The Mount Erebus Disaster

On the 28th of November 1979, a sight-seeing flight to Antartica crashed into Mount Erebus, killing all 257 on board. The Mount Erebus Disaster, as it came to be known, is famous not just for the tragic accident, New Zealand’s worst peacetime disaster, but also because the final accident report’s conclusion was overturned within a year.

Air New Zealand flight 901 was an all-day sight-seeing trip departing Auckland at 08:00 and then landing at Christchurch at 19:00 for refuelling before returning the passengers to Auckland at 21:00, 13 hours after departure. The flight included an experienced Antarctic guide to explain the sights over the public address system. Sir Edmund Hillary had been a guide on previous flights and had been scheduled for the 28th of November flight but cancelled in favour of a speaking tour in the US. Hillary’s friend Peter Mulgrew, a New Zealand mountaineer and yachtsman, filled in for Hillary as the commentator for the flight.

The passengers were offered a champagne breakfast and three films about the Antarctic as they made their way south. The flight was due to arrive over Antarctica shortly after noon NZST.

Neither of the pilots had ever flown to Antartica before and the flight engineer had only been there once. The flight descended over McMurdo Sound for a view of Mount Erebus and McMurdo Station. These sight-seeing flights regularly descended below the minimum safe altitude of 16,000 feet so that the passengers could gain a better view and take photographs.

Air Traffic Control at McMurdo Station (Mac Centre) was aware of this and the controller advised the flight that once the flight was within radar range, about 40 miles (65 km) from the station, the flight could descend safely down to 1,500 feet using the radar controlled let-down service. The crew reported in at 43 miles from the station and asked for approval to descend further, confirming that they had clear visibility. The controller approved this and asked the flight crew to keep Mac Centre advised of their altitude. The crew reported at 13,000 feet and at 10,000 feet.

The controller asked if they still needed the radar-controlled let-down below 10,000 feet through the cloud. The crew replied that they were clear of cloud and happy to proceed visually to McMurdo Station.

However, the flight plan had been changed before the flight to fix a mistake in the earlier route. No one had informed the flight crew of the change and ATC were not aware. As a result of being on a different route, the aircraft never appeared on the controller’s radar.

The flight crew reported at 6,000 feet and reported that they were still visual and descending to 2,000 feet. They still believed they were flying west of Mount Erebus and were safely over water when they crashed into the mountain.

The DC-10 was not understood to be lost until hours later, when flight 901 failed to arrive at Christchurch. The search and rescue teams were initially searching the assumed flight path for hours. Finally at midnight, a US Navy Lockheed LC-130 Hercules spotted the wreckage on Mount Erebus. The weather was too poor for a landing but another helicopter circled the wreckage to confirm the Air New Zealand logo on the tail and that there was no sign of survivors.

The following morning, three mountaineers were lowered onto the Mount Erebus slope from a US Navy UH-1N helicopter. They confirmed that all passengers and crew had been killed in the impact. Recovery and investigation parties were taken to the site in a Royal New Zealand Air Force C-130. The mountaineers returned to the crash site where they erected polar tents and left caches of food and equipment for the parties.

A helicopter pad was established and the longer task of recovering bodies and personal belongings was begun. The site was laid out into a grid system for a detailed accounting of the wreckage. The investigations team were able to retrieve both the cockpit voice recorder and the flight data recorder with the support of mountaineer support from the Face Rescue Squad.

The final report now known as the “Chippindale Report” after chief investigator Ron Chippindale, was released in May 1980.

This final report acknowledged the change in flight plan but concluded that the principal cause of the crash was pilot error, specifically:

The decision of the Captain to continue the flight at low level toward an area of poor surface and horizon definition when the crew was not certain of their position.

The government had already decided to hold an inquiry in March, two months before Chippindale had completed his report. Despite this, they made the report public in June, leading to headlines blaming the incompetent crew for the deaths of the sight-seeing passengers. At the same time, it had become public knowledge that the flight coordinates had been altered without the crew’s knowledge. The airline countered that if the pilots had remained above the minimum safe altitude set for the flight, the plane would never have crashed.

One damning point was that the report did not stick to the official cockpit voice recorder transcript, which had been transcribed by CVR specialists with support from the NTSB. Instead, the report consistently referred to an unofficial transcript from the cockpit voice recorder, in which ambiguous and hard-to-decipher interactions were replaced by specific statements, all of which supported the conclusion of the report.

The differences included a key phrase of “Bit thick here, eh Bert?” which the report referred to as showing that they were flying in cloud, as opposed to the CVR specialists who believed that the flight crew member said “This is Cape Bird” as he recognised a landmark out the window. The audio was not clear enough to be sure and on the official transcripts it was marked as unintelligible. However, in the final report, the transcript quotes the flight engineer as saying “Bit thick here, eh Bert” as a fact, with no reference to the audio difficulties or differing interpretations.

Also, there was no one who went by the name “Bert” on the flight deck.

On the 7th of July, a Royal Commission of Inquiry began to examine every detail of the accident, which provided much new insight both into the crash and the investigation. This report is known as the Mahon Report, after Hon. Justice Peter Mahon who presided over the inquiry with the support of two barristers. He was was given a number of points to investigate, including whether any “culpable act” had directly led to the disaster.

Judge Mahon did not have an aviation background but he went to great lengths to understand the key issues of the flight, including the navigation system for the DC-10 and the process of creating a transcript from a cockpit voice recorder.

His shocking conclusion was that the airline had decided in advance that the cause of the accident must be attributed to pilot error.

The palpably false sections of evidence which I heard could not have been the result of mistake, or faulty recollection. They originated, I am compelled to say, in a pre-determined plan of deception. They were very clearly part of an attempt to conceal a series of disastrous administrative blunders and so… I am forced reluctantly to say that I had to listen to an orchestrated litany of lies.

He was less harsh about Chief Inspector Chippindale but nevertheless dismisses his findings as untenable. He also educated himself about the illusion known as “whiteout”, a circumstance which had not been investigated in the original report. The Mahon Report included in-depth explanations of all of these components so that the detailed analysis is also extremely accessible, even without aviation experience.

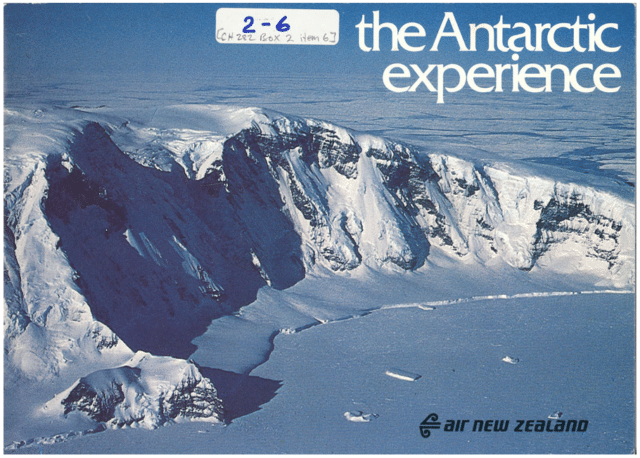

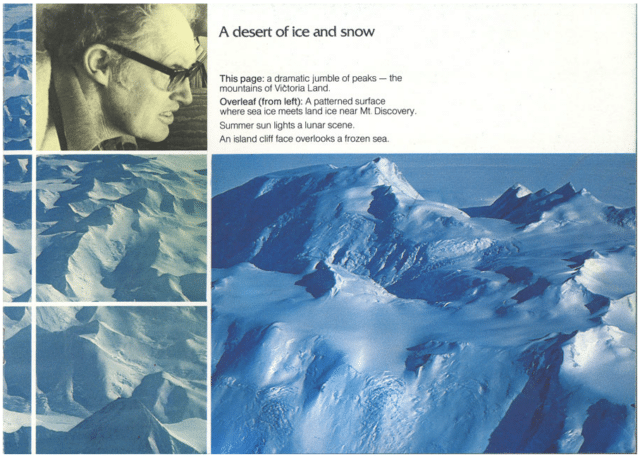

Although Chippindale concluded that the principal cause of the crash was the flight crew’s decision to fly beneath the minimum safe altitude, Judge Mahon showed that this was routine for these sight seeing flights and indeed, the promotional brochure showed photographs which were clearly taken from below the minimum safe altitude.

Judge Mahon concluded that the crash of Air New Zealand flight 901 was down to ten separate issues, where removing any single one would have avoided disaster.

Of these ten contributing causes, he determined that only two of them were the result of a culpable act or omission.

- There was not supplied to Captain Collins, either in the RCU briefing or on the morning of the flight, any topographical map upon which had been drawn the track along which the computer system would navigate the aircraft.

Neither Captain Collins nor any other member of his crew was told of the alteration which had been made to the computer track.

He believed that the principal cause was Air New Zealand’s decision to change the flight plan waypoint coordinates without advising the crew. This new flight plan took the aircraft directly over the mountain rather than alongside it. The crew believed that they could descend safely based on the track that they believed they were following. In addition, weather conditions most likely lead to whiteout conditions, which meant that there were no navigational references visible to the flight crew. Although they were in clear weather, they were unable to see the mountain, even when it was directly in front of them.

The dominant cause of the disaster was the act of the airline in changing the computer track of the aircraft without telling the aircrew. That blend of act and omission acquires its status as the “dominant” cause because it was the one factor which continued to operate from the time before the aircraft left New Zealand until the time when it struck the slopes of Mt. Erebus. It is clear that this dominant factor would still not have resulted in disaster had it not been for the coincidental occurrence of the whiteout phenomenon. But the conditions of visual illusion existing in Lewis Bay would have had no effect on flight TE 901 had the nav track of the aircraft not been changed, for it was only the alteration to the nav track which brought the aircraft into Lewis Bay instead of McMurdo Sound.

In my opinion therefore, the single dominant and effective cause of the disaster was the mistake made by those airline officials who programmed the aircraft to fly directly at Mt. Erebus and omitted to tell the aircrew. That mistake is directly attributable, not so much to the persons who made it, but to the incompetent administrative airline procedures which made the mistake possible.

The Mahon Report, with its emphases on detail and understanding technical aspects, changed the way we look at risk management and organisational failures. He paved the way for investigations to insist on taking on the complex issues rather than allowing an investigation to quickly settle on an easy answer and look for evidence to back it up.

The Erebus: The Loss of TE901 website is a fantastic resource that goes over the accident and both reports, along with the context in which they were written. I highly recommend taking a few hours to go over the rich collection of information and explanations that has been collected there.

Sylvia, I have these accident and investigation reports and both books on Erebus. I remember the long, long wait while the news told us of first the ‘overdue’ and finally the crash.

I was in the RNZAF at the time and knew one of the crew. He was an RNZAF Navigator who had trained as a pilot to join Air NZ. He was not in the cockpit at the time of the letdown and crash. I’m very confident that, had he been, he would have been plotting their ground track on a map and there would have been no accident. It is ironic that, throughout the flight, an instrument on the panel was quietly reading out Lat/Long and was not referred to.

I have no problem with the various ‘Coverup’ conclusions of the report. However, although I’m an engineer, I discussed the accident with my experienced pilot friends. Their unanimous conclusion was that if you fly a perfectly serviceable aircraft into a hill, when you have the means of accurately determining your position available to you, it’s your fault.

There will never be agreement on this. However, that was the view at the time.

Yes, it’s not quite black and white. For me, the mitigating factor is that they were confident that they knew where they were. If you are unsure of your location, then sure, you are responsible for taking extra precautions.

Very interesting article, thank you Sylvia. It’s not often that I hear the word, “Honorable,” before a judge’s name and don’t cringe, but this man truly deserved the honorific.

Sylvia

This is a complicated story, and once again you have done an excellent job of distilling it into an absorbing narrative.

Like David P, I recall the long wait as the status of this flight changed from ‘no communication’, through hoping it might be diverting to Dunedin (closer to Antarctica than Christchurch is) until finally ‘fuel exhausted’. Without the instant updates we have access to now, the story was told through hourly radio news bulletins.

The Mahon report highlighted the significance of whiteout conditions. Only by being in a whiteout once (walking on a mountain, not flying) did I realise what this meant. It’s not that you can’t see your hand in front of your face, as there might be reasonable visibility. But with ground and air both the same shade of white, and with diffuse light, there is no horizon and no depth perception.

Mahon’s assertion that he had been subjected to an “orchestrated litany of lies” was ruled by the Court of Appeal to be both substantially invalid and outside the jurisdiction of his inquiry. On appeal to the Privy Council, the Court of Appeal’s finding remained as the Privy Council found no evidence of “concerted attempts to deceive anyone”.

Despite that overreach, Mahon made a significant contribution to the investigation of aviation accidents, in laying the ground for a much more multifaceted and multidisciplinary approach.

Is it appropriate to call this the ‘Mount Erebus disaster’? The aircraft flew into terrain just below 1,500 ft ASL. The fact that there was a further 11,000 ft of mountain rearing up ahead of them is, in some ways, irrelevant. The aircraft would have hit rolling hills if it had been in another location.

A couple of other points. There was no-one in the flight crew called ‘Bert’, but with frequent visitors to the cockpit it’s probably hard to be certain that there was no-one by that name on the flight deck at the time of the recording. And, sorry, I have to say this: principal, not principle.

Again, a great account. Thanks very much.

Andrew

I didn’t expect any comments defending the mountain but i do take your point! And I’ve fixed principal, thank you!

Your score is still 1 out of 3 in that respect.

3/3.

0/3 now, actually.

(Sorry, I temporarily don’t have access to my email.)

Haha arrrrgh. OK, now definitely 3/3; I was definitely on the wrong scoreboard there.

James Reason, British human factors researcher, divides accidents into two categories. One type result from the action of the people which he terms ‘individual accidents’ and the other ‘organizational accidents’ which results largely from the actions of Organizations and their managers. Performance of sharp end workers (aircrew, ATC controllers, Technicians) is shaped by the work place conditions and upstream organizational factors. Operators, located at the ‘sharp end’ of a system, commit what he calls ‘active errors’ that directly lead to accidents. Operators’ active errors are influenced, James Reason argues, by Organizational errors which are latent in nature and lie hidden within the system. Latent errors are potentially accident waiting to happen and are present in the system well before an accident. Latent failures set the stage for the accident, while active failures tend to be the catalyst for the accident. The source of latent errors mostly lies with the higher decision and policy makers. It’s widely believed that errors are the logical consequences of antecedents or precursors that had been present in the systems.

Justice Mahon did a path braking investigation which (probably for the first time) not only brought the Organization within the realm of investigation but went on to squarely blame them. He brought out, correctly that low flying (below safety height) was routine and in fact it was publicized all over. The very nature of flight (sight seeing) would put pressure on the crew to give a good viewing experience to the passengers who had payed a fortune.

Regarding the ‘litany of lies’ IMHO he was absolutely correct. It was a typical organizational accident.

From wikipedia:

A GPWS would’ve really helped here. (A quick glance at the radar altimeter in time would’ve also helped them, but why would you look there if you believe you’re over open water?)

https://www.erebus.co.nz/Background/The-Flight-Path-Controversy explains how the flight path error originated, and why nobody detected it. The captain actually did plot the flight path on a map before the flight, but unfortunately that was off the older flight path through McMurdo sound that had been in effect for 14 months; the altered computer printout that he received for that flight led across Mt. Erebus. Flying into the bay, it looked like they were flying through McMurdo sound, because the coast and mountain ahead of them was hidden in sector whiteout. (The page has a map showing the similarities.)

The CVR transcript shows that they did have GPWS, and that it activated 4 seconds ahead of the crash, at 500 ft. — not enough time for the pilots to understand the situation and save the aircraft.

That’s a very good point. Considering how new the technology was, I really should have included that.

FE isn’t part of the flight crew?

Oh eek! Sorry to all the flight engineers; that was a last minute edit that clearly went terribly wrong.

This is indeed a sorry tale. I spent 35 years as a fast-jet pilot in the RAF and came across this type of accident many times sadly. I also conducted 2 Boards of Enquiry whilst serving. In the bad old days the search for who was to blame was the normal practice. Thankfully this is no longer the case. Aircraft accident investigators in the Uk no longer search for who was to blame and simply conclude in findings on the relevant facts of the case and make recommendations for the future thus learning lessons to ensure that, as far as is possible, that it doesn’t happen again. The Hunter accident at Shoreham in August 2015 is a good example. The AAIB report https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/58b9247740f0b67ec80000fc/AAR_1-2017_G-BXFI.pdf states the facts and left the appropriate authorities to decide on future action. The local police force carried out an investigation and brought a prosecution for manslaughter but crucially they were denied access to much of the evidence gained by the AAIB. This aspect is critical to preserve the independence of the investigating authority and their quest to find out what went wrong not WHO did something wrong and was to blame. This is also important for those being investigated, encouraging openness and a willingness to cooperate in the knowledge that any evidence they give will not be used against them in criminal proceedings. Interesting, the pilot of the Hunter was found not guilty on all charges.

This crew descended legally below minimum safe altitude VMC – the fact that the flight plan had been altered (unknown to the crew) is relevant and a key finding, but in my view not the root cause of the accident. The crew appeared to carry out their descent safely and with professionalism maintaining VMC. As they were VMC (or so they thought) this allowed them to continue to operate the aircraft at low level safely. Sadly unknown to them, they were experiencing whiteout whilst heading directly towards the mountain and without this phenomena the accident would not have happened. It was the final link in the chain which had it been broken we wouldn’t have been having this sad discussion. I have experience of numerous mid-air collisions where the human eye simply cannot detect another rapidly closing small aircraft if it remains on a constant vector through the cockpit windscreen. This is widely acknowledged and used in mitigation. Whiteout effects on the eye is another one of those human eye visual issues over which we have no control and one in which pilots need special awareness. Fortunately today we do.

The Hunter accident really is a good example of this. I’m still very proud of the AAIB for standing their ground.

David Provan: the case of William Glen Stewart (see link below) is one of the demonstrations of how an air captain’s judgment is constrained by bonus-counters at headquarters. This is an even worse case: what would the captain have done if he found that the track programmed into the system wasn’t taking him where he expected (if he had done enough prep and/or had enough charts to know what to expect)? If the track disagreed with the nav computer, which should he believe? For that matter, why did ANZ send out two pilots who had never been on this route before? ANZ advertised the plane’s dangerous flying (although of course they didn’t call it dangerous); they shouldn’t have assigned someone as captain who hadn’t flown that route several times before in the right seat(*), and if it was his first time in left seat he should have had someone experienced as copilot(**).

I’m also wondering about a 13-hour flight with (apparently) one crew; I don’t think that would be legal today, and ISTM it’s a bad idea in any case given the hazardous flying after several hours en route.

(*) In the early days of Mississippi riverboating, pilots who had not had a job recently would hitch a ride in order to “look at the river”; the free meals would have been an incentive, but it would also be a professional need in the era before the pilots formed a union that set up the equivalent of PIREPs to give each other current information about a notoriously changeable river. The Antarctic doesn’t change, but sending a green crew on a dangerous flight sounds almost as hazardous as putting an unsupervised “cub” in charge of a riverboat.

(**) There was widespread amusement in the US a couple of decades ago when a pilot was misreported as being charged with landing at an airport he’d never landed at before. Obviously there’s a first time for everything; IIRC the real charge was that he hadn’t landed there under supervision before going in as PiC. The larger problem was that he’d landed at the wrong airport, but that was the reported charge; ISTM that stunting in a passenger plane should have some analogous experience requirement.

(A PDF of a detailed article about Stewart can be reached through here

There were 20 crew aboard the aircraft; this included the Captain, two first officers, and two flight engineers.

The court proceedings establish clearly that the Captain did a thorough flight prep at home on the day before the flight, plotting the complete (but outdated, unbeknownst to him) course on charts and an atlas, and that he took all of these maps with him on the flight. You really need to read about the flight path controversy (I linked that earlier) to understand that the crew matched what they saw to what they thought their route was, and that not even the experienced commentator who acted as a guide for the passengers found anything amiss. The only thing the crew did not see, because it was hidden in the sector whiteout, was the mountain.

For the PDF you linked, a shorter version without google secrets works for me: http://picma.info/sites/default/files/Documents/Events/November%20Oscar%20article.pdf

Sadly, that story ends with the suicide of the pilot.

I hope you don’t mind, I edited your link to make it a bit shorter.

My only experience with winter weather is VFR in Europe. I don’t feel competent to comment, except to praise the judge whose very competent and unbiased investigation put the blame where it belonged, and cleared the names of the flight crew.

May they rest in peace.

Good afternoon (morning/evening) to all, my name is Colin McLaughlin. I’m from Chicago in the United States (U.S.). I have, in my possession, both Chief Inspector Chippindale’s & Justice Mahon’s reports on Erebus in PERFECT CONDITION. I was absolutely OUTRAGED when Air NZ never told Captain Collins of the change to the McMurdo waypoint coordinates. Telling flight crews of ANY changes to the flight plan whatsoever is ESSENTIAL. Also, the briefing NEGLECTED to inform flight crews flying down to the Antarctic, of the dangers of whiteout. Finally, (and most controversially), Chippindale made up lines in the OFFICIAL CVR (Cockpit Voice Recorder) transcript, lines like: Bit thick here, eh Bert? & You’re really a long while on instruments this time are you? These were NEVER even said on the CVR in the FIRST PLACE. May all 237 passengers & 20 crew on TE 901 Rest In Peace…