Land Like a Crow Part 1

The entire world seemed to be watching when LOT airlines flight LO16 landed wheels up at Warsaw Airport in 2011. I wrote about it at the time, impressed with the smooth landing:

The captain of the flight, Tadeusz Wrona, was the subject of much admiration as a result. His last name means crow in Polish, leading to this lovely popular proverb in Poland:

Lataj jak orzeł, ląduj jak Wrona.

Fly like an eagle, land like a Crow.

I stopped looking for updates after a year or so, assuming that the resulting investigation was not that interesting. So I was surprised to see the final report suddenly appear a couple of months ago, six years after the incident took place. There’s a lot to this and full credit to the State Commission on Aircraft Accidents Investigation in Warsaw who took the time to really delve into the human factors at play in this incident. You can find the whole report online: B767-300ER November 1 2011 Warsaw Chopin Airport Runway 33

On the 1st of November 2011, LOT Polish Airlines flight 16 was a Boeing 767-300 ER aircraft registration SP-LPC scheduled for a flight from Newark Liberty Airport in New Jersey to Warsaw, Poland. It underwent a standard pre-departure check and pre-flight check at Newark. The pre-departure check was done by a ground engineer and did not include a cockpit check. The pre-flight check was by the flight crew: the captain did the exterior walk-around and the first officer checked the cockpit. No failures or irregularities were found. They started the engines at 03:58 LMT (local Polish time which is used throughout the report; this is the timezone the flight crew were effectively ‘on’) and departed normally twenty minutes later.

The flight crew were retracting the landing gear and flaps when the centre hydraulic system failed. The centre hydraulic system is necessary for extending the landing gear.

The crew contacted the operations centre via ACARS at 04:39 to tell them that the hydraulic system had failed. They asked for an analysis of the situation and suggestions as to whether to continue the flight or turn back to Newark. The Operations Centre suggested that they continue the flight and follow the recommendations in the Quick Reference Handbook.

Realistically, the flight was in no danger and the flight crew agreed that the Boeing 767 could safely continue to Warsaw. Once there, if the hydraulic extension wasn’t possible, they would use the alternate system to extend the landing gear.

This was probably a long and stressful flight for the crew, who effectively had nothing they could do but wait. The Operations Centre did have some options: this would have been a good time for a risk assessment and consider possible escalations of the situation, so that they would be ready in an emergency. However, there was no procedure in place for this kind of forward planning so, as the aircraft continued on its way to Warsaw, the Operations Centre did nothing.

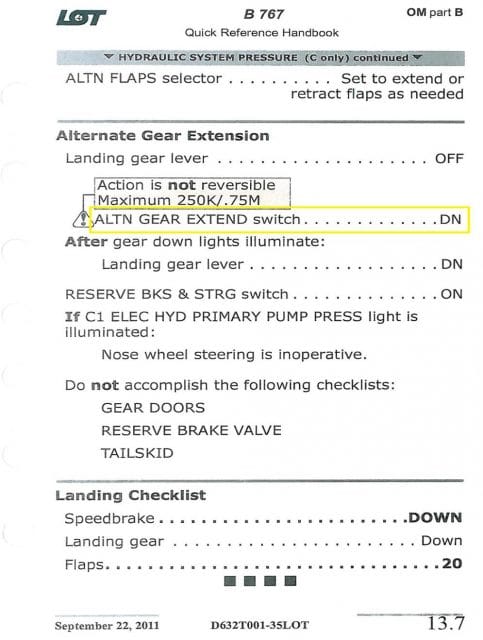

As they approached Warsaw, the captain was the Pilot Flying and the first officer was the Pilot Monitoring. They followed the HYDRAULIC SYSTEM PRESSURE checklist which included the checklist for ALTN GEAR EXTEND, using the alternate system. However, when they did so, nothing happened.

They checked the Quick Reference Handbook and made sure that that they had followed the landing gear extension procedure for the alternate system correctly. They had, but it didn’t help. The landing gear did not extend.

The HYDRAULIC SYSTEM PRESSURE did not have any instructions for what the crew should do if the alternate system failed. There was also no reference to the relevant checklists later in the manual (Non-Normal Checklists, Landing Gear). If it had, they would have found the GEAR DISAGREE checklist which dealt with what to do if there was a partial failure in extending the landing gear. There was still no advice for if all three legs failed to extend. There was no checklist for ALL GEAR UP LANDING. The flight crew were on their own.

The flight crew declared an emergency and requested support from the operations centre, asking for consultation with a ground maintenance personnel and a Boeing 767 instructor pilot. Operations had eight hours notice that there was a problem during which they could easily have found expert help in case it was needed but when it came to it, they hadn’t prepared for such an eventuality. They found an instructor pilot to offer advice to the crew within a few minutes but it took over twenty minutes to get a ground engineer in touch. The ground radio station designated for engineering staff to speak to flight crew wasn’t working and the engineer had to drive to the Operations Centre. Twenty minutes may not seem like a lot but the flight crew were under a ticking clock as they burned away their fuel in a holding pattern above Warsaw.

Meanwhile, two Polish Air Force F-16s flew alongside the Boeing 767 and confirmed that the landing gear was still in the retracted position but the tail skid was enabled. The flight crew attempted to extend the landing gear ‘in a gravitational way,’ that is, manually opening the doors and hoping that that the landing gear will effectively fall out and into place. It didn’t work.

The flight crew informed the Senior Cabin Crew Member that there was no choice: they were going to have to land on the belly of the aircraft and evacuate immediately onto the runway.

The Senior Cabin Crew Member should have briefed each member of the cabin crew individually. Instead, he chose a few members of the cabin crew and asked them to speak to the others and then they would brief the passengers. Then, the cabin crew had some difficulties in finding the right pages in the Passenger Briefing and Evacuation Commands Booklet. When they started instructing the passengers, they noticed that some of them were struggling to concentrate and were only able to understand simple commands. As a result, the cabin crew members started to use their own words, to simplify the explanation from the booklet.

Instead of waiting for the Senior Cabin Crew Member, three of the crew began to shout BRACE when they looked out the windows and saw that the aircraft was not far above the ground. The Senior Cabin Crew Member then called out the BRACE command using the public address system. As a result, the passengers had difficulty hearing and not sure what was going on.

The Boeing 767 touched down on runway 33 at 13:39 local time. As it skidded along the runway, sparks flew from the right engine. The captain had given the instruction to evacuate the passengers immediately when the aircraft came to a rest, without waiting for an order from the cockpit.

The touch down, as you can see from the video, was perfectly executed. So much so, that the Senior Cabin Crew Member, expecting a hard landing, thought that perhaps they had landed normally. He wasn’t sure that an evacuation was necessary after all, so he didn’t immediately open the doors. With no order from the cockpit, he simply wasn’t sure.

Meanwhile, the cabin crew at the rear of the cabin evacuated immediately. In the end, everyone was off the aircraft just two minutes after touchdown but once the passengers had been evacuated, there was further confusion as to what to do.

The cabin crew were not given any instructions and passengers waited by the aircraft for about 15 minutes. Two of the cabin crew members took the passengers in a bus to a terminal but had no idea what to do next. The rest of the crew, some of them without shoes, stayed by the aircraft for an hour and a half, wondering where the two missing cabin crew members had disappeared to.

Even once everyone had been safely delivered to the terminal, the problems weren’t over. Warsaw Chopin Airport had no way to clear the runway of the disabled Boeing 767. The airport was closed to air traffic for over 29 hours. In the end, they used a harness and airbags designed for a 737.

When the investigation team arrived at the airport, the first thing they did was inspect the cockpit and cabin. And that’s when they found that on the P-6 panel, a circuit breaker was popped out.

The investigators pushed the circuit breaker back in and pulled the lever for the alternate landing gear extension system. The landing gear extended and locked. This meant that the entire problem with the alternate extension system was the popped out cirbuilt breaker. Even after the emergency landing on the belly of the plane, the alternate landing gear extension worked just fine once the circuit breaker was in place.

Next week, we’ll look into the deeper details of the accident report and the human factors that could lead to the crew deliberately making a gear-up landing in a functional aircraft.

(Source – SCAAI)

##Edit: Part 2 is now here!

Surprisingly, for an airline that had a reputation as being professional, this article seems to demonstrate the opposite.

The organisation, reading this article, seems to have fallen apart. And this was nothing like a sudden, major disaster.

Surely, having had eight hours (!!) to prepare for the eventuality of a 767 possibly having to make a gear-up landing, the operational people seem to have sat on their fat bottoms until the final moment when decisions HAD to be made.

Until the end of Syliva’s first part, it seemed as if the cockpit crew had done a good enough job. The decision to brief the decision of evacuation up to the cabin crew, having told them only to do this “at their own initiative” flies in the face of all established emergency procedures. A “belly-up” landing may not go exactly as expected, the cockpit crew should determine when it is safe to open the doors and if necessary add specifics e.g. left doors only.

The final nail in the coffin appears to be the missed cb.

But the check lists seem to have contained lacunes.

When a new type is introduced in an airline, a committee consisting of experts like chief pilot, ops manager, fleet captain, instructor pilots, engineering staff, etc., will scrutinise the checklists, including of course abnormal and emergency procedures as provided by the manufacturer.

They will consult and use the aircraft manuals and from all the relevant material distill the version that is to be used in the cockpit.

This will then be submitted to the relevant Civil Aviation Authorities who, in turn, will scrutinise and approve – or may demand amendments before approval.

This elaborate method will ensure that the checklists and flight operational material will conform to the company standard operational procedures AND will conform to the manufacturers’ procedures and recommendations, with the CAA as arbiter and referee. Who will have sent their own experts to the manufacturers’ base to ensure that they will work at the same level as the airline staff. Aviation authorities also employ highly experienced pilots who can, and will, test fly a new type to be certified.

From what I read here there seem to have been unexplained gaps in the check lists.

But maybe it will all be revealed next week.

Well, not to a truly satisfying conclusion but yes, there’s a few issues there that desperately needed updating. Mainly, I was impressed that they didn’t just leave it at the popped breaker without further analysis.

I’m surprised there isn’t a gear system in place that could be turned by a manual crank handle that would allow the crew to manually crank the wheels down, in the event of these system failures.

Mike,

The Cessna 310 I used to fly did have a crank handle, it was operated by a sort of bicycle chain. I never had to use it in real life. :-)

We tried it once, in the hanger with the aircraft on jacks for maintenance.

It was a surprisingly heavy and time-consuming job, and that without airlfow making it even more difficult.

Unfortunately, such a simple system won’t do in a large, complicated aircraft with multiple hydraulic systems.

I’ve only skimmed the 200+ pages of the final report, but I noticed that in addition to the crew failing to notice the popped breaker (not surprising given where it was), the report says there was a Boeing-recommended fix (increasing the radius of a bend in the hydraulic line) that hadn’t been done; had it been done, the primary gear system probably wouldn’t have failed. This sounds like an automobile “recall”, which (at least in the US) is usually very well publicized by the manufacturer to owners even if it’s not something spectacular that the news media report on it. Taking one’s car to an authorized repair shop is voluntary for private drivers; does the Polish CAA not require public carriers to make sure that updates recommended by the manufacturer have been done? (I haven’t dug into the report far enough to be sure whether the shield Boeing provided to prevent breakers in later 767’s from being accidentally kicked open was also available as a recommended fix at that time.)

I was … unimpressed … by Boeing blowing off most of the suggestions for improvement; I get that checklists for emergencies need to be compact, but the changes suggested were small. Is this a typical response? Rudy: from your commercial experience, do the suggested changes seem excessive?

I’ll get to this but it wasn’t a recommended update, just an available one. :)

Aircraft manufacturers can – and do – classify maintenance directives according to the urgency.

They can, for instance, be ‘mandatory’.

This is something the aircraft industry is very reluctant to impose because it can ground an entire fleet of the same type of aircraft – worldwide.

This is tricky because it is bad for business.

I am not sure of the time, but there were a few issues with the baggage doors of the DC10 that ultimately caused the crash of a Turkish Airlines DC10. Which was worse for business because ultimately it led to the end of McDonnell Douglas as an independent aircraft manufacturer.

The directives can be recommended, or stipulate a time limit or relate it to a certain number of ‘cycles’.

Some modifications, as Sylvia says, are not mandatory but optional.

No, it is not a straightforward matter at all.

I believe that KLM was one of the few airlines that modified their DC10 fleet with larger vents that could equalise pressure between the cabin and the hold more efficiently, thus reducing the risk of the cabin floor collapsing in the event of a baggage door opening in flight.

The hydraulic lines all ran under the floor, A collapse caused the loss of ALL hydraulics, including to the flight controls.

Sylvia, wasn’t that the cause of the Sioux City crash?

Just to illustrate how complex these maintenance issues can be:

I worked for a short time for a small air taxi and cargo company flying F27 and FH227. They bought another FH227 from a Swedish company. Because they already operated an FH227, previously acquired in France, the aviation authorities had approved the French maintenance schedule. The Swedes had a maintenance cycle that was not synchronous. Nothing wrong with either, but it took months for the paperwork to be sorted out and the extra maintenance to be carried out to put the new arrival on the “same sheet”. Not to mention an extra heavy financial set-back.

For a similar reason, believe it or not, when Concorde was still in operation, the British and French Concordes were not automatically interchangeable. Some modifications mandated by the authorities in one country were not required in the other.

How difficult is it to “manually open the doors” (I assume for the landing gear) for the crew? Is there a way to do this remotely?

They are big and heavy and meant to be opened with hydraulics. In an aircraft that size, if the hydraulic and the electric extension fail, it’s difficult and unlikely.

Gotcha-thank you!