The Mystery of the Hawaii Clipper

Pan American Airways was founded in 1927 to offer air mail services as a response to German-owned Colombian carrier SCADTA who was moving north from Colombia and lobbying hard for landing rights in the Panama Canal Zone. The US government approved Pan Am’s mail delivery contract and protected it from US competitors, glad that SCADTA would have competition in bidding for routes between Latin America and the United States. Pan American Airways grew rapidly with a virtual monopoly on foreign routes.

Pam Am became well known for its rigorous training of its flight crews, including long-distance flight, over-water navigation, engine repair and even celestial navigation for night flights. Long before the advent of instrument navigation, Pan Am pilots would use dead reckoning and timed turns in bad weather. They dealt with fogged-in harbours by landing out to sea and taxiiing their planes into port.

Pan Am’s “Clipper Era” began in 1931. In the following 15 years, Pan Am put 28 Clippers into service to provide intercontinental travel. The name was meant to evoke the 19th century clipper ships. These aircraft were in competition with ocean liners and offered first-class seats and luxury meals. They established their trans-Pacific airmail service in 1935 and began carrying passengers in October 1936. The flying boat service connected San Francisco, California to Manila Bay, Philippines, with stops at Pearl Harbor, Midway Atoll, Wake Island and Guam.

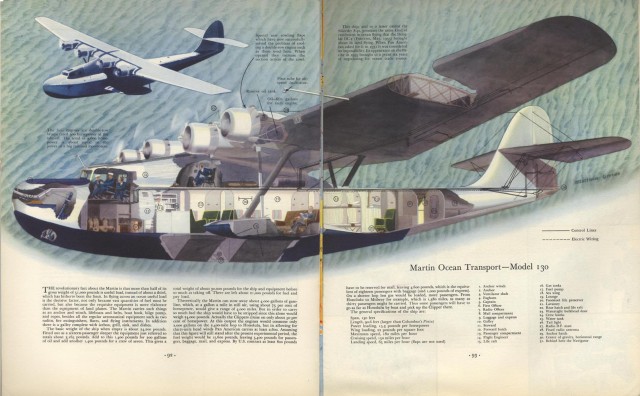

The Martin M-130 was an all-metal flying boat with four powerful piston engines, designed and developed to meet Pan Am’s requirements for a trans-Pacific aircraft. There were three M-130’s built, the China Clipper, the Philippine Clipper, and the Hawaii Clipper. A fourth flying boat, an M-156 called the Russian Clipper, was built for the Soviet Union. They were officially called Martin Ocean Transports but to the public they, and later all of Pan Am’s large flying boats, were known as the China Clippers. The weekly passenger flights across the Pacific began in October 1936 when the Hawaii Clipper left San Francisco for Manila, Philippines.

On the 23rd of July of 1938, the Hawaii Clipper was scheduled for Trip No. 229 departing from Alameda, California for its scheduled flight to Manila. The aircraft was inspected and routine service for “long airplane service” was carried out. A test flight of three hours was conducted by the flight crew the day before the scheduled departure, including an emergency landing and an “abandon ship” drill. For the “abandon ship” drill, the left raft is inflated and put overside with the crew and emergency equipment aboard. The crew set up the emergency radio and establish communication with shore stations.

The M-130 had six watercraft compartments: the aircraft could remain afloat so long as at least two of them remained watertight. The aircraft also held life rafts, a saltwater still, marker balloons, flares and food for 15 people for a month. The wings had orange stripes painted on top to ensure it would be visible to search and rescue.

There were six passengers and nine crew: Captain, First Officer, Second Officer, Third Officer, Fourth Officer, Engineer Officer, Assistant Engineer Officer, Radio Officer and Flight Steward. The captain had 9,200 hours flight time, of which 1,626 were “in Trans-Pacific operation” and 1,614 hours were in the aircraft. All of the crew had the required ratings for the flight and were in good physical conditions with all having a thousand hours flying experience or more. The aircraft had had a total flying time of 4,752 hours and 55 minutes before departing Alameda.

It departed Alameda on the 23rd of July and experienced better than expected weather for the first leg; it arrived at Honolulu the following day. At Honolulu, the aircraft was inspected and “over-night airplane service” was carried out. On the 25th, the flight continued on schedule from Honolulu and arrived at Midway Atoll, an atoll equidistant between North America and Asia on the 26th.

The clipper departed Midway Atoll on the 26th and flew a southerly route to avoid weather, arriving at its next stop, Wake Island, on the 27th. Wake Island is 3,698 km (2,298 miles) east of Guam, their next stop. Wake Island is one of the most isolated islands in the world. Both the Hawaii Clipper and the eastbound Philippine Clipper had an overnight stop on Wake Island that night. Both aircraft were inspected and had the over-night airplane service. The crew of the Philippine Clipper said that the entire crew of the Hawaii Clipper were in the best of spirits and said that their trip so far had been comfortable and normal.

The Hawaii Clipper continued on its westbound route and on the 28th of July 1938 the flight arrived in Guam at 05:55 UTC. The flight so far had been uneventful and the ordinary routine radio contacts were maintained throughout. Again, as per company procedure, the aircraft was inspected and the over-night airplane service was carried out. No irregularities were reported by the Flight Engineer nor detected by the chief mechanics at any of the airports with overnight stops.

The next flight was the last leg of its westbound route to Manila. The aircraft had 2,550 US gallons of gasoline on board, allowing an endurance of 17 hours and 30 minutes in the cruise. The flight times allowed 14 hours and 50 minutes of daylight for the flight. The flight was expected to take 12 hours and 30 minutes cruising at 7,800 feet.

The Hawaii Clipper departed Guam at 19:38 UTC (03:39 Manila time), which involved taxiing out to sea; it actually took off from the water 29 minutes later. Pan Am had a radio facility at Guam who would remain on guard until the aircraft landed at Manila. Radio facilities in Panay and Manila were standing guard, which meant that someone was monitoring at all three stations at all times during the flight. In addition, other Pan American Airways radio stations were listening out. The aircraft had two independent transmitters which could communicate on assigned frequencies or on the international distress frequency of 500 kilocycles.

At 03:30 UTC the aircraft had 1,420 gallons of fuel remaining, enough for over 10 hours at normal cruise. There was plenty of fuel to reach Manila with a few hours to spare. Radio communications had been standard throughout the flight.

04:00 UTC The radio operator at Panay received a routine report.

“Flying in rough air at 9100 feet. Temperature 13 degree centigrade. Wind 19 knots per hour from 247 degree. Position Latitude 12 degree 27′ N. Longitude 130 degree 40′ E dead reckoning. Ground speed made good 112 knots. Desired track 282 degree, Rain. During past hour cloud conditions have varied. 10/10ths of sky above covered by strato cumulus clouds, base 9200 feet. Clouds below, 10/10ths of sky covered by cumulus clouds whose tops were 9200 feet. 5/10ths of the hour on instruments. Last direction finder bearing from Manila 101 degree.”

The radio operator acknowledged the call and offered to transmit the weather sequence reports based on the most recent observations compiled and relayed to him by the Philippine Stations.

The response from the Hawaii Clipper was received as follows.

“Stand by for one minute before sending as I am having trouble with rain static.”

04:12 UTC The Panay radio operator called the Clipper back to give them the weather sequences. The call was not acknowledged.

The Panay radio operator continued to call the Clipper but received no response.

04:15 The Panay radio operator sent the Clipper’s position report from 15 minutes earlier to Manila.

04:35 The Pan Am Communications Superintendent, Pacific Division in Alameda, California was notified that there was a communications failure between the ground stations and the Hawaii Clipper.

04:49 Pan American Airways requested all Philippine stations to stand by on emergency frequencies. This is standard emergency procedure for any interruption of communications between shore stations and aircraft. At this stage, it was unclear whether there was cause for alarm, as interruptions to communications were not uncommon.

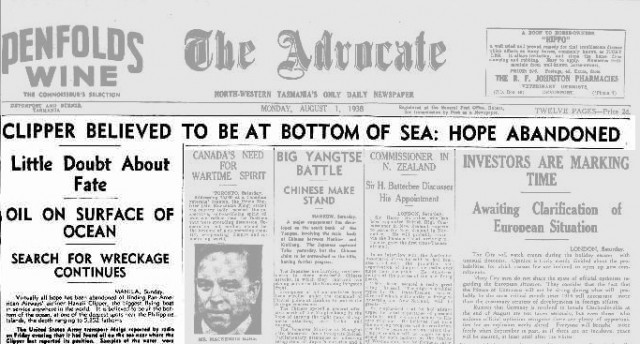

09:00 The Hawaii Clipper was due to arrive at Manila. Up until this point, it was hoped that the aircraft had suffered a communications failure but was still en route to her destination. The Naval Commandant, at the request of Pan American Airways, ordered all Navy vessels to stand by for manoeuvres.

10:30 All Navy vessels were ordered to prepare to put to sea. By 16:00 UTC, which was midnight local time, thirteen vessels were underway on a search and rescue mission for the missing aircraft.

29 July

04:11 The United States Army Transport Meigs was 103 miles west-northwest of the last known location of the missing aircraft. When the crew received a report that the shore stations had lost contact with the clipper, Meigs changed course to help with the search.

14:00 Meigs arrived at the last reported position of the Hawaii Clipper and searched the area for three hours. The transport vessel continued to search that night and the following day.

30 July

09:10 The United States Army Transport Meigs discovered an oil slick about 28 miles south-southeast of the Clipper’s last estimated position. The Hawaii Clipper carried 120 gallons of engine oil and a variety of other oils in small quantities.

The oil slick was described as somewhere between 500 to 1,500 feet in diameter and roughly circular in shape. At the time when they discovered the slick, the current was at 140 degrees at a rate of one knot per hour.

Meigs carefully searched the area around the slick and a small boat was put over the side to obtain samples of the oil; however as night was falling they were only able to collect limited samples. They stayed in the area that night, planning to pick up the slick in the morning and collect more samples.

At daylight on the 31st of July, they attempted to relocate it, thinking that the ship and the oil slick would have drifted the same distance in the night. However, there was no sign of the oil slick.

07:18 (15:18 Manila time) They were unable to find any trace of the oil slick from the previous evening. Meigs returned to the original location and continued the search in that area.

The transport ship was joined by Navy destroyers and submarines as well as Army and Navy aircraft. They searched the ocean, the island shores and the interior areas of Philippine islands Luzon and Mindana, which include large areas of tropical jungles and mountain ranges over 7,000 feet.

An inhabitant of the island of Lahuy reported that he heard a large airplane flying above the clouds around 3pm Manila time on the 29th. The weather on the island that day was overcast with a cloud ceiling of 2,500 feet.

There were no military or private aircraft reported in that vicinity on that date. An aerial search was made of the island and nearby sea.

The wind was quiet and the sea was calm. They hoped to find oil or wreckage that had floated to the surface.

They found no sign of the lost aircraft.

5th August

With still no sign of the Hawaii Clipper, the search was abandoned.

The oil collected from the slick the first evening was split into two jars. The amount collected was so small that the two samples were made up of less than 3 cc’s each; not enough to analyse in depth. However, chemists investigated the properties of the samples and concluded that the oil recovered did not come from the engines of the Hawaii Clipper.

The only remaining lead was the report that the aircraft flew low over the island of Lahuy. The aerial search showed no trace but with the mountainous terrain and jungle, it could be that the wreck was hidden in the landscape. Pan American Airways Company offered a reward for any information regarding the Clipper, in hopes of encouraging land searches in the area.

The official report by the Civil Aeronautics Authority was unable to determine the probable cause.

In conclusion, it appears that the only definite facts established up to the present time, are that between 0411 and 0412 G.C.T on July 29, 1938 was a failure of communication between the ground and the Clippers; Communication was not thereafter reestablished; and that no trace of the flying boat has since been discovered. A number of theories have been advanced as to the possible basic cause of or reason for the disappearance of the Clipper. The Board has considered each of them. Some have not been disproved, either or have been contradicted by the known facts. However, the Investigating Board feels that this report cannot properly include a discussion of conjection unsupported by developed facts. The Board, therefore, respectfully submit this report with the thought that additional evidence may yet be discovered and the investigation completed at that time.

No one ever claimed the reward offered by Pan American. No trace of the aircraft wreckage has ever been reported. Rumours abounded, as they do when there’s no evidence to be found. It had been only a year since Amelia Earhart had disappeared in the same waters.

Some said that a Chinese-American restaurateur Choy Wah-Sun was transporting three million US dollars collected by the Chinese War Relief Committee. I checked the passenger manifest and certainly a passenger of that name was onboard, but there’s no information publicly available that he was transporting cash. An unresourced website about the crash says that he owned three restaurants where the most successful was called the China Clipper, which seems a rather odd coincidence.

Others took the static in the last transmission as proof that the aircraft had flown into an electrical storm and was struck by lightning. In 1963, Pam Am flight 214, the Boeing 707 Stratoliner nicknamed Clipper Tradewind disintegrated after a lightning strike ignited the flammable fuel vapours inside the left reserve fuel tank, which led to the centre and right reserve fuel tanks exploding.

A popular theory with the media was that Japanese agents had slipped into the Clipper’s baggage compartment on Guam. The theory goes that they took control of the aircraft mid-flight and hijacked it to an island in Japanese territory, where the crew and passengers were killed and the aircraft hidden in concrete structures. No evidence has ever been found to support this and no one involved with the flight or the investigation believes that it could be true.

New research has concluded that the testing of the oil found by the United States Army Transport Meigs may not have been reliable and, based on the information noted, the oil spill may have come from the Hawaii Clipper after all.

The Meigs was sunk by Japanese bombers four years later and the underwater wreck is now a popular dive site.

Proofreading: put to see => should be “sea”.

Great write-up, as normal. Thanks!

OMG! Thank you for that; I’m so embarrassed. Fixed.

Sylvia, I committed an affect/effect slip a week ago (commenting at The Register, where I had my first introduction to your writing).

There is much grace.

Affect/effect is one I always have to think about, I have to admit.

“watercraft compartments” should be “watertight compartments”

“Lift rafts” should surely be “life rafts”?

Clearly I am having a bad day. I’ve corrected “lift rafts” to life rafts.

Watercraft compartments is more complicated. That phrasing isn’t familiar to me but it came from a primary source, which is why I noted that they were watertight. It was a diagram of the M-130 specifically showing how safe the aircraft was if it had to land on the water. I didn’t include it because the site hosting it didn’t have any provenance for the image (thus I couldn’t determine the rights to use it) and now I can’t find it. I’ll take a look to see if there’s a copy elsewhere, or else I’ll rewrite that bit.

Thanks!

An interesting final note which I only spotted today on https://lostclipper.com/2016/01/04/1919/

Apparently, some of the MH370 law suits filed are based on “Choy v. Pan-Am World Airways” in 1941!

Check out: http://www.lostclipper.com for the latest efforts on searching for the Hawaii Clipper.

Thanks! I linked the site above; it’s full of interesting information. :)

There is no such term as “knots per hour”. Ships and aircraft use nautical miles for navigation. A “knot” is defined as one nautical mile per hour. A knot is already a unit of velocity; it is incorrect to say “knots per hour”.

True, however I think that poor navigator/radio operator is unlikely to care at this stage.

Well, “knots per hour” COULD be a valid term if one were talking about units of acceleration (just being pedantic here!).

Fantastic research. I’m part of a small team travelling to Micronesia in February looking for evidence. I’d like to contact you about your research at some point!

Hi, is there a site on the web that I can find a crew and passenger list?

The fact that two large but empty crates were put on the Clipper in San Francisco for shipment to the Far East , makes for a sound plan that gives the two Japanese agents a place to hide after sneaking aboard the plane in Guam.

A 2024 guest post on this incident is at https://fearoflanding.com/history/the-disappearance-of-the-hawaii-clipper-may-not-be-as-mysterious-as-was-thought/ .