Final Report: Convair Crash at Wonderboom, Pretoria

Last year, I wrote about the fatal Convair Crash at Pretoria which took place in June 2018. The final report came out in August which gives a lot more information than we had at the time.

Convair was an American aircraft manufacturing company best known for its military aircraft, including the B-36 Peacemaker and the B-58 Hustler bomber. They designed a Convair twin engine airliner in 1947 which led to the development of the CV-340, which could seat 44 passengers. The CV-340 replaced United Airlines DC-3 and KLM operated the aircraft from 1953-1963. Many CV340 aircraft were converted to the CV-440, which included an additional two rows of seats, improved soundproofing and a higher maximum weight.

The Convair 340/440 registration ZS-BRV was owned by Rovos Rail who had retired it from service in 2009. Rovos Rail later arranged for it to be sold (some sources say they donated it) to the Dutch aviation museum Luchtvaart Themapark Aviodrome located in Lelystad.

The museum arranged for ZS-BRV to be restored and painted in February 2017 before being flown to the Netherlands. In December, it was branded with the colours of Martin’s Air Charter, a Dutch cargo airline which had operated Convairs. The last logged flight of the aircraft was 22 February 2018.

In April, the Museum representatives came to South Africa for an inspection of the Convair 340/440 and its documentation. The Convair was serviced and inspected, ready to be ferried to the Netherlands, on the 6th July 2018. As a part of the maintenance, the manifold pressure gauge (with a dual indicator for the left and right engine) was removed and repaired. The right engine valve on the gauge had carbon deposits and maintenance staff cleaned both the left and right engine valves before reassembling the manifold pressure gauge and refitting it.

On the 10th of July, four days after the maintenance was completed, Rovos Rail and Aviodrome signed the sale agreement for the Convair. The aircraft was refuelled with 2,100 litres of low lead (LL) 100 octane fuel.

The flight crew, two Australian pilots, both had valid Australian licences. The captain, who was Pilot Flying, held an Australian ATL, Commercial Licence and Private Licence and had 18,240 flight hours, with 63 on type (in 2016 and 2017). However, his validation from the South African Civil Aviation Authority was for a Private Pilot Licence under visual flight rules (VFR) only.

The first officer, who was Pilot Monitoring, held an Australian Private Licence which had been validated by the South African Civil Aviation Authority in 2016, two years before the accident. In 2017 he acquired the Convair 340/440 rating. His total hours and the experience with the Convair could not be confirmed as his logbook could not be found (it might have been in the aircraft).

Neither was actually authorised to operate a South African registered Convair 340/440 and neither had applied for a rating for the Convair 340/440. Both of their South African licences were limited to single engine aircraft.

They had last flown the Convair 17 months before the accident, which means that even if they had been authorised to fly the Convair in South Africa, they would not have complied with the 12-month competency check.

Now lack of paperwork doesn’t necessarily mean a lack of ability to fly but it is clearly bypassing systems meant to provide the public with reassurance that their flight is safe. It also shows a lack of attention to detail and a lack of care when it comes to regulations.

The third person in the cockpit, who was not listed as crew, was the licensed aircraft maintenance engineer who was responsible for the maintenance of the aircraft. Although technically a passenger, he took part in the flight from the jump seat. His assistant was to fly in the cabin with the rest of the passengers.

The engineer was the only person in South Africa who was licensed to work on the aircraft. There was no documentation to show when the engineer had last undergone a recurrent training/competency check as required by South African Aviation Regulations. The maintenance organisation where he worked was not able to show any training records for the engineer.

The aircraft itself did not have a flight data recorder nor a cockpit voice recorder installed and it was not required to do so. However, there was a GoPro video system installed which recorded some of the aspects and parameters of the flight as well as the voices inside the cockpit.

On that day, the flight crew filed their VFR flight plan with Johannesburg Briefing. They planned to fly to Pilanesberg Aerodrome and then back to Wonderboom. Neither the flight crew nor ATC seem to have been aware of the Notice to Airmen (NOTAM) declaring Pilanesberg Aerodrome’s runway closed to fixed-wing aircraft as it was undergoing maintenance.

Including the engineer and his assistant, there were 17 passengers booked on the flight: 12 South Africans, 1 Australian, 1 Zimbabwean and 3 from the Netherlands. All of the passengers were asked to sign an indemnity before the flight.

The weather was good: scattered clouds at 3,500 feet and a breeze blowing 270° at four knots.

The engineer connected the tug and towed the aircraft for start-up and taxi. The passengers were invited to board the aircraft.

Once the flight crew had started the right engine, the engineer’s assistant disconnected the external ground power unit and boarded the aircraft. He took a seat in the cabin with the rest of the passengers while the flight crew completed their run up checks. The flight crew requested taxi and take-off from runway 29.

As they began their taxi, the Pilot Flying complained about the stiffness of the rudder. He also commented that the left engine’s auto-feather light was not illuminating when tested. The engineer, sitting in the jump seat, agreed, saying that the light bulb was inoperative.

A review of the GoPro cameras fitted onto the aircraft showed that the Convair repeatedly drifted to the left and then came back to the centreline.

ATC cleared the aircraft for departure. The Convair entered the runway and began to accelerate.

As it reached 50 knots, the Pilot Monitoring noticed that the left engine manifold pressure was low and said so. It was still possible to abort the flight as they had not yet reached V1 — the speed at which they were committed to continue with the take-off — but the decision had to be taken quickly. A few seconds later, the Pilot Monitoring called V1, thus committing the flight crew to continuing.

The aircraft rotated. As it lifted off the runway, flames appeared on the top front side of the left engine cowling and the exhaust area. The aircraft climbed away at a rate of 600 to 700 feet per minute while passengers in the cabin filmed the flames licking the engine.

The assistant engineer who was sitting in the cabin came to the flight deck to alert his boss in the jump seat that the left engine was on fire. Then he quickly returned to his seat so that he could record the smoke and flames for troubleshooting once they were back on the ground. Looking out the window, he was surprised to see that the they were no longer climbing, in fact the aircraft was losing height.

The flight crew broadcast a MAYDAY call.

ZS-BRV:Mayday! Zulu Sierra Bravo Romeo Victor engine fire left hand engine

TOWER: Bravo Romeo Victor, report on the right downwind runway two nine (siren in the background)

TOWER: Bravo Romeo Victor, report your intentions

ZS-BRV: Yeah, standby

The final report is a bit confusing on this score.

The ATC confirmed to the investigators that the left engine had caught fire and that the crew had broadcasted a ‘MAYDAY’, however when the crew broadcasted ‘MAYDAY’ they did not indicate what the nature of their emergency was. This statement was confirmed by the recordings of the cockpit GoPro camera.

Now, I’m sorry, but in the transcript as included in the accident report, they very clearly state that they have an engine fire in the left hand engine. I can just imagine ATC responding saying, “Yes, but what is the emergency?”

I think rather the issue was that the flight crew did not say what they intended to do, which meant that ATC was not in a great position to prepare and support.

In any event, the controller activated the crash alarm immediately and prioritised the flight for landing, on the assumption that the Convair would return to the airfield.

TOWER: Bravo Romeo Victor, runway two, correction runway two four is available for landing

ZS-BRV: Ehhh…negative. We on downwind standby

TOWER: Bravo Romeo Victor, circuit is clear, you can fly a tight base report final approach runway two nine, number one.

The engine continued to burn. In the cockpit, the left engine’s RPM indicator fluctuated and eventually the fire master caution light came on, accompanied by an audible warning sound. The engineer handed the Pilot Monitoring the quick reference handbook, presumably so that the flight crew could follow the procedures for an emergency in-flight fire.

The Convair was losing altitude quickly.

The checklist for an engine fire reads as follows:

- Feather the propeller

- Pull the appropriate fluid shut-off “T” handle

- Close the heat source valves of the burning nacelle with the emergency heat valve disconnect switch

- Place the cowl doors switch of the burning nacelle to the CLOSE position v. Place the fuel shut-off valve switch of failed engine to the CLOSE position

- Place boost pump switch of the inoperative engine to OFF position

- With fire extinguisher selector on main, operate the appropriate fire switch. The main circuit breaker (CB) supply out light on the fire control panel should come on

- If the fire persists, place the fire extinguisher selector to reserve and operate the appropriate fire switch

The engineer in the jump seat handed the Quick Reference Manual to the Pilot Monitoring, but he never opened it.

ZS-BRV: Bravo Romeo Victor we gonna try and track for a right base two nine.

The Pilot Flying initiated a right turn to return to the airfield but the engine fire intensified. The left wing rear spar and the left aileron system were damaged by the heat.

He pulled the control wheel to the right, complaining that they had lost aileron control, and requesting rudder input from the Pilot Monitoring as he struggled to control the aircraft. He then asked the Pilot Monitoring whether the gears were retracted, no longer sure of the aircraft’s configuration.

What he didn’t do was identify which engine was burning and attempt to extinguish it. Although the assistant engineer had clearly come forward and warned them about the left engine, the flight crew appeared not to know which engine was on fire.

Multi-engine crew are trained to shut down down the engine immediately if they suspect a fire in the engine. But for some reason, the flight crew didn’t do this. They never discussed the checklist. The propeller was never feathered, the fuel was never cut off, the fire extinguishing system was never activated. Instead, the engine was simply left to burn.

The engineer was operating the engine controls and overhead switches while the aircraft turned right again onto base leg, still losing height. The flight crew watched the engineer, seemingly unsure what to do.

On the ground, bystanders watched melted metal debris falling from the left engine exhaust as the Convair continued to lose altitude.

The fire in the left-wing rear spar had melted the aileron cables. They lost all aileron control. The Pilot Flying’s stress can be seen even in the written transcription through his unintentional radio calls to ATC.

ZS-BRV: Click click…rudder. Give me right rudder

ZS-BRV: I’m trying…give me right rudder…help me with it

TOWER: Bravo Romeo Victor, runway two nine cleared to land surface wind is calm

ZS-BRV: Cleared to land runway two nine, Bravo Romeo Victor

ZS-BRV: I can’t, give me rudder…give me rudder

TOWER: Bravo Romeo Victor position?

-END OF RECORDING-

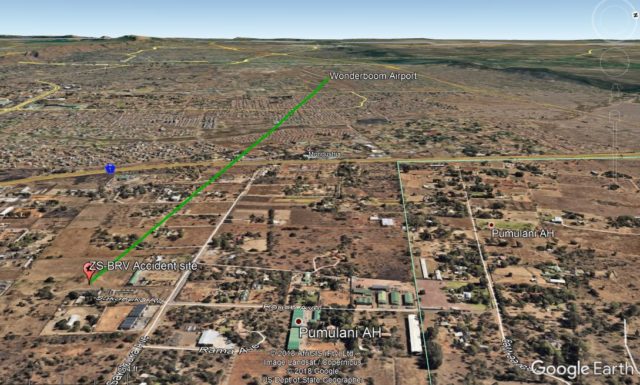

About six kilometres east of the airfield, the Pilot Flying lost control of the aircraft as it descended left wing low in a slight roll, made worse by the partial power in the left engine.

The Convair flew into electrical power lines running along the street at 30 metres (100 feet). As the aircraft continued to descend, the left wing clipped a tree and then struck two commercial vehicles parked outside of the factory. The aircraft crashed through the centre of the factory, losing the left wing and the right engine.

The remaining wreckage was found a few metres further, where the Convair had fallen to pieces with the final impact in a vacant lot behind the factory.

Emergency services rushed to the scene. The passengers were quickly transported to local hospitals but the rescue units could not get the crew out of the cockpit. The Jaws of Life were needed to free the trapped flight crew who were immediately airlifted to a hospital in Johannesburg. The engineer, who had been sat in the jump seat, was dead.

The crew, two passengers and four people on the ground were seriously injured and required urgent medical care. The others, including another four people on the ground, suffered minor lacerations but no serious injuries.

The day after the accident, the investigation team noted a beeping sound coming from the aft section of the aircraft, which had separated from the fuselage. It was the emergency locator transmitter (ELT).

I think there’s quite enough here for a discussion of what went wrong so I’m going to leave you to it and next week I’ll finish going through the report, which will shed some light on why the fire started in the first place.

Edit: Part 2: Misdiagnosis

This seems to have been an avoidable accident. The engine fire probably could, and should, have been contained if it had not been for the trule appalling lack of professionalism demonstrated by the crew. Who signed off for these cowboys to operate an aircraft they were very obviously not nearly qualified to operate? Someone must have given the authorisation. These pilots were limited to single engine, VFR only?

Any pilot, even half trained on multi-engined aircraft should know that the immediate action should have been to – identify failing engine, – feather propeller, – fuel shut-off, activate fire extinguisher (wait until it can be established that the fire is out, if necessary activate extinguisher 2), and – alert ATC. These things are basic and apply broadly to ANY multi-engine aircraft. With the engine feathered, the aircraft would have been able to climb, or at least maintain altitude.

Sorry I have to come out very hard against the crew: their attiude and lack of professionalism borders on the criminal. My verdict: manslaughter !

This seems to have been an avoidable accident. The engine fire probably could, and should, have been contained if it had not been for the trule appalling lack of professionalism demonstrated by the crew. Who signed off for these cowboys to operate an aircraft they were very obviously not nearly qualified to operate? Someone must have given the authorisation. These pilots were limited to single engine, VFR only?

Any pilot, even half trained on multi-engined aircraft should know that the immediate action should have been to – identify failing engine, – feather propeller, – fuel shut-off, – activate fire extinguisher (wait until it can be established that the fire is out, – if necessary activate extinguisher 2), and – alert ATC. These things are basic and apply broadly to ANY multi-engine aircraft. With the engine feathered, the aircraft would have been able to climb, or at least maintain altitude.

Sorry I have to come out very hard against the crew: their attiude and lack of professionalism borders on the criminal. My verdict: manslaughter !

I don’t know why my comment was published twice, but BTW the Martinair Convairs (Insofar as I seem to remember the company operated two of them) were actually Convair 580s: They had been converted to Allison turboprops. I have flown in one of them – as a passenger.

I’m not a pilot, but from reading the report, the pilots are entirely out of their depth, totally unaware of what to do, and frankly seemed to hope that they could just ignore the fire as long as they landed quickly.

Reality, however, caught up with them, with the unfeathered prop of the stopped engine draining power, and the unextinguished fire (still being fed fuel and oxygen) burning away they control linkages.

What isn’t clear is whether their decision to fly this plane without the required training was due to ignorance of the risks, an arrogant assumption that flying a multi-engine plane couldn’t be that much harder than a single engine plane, or application of external pressure.

Whatever the background, this “accident” reeks of criminal negligence, and as noted in the first comment, manslaughter.

It’s hard to disagree with Rudy on this accident. The pilots seemed to mitigate their lack of experience and qualification in this aircraft by having an engineer on board. What they should have done (instead of looking at him juggle the throttles) is exactly what Rudy said. Fly the aeroplane, Identify the engine, feather, shut off fuel/electrics, fire the extinguishers. And if they had time to complete the QRF, shut all the cowl flaps. Then talk to ATC and the passengers. It all happened quickly, but with the prop feathered and retardant activated more time could have been gained to do the rest. I heard the pilot and co-pilot were in induced comas afterward. I hope they are recovering. My sympathy is with them and all those families involved in this tragic event.

Manslaughter maybe — but who should be charged? I keep hearing how flying in the rest of the world is much more regulated than in the US, but this sounds like somebody let a couple of grossly-underexperienced people fly a plane with passengers; I’d say (while not knowing anything about South-Africa–specific laws) that the papers signed by the passengers are irrelevant given the carelessness of whoever was supposed to be managing the aircraft. ISTM especially bitter that the unqualified cowboys piloting the Convair may pull through, while the competent who was flying third seat and who tried to get the cowboys to take action, is dead.

Meanwhile, I’m watching for more info on a similar mess locally: 2 days ago a demo B-17 crashed ~100 miles from here (Boston), with seven of thirteen dead. No word yet on what went wrong, beyond a problem near takeoff that led to a crash landing at the airport; maybe in a year there will be a report for Sylvia to point us to.

These men were experienced pilots (the captain was a retired Qantas A380 senior check captain, the co-pilot was A380 check-and-training captain) with over 37000 hours between them. They flew various historical multiengine planes at HARS aviation museum.

Very experienced and the Captain was a friend. Sadly he passed from his injuries.

Ok, the obvious thing is that the “engine feathered” light being inoperable might mean they thought the engine was feathered when it wasn’t.

The PM clearly didn’t act on the book, a prompt like “call out the checklist, please” might have helped here. It’s kind of hard to get a pucture of what was happening in the cockpit, with both pilots fighting the controls and the engineer doing what?, they seemed to have been underhanded?

CRM would have required someone to take charge of the checklist and another crew member to execute it.

I suspect that Sylvia’s post next week will be very revealing. But the sheer lack of anything approaching airmanship here is appalling, especially given the stated hours of the Captain – not sure where the figures for the PM came from. As to the lack of valid licenses – the mind boggles. One also wonders at the museum’s involvement here – presumably, these were the pilots due to fly to the Netherlands a few days later?

A few comments here:

I know of a few other instances where pilots who normally operate in a highly regulated airline environment abandon all or a lot of their professionalism when asked to fly a historic aircraft, or an aircraft that is expected to be less demanding. A similar case happened in the ‘nineties, when a Dutch DC3, operated by the Dutch Dakota Association, crashed with the loss of life of all on board. The crew were experienced airline pilots. They were fully current and qualified on the DC3. But an engine failed and the feathering pump malfunctioned. The crew did try to feather the propeller of the failed engine which promptly unfeathered again, and again.

Both pilots were so engrossed in this problem that they forgot to keep control of the aircraft which stalled and crashed on tidal sandbanks off the Dutch coast. The crash was unavoidable, but it would have been totally survivable if the crew had made a controlled ditching. The tide was out and lifeboats were on the scene very quickly.

Pilots of this caliber, in the Convair case, should have known better than to break all rules and behave in the manner as described by Sylvia. Not qualified, not current. And yes, one wonders what the involvement of the museum was. Were they aware that the crew, in spite of their high qualifications in general, were in no way qualified to operate this particular aircraft? There may not have been any qualified instructors available, but that is no excuse. In a case like that, before taking passengers on board, the absolute minimum should have entailed a test flight and some touch-and-goes.

Crew coordination seemed to have been virtually non-existent.

Very strange, unbelievable actually, when I read the comments of “hat-eater”.

Disclaimers in general have no standing in law, this has come up several times in my flying career.

And so, yes I still am of the opinion that this sad story must fall under the category of “criminal negligence”. Which may well mean “manslaugter”. And if the museum staff were aware of the lack of qualifications to operate this particular flight, then guilt should rest with them too.

I just learned that a historic B-17 crashed at Bradley International, Connecticut, on October 2nd, with engine problems on the ground that may have developed into a failed engine in the air later. The NTSB is investigating.

It’s uncanny how that crash of a historic plane passenger flight almost coincides with the article that Sylvia had queued up here.

What a shame. I guess that it goes to show that specific training and currency are important, even if you have a lot of other experience. I would assume that with 18,000+ hours and an ATL, the pilot flying had experience in planes far more complex than the Convair, but he obviously did not take that Convair seriously enough that he investigated the pull to the left adequately, before leaving the ground. He didn’t follow procedures when things went wrong and ended up in a very bad crash.

My genuine, calibrate SWAG on this one is that the pilot probably felt that the Convair was much simpler than other aircraft he was accustomed to flying and didn’t consider it much of a challenge. He was a Transport Rated pilot, but not for an aircraft registered in South Africa. The FO was only a private pilot, even in Australia but was typed for the 340?!?! That’s strange, but possible. I can’t imagine any reason for him to do this. I’m a Private Pilot and, yes, I could pay to be typed in something much more complex than the Beechcraft I’m most experienced in, but how can someone remain current in such a situation? Unless you have money to burn or very unusual circumstances, the answer is that you probably cannot.

So, at best, the flight was not legal and a bad idea. Beyond that, the Pilot Flying continued a takeoff, in spite of engine problems which manifested themselves before V1. Then when they had an inflight fire he didn’t follow procedures, in spite of being handed the Quick Reference Manual?

This was certainly preventable, avoidable and there’s a dead engineer. Four completely innocent people on the ground were badly injured and lots of property damage. I hope this guy lost his Aussie ATL, because I sure wouldn’t want to ride with him.

My only question here is this: why did it take so long to complete the circuit to return to the airfield. Yes, I’m aware that they didn’t have sufficient power to turn too tightly as this could’ve resulted in a stall. Perhaps due to them trying continue to fly the plane resulted in them getting so far away from the airfield. If it was me with an engine on fire I would’ve returned to the airfield as quickly as possible!

Obviously incompetent to fly this aircraft and criminally reckless to take passengers. A license to fly highly automated modern aircraft does not in any way qualify the pilots to fly one of these old piston relics. The pilots did not know the drills. Truly amazing that any survived. Thanks to the building for dissipating a lot of energy. An historic B-17 crashed in Illinois, USA a while back after engine fire. Pilots pancake-landed it in a corn field and all walked away. Plane was totally burned. These two pilots really messed up by even starting the engines, much less trying to fly this bird. While faulty maintenance may have caused the fire, the pilots caused the crash.

Eustacius makes a good point. Flying an old historic bird requires, if not a different skillset, certainly additonal skills to what is needed to operate a modern airliner with all “bells and whistles”. In the latter, automation not only takes over some work from the pilots in many ways, but there are also sophisticated systems to alert the pilots of malfunctions and failures. Operating them may be quite different in many ways.

The older aircraft may seem simple, but they are also more demanding when it comes to the basic skills.

I know of a pilot who was up for command in an airline. He had been flying modern types and could not handle system differences in the older model that he was going to be flying as a captain.Old fashioned VOR-DME instead of FMS, no “glass cockpit”, that sort of differences.

And in the case of the Convair crash this may well have played a role. When it came to skills required to work out what was going wrong, without the aid of alerting panels that would present the failures with the required sequence of dealing with them, they “lost the plot”.

In the old days we just had to get on with it. I flew with a cargo airline that had a mix of various models of the Fokker F27. Some had been bought from Air France who had used them for mail deliveries. These aircraft had been equipped with special autopilot systems and the crews were allowed to go to cat 3 minima with special training and dispensation, albeit only in France.

When these aircraft were passed on to the cargo airline they were getting old and if an autopilot failed there were no more parts available, they had been a special AF adaptation. So we did a lot of hand flying and nearly all of it at night. I made the transition to the Fokker 50, which in fact was a lot easier. But the chief pilot did not like the fact that I did many approaches manually, the company standard was to use the autopilot.

Even though the differences were quite manageable, without proper preparation it is not a good idea to try and operate “antique! airliners on the basis of “kick the tyres, light the fires”. That way many, too many, pilots got burned. And sadly, in some cases, literally.

Quiet interesting reading these comments, I just wonder who of you actually ever flown one of these aircraft with radial engines. Who knows what the engineer’s job is on this aircraft

As someone who has flown with both of these pilots both in airlines and on vintage aircraft I would humbly suggest that most of you who comment on pilot experience don’t know what you are talking about.

Both pilots were very well qualified on radials including P&W and Wright.

This aircraft goes back to the 1950s and in those days the Flight Engineers were only licensed as Ground Engineers. Flight Engineers handle the engines is the answer to your question.

I have no clue as to what and why on the fateful day but if you don’t know something (like pilots experience)

don’t guess

As far as licensing this is a murky world when one off ferries occur, It is not unusual to have crew licensed by one country or more flying a different registration. Particularly common with N regos. It is often done with a nod or a letter. Remember these 2 pilots received their Convair endorsement in SA a year earlier and flew the aircraft to Australia on an ZA registration.