Twin Pioneer Down in Libya: Structural Failure in 1956

On the 7th of December 1957, a Scottish Aviation Twin Pioneer 1, registration G-AOEO, departed an airstrip at Anshan in Libya for a routine flight to Tripoli-Idris Airport. There were two crew and four passengers on board, including David McKintyre, the co-founder of Scottish Aviation Limited.

They never arrived.

The Twin Pioneer was the most successful aircraft for Scottish Aviation in the 1950s: a STOL (short take-off and landing) propeller plane designed as a twin-engined follow-up to the Pioneer for civil and military use. The Twin Pioneer could take off and land with a ground run of just 275 metres (900 feet) making it a popular transport option in areas with few or no official runways. The British Royal Air Force purchased 39 of the aircraft and, at the end of the 1950s, the RAF used them extensively for moving troops and supplies around Aden, Malaysia, Borneo and other conflict zones.

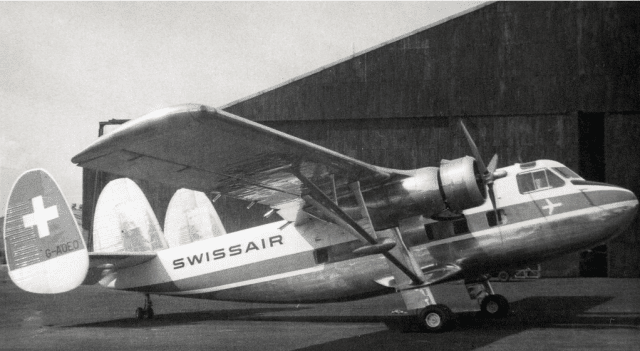

The aircraft registered as G-AOEO was one of twenty-three Twin Pioneer Series 1 built (along with 32 of the military variant). G-AOEO’s first flight was on the 26th of August 1956, after which it was delivered to Swissair for short field flying in the alps. It was the only Scottish Aviation Twin Pioneer in red and white: Swissair colours. Swissair history explains that the tail had the Swissair arrow painted on instead of the Swiss cross because the aircraft remained registered in the UK; however, this fantastic photo of G-AOEO taken by Jim Cain in 1956 shows the Swiss cross above the UK registration.

(As an aside: I highly recommend visiting Ayronautica’s Flickr album of Scottish Aviation Pioneers, a fine collection of aviation photographs taken by his father which includes a bit of history for each aircraft.)

Swissair tested the Twin Pioneer for a short period on various runways, including Davis, Zermatt, St Moritz and La-Chaucer-de-Fonds. After three months, they returned the aircraft and ordered a different Twin Pioneer (HB-HOX) which they used for “photographic flights”.

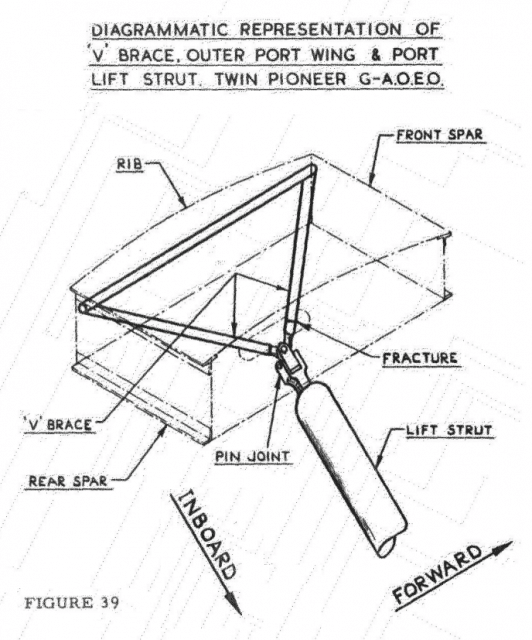

In late 1957, Scottish Aviation took G-AOEO to Africa as a part of a sales tour. The combination of the tail wheel and high wings helped the aircraft land and take-off in very short distances, but the real innovation was a high-lift device incorporated into the wing. The wings were made of two outer wing panels and a single central piece which carried the fuselage and the two engines. Front and rear spars formed the main structural members of the wings. Pin joints connected the spars of the outer wing panel to the spars of the centre section. These pin joints had hinge-like connections, which allowed the wings to flex in flight.

Each outer wing panel had a “V brace”, a triangle of steel tubing located halfway between the pin joints and the wing tip. The lift strut extended from the base of the undercarriage to the V-brace on the outer wing, offering a strong point for the lift strut connection. The lift strut restricted the flexing of the wing and bore the bulk of the flight loads.

When Libya became an independent country in December 1951, it was considered one of the poorest countries in the world. In the 1930s, geologists concluded that Libya did not hold commercial oil reserves. Then oil was discovered in Algeria in the 1950s which reawakened interest in oil exploration in the area. Libyan oil was confirmed in 1957, offering a massive infusion of interest and economic support to a country that desperately needed it.

Various oil companies quickly set up bases in Libya, including Esso Petroleum Ltd. (later Exxon). The transport infrastructure was weak; the oil companies required better transportation across the desert and had the funds to pay for it. Scottish Airlines were quick to pitch the Twin Pioneer as a solution to corporate exploration and development problems.

From a pilot’s point of view, flying in Libya must have seemed like time travelling. There were no navigational aids and precious few visual markers in the desert, so once the flight route left the coast, the pilots depended on dead reckoning for navigation.

Ken Honey flew in Tripoli from 1957 to 1959 as a first officer for Silver City Airways. He has written an article about his experiences there which is hosted on the British Caledonian tribute website (which I also highly recommend; it is an amazing resource).

Fortunately all our aircraft were fitted with RAF wartime Drift Sights so it was possible to observe the drift on any heading. The basis of the unit was a powerful magnifying glass in a frame aligned with the aircraft that showed the movement over the earth’s surface directly below the aircraft.Fitted above this small display was a transparent rotatable cover with parallel lines that could be aligned to any moving object at ground level. The drift was then read off a small scale on the rim of the unit. We flew a magnetic heading to coordinates on a Mercator’s Chart and applied a drift correction every ten minutes. In general, the weather was quiet over the desert most of the time with a steady wind, so we were very accurate with our navigation. On early trips what was thought of as a featureless desert, slowly came alive with sand sea areas, small escarpments, different colour sand, also an odd track, all of which helped us. To me desert flying was fascinating; we flew over the whole of Libya by this never to be repeated, well known system of dead reckoning navigation. The topographical maps for Libya at the time were not very accurate but we did use them to write our own observations for future reference.

The Twin Pioneer G-AOEO arrived in Tripoli, the capital city of Libya, in December 1957 to carry out demonstration flights for Esso management. The flight crew were given a rest day in Tripoli before the first flight.

On the 7th of December, the Managing Director and co-founder of Scottish Aviation welcomed two passengers, a senior ESSO manager and a representative from a geophysics company, to join him for a flight in the demonstration aircraft. The pilot was supported by a Silver City Airways pilot to help with navigation.

They flew three and a half hours to the Esso camp at Wadi al Atshan, 345 nautical miles from Tripoli. Once there, the high-ranking guests were treated to a 45 minute demonstration flight in the local area. Then they refueled at Atshan ready for the flight back to Tripoli.

They departed from the small airfield at 14:27 local time, with an ETA at Tripoli of 18:00.

When night fell and the Twin Pioneer still hadn’t arrived, a search and rescue plan was coordinated for the morning. At first light, a DC-3 flew to the landing sites on the route from Atshan and Tripoli hoping to find the Twin Pioneer safely on the ground at an alternate destination. Within a few hours, the US Air Force began to search the area with support from Silver City Airline and an RAF Shackleton which flew in from Malta.

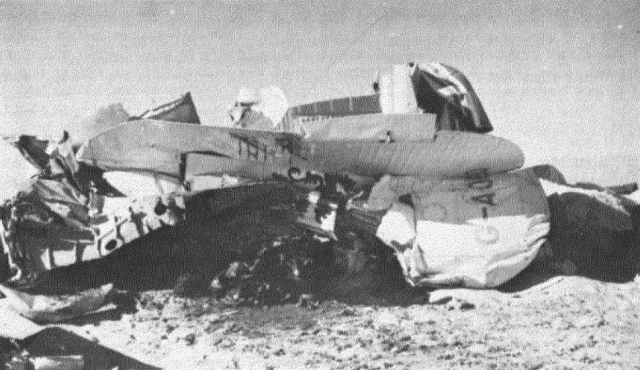

The crash site was discovered that afternoon: the Twin Pioneer had disintegrated with the force of the impact. It was immediately clear that there could be no survivors.

The outer panel from the port wing was found about 1,200 yards (1,100 metres) away from the wreckage. The forward tube of the V-brace was broken. This transferred the upward forces of the wing to the rear tube, which effectively tore itself out of the wing. Once the lift strut was disconnected, the outer wing folded upwards and backwards, tearing itself away from the pin joints.

At the first view of the crash site it was quite obvious what had happened as one very complete looking wing lay on the sand just over a hundred yards from the main wreckage. It had become detached during flight.The main wreckage area was very small indicating that the remainder of the aircraft had dived at great speed into the sand leaving the crumpled tailplane on the top of this sad pile.

When they examined the broken parts of the V-Brace, there were clear fatigue cracks at both ends of the forward tube, which is where the break started.

From the accident report (courtesy of BAAA-ACRO:

The forward and rear tubes are connected to the pin joint attachment of the lift strut by means of fork-ended cadmium plated steel fittings plugged into the end of each tube and secured to the tube by shear bushes and tubular rivets. Two fatigue cracks had initiated on the forward tube at diametrically opposed points on the bore of one of the shear bushes situated about four inches up the tube from the pin joint; the cracks propagated circumferentially around the tube, and final separation had occurred in tension.

Now obviously the tubes needed to be able to take normal loads and had undergone fatigue testing to establish how long they could safely be used before risking fatigue issues, without generating unnecessary maintenance issues and costs. This wasn’t a simple calculation: the safe life of the 4T2 steel tubes was influenced by the weight of the aircraft, the speeds flown, the type of the flight and the altitudes flown. Gust tests were used to replicate the number of 10-foot-per-second gusts or load reversals that the aircraft was likely to experience during its operations. In reality, gusts varies greatly by altitude, with the frequency being much greater near the ground.

As a result of the tests, Scottish Aviation concluded that the 4T2 tubes had a safe life of approximately 2,500 hours, based on the aircraft being operated on flights that were at or above 2,000 feet. If the aircraft regularly operated at or above 5,000 feet, the safe life increased to 10,000 hours.

Replacing the tubes this frequently meant that the V-brace was not a great solution from an economic and maintenance point of view. The Twin Pioneers built in 1957 replaced the 4T2 steel tubing with T50 steel tubing, which were able to deal with the strain for longer periods.

G-AOEO was scheduled to have its V-brace tubes replaced with T50 steel tubing before she reached 2,000 hours, which must have seen like an excess of caution at the time.

When the forward tube failed in Libya, rendering the aircraft completely uncontrollable, G-AOEO had only flown 563 hours and 55 minutes.

The problem was that the 2,500 hours safe life was based on an assumption of a certain type of flying. But G-AOEO was never in normal operations. She flew at lower altitudes for demonstration flights and testing, first for Swiss Air and then back with Scottish Airlines, without any tracking or even understanding of how these low-level operations were constantly reducing the safe life of the forward tubing.

After the accident, the V-brace was limited for a safe fatigue life of just 500 hours.

ICAO Accident Digest No.9, Circular 56-AN/51 (240-244)

PROBABLE CAUSE: The failure in fatigue of the forward tube of the “V brace” structure in the outer panel of the port wing. This failure led to the breaking away of the outer panel of the port wing from the aircraft in flight. The aircraft was then rendered completely uncontrollable and dived vertically to the ground.

The final report recommended that all operators maintain detailed records of all flights. If a safe fatigue life was specified covering a variety of altitudes and types of operations, then it would be trivial to understand the actual fatigue life of the components of the aircraft under heavy loads.

This lesson would have been good to learn before the fuselage burst open on the Aloha Airways flight 243 in 1988, another case of the aircraft operations not being in line with the assumptions made for predicting fatigue.

An aircraft has three parameters: physical age, actual flight time, and how many times it has taken off and landed: cycles. Although the aircraft wasn’t reaching full pressure differential, the repeated pressurisation and depressurisation of the aircraft was causing high stress on the fuselage, much more so than the actual hours in flight. Also, Aloha Airline’s fleet flew exclusively around small Pacific islands, a humid climate and surrounded by salt water. The Hawaiian environment was much more corrosive than for the ‘average’ aircraft. So at nineteen years old, the aircraft had suffered higher than normal levels of metal fatigue.

The death of David McIntyre, the first pilot to overfly Mount Everest and the co-founder of Scottish Aviation with the Duke of Hamilton, signified a loss to Scottish Aviation from which it would never recover. As a memorial, the McIntyre VIP suite for visiting dignitaries was unveiled at Prestwick Airport as a part of the airport’s 60th birthday celebration in 1995.

The wikipedia article on drift sights is fascinating.

A lot of motorcycle racers drill lightening holes into everything, until the bike resembles a swiss cheese. They then rediscover the facts of stress propagation the hard way. They only fall 3 or 4 feet, but the horizontal velocity component is a stern teacher.

Ken Honey’s description of the desert flights was really interesting. Talking about T50 steel tubing was also interesting. And also this bit, “An aircraft has three parameters: physical age, actual flight time, and how many times it has taken off and landed: cycles.”

I really enjoy your posts that are educational and historical, aside from the tragedy of the flight, the posts are quite interesting and enjoyable.

Thanks!

Hi Sylvia,

This may be of interest to you. There was a recent crash of a PA-24 as a result of engine failure in the USA. Two persons on board – both survived, although seriously injured. The passenger was Dr Carrie Madej. The pilot her boyfriend see:

Controversial Christian Doctor, Carrie Madej, Labeled Wild Conspiracy Theorist, Involved in Mysterious Plane Crash; FAA Investigating

https://www.publishedreporter.com/2022/06/30/controversial-christian-doctor-carrie-madej-labeled-wild-conspiracy-theorist-involved-in-mysterious-plane-crash-faa-investigating/

She is now back home and talks about her experience from 46 mins 50 secs in the following video.

DR. CARRIE MADEJ GIVES AN UPDATE ON HER HEALTH CONDITION AND TALKS ABOUT HER PLANE CRASH (Video)

https://gospelnewsnetwork.org/2022/07/01/dr-carrie-madej-gives-an-update-on-her-health-condition-and-talks-about-her-plane-crash-video/

The flight track at https://de.flightaware.com/live/flight/N14FC shows a U-turn, presumably because the pilot picked a suitable landing site that allowed both occupants to survive the crash.

In the video you linked, Madej comes on at 46:50, but starts talking about the actual crash, their injuries and the rescue operation from 56:00. It’s not for the squeamish.

I don’t think there’s anything mysterious about the crash.