Goddamned Cat

Sometimes the best stories are the ones that aren’t so famous, where the race was not won and the record was not broken. This is such a story. It’s the story of a cat, who was neither the first cat to fly nor the first cat to cross the Atlantic. But the cat rubbed shoulders with heroes who helped to make aviation what it is today. And the cat is at least famous for one thing: he was the subject of what was probably the very first in-flight radio transmission.

Roy, come and get this goddamned cat.

The speaker was Melvin Vaniman and he was the engineer of Walter Wellman’s airship America which had just launched in an attempt to cross the Atlantic. Roy was Wellman’s secretary, safe on land and out of the way of the panicking cat.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

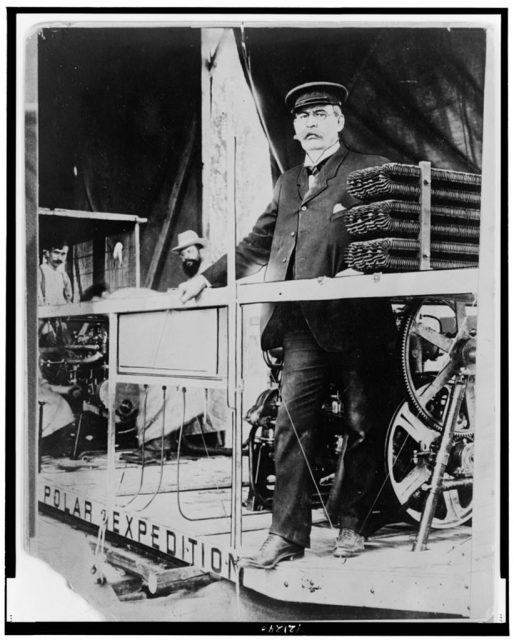

Walter Wellman, a journalist, explorer and aeronaut, was a fascinating man. At age 14, he published a weekly newspaper in his home town. By age 21 he took it a step further: in 1881 he established the Cincinnati Evening Post, a popular investigative newspaper which continued publication until the end of 2007. In 1894, Wellman led a polar expedition by boat and sledge from Svalbard in an attempt to be the first to reach the North Pole but only made it as far as the 81st parallel.

It was at this point that he is said to have first considered an aerial attempt at the North Pole; however he concluded that balloon technology did not offer the steering and propulsion that he needed. He led a second polar expedition in 1898, again by ground, this time reaching the 82nd parallel. It was ten years after his first thought of an aerial crossing when he discovered that recent innovations in France might offer the solution he was looking for. He began to look into the possibility of reaching the North Pole by dirigible.

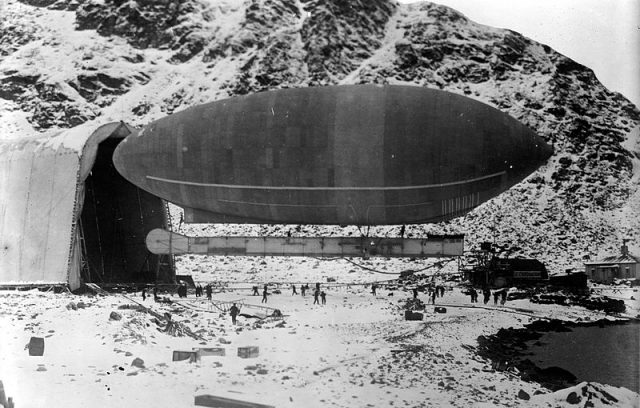

He was quickly convinced and, on the 31st of December 1905, Wellman announced his intention to fly an airship to the North Pole. The America was constructed in Paris the following year: a non-rigid airship 50 metres (165 feet) long and 15.8 metres (52 feet) wide at its greatest diameter, carrying 7,300 m3 (258,000 cubic feet) of hydrogen in its fabric and rubber envelope. It had three internal-combustion engines, two propellers (one fore and one aft) and a gondola which could hold a crew of five.

A hangar for the dirigible was constructed in Spitsbergen on Danes Island, Svalbard, which borders the Arctic Ocean. America was delivered by ship to Spitsbergen in July 1906, just six months after Wellman’s announcement.

However, when Wellman and his team attempted to erect the airship, the engines “self-destructed”. America was dismantled and sent back to Paris. In June 1907, the airship returned to Spitsbergen, this time with a new centre section increasing both its length and volume. This time, the airship was erected correctly but Wellman and his team were forced to wait out bad weather and it wasn’t until the 2nd of September that America was safe to pull out of the hanger. Wellman launched America the same day, along with mechanic Melvin Vaniman and navigator Felix Reisenberg.

Melvin Vaniman, an adventurer and businessman nicknamed The Acrobatic Photographer, was a enthusiastic and competent aviator and balloonist. He is best known for his panorama of Sydney, shot from a hot air balloon in 1903, using a self-constructed “swing-lens” camera. In 1904, he appears to gave given up photographery and taken up exploration.

The trip was not a success. They encountered bad weather and were forced to turn back after travelling only a few kilometers. The America had taken damage in the storm and was deflated and sent back to France for repairs.

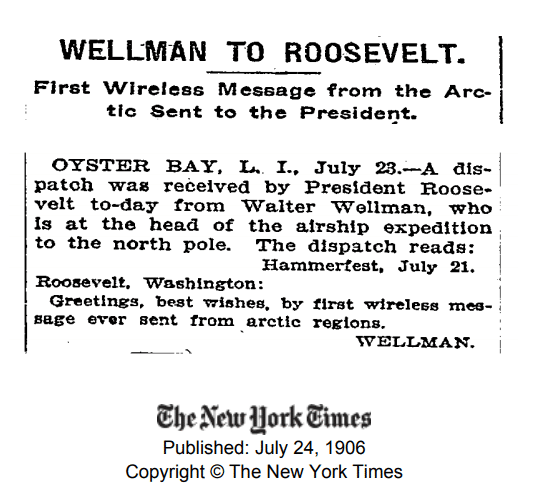

The crew did achieve one first: the first wireless message from the Arctic. The New York Times reports that on the 23rd of July, 1906, President Roosevelt received a dispatch:

In July 1909, Wellmann, Vaniman and two others made another attempt to reach the North Pole but again they encountered difficulties. They’d travelled 100km (60 miles) north of Svalbard over the course of three hours when they suffered a mechanical failure which caused the America to go into an uncontrolled climb.

They vented hydrogen to regain control of the airship at 5,000 feet, coming down to be rescued by a Norwegian steamer.

Wellmann immediately began planning a third expedition but cancelled it wihen the news broke that the North Pole had already been reached.

Dr Frederic Cook, along with two Inuiit men, declared that they had reached the North Pole while they were cut off and stranded for 14 months from 1907 to 1908.

At the same time, Robert Peary, claimed to have reached the North Pole in April 1909 and said that he didn’t believe that Cook had actually made it there. He launched a campaign to discredit Cook’s trip. Dr Cook was expelled from the Explorers Club when the Copenhagen University rejected his proof of having reached the North Pole. In 1910, the New York Times called him “one of the boldest fakers the world has ever known”.

It is still not clear if either of the men (or for that matter Richard Byrd in 1926) actually reached the North Pole. Certainly, the first undisputed explorers who can be verified as having reached the North Pole were Roald Amundsen and his 15 crew in the airship Norge.

But that’s a different story. We’re not here to unravel the discovery of the North Pole other than to understand why Wellmann, in 1909, dropped his aspiration to be the first.

He found a new goal, one that used both his dirigible and his wireless: he wanted to make the first aerial crossing of the Atlantic. His friend Melvin Vaniman was again up for the challenge and joined as the airship’s engineer. They also took a radio operator, two mechanics and a navigator, who was named Murray Simon. Simon was a 29-year-old junior officer serving on the HMS Oceanic. He was given special permission to take leave and join the America as its navigator.

The America was enlarged again for the longer journey. The cotton and silk balloon now had an enclosed area at the bottom, called the ‘car’, which held the engines and crew. At the rear of the car was the rudder and there was a wheel at the front. Underneath the car was a lifeboat and a large metal tail (equilibrator) which trailed 300 feet behind the airship. A spark gap radio set was installed on the life boat.

Spark-gap transmitters were used for radio (wireless telegraphy) from 1887 to 1916, generating radio frequency electromagnetic waves. This was done with a spark gap: two conducting electrodes separated by a gap usually filled with a gas such as air, designed to allow an electric spark to pass between the conductors.

I have to say, this is not a system one would think of as optimal for an airship filled with hydrogen. However, this radio built into the America successfully made many of the first aerial transmissions, including the first in-flight transmission and the first emergency call.

The airship hangar had two residents, stray cats which had made their home there. One was killed by a wolfhound and the other, Kiddo, became the crew’s mascot.

Simon the navigator had his share of naval traditions, one of which was that a ship needs a cat and so when the day finally came for them to start their trip, he reportedly picked up they grey tabby and tossed it into the lifeboat.

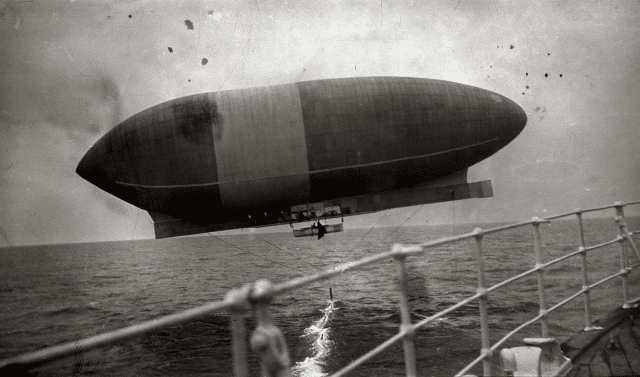

America departed Atlantic City on the 15th of October 1910 amid much excitement. Simon wrote in his log that it was time to “make those blooming critics eat their words”. They were towed out to sea and then ascended up into a fog bank.

Kiddo was less impressed. He began to howl pitifully and rushed around the lifeboat “like a squirrel in a cage”. Vaniman, attempting to share the lifeboat with the demon cat, sent that famous message to Wellman’s secretary who was at the shore: “Roy, come and get this goddamn cat.”

Vaniman wanted to get rid of the cat, immediately. Simon refused, saying if it was bad luck to have a ship without a cat, it was even worse luck to let a cat leave a ship. Not to mention that if a ship’s cat fell or was thrown overboard, it would summon a terrible storm to sink the ship.

They went to Wellman with the dilemma, but he refused to make a decision. He told Vaniman to do as he liked about it. Vaniman trapped the cat in a canvas bag to lower it down to the motor launch which was still travelling underneath the airship. Kiddo was lowered down to just above the waves, or possibly dunked just below them, while the boat attempted to recover him. The sea was too rough and they were unable to reach the bag, so Vaniman had it hauled back up again.

Kiddo the cat was now committed to the attempt to cross the Atlantic. To the relief of everyone, he soon gained his airlegs and behaved fairly well once he was allowed out of the bag.

Kiddo was not the first airborne cat, as it happens. In 1785, Vincenzo Lunardi, known as The Daredevel Aeronaut, took a dog, a cat and a caged pigeon up in a hydrogen-filled hot air balloon for a demonstration in London. But he was undoubtedly the first to make an aerial journel of any distance.

Simon continued to defend his choice to bring the cat in the ships logs.

You must never cross the Atlantic in an airship without a cat. He is sitting on the sail of the lifeboat now as I write, washing his face in the sun: a pleasant picture of feline contentment. This cat has always indicated trouble well ahead. Two or three times when we thought we were “all in” he gave most decided indications that he knew we would be shortly getting it in the neck.

He said that Kiddo “howled piteously, I never heard a cat make such a noise,” when they encountered rough weather or when the dirigible lost height, which seems reasonable under the circumstances.

The terrible storm came (despite Simon keeping the cat on the ship) sending the dirigible off course. Then the engines failed at 38 hours into the flight, and there was no way to repair them in flight. Somewhere between New York and Bermuda, the America began drifting without power. The crew jettisoned all excess weight, although thankfully not the cat, as the airship floated south.

They drifted for a further 33 hours when they finally spotted help: the lights of the Royal Mail steamship Trent were visible in the distance. How to attract its attention?

Wellman himself told the story for the New York Times.

Mr Vaniman poured gasoline upon some waste, hooked the ball upon a wire, and, lighting it, let the blazing mass far down below the airship. It must have been a strange scene which presented istelf to the eyes of the officers of the Trent — a huge but graceful airship floating through the dim light, and underneath it a glazing signal for attention. Now the Trent change her course and came nearer, in response to our summons.

Once they knew they had the Trent’s attention, they sent morse code using a signalling lamp and then contacted the ship’s crew directly using the radio to make their predicament clear. They may not have managed to cross the Atlantic but they had achieved another first: the first aerial distress call by radio.

The stranded crew, including Kiddo, got into the life boat. They opened the gas valves on the airship and then dropped the lifeboat away, landing in the water near the Trent. The airship drifted up and out of sight. It was never seen again.

Meanwhile, the winds were high and the Trent almost ran the lifeboat down as they tried to approach. They tried again and were able to haul the lifeboat aboard the ship. The six-man crew was safe. Kiddo the cat was found fast asleep in the aft chamber of the lifeboat. He began howling again when they removed him but settled down once the crew of the Trent brought him breakfast.

The master of the Trent sent a message to New York confirming the rescue of the ‘crew and cat’:

At 5 a.m. today sighted Wellman’s airship America in distress. Signaled by Morse code that he required assistance and help. After three hours’ maneuvring and fresh winds blowing, got Wellman with his entire crew and cat. Were hauled safely on board. All are well. The America was abandoned in latitude 35:43 north, longitude 68:18 west.

DOWN, Master.

He later told the press, “… I had the pleasure of welcoming aboard Mr. Wellman and his five lieutenants and a cat which seemed little the worse for its air experience.”

The New York Times countered this with gossip: “Details of the rescue that appealed to the company’s officials here was the saving by Capt. Down of the pet cat, for the Captain’s antipathy to felines is well known to his friends.”

The aerial crossing of the Atlantic had failed but Wellman’s flight did set a number of records. At 1,600 km (1,000 miles) America had travelled the most distance ever covered by a dirigible (manned, one would assume), along with the longest airship trip in time, the first radio message from an airship to shore, the first radio message from an airship to a ship and the first rescue of an airship crew at sea.

The New York Times wrote:

…Mr. Wellman, who is not daunted by the failure of this first experiment, says that “probably a larger and stronger air craft can be built” to achieve the undertaking in which the America failed. Very likely the teaching of experience will be found to support him in the belief that the balloon must be larger, not smaller.

Kiddo the cat was renamed Trent in honour of the rescue ship and enjoyed his fifteen minutes of fame. I can’t help but wonder how Vaniman felt when he saw the headlines.

Bluffton Chronicle – June 14, 1911

** HOW CAT WON LASTING FAME

From the notoriety viewpoint “Kiddo,” the cat mascot of the airship America during the recent sensational 1,000-mile voyage over the Atlantic has eclipsed the human portion of that dauntless crew.

Gimbel Brothers, a popular American department store, had a gilded cage set up and filled it with soft cushions for the celebrity cat to recline in while on display to the public. Commemorative postcards of the event almost all included the cat.

The first successful aerial crossing of the Atlantic came nine years later (May 1919), when U.S. Navy Curtiss N-4 flying boat flew from Rockaway New York, to Plymouth, England over a 23 day period.

And just a few weeks later, the first cat successfully completed a trans-Atlantic trip (which was also the first crossing from Britain to America) on the British airship R-34. Whoopsie (or possibly Wopsie) was also a last minute addition to the ship, brought on board by William Ballantyne, the first human stowaway. Ballantyne had been employed as a rigger but then was left behind to make room for an observer. He hid himself and the cat between the girders and the gas bags but soon became airsick and revealed himself. By then the airship was over the Atlantic so he was allowed to remain as long as he earned his keep. Whoopsie became the airship’s mascot and accepted as crew, remaining with the ship for the next two years until it crashed in 1921. Whoopsie suffered a bruised paw. The ship was written off.

Walter Wellman had apparently had enough of aerial challenges and instead took to writing, publishing multiple books about his explorations and about the politics of the time.

Trent aka Kiddo the cat also retired from aviation, moving to Washington DC to live with Wellman’s daughter, Edith.

Vaniman died on the airship Akron during another attempt to cross the Atlantic in 1912. As they departed Atlantic City, there was an explosion and Akron crashed into the sea, killing all five men on board.

The navigator of the America, Murray Simon, did eventually make it across the Atlantic in an airship, when he was invited on the maiden translatlantic voyage of the Hindenburg.

The America was never seen again although sightings of it were reported as far away as South America and Ireland. Maybe it was, in fact, the first airship to cross the Atlantic.

References:

- Wikipedia

- America the airship: the first transatlantic crossing

- Kiddo, the airship cat

- “Roy, come and get this goddamn cat” was the first ever in-flight radio transmission

- How Cat Won Lasting Fame

- Animals Aloft

Great anecdote, it’s the little details that make history so much fun.

On a tangential note, I highly recommend Amundsen’s account of his expedition to the South Pole. It’s fascinating to see how carefully and efficiently he planned everything, he was a genius of exploration.

It’s also interesting (though somewhat depressing) to read Scott’s account of his expedition to the South Pole. Even by itself it seems terribly slipshod, and when you compare it to Amundsen, it seems criminally incompetent.

No planes involved, sadly, though Amundsen did later disappear on an aerial rescue mission.

Very good piece; however, what I found missing is how and when it was decided that Wellman and “America: moved their operations from Europe to the USA? When did it happen? Where in the US did Wellman prepare for their east-bound voyage of October 1910?

Thank you.