The Real “Bionic Man”

Some of you may have spotted the recent comments on Wingless Flight in the M2-F1 by aerospace journalist and author Nigel Macknight, who had written about NASA’s M2-F2 pilot Milt Thomson, whom he knew when he was editing and publishing Space Flight News back in the 1980s. In the article Nigel was commenting on, I had linked to a video of the title sequence for The Six Million Dollar Man TV series, which was inspired by the accident that befell Thompson’s colleague, Bruce Peterson, who crashed in the M2-F2 in 1967.

Nigel knew the story well, as he had interviewed Peterson about the crash. Obviously, I rushed to point out that we would all like to know more about this and asked if he would be so kind as to allow me to reprint the article.

To my delight, Nigel not only was happy to share his work with us, he created a new piece, especially written for Fear of Landing.

The Real “Bionic Man”

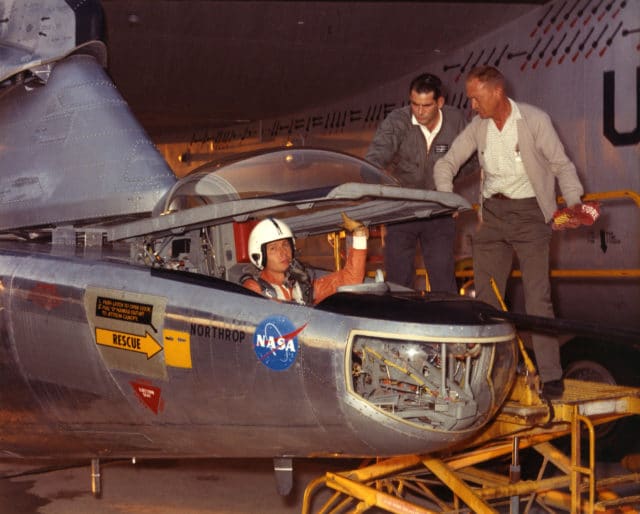

NASA test pilot Bruce Peterson

by Nigel Macknight

The “Bionic Man” really did exist! The American TV series The Six Million Dollar Man was popular around the world and featured a dramatic title sequence in which a NASA research plane, its pilot attempting a hazardous landing, tumbles out of control and comes to rest upside-down. The crash film is genuine. The aircraft was one of several radical “wingless” aircraft NASA tested in the 1960s and ’70s, and the pilot was one Bruce Peterson.

Miraculously, Peterson survived this crash after extensive surgery – although to say he possessed superhuman powers thereafter, in the manner of the television character he inspired, might be stretching the truth somewhat!

I was fortunate enough to interview Bruce for my magazine, Spaceflight News, early in 1986, and found the experience highly enlightening. He reflected on his accident with seriousness but also philosophical good humour, with no hint of self-pity. He explained how several factors contributed to the crash, how his aircraft became unstable, how a rescue helicopter hovering too near to his landing point had distracted him, how errors were made that could have been avoided.

What he didn’t mention – because he knew I already knew – was that he and his plane only had that one, single chance of landing. There was no possibility of aborting the approach, making a circuit and trying again in the way that the pilot of a conventional aircraft could have done … because Peterson’s plane was a glider. A highly exotic glider, certainly – as befitted its role as a research aircraft at the very cutting edge of aeronautical exploration – but a glider nonetheless. Air-launched at a height of 45,000 feet from the wing of a B-52 mothership, it had a rocket engine to boost it to great altitude, but its design was such that once its ascent-phase propellant supply was expended it glided back to earth with only the whistle of the wind for company … and just that one, single chance of landing.

As it so happened, Peterson’s flight on the day of the crash was not going to have a powered ascent phase. It was to be conducted wholly in the gliding mode, because it was a particular aspect of the glide phase that was at that time giving NASA cause for concern and needed further investigation.

The plane was the Northrop M2-F2, one of a series of research craft that were termed Manned Lifting Bodies, and informally referred to within the programme as “Bods”. A key characteristic of these extraordinary experimental aircraft was that they descended extremely steeply and rapidly – far more so than any conventional glider – for they had been built to pioneer techniques and technologies that would one day lead to the Space Shuttle, and at this particular stage (1967) in the evolutionary process it seemed the solution might lie in an essentially wingless aircraft, as wings generate drag, and drag at high speeds generates heat, so wings would be prone to burning off during re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere.

No wings meant no lift, though – or very little. The only lift the M2-F2 produced was the very limited amount that came from the shape of its half-conical fuselage, which was modelled on the shape of the ballistic re-entry capsules employed with such great success on NASA’s Mercury, Gemini and Apollo manned space missions. For the record, the M2-F2’s descent rate was typically 15,000 feet per minute – and that in itself is a record, making it the fastest-descending aircraft type of all time.

If, not unnaturally, an aircraft with no wings fell like a stone, it follows that it required a rare breed of pilot to fly such an unconventional and demanding machine. It took a special talent to perform the tricky pre-flare manoeuvre seconds before landing, calculating the precise moment to ignite two tiny landing-rockets that would burn just long enough to flatten out the rate and angle of the craft’s descent to avert catastrophe, then lowering the undercarriage at the very last instant before touchdown so the extra drag this caused wouldn’t make things even more difficult.

But it all went horribly wrong on the 10th of May 1967. A severe roll instability problem that had been experienced on earlier flights – which, in line with the nature of test flying, Peterson was investigating on this flight – got the better of him. Another NASA test pilot, Milton Thompson, had been the first to encounter the problem, and he had been able to manage the situation by adjusting the manual aileron/rudder interconnection control in the cockpit. NASA thought they had the problem licked, but they hadn’t. USAF test pilot Jerauld Gentry, another ace flyer on the lifting-body programme, made the next flight and found that out. The high-frequency buffeting – a severe lateral oscillation – started as soon as the aircraft’s nose was lowered, and it almost cost Gentry his life.

On the next flight, Bruce Peterson’s mission was to enter the danger zone and take a hard look at the problem.

Launch from beneath the wing of the B-52 went as normal and all seemed fine. But circumstances were conspiring to cause Peterson’s accident right from the start. A right-to-left crosswind developed immediately after launch and Peterson told me there may well have been some windshear effects prevalent, too. To counter the crosswind, he decided he was going to land across the runway that the “Bods” normally landed on.

The first part of the flight passed without incident, but things went badly awry soon after Peterson executed his turn onto finals. At this stage of the flight, he was to push the control stick forward to flatten-out the craft’s angle of attack and see if the lateral oscillation problem struck again. Peterson: “When I pushed over, the nose of the aircraft just slid out to the right. I tried to counter that with rudder to bring the nose back and the airplane went into severe lateral oscillations and was uncontrollable, with very high rates and very high bank angles.”

He recognised that the only way he was going to recover was to pull back on the stick and increase the airplane’s angle of attack again, then time his pull-out to get as near as possible to a wings-level orientation for landing. As things turned out, Peterson was able to do just that, but it didn’t prevent the inexorable sequence of events that would conclude with the crash.

Before he was able to bring the oscillations under control – Bruce told me with cool test-pilot understatement – he, “got slammed around in the cockpit quite severely”.

The aircraft lurched wildly, his helmeted head was hammered from side to side against the cockpit canopy. “It was like a series of shots from a fist and it dazed me quite badly,” he recounted. Seeing a potentially catastrophic situation develop, one of the two test pilots flying chase-aircraft alongside shouted for him to eject while he still could, but Bruce elected to press on and attempt to coax his aircraft back down to the ground in one piece.

He managed to bring the violent oscillation under control, but by that time he had strayed well away from the designated landing area. This was Rogers Dry Lake in California, not far from Death Valley, where nature has created seemingly ideal landing sites in the form of vast, dried-up brine lakes. The hard salt surface is very smooth – but can be notoriously deceptive to pilots judging their height above it on their approach to landing.

The designated landing zone had markings set out in black on the salt. But having missed that now, deprived of these visual cues as to his altitude – viewing only the flat, featureless expanse of white, with no reference points to aim at – Peterson’s situation was worsening by the second. That is when he saw the medivac helicopter right in front of him. The one that would have been two miles behind him if things had gone to plan.

For a few dreadful moments Bruce thought he was going to collide with the distinctive banana-shaped ’copter, a tandem-rotor Piasecki. “I saw the helicopter and told the pilot to move west – because that was the direction he was pointed in – and I figured I could go in behind him. Finishing my flare-out at maybe 20, 25 feet – it was hard to tell – I thought to myself maybe I’d have to go underneath him, so I flared-out and he was on my right-hand side as I passed him.”

Film of the accident shot from the ground reveals just how close Bruce’s stricken plane got to the Piasecki. At one point, they appear almost to touch, so tight is the clearance.

“Either I caught his rotor-wash or I misjudged my height above the lake – I’m not sure which was the case” – but I put the landing gear down, and as the gear came down I felt this contact with the lake.”

He had decided moments earlier to fire the “instant lift-over-drag” rockets to help flatten the final stage of the landing. “I know I must have used them as I’d planned, because when they checked-over the wreckage they found there was no fuel left in the propellant tanks. Their entire eight-second burn had been expended”. Peterson had managed skilful avoiding action – only, by a stroke of bitter ill luck, to strike the ground a split-second before his landing gear had fully deployed.

Peterson’s plane smote the salt surface at 217mph. It reared back into the air momentarily then struck the salt again, rolling six times – including a dreadful end-over-end roll – before it slid to a standstill, on its back, and lay in a deathly silence broken only by the pops of metal cooling and the hiss from ruptured fluid-lines.

With no propellant aboard, fortunately there was no fire. But in the furious succession of tumbles the aircraft’s cockpit canopy had been torn off, exposing Bruce’s head, so that as the plane skidded to a halt his crash helmet and oxygen mask were ripped off and his face was dragged along the abrasive surface, tearing open his nose and mouth and packing them full of salt.

“The last thing I remember about the flight itself is the airplane nosing over and then starting to roll.

“Then a bunch of debris hit me in the face.”

Grievously injured, Peterson lapsed in and out of consciousness. In momentary flashes of awareness he could assess his situation, the grim details of which he relayed to me with calm detachment: “I remember being upside-down and not being able to see anything – hanging in my straps, which was very uncomfortable – and knowing I was badly hurt. Although I was barely conscious at that point, I do remember someone saying, ‘He’s dead’.”

He also remembers how someone on the scene vomited at the sight of his injuries. But Bruce managed to mumble something and, seeing signs of life, helpers came closer to the inverted rocket-plane and started to get him out.

By this time a doctor had clambered from the helicopter Bruce had so narrowly avoided. Seeing he was having difficulty breathing, the doctor pulled a knife and began performing an emergency tracheotomy, at which point Peterson “managed to say something derogatory” to get him to remove the blade from his throat.

Describing the accident to me nearly two decades later, Bruce still had a scar on his throat as a memento of the day he nearly died, but that hurried tracheotomy was never completed. In a critical state, he was taken in the rescue helicopter to the hospital on Edwards Air Force Base for life-saving attention. A few days later he was transferred by C-130 transport plane to March Air Force Base near San Bernardino, about 50 miles east of Los Angeles, for further complicated surgery.

Looking at the crash with the benefit of hindsight, how did Bruce feel about the events of that fateful day? “Like most accidents, it’s usually a combination of things that get you. I thought I was going to make it until the very moment that I crashed. I was only half-a-second from making it anyway, because the landing gear takes one second to come down and the traces left by the airplane on the lakebed show that the antenna protruding from the underside of the airplane touched the ground first, followed by the main landing-gear doors further on down the lakebed.

“As a matter of fact, it would have been a very smooth landing if the landing-gear had just had that extra half-a-second to fully lock down.”

When one of the main landing-gear doors caught the ground before the other, it set the M2-F2 tumbling. Ironically, though, it also helped to save Bruce’s life, as Milt Thompson – a witness to the crash – explained to me: “That tumbling motion dissipated a lot of the energy of the accident. We actually had accelerometers attached to his body on that flight, and the maximum G-force he saw during the crash was only 4G.”

Amazingly, against all the odds, Bruce fought his way back to test flying duties with NASA. He had lost an eye in the accident, so sported a dashing black eye patch. Explaining to me with a shrug the miracle that was the resumption of his flying career, his capacity for self-deprecating humour did not desert him: “There was a ready market for one-eyed test pilots.”

When Peterson finally left NASA, he took up a post at the Northrop Corporation, working on their B-2 bomber project, which was at that time a closely-guarded secret. The story had gone full-circle, for it was Northrop that built the M2-F2 that had so nearly taken his life.

And it didn’t have wings, either. It was one big wing!

© Nigel Macknight 2020

I’d like to thank Nigel again for this excellent insight into the M2-F2 crash. I hope you will all join me in encouraging Nigel to share more of his stories with us.

A great story about one heck of a brave man. Yes, I am old enough to remember the TV series “The Six Million Dollar Man”, though I never knew that it was based on a real-life (fortunately live!) man.

No, I would never attempt this kind of suicide mission. Another man who was just as cool was Neil Williams, in the seventees an aerobatic instructor with the Tiger Club. Neil was very critical of my aerobatic skills. Another aerobatic instructor whom I had a few lessons with was Victor Ostapenko, a Russian ace and test pilot. He instructed on a Yak at Weston near my home. was tested. He had tested the Russian space shuttle. It was never launched, but suspended from – if I remember correctly – a “Bear” bomber. Victor told me that it was a step into the unknown: when he was released there had been no way of knowing whether he would survive or not. My question if he had not been afraid was answered with a shrug: “It was my duty”.

Thanks for that fantastic story Sylvia!

Actually, more a thank you to Nigel Macknight for a well-written and interesting piece.

Small world. When I was working DoD contract in the former USSR, Victor’s father, Pyotr Ostapenko and his family became friends with whom I enjoyed many pleasant hours. If memory serves me correctly, Pyotr passed away about 10 years back. He must have been well into his eighties.

My last night on the job, he threw a fighter pilot’s party. I got to share toast to 1/2 a dozen test pilots and swap, “and there I was stories.” At the end of the evening Pyotr gave me a set of his Senior Aviator Wings, I placed them in my shadow box along side my USMC wings.

Wow, that is fantastic that you knew his father. The aviation world is terribly small sometimes but even so!

OK Cliff, I stand corrected. Thank you, Sylvia, for publishing Nigel’s account.

;-)

I hadn’t seen those pictures before either. That was a lot of new info I hadn’t heard too.

A fascinating essay. I was done with TV by then but knew of the show and IIRC the fact that the opening was real rather than an effect. (I was interested in space — much later I actually filled out an application to be a mission specialist on the shuttle — and hung around with many people interested in anything that might make going to and from space more routine.) But the detail in this essay is fantastic, including the fact that he \almost// got the beast on the ground safely; a seriously impressive piloting job after the beating he’d taken on the way down. Thanks for putting this up.

I just re-read the november 2019 precursor to this entry, which makes it even more interesting !

I don’t want to spoil the fun, just go back into the old blogs, read it in combination with this week’s entry and enjoy !

Thank you Sylvia and Nigel.

First we learned about Miss Beaujolais, now about the almost-bionic man: Sylvia’s blog attracts amazing commenters!

Mendel,

I agree totally, and it is an honour to be allowed to post some of my “adventures”. I obtained my PPL in Nigeria and my CPL in 1969 in the Netherlands. Aviation was such a different world then.

Igeaux, Victor Ostapenko was an aerobatic instructor working from Weston in Ireland. It was bought by a developer, Jim Mansfield, who wanted to turn it into a bizjet hub. Mansfield owned several hotels and had a habit of building sometimes large extensions or conference halls first, and apply for planning permission later. The runway at Weston was a bit short for his own Cessna 650, he solved this by building a long parallel taxiway. He hoped to turn that into the main runway eventually, but the Irish Aviation Authority blocked that, there were also protests from the local residents. A not unusual tactic: buy a plot cheap because it is near an already existing aerodrome, build houses, sell them and then the residents form an anti-noise committee. If the aerodrome gets closed, the value of the surrounding properties of course will go up.

But during that period, now more than 10 years ago, controlled airspace was established that lowered the free space over Weston and virtually stopped aerobatic activities. Weston got ATC, a non-precision approach, even ATIS. With modern technology, air traffic near Weston could be monitored. Radar images were transplanted to Weston ATC.

Victor, and the Yak 52 (there were at least two, one privately owned) disappeared. It all came to an end again with the recession, 11 years ago. The banks took control of Mansfield’s properties. He died a few years later, some hotels were returned to his family but Weston, even before the Corona outbreak, was sold and did not really recover.

I don’t know where Victor went. He spent his time alternatively here and in Russia. I only had a few lessons from him, I could not really afford enough to become competent, so I doubt that he would remember me.

But, Igeaux, if you do speak to him, give him my regards.

Fascinating story, courageous man! Thanks for posting it, Sylvia!!