Flying Over the Alps in a Private Jet Simulator

One of the great things about aviation is that you get to meet the most amazing people. Take Murray Simpson: he’s a pilot with something close to a million trillion hours who learnt to fly in the Royal Air Force and later spent many years flying in East Africa before turning his eye towards corporate jets. He’s incredibly talented and one of the top (maybe the top!) examiner in the UK. And he’s my friend.

These days, he works for FlightSafety International, an aviation training company with some of the best simulation equipment in the world. FlightSafety International offer training for flight crew, maintenance: you name it, they’ll teach you how to do it. I bet you could take over an airport and staff it with their training alone.

And you want to know what’s really amazing about Murray? He invited me to pop over to FlightSafety’s facility in Farnborough to have a look around and find out what a training session in a simulator is really like. I have better friends than I deserve!

I’d never been in a simulator before, although I’d seen one when Cliff did his IFR training. That simulator was a bit disappointing, if I’m honest. I expected something less like a box and something more like an amusement park ride. There was nothing wrong with it, don’t get me wrong, but it simulated dials and settings, not flying a plane. The whole point was to test you on your use of instruments, which was fair enough, but it didn’t hold a lot of interest for me.

I wasn’t quite sure what to expect when we arrived at their offices at Farnborough. The posters on the wall announced that they had “full flight” commercial aircraft simulators with high-resolution images and large field-of-view display systems built on motion platforms. So rather than just a heads-up display, the simulator was meant to recreate the motion: the platform moves in line with the visual cues to give the illusion of flight. But these weren’t for entertainment, they were for training, so I guessed it would be a minimal effect.

We started with a cup of coffee and a tour of the building to see the classrooms. It was clear that no expense was spared: there were 15-30 desks per class room with dual monitors and a large aircraft yoke on every desk. Murray showed me how the instructor could control the scenario from the front of the class and easily watch every move of the students. It looked like great fun: if I had monitors with interactive scenarios and my own yoke when I was at school, I would have paid a lot more attention to the teacher.

After a tour of the building, we reached the Flight Simulator halls. I won’t lie: it was a little bit of a dark and creepy place with large pods on black greasy mechanisms. Murray led down the stairs to see the machinery and then back up again to follow a platform along the long dark room. He stopped at a white pod that said Citation Sovereign across the side.

We crossed a narrow bridge into the pod. Inside was a small room with a trio of passenger seats and a wall of monitors on the right showing display settings and maps. Straight ahead was the cockpit. Murray chose LSGS, Sion airfield in Switzerland. He seemed to consider a couple of settings and then flicked a switch. The cockpit windows came to life, showing a long grey runway ahead and snowy hills on either side. It looked a bit like a fantasy game of a winter wonderland. Murray showed me the METAR for our flight which I pretended to be interested in. We weren’t really flying, after all, so I was unlikely to have to abort due to bad weather. Murray waved me forward. “Strap in.”

I sat down and looked around. There seemed to be straps everywhere. The dashboard was a huge collection of gauges and dials. I blinked. Could I fly this plane? It took a few minutes to start to make sense of all the gauges: there was the altimeter, and there the artificial horizon. As I spotted individual dials the dashboard began to come together. Still, it looked pretty complicated for a video of a take off.

“Strap in,” said Murray again. I confronted the most complicated seatbelt I have ever seen. There were straps everywhere. I found a shoulder belt and pulled it down. Between my legs I found a round buckle which no hint as to where I would slide in the tongue of the shoulder strap.

I’ve always rolled my eyes a bit at the cabin crew demonstration of how to use a lap belt but at that moment, I sure wished there was someone showing me how to put this thing on. Murray busied himself getting into the other seat. He didn’t say anything but I was pretty sure that, if I couldn’t even manage the seatbelt, I wasn’t going to be allowed to fly the plane, even if it wasn’t a real one.

I poked at the buckle until the tongue snapped into place. That’s when I realised that the round buckle had slots for over half a dozen straps and started making my way through the maze of them. Murray set us up for take-off configuration and politely managed not to laugh. I ended up with two slots in the buckle that were unfilled but I was clearly securely strapped in. Besides, we weren’t actually going anywhere. “Ready,” I said.

“Great. I started you on the runway. You have control.”

“I have control.” I felt silly. I mean, the display showed a lovely image of snow topped mountains and a runway stretched out before me but it was just a picture. The cockpit model was seriously detailed but it was just that, a model of a cockpit. It wasn’t real.

“We’re blocking the runway,” said Murray. “Power on?”

Right. I pushed the throttle forward and the aircraft lunged forward and to the left. Shit, rudders. I struggled to straighten out the aircraft as we pummeled down the runway. What did he say my take-off speed was? Where was the damn speedometer anyway?

“92 knots,” said Murray with a knowing look. I had no idea if that was take-off speed or how fast I was already going. I searched for the right gauge as we hurtled too fast along the runway that the plane threatened to veer off of at any moment. Finally, there we were at 92 knots and I pulled back on the yoke just to get off the ground so I wouldn’t embarrass myself by running off onto the grass at the side. Luckily, the aircraft handled like a dream and we rose into the air like a feather. My stomach sank: my rate of climb was insane, we were going to stall if I didn’t get it under control. I pushed the nose down and find the vertical speed indicator, 500 feet per minute. I unclenched the yoke and tried to breathe.

That wasn’t just some picture of a runway. I was there.

I had no time to think about it. Murray called out navigation instructions for Geneva as we rushed down the valley towards mountains that were unquestionably higher than us. I increased the rate of climb and it finally sunk in that I was nowhere near the heading he’d told me to turn onto on climb out. I could control either the rate of climb or I could stay on the heading bug but it was quite obvious I couldn’t do both, let alone watch the speed. “Trim, trim, TRIM,” shouted Murray. I couldn’t even work out which way I needed to trim and I just shook my head. No sane person on earth should have allowed me to be in charge of this aircraft.

But Murray smiled. “Over, there, see?” There was what might have been an airfield in the distance except that at that moment, the bright blue sunlit sky turned ominously grey. I glanced over, ready to cede control. Murray muttered under his breath and seemed to be searching for something on the dashboard. “Must be here somewhere,” he grumbled as I flew straight into cloud.

“Do you know I’m not instrument rated?” My voice came out as a squeak.

“You’re fine. Oh, sorry, lets get rid of this weather.” The outside flickered and it felt like a pinch to the arm. “Just a simulation,” I told myself, over and over. But it didn’t feel like a game. I was clearly in the aircraft, flying. Even when the sky flashed back to blue, there was no doubt in my mind that this was real.

“Right, got it?” I stared at the dials but Murray pointed at the airfield to our left – Geneva – and I set myself up on final approach for a straight in. We were perfectly visual. I was *finally* in trim. It should have been easy. But the aircraft was too fast and I had descended too far. “Go around,” said Murray and I pushed the power back on. A deep breath escaped as I pulled away from the runway. “I’ve got this,” I told him, in case he was wondering if I could do this at all, in case he wanted to break off the trial and take control.

Murray just tapped at the power. “You need a bit more.”

We came around again. This time I had plenty of time in the circuit to get set up. I watched the PAPI and aimed for the numbers as Murray talked me through the speed and altitude. “Don’t over-correct, keep your eyes out there, you’re fine. ”

I pulled the power off as we crossed the threshold of Geneva runway 05. My heart skipped a beat. The wheels touched the runway and I held the nose up for as long as I could. Gently and slowly the nose sank to the ground and as the aircraft began to slow, Murray looked at me and said, with utter shock in his voice, “That was perfect.”

I breathed in for the first time since we took off and look around at Geneva airfield. Here on the ground, I could see the video game quality of the landscape around me again but as I pulled onto the apron, in the pit of my stomach, I wasn’t actually sure it was an illusion. I half expected a follow-me to come out and lead me to my parking space.

Beaming from ear to ear, I started to chatter at Murray. The flight was fantastic, every movement so real. Could I do it again?

Murray flipped a switch and the world shifted. We were back at Sion, on the runway, ready to take off again, as if we’d never made that flight. “Come on then. This time, get it in trim.”

Retracing the flight for the second time, I coped a little bit better with the various demands. I had enough time to look out the window and wonder at my own reactions. The fact that we flashed back to the start and were flying to Geneva again did nothing to convince my brain that I was in a chamber in a dark room: I continued to believe that I was flying this aircraft, on track of a beautiful if somewhat unreal snowbound landscape. I started chattering again about how real it felt.

“The aircraft doesn’t handle exactly like this,” said Murray with a shrug. “I mean, it’s close, just not perfect. The flight-deck is an exact replica of a Citation Sovereign. The performance and handling is programmed using data from test flying of the actual aircraft. It’s close enough to satisfy the governing bodies that you can do Type-Rating training in the sim. Once you’ve checked out here, you can walk straight across the apron and get in the plane and fly away.” He grinned. “We’re airside. They trust us.”

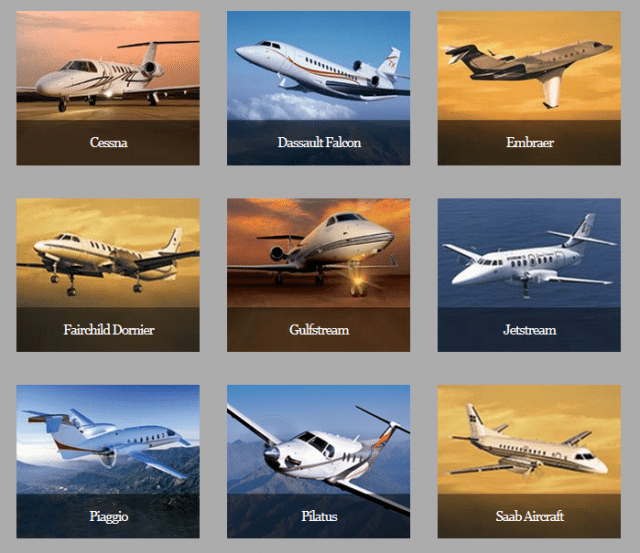

It must be amazing to work there. Flight Safety International cover 135 aircraft models and have over 300 full flight simulators. Murray and the rest of the staff at FlightSafety International could fly a different plane into a different part of the world every day and it would take them years to get through all the configurations.

Of course there’s a cost to all this and a joy-ride in one of the simulators is more than a simple little PPL like me could ever dream of. “Sure, it’s expensive,” said Murray. “But the plane costs millions. You send your zero-hour pilot here and for a tiny percentage of the overall cost of the aircraft, you’ve got a type-qualified commercial pilot trained for your aircraft in two weeks.” He made it sound like a bargain.

Pilots usually come together to be trained as a two-man flight crew and get to spend 32 hours in the sims – 16 in control and 16 in a supporting role in the right seat. And if a pilot comes on his own? “Well, then an instructor needs to sit in for 32 hours – half the money and twice the man hours.” He shrugged. “It’s not a problem, but we prefer them in pairs.”

So, if I can get together a few thousand quid and find a rich friend to join me, we could spend 32 hours in the simulator, 16 of them in control. I’ve already got £183.30 saved up so it shouldn’t take long. Maybe Murray will get me a discount if I promise to ask for someone else to instruct me.

Your travels are amazing, Sylvia. Even in a Simulator! As usual, you tell a good story. Always a joy to ‘follow’ you while pretending to keep an eye on you.

Hear,hear ! Yes, Nancy is right, Sylvia does have an amazing way with the pen.. uhm… keyboard.

But to be quite honest, I spent quite a lot of time in those “sweatboxes” and if you are in them as part of your career as an airline pilot they are not necessarily offering the fun Sylvia experienced.

Because a session can make or break a career. And not every sim. instructor is the pilots’ friend. An airline simulator session usually is run by a check pilot and some seem to have developed character traits more often attributed to the likes of the late Adolf Hitler or Saddam Hussain.

An airline pilot will routinely have to spend about 10 hours every year in one of them.

Base training, IFR renewal, winter- and summer type recurrent.

Those sessions start in the same way as a routine flight. Briefing, flight planning, NOTAMS and weather, deferred defects, fuel, loadsheet, it all starts as usual. Only the briefing room may not resemble the airline’s crew briefing room but everything else will have to be done.

If the aircraft is a turboprop and the flight is planned to cross mountains, a complicated drift-down calculation is also part of the session. During the “winter type recurrent” all kinds of problems related to, well, winter operations will be reviewed. De-icing, hold-over times, runway contamination, you name it.

During summer type-recurrent of course problems like CB activity, microbursts and other “nasties” will be encountered.

But once in the simulator the fun really starts. Of course, you never end at your destination. All sorts of problems will be thrown at the crew. Hot starts, hung starts, the whole scala of failures and problems and of course, the crew will be expected to cope.

Once on the runway, again they will find that they are “flying” the worst, most mechanically unreliable aircraft ever built.

Engines and other essential equipment will fail and the crew will have to deal with it. ACCORDING TO THE BOOK. Never will a pilot be confronted as often as in an airline simulator with the words “the book says”.

Because never mind how experienced on a particular type of aircraft, if a pilot changes airline (not really a career enhancing move because he or she will drop off the cliff called “seniority list”), every airline has it’s own books and manuals full of “SOP’s” (standard operating procedures). Woe betide the pilot who responds to the call “parking brake” with “set” if the airline prescribes the response “on”.

But the simulator can be quite a pressure cooker and if the instructor or check pilot gives multiple failures the crew will really feel the heat. E.g. if an engine has failed, the approach will be restricted to Cat 1. Cat 2 is no longer an option and the crew will have to be aware of the implications of failures on the flight.

Just to give an example.

A colleague of mine once failed a simulator session: simple enough, the check pilot who operated the simulator gave the crew an alternator failure. No big drama: In a twin-engined aircraft the remaining alternator can easily provide enough output to power all systems. The only thing may well be that “load shedding” automatically disconnects the galley.

But then this crew were given quite a few problems to solve, the weather was going down to minima of worse and then they got an engine fire to deal with.

They coped well with the drill and shut the engine down according to “the book”.

But then the pressure got the better of the captain. They prepared for an ILS down to minima. The captain forgot that with one alternator failed and the other one on the now inoperative engine they were on battery power only. By law, the battery must be able to provide electrical power for 30 minutes. In real life this may well be more, especially if the crew went through the emergency check lists and shut down all non-essential systems.

But in a simulator, of course, after 30 minutes the cockpit will suddenly become very dark.

The captain forgot about that and did not include this in his pre-approach crew briefing.

So, you already guessed what happened: At 200 feet the welcoming runway lights did not come in view, the instructor had dialled in 50 feet or so.

The captain could still have saved the day by announcing something like “continue approach, we are committed”, but he called for a go-around.

Before they could make another approach, the 30 minutes were up, the instruments went dead. They now were only on the air-driven standby horizon and could no longer make an approach.

Fortunately, this was a simulator session !

So, Sylvia, for you this may have been fun but most professional pilots DETEST simulators !

If there are professional pilots reading this, a tip:

We introduced “Andrew Never Will Fly Better” as part of the pre-flight and pre-approach crew briefing. A bit like the airline pilots’ HASELL.

A: Aircraft status. Deferred defects (if any)and their effect on the flight.

N: NOTAMS.

W: Weather.

F: Fuel status.

B: Briefing (pre-take-off of approach).

Believe me, it really works.

I thoroughly enjoyed it but Murray was mercifully light on the emergencies. I can see that it would be a different situation if I had to deal with an aircraft falling apart around me!

That. Sounds. Amazing.

Thanks for sharing the journey-not-journey. :)

Sylvia,

A simulator usually is fun as long as you are not in the “sweatbox” as part of the job, being judged by an examiner.

Having said that, I usually enjoyed Flight Safety or Simuflite courses. Why ? Because the pilot is employed – as a rule – by a private operator (unless he or she is in the fortunate position to own the aircraft him- or herself).

The owner, operator or purchaser of a private aircraft sophisticated enough to require a type-rating and training in an advanced simulator is the customer and the training centre is contracted to train the crew. This means that the training organisation is committed to making sure that the crew will obtain the required skills and, unless totally hopeless, will PASS.

An airline training environment is particularly unforgiving. Whereas at least 80% of candidates going through the likes of Flight Safety will pass, airlines often will fail more than half of the “ab initio” candidates and often even fail crew members who are coming up for type-rating or IFR renewals. Like in the example I mentioned, where that particular captain was demoted and flew as co-pilot for a year before he could be considered again for promotion back to command.