despite poor visibility. These approaches have a lower minimum decision height than a visual approach. They also specify a minimum runway visual range.

Austin Tower: Fed Ex 1432 heavy, Austin Tower. One eight left RVR: touchdown 1400, midpoint 600, rollout, 1800. 18 left, cleared to land.

The Runway Visual Range (RVR) is a measurement of how much of the runway you can see from the three key positions. The runway has three sensors installed, one at each threshold and one in the centre, in order to give the horizontal visibility for the positions, so that the flight crew know the true visibility for the full landing or take off. For a category III a approach, the runway visual range must be not less than 700 feet at the touchdown point and 500 feet at the midpoint. The decision height, when the aircraft must have the runway in sight, should be no lower than 100 feet.

FedEx 1432: Cleared to land one eight left.

At the same time, Southwest Airlines flight WN-708 was ready to depart from Austin with a destination of Cancun, Mexico. The aircraft was a Boeing 737-700, registration N7827A.

Southwest 708: Tower, Southwest 708. We’re short of one eight left and we’re ready.

Southwest 708 has taxied to the runway and is stopped there (holding short), waiting for permission to enter the runway for their departure.

Tower: Southwest 708, Austin Tower. Runway 18 left RVR: touchdown 1,200, midpoint 600, rollout 1,600. Fly heading 170, runway 18 left, cleared for takeoff. Traffic three miles final is a heavy 767.

Southwest 708: OK, fly heading 170 and cleared for take off 18 left. Copy the traffic.

So now we have Fed Ex cleared to land and Southwest cleared to take-off. Staggered permissions are common and both planes know about each other; however, in the poor visibility, it is also just a little bit tight.

Although this has been trimmed from the recording, there is about ten seconds of silence on the frequency while FedEx continues its approach and Southwest lines up on the runway ready to depart.

FedEx 1432: Tower, confirm Fedex 1432 heavy is cleared to land on 18 left.

Tower: That is affirmative. 18 left, you are cleared to land. Traffic departing prior to your arrival is a 737.

FedEx 1432: Roger.

Moments later, the controller becomes concerned that Southwest is still on the runway.

Tower: Southwest 708, confirm on a roll?

He’s asking if Southwest has started its take-off roll, accelerating on the runway to take off.

Southwest 708: Rolling now.

At this point, Fed Ex is coming in to land and close enough to see Southwest, which is still on the runway. At the point when the Pilot Flying initiated the go-around, they were 150 feet above ground level and 1,000 feet short of the runway threshold (300 metres )

Unidentified voice (since confirmed to have been FedEx 1432): Southwest abort!

Same voice: Fedex is on the go.

The flight crew on the Fed Ex flight has aborted their landing and in the process of a go-around. The phrasing “on the go” is usually used by ATC and in this instance, I think that the flight crew meant to signal to Southwest that the Boeing 767 was overhead.

Tower: Southwest 708, Roger. You can turn right when able.

Tower is responding to Southwest, presumably thinking that Southwest has called that they are aborting. It seems to me that there’s an odd nonchalance here (when able) and it’s not clear whether the instruction is for the aircraft lifting off (in which case he should give a heading) or for the aircraft on the ground (in which case, the aircraft needs to expedite getting off the runway and out of the way of the landing aircraft, there’s no need to give a direction).

Southwest 708: Negative.

I think this is in response to the (Fed Ex) call to abort the take off. Once the aircraft has exceeded the V1 speed on the takeoff roll, it is not safe to reject the takeoff. They must continue. But it’s not clear here whether the Southwest flight crew understand the situation. They are still at risk of a collision: the fast-climbing Southwest aircraft could easy fly into Fed Ex, which is passing above them and still needs to gain airspeed.

FlightRadar24 estimate that the Fed Ex Boeing 767 was 75 feet above mean sea level as it crossed over the Southwest Boeing 737, which was at four feet above ground level. Just to put that in perspective, the Boeing 737 tail is 35 feet high.

The more I look at the above statement, the less I like it. See Jacob’s comment below for a breakdown of the relative heights and altitudes.

Tower: Fedex 1432, climb and maintain 3,000. Then you can turn left, heading 080.

Fedex 1432: left turn 080, 3000.

Tower: Southwest 708, you can turn left heading 170.

Southwest 708: 170.

Here, the controller is separating the traffic, sending Fedex northeast and the Southwest to the south.

Tower: Fedex 1432, turn left heading 360, contact approach on 125.32

Fedex 1432: 25.32, left 360.

The Fed Ex pilot is very calm and professional. I think I’d be shouting at the controller to ensure that he realised what the hell just happened.

At this point, Fed Ex changed frequencies in order to rejoin the pattern and fly another approach.

Tower: Southwest 708, you can contact departures.

And then it was quiet until Fed Ex lined up for the second attempt, which was uneventful. A few minutes later, the following exchange took place.

Fedex 1432: Fedex 1432 is exiting Lima

The Fed Ex flight has landed safely and is exiting the runway at taxiway L.

Tower: Roger. Report clear of the runway. You can join [taxiway] Bravo and contact ground on .9

Fedex 1432: We’ll join Bravo. Ground .9 … and Fedex 1432 heavy is clear of the runway.

Tower: Roger. Sir, you have our apologies. We appreciate your professionalism.

Fedex 1432: Thank you.

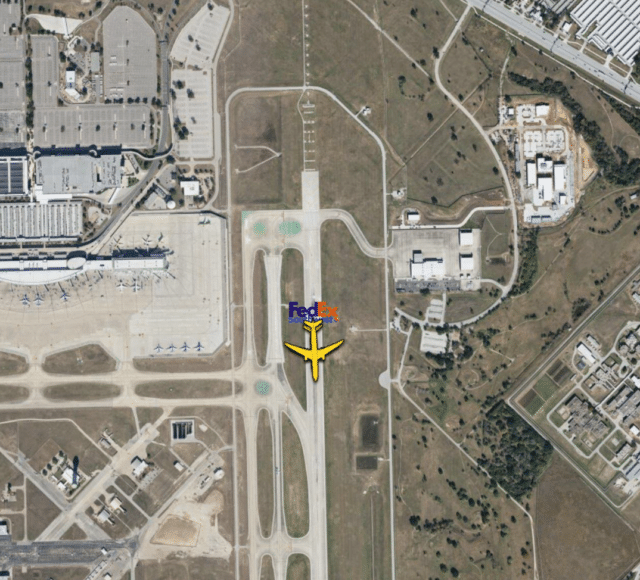

Flightradar24 has published a video using the ADS-B data to show the relative positions of the aircraft.

The NTSB is investigating an incident involving a Southwest 737 and FedEx 767 that occurred today in Austin. Initial ADS-B data show the landing 767 overflying the departing 737. We are processing granular data now. https://t.co/twHCydm5ixhttps://t.co/wZ3Z0xKJem pic.twitter.com/nkKVjshXmf

— Flightradar24 (@flightradar24) February 5, 2023

The FAA and the NTSB are investigating. The chair of the NTSB said in an interview that it was “fairly clear that the aircraft came within very close proximity of each other and we believe it’s less than 100 feet.” She compared the incident to the near miss at John F Kennedy last month, when an American Airlines aircraft crossed the runway ahead of a Delta Air Lines flight. The crisis was averted because JFK has Airport Surface Detection Equipment (ASDE-X), which uses radar, multi-lateration sensors and satellite technology to track the position of aircraft and vehicles in and around the airport. Austin does not have this surveillance system.

“Air traffic controllers in Austin could see the FedEx plane coming in, but couldn’t actually see where the Southwest plane was in relation to the FedEx plane because the Southwest plane was on the ground,” Homendy explained. “Had they had that technology … they would have been able to see both the FedEx flight and the Southwest flight.”

That said, it seems odd that Fed Ex Boeing was cleared to land before Southwest had taxied onto the runway. Southwest needed some time to line up and there was no sense of urgency until the Fed Ex flight crew called to confirm that they were right to expect 18L to be clear. Once you take the poor visibility into account, this seems like a very poor decision on behalf of air traffic control, made worse by the lack of ground radar at Austin.

I’m looking forward to the final report.

How exactly did you calculate that FDX was 75′ AGL? This MUST be a calculated value, because the ADS-B data (from FlightRadar24 and other sources) is a pressure altitude—neither an MSL altitude nor an AGL altitude.

I used Equation 7 from here (https://aviation.stackexchange.com/a/95292/) to find the indicated altitude “h” given the known pressure altitude (75 ft or 22.86 m) and the contemporary altimeter setting (30.43 “Hg or 103050 Pa). The altimeter-indicated altitude would have been 165 m (540 ft) MSL, or only 50 feet above TDZE!

I then used Equations 8 and 9 to find the “true” altitude of 157 m (515 ft) MSL—barely 23 (that’s TWENTY THREE) feet above TDZE. Yikes.

Bear in mind this is all based on ADS-B/Mode C altitude data which itself has a resolution of only 25 feet, so we’re talking about a greater than 100% margin of error in the numbers. With any luck the NTSB will have access to FDX’s flight data recorder, which (I hope?) includes radar altimeter data. But as the NTSB chair said, it certainly seems like less than 100′ vertically.

Well, if we have the pressure altitude of both aircraft, and they’re set to the same altimeter setting (which may be a bad assumption) then I’d expect we could subtract one from the other and get the vertical separation?

Aside to Sylvia: You have 2 separate paragraphs with the same runway information.

The FedEx pilot is EXTREMELY calm and professional. I’m sure he realizes the controller will catch hell from the FAA and anything he says is just a bad reflection on him,

He’s far, far more levelheaded than I! Kudos to the FedEx pilot.

It’s not quite that simple. ADS-B transponders have the capability to include an “on ground” flag, which it seems FR24 and most other sites interpret as “0” AMSL altitude (see the granular track data for SWA from https://www.flightradar24.com/blog/ntsb-faa-investigating-fedex-southwest-close-call-in-austin/). Obviously that is not truly zero because Austin is approx. 500′ AMSL at ground level! This can quickly complicate a true comparison in time. For example in the SWA data, FR24 shows them at “0” from the start of the file until 12:40:34. Then there are three hits of “25” (a pressure altitude), then one hit of “0” (is that a pressure altitude or “on ground”?) at 12:40:49, then another “25” and finally “100,” “200,” “300,” “350.” This while the FDX data has them quickly going from a pressure altitude of “75” at 12:40:31 to “525” at 12:40:49.

Actually, yes, this is clearly pressure altitude and I’ve pointed people to read your breakdown instead. Thanks.

Thanks for that, Jacob. My apologies, that definitely should have said AMSL not AGL and I’ve corrected it above. Flightradar24 cite 75 feet as the altitude (clarifying that it is the barometric value above mean sea level calibrated as standard atmospheric pressure). I’ve also made the attribution to Flightradar24 clearer. Next time, however, I’ll ask you to do that math! Yikes, indeed.

A question from a novice. Should the controller, after having made that mistake, stepped aside for someone else to take over? He would be trying to do his job with a head full of thoughts and distractions. Is this possible or are there limited resources in the tower. Is it more safe to let him continue as he knows the skies around him?

Generally speaking, yes, if at all possible, a controller would hand over to another controller, after a serious incident, for exactly that reason. However, the radio seems to be pretty quiet and I’m not sure what may have happened in this case.

All of the money we’re hemorrhaging on our proxy war, and our major airports go without advanced sensing systems.

This was mighty close. I respect the flight crew who kept their cam very much. I’m glad they are getting some recognition.

45 major US airports have ASDE-X or ASSC surveillance systems, according to Wikipedia.

In Austin, there might have been 400 passengers at risk. The OHCHR has recorded over 7000 civilians killed in Ukraine so far, among them well over 400 children.

Keep calm when comparing aviation incidents and wars.

For CAT III approaches, isn’t there supposed to be a protected area where large metal objects (like aeroplanes) aren’t allowed because of the distorting effects they have on the ILS signal? Hence distinct VFR/CAT I/II holding points vs CAT III holding points.

I’m surprised that South West was allowed past the CAT III holding point once FedEx was established on the approach, or a least when it was that close.

There is, but it’s not a monolithic area: there is one for the glide slope and one for the localizer. For this runway the glide slope critical area is on the other side of the runway from where Southwest was holding short, and it does not extend onto the runway pavement. When Southwest taxied “into position” on the approach end of the runway they were not within either critical area. As they rolled down the runway they entered the localizer critical area—and this IS allowable, even for a CAT III approach, provided they would have been clear of the area by the time the arrival was on a half-mile final.

In this particular case the arrival was just about on top of Southwest, so obviously the localizer area was NOT clear by the time the arrival was on a half-mile final… but in the general case the critical area is not so sacrosanct as to prevent other arrivals and departures on the runway.

With reference to – “The flight crew on the Fed Ex flight has aborted their landing and in the process of a go-around. The phrasing “on the go” is meant to signal that the aircraft is still over the runway”

The phrase “on the go” is an americanism for “going around.” This is the correct terminology. Nothing to do with indicating that “the aircraft is still over the runway.”

It happens a great deal. At 2’30” another aircraft states “ready to go.” The correct call is “ready for departure.” A another point at which confusion could be sparked.

The Tenerife air disaster was the beginning of creating standardised phraseology and pilots are not adhering to the norm. This will lead to another massive cock-up if unprofessional pilots continue with lax r/t discipline.

As for the incident itself. The fact that one aircraft was not yet on the runway and cleared to enter whilst another was a 3 miles (all in thick fog) should have led to one of the pilots challenging the tower. Simply to ask if a landing clearance was confirmed was totally inadequate.

This incident was totally avoidable and a bit of simple 3D thinking on the part of the crews could easily have saved the day.

I agree with you regarding pilots not adhering to standardised phraseology, especially in the US.

However, my understanding is that “on the go” is specifically used by ATC in the US, to refer to an aircraft that is going around. I’ve not previously seen references to pilots announcing that they were “on the go” to signify their intent to go around. That said, I haven’t flown in America, so I’m happy to be corrected.

You are right Sylvia – we seem to be agreeing. It was Fedex who said “on the go.” He should have said “Fedex 1432 is going around.” The phrase does not imply that he is still over the runway as you indicated.

Agreed — that was my interpretation as to why the flight crew used that phrasing, to try to alert Southwest that they were in their overhead. I’ve made it clearer.

Carl — there may or may not have been someone immediately available to take over this controller’s slot. I get the impression that US ATC isn’t as understaffed as it was for many years after PATCO struck and Reagan fired the lot of them, but I wouldn’t assume there would be standbys — especially as this is not yet a hugely busy airport. (Wikipedia says <600 movements/day; plans a few years ago were to grow from 11 million passengers/year capacity to 30 million, but not how stretched out those plans are since COVID.)

Sylvia: looks like a typo in “(with a maximum take-off weight of over 13,600 kilos or 300,000 pounds)” — 136,000 kilos?

Ouch, yes. I clearly was a bit too quick to release this one. Thanks.

I’m looking at the times shown by my mp3 player and wondering whether it was edited at all or whether ATC wasn’t keeping up with the FedEx

* FedEx says “5.4” at :07 of the recording

* ATC clears SW for takeoff at 0:53

* ATC says “traffic 3 miles” at 0:54

* ATC calls SW to confirm on a roll: 1:21

* SW says “rolling now”: 1:24

* FedEx says “SW abort”: 1:27

How fast would FedEx have been going before starting to flare? If they could actually see SW in visibility of 1/4 mile, they’d covered >5 miles in 1:20, which is >195 knots — possibly reasonable if https://community.infiniteflight.com/t/boeing-767-300-tutorial/22880 is correct that landing speed is 145-150 knots. (They shouldn’t have been planning to land long, as the FedEx facility at AUS would have been behind them before they crossed the landing threshold.)

Was SW slow in starting their takeoff roll, despite having been warned of traffic? I wonder whether they were still lining up when the tower called them. (I’ve never checked the number of seconds between crossing the hold line and actually starting to roll when I’ve been a passenger, but I remember everything from position-and-hold (common at BOS, probably to let someone land on a close parallel) to “The captain says we’re going to fast-taxi and takeoff NOW before regional ATC loses sight of the inbound (at Ketchikan).)

This does look mostly like a controller being outright wrong in calculations in their head, but they could also have been caught by imprecision after making the mistaken assumption that everything would happen in the time specified in some training manual. AUS isn’t so busy on the average that there should have been a need to push planes into the air as quickly as possible.

The New York Times has published a discussion of this mess, including notes that the controller who erred was on an overtime shift and that the only other person in the tower was a “supervisor” who was handling ground traffic (so immediately relieving the tower controller (as suggested above) wasn’t possible). The article also says the FAA claims the airport wasn’t understaffed (possibly technically true given the low traffic levels) and has a link to an interim report. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/11/business/air-traffic-control-austin-airport-fedex-southwest.html

The preliminary report is at https://data.ntsb.gov/carol-repgen/api/Aviation/ReportMain/GenerateNewestReport/106680/pdf . These are easy to find on the NTSB search (CAROL) if you have the aircraft registration, which Sylvia provided.

Based on the times given in the report, the recording you referenced in your previous post appears to have been edited.