The Last Flight of B121-120

The Beagle B.121 Pup is a British, single-engine, all-metal aircraft produced in the 1960s.

British Executive and General Aviation Limited, who traded as BEAGLE, designed the Beagle B.121 Pup as a replacement for aging Tiger Moths and Pipers; Beagle Aircraft Limited marketed it as “a pilot’s aeroplane”. I found the designation B.121 interesting. B stands for Beagle and the first digit defined the number of engines. The second two digits were to show the series, where odd was for single-engined aircraft and even for twins.

The two-seater, single-engine aircraft was popular in flying schools in the UK and Europe, whereas in the US the Cessna 150 and 172 and the Piper Cherokee were filling the same role as training aircraft. Unfortunately, the company had burned through over a large amount of capital before the B.121 Pup was produced and was unable to continue, despite finally finding success. The government refused a plea for a further £6 million for further development and the company went into receivership in 1967. The full history can be read on British Aviation – Projects to Production.

Only 226 Beagle Pups were produced and of that, only 176 delivered, with the remaining 50 used for components.

This is the story of how one Beagle Pup, B121-120, was lost.

It was a crisp Thursday afternoon in late October at the flying school. The instructor was highly qualified and the flight was routine, a training flight for a new student. They were in one of the two shiny new Beagle Pups purchased by the school just a few months earlier.

As the instructor and student departed from the grass runway, the engine ran rough and then backfired; a bad sign.

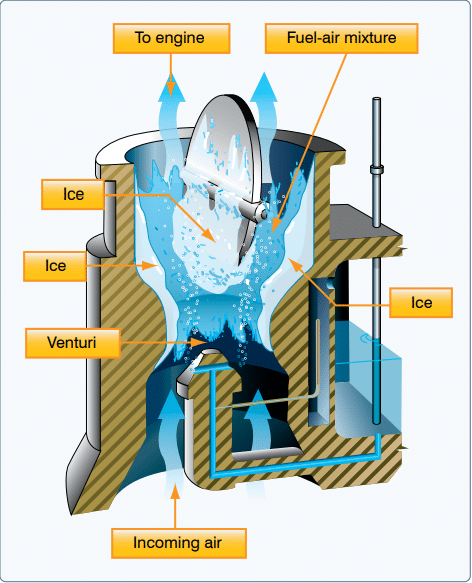

The rough engine and a reduction in power are clear symptoms of carburettor icing: vaporising fuel and a decrease in air pressure cause a sharp temperature drop in the carburettor and any condensed water vapour inside the carburettor freezes. This reduces the air intake of the carburettor which has the same effect as closing the throttle.

fuel-air flow to the engine.

The Beagle Pup 100 series has a Rolls-Royce Continental O-200A engine which was more prone to carb icing because of its location in front of the engine, relatively exposed. Later models used Lycoming engines, where the carburettor is located close to the oil sump, which keeps it relatively warm.

The easiest way to clear the ice is to melt it using “carb heat”: an anti-icing system which diverts the hot exhaust onto the carburettor in order to keep the temperature above freezing. It is common to have the carb heat on when in conditions where icing is a risk. This is a trade-off as the aircraft performance suffers as the warm air is less dense; with the carb heat on, the engine will perform badly and require much more fuel.

I was trained to always set the carburettor heat ON during the downwind leg and then OFF before touch-down, so that the full power of the aircraft is available in case of a need to go-around. Since then I’ve heard this is an oddity specific to UK flight schools! However, it’s clear that a pilot would not want to take off with the carb heat on because of the reduction in power, even in icing conditions.

Now in a case like this where the engine is suddenly running rough, a pilot can turn the carb heat in order to melt it; however heating a carburettor which has already iced up takes time, which isn’t available on an engine failure shortly after take off.

The training flight had just reached 250 feet when the engine failed. The Beagle Pup was now a glider.

The flight instructor took control. There was a housing estate straight ahead of them, so the instructor turned hard right to the southwest side of the airport for the emergency landing, aiming for the grassy area near the clubhouse at the other end of the runway.

As he came around, the Pup’s wheels clipped a hedge, which shouldn’t have mattered… except that the hedge concealed a large concrete drain pipe in a ditch. The aircraft then bounced off the pipes and into the car park, where it crashed into the parked car.

Neither flight instructor nor the student were hurt; however, both the Beagle Pup and the car was written off.

The car belonged to the poor student, whose relief at being safe on the ground was no doubt mitigated by the fact the loss of his car. As Rudy put it, the car was not insured for damage sustained by landing aircraft.

For as Rudy and those who read the comments will have spotted by now, this is an analysis of an accident that happened in Rotterdam in 1970. Rudy told the story in the comments when talking about his friend, the flight instructor Nico Pilger. Fear of Landing reader Richard van de Wouw read Rudy’s comment about the (un)fortunate landing at Rotterdam and wanted to know more. Richard found the incident details on Aviation Safety Network to share with us.

The above is based on the translation of Herman Dekker’s list of incidents in 1970 and an incident report at Aviation Safety Network, with details filled in from Rudy’s memories of the incident.

The Beagle Pup, by the way, is still around somewhere in the hangars of the Dutch aviation museum, the Nationaal Luchtvaart-Themapark Aviodrome. In 1993, there was some talk of reassembling the Pup for display but sadly, so far it hasn’t happened. Maybe some day someone will put the poor Pup back together again.

The photo is clear: A Beagle Pup. I was introduced to aerobatics on the Pup, it was indeed the same flying club. I will have to see if I can find it in my logbook.

Strange, as I remember Nico – who was a good friend of mine, told me that it had been a Jodel. I cannot remember any more whether or not the Pup had an automatic carburettor de-icing control. What I do remember is that the instructor had been cleared of any wrongdoing, in fact had been congratulated on his decision to take control and move away from the housing estate.

Richard van de Wouw was also a friend of ours, so if you read this: Hello, long time, Richard. Sylvia has my email address, she is free to give it to you.

Great detective work Sylvia, Hercule Poirot would have been proud (or in your case: Miss Marple)!

In your original comment, you said it was either a Pup or a Jodel, actually. I couldn’t find any reference to it having an automatic control but then it’s hard to prove a negative :D

I loved the photo with the car.

There is no automatic carb heat on the pup. Recently did initial aerobatics training on a pup.

Sorry, your comment got caught in moderation! You are now on the approved list and your comments will go straight through in future. Thanks for the confirmation on the carb heat question!

To come back on the subject of the Beagle Pup: I still have my logbooks, could not yet part with them.

In 1969 I had joined the Rotterdam Aeroclub. Rotterdam is an airport with published instrument approaches. The club rates were very reasonable. I trained on Piper Cherokees for my instrument rating. In my logbook I have them with the registrations PH-VRY and -VRP. The “VR” in the registrations stands for “Vliegclub Rotterdam”, Rotterdam Aeroclub.

In January 1971 I did some aerobatic training in one of the club’s Beagle Pups, it was registered “PH-VRT”, so it was not the aircraft in the photo. The instructor’s name was De Wilde. Looking back, I probably was not a star at aerobatics. When I joined the Tiger Club at Redhill I had some instruction form Neil Williams on the Stampe SV4. To say that he was not impressed with my aerobatics is probably expressing it mildly. In my defence: to become really proficient in aerobatics, unless one is a pilot in the Air Force, requires frequent training and a big pocket. Although, having said that, in those days a Stampe or Tiger Moth would set a club member back by about £ 8 per hour. And in the ‘seventies the exchange rate of the £ Sterling was very low. But I had to wait for an opportunity to get to Redhill. My employer did a lot of business in the area, so I kept a Ford Cortina at Gatwick and later managed to convince my employer that it would save him a lot of money in parking fees if I brought the Cessna 310 from Gatwick to Redhill if he had an overnight stop. It was a lot cheaper, and I could park directly at the club.

Those were the days my friend !

Student survives plane wreck which totals his parked car!

Mike, I need you to write all my headlines for me!

Sylvia, you said it.

“This is a trade-off as the aircraft performance suffers as the warm air is less dense; with the carb heat on, the engine will perform badly and require much more fuel.” As I put on my former-chemist hat for a moment, this doesn’t seem right; if the air is less dense, adding fuel won’t help as there won’t be any more oxygen to burn it. (cf the way I was taught to lean fuel flow at altitude: inch it back until maximum RPM was reached, because that meant there was no unburned fuel interfering with performance.) All this is from 4-decade-old memories, so I’d be glad to hear something definitive.

It is much more likely that I haven’t understood it — chemistry is not a strong point! I have heard of putting carb heat on for taxi-ing; I was never taught to do so, although making sure it is off is part of the pre-take-off checklist in a Cessna, presumably for exactly this reason.

Looking at where I found the image, there’s a bit about this: https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/handbooks_manuals/aviation/phak/media/09_phak_ch7.pdf

The use of carburetor heat causes a decrease in engine power, sometimes up to 15 percent, because the heated air is less dense than the outside air that had been entering

the engine. This enriches the mixture.

[…]

Since the use of carburetor heat tends to reduce the output of the engine and to increase the operating temperature, carburetor heat should not be used when full power is required

(as during takeoff) or during normal engine operation, except to check for the presence of, or to remove, carburetor ice.

Returning to the accident itself: should the pilot have had carb heat on until takeoff as a precaution? I don’t remember having to do that at my field, but (a) ancient memories, and (b) I was inland (and in an area where cool weather tended to come from dry north winds) rather than on the coast.

I’m also wondering about an insurance company refusing to cover damage from any dropped object, even an unnatural one. (Natural ones were certainly covered around here a few ones ago, when all the auto body shops were fully booked because of the results of a hailstorm.) Would they have declined (e.g.) the possibly-legendary impact of ice from a leaky valve for an onboard toilet?