Alcock and Brown: Part 2

In part 1, I introduced Jack Alcock and Teddie Brown along with the context under which they raced to become the first to fly across the Atlantic in less than 72 hours.

Of course, they weren’t the only ones. In all, there were seventeen teams who wanted to attempt the crossing but most of them dropped out early. By March of 1919, there were only four serious contenders for the prize: four of the best British aircraft available at the time.

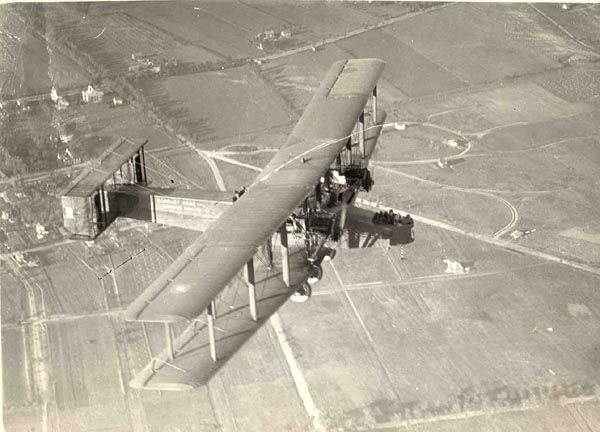

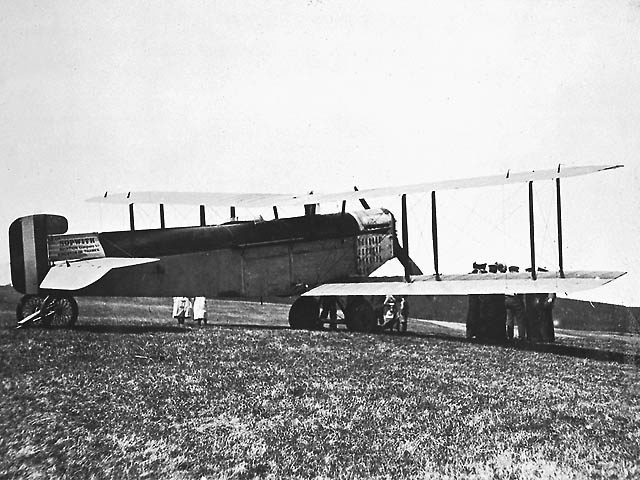

The favourite was Handley Page, with their four-engined biplane called the Handley-Page Atlantic, which was based on the V/1500 heavy bomber. The other three teams were Vickers, Sopwith and Martinsyde.

Sopwith had supplied over 18,000 aircraft to the British war effort, including the famous Sopwith Camel.

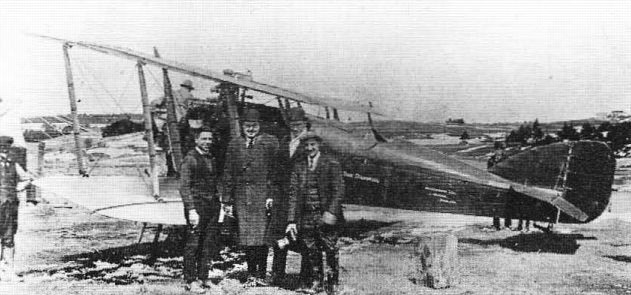

They designed the Sopwith Atlantic with the Daily Mail prize in mind, including the ability to jettison the undercarriage to reduce weight and drag. A section of the rear fuselage was also modified to double as a boat. The Sopwith team was led by Australian pilot Harry Hawker who had started with Sopwith as a mechanic but soon became their test pilot. He and his navigator Kenneth Grieve arrived in Newfoundland in March 1919. They quickly assembled their aircraft in hopes of making the crossing before the others had a chance but the weather turned and they were unable to fly.

The second team to arrive was Martinsyde, with an aircraft they called Raymor which was based on the Martinsyde Buzzard. The pilot received his pilot’s licence when he was 17 and was an instructor by the time he was 19. He worked for Martinsyde as a test pilot during the war. He and Harry Hawker had competed in many air races and become friends in the process. The two pilots struck a deal to give the other one hour’s notice when they were ready to set off.

The Handley Page aircraft was a huge aircraft and needed much longer to assemble, so although the aircraft and a crew of six arrived at Newfoundland soon after, they needed more time to prepare for the crossing.

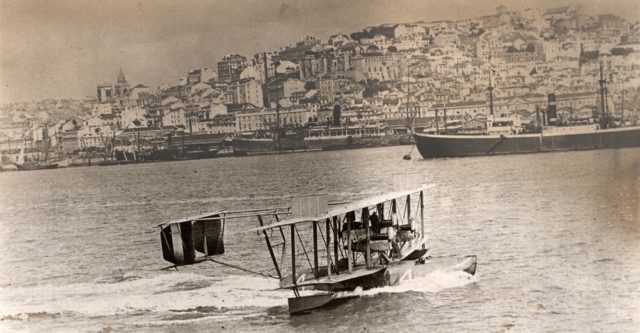

The US Navy was also attempting to be the first to fly across the Atlantic although their effort wouldn’t qualify for the Daily Mail prize.

On the 8th of May, 1919, three Curtiss flying boats, NC-1, NC-3 & NC-4, departed Rockaway Beach, New York for a five-leg trip via Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, The Azores islands, Lisbon Portugal, landing in Plymouth, England. The flying boats had been developed during the war as extended range aircraft to patrol for submarines; they needed to be able to fly from the US to the war zone in Europe, as at the time, the Germans were regularly sinking Allied cargo ships. This attempt at the first trans-atlantic flight had the benefit of manpower. Each seaplane required six crew and they were supported by three dozen Navy warships which were staggered along the route.

On the 16th of May, NC-1, NC-3 and NC-4 departed Newfoundland for the longest leg of their trip, to the Azores in the middle of the Atlantic. Navy destroyers were stationed as visual checkpoints at 50-mile (80 km) intervals along the route, shining search lights and firing shells to help the aircraft navigate to the islands.

Worried that the Navy flights would cross the Atlantic before they had even tried, Harry Hawker and Kenneth Grieve took off in the Sopwith Atlantic on the 18th of May. Alcock and Brown were still in England and the Handley Page team was not yet ready to fly.

Hawker had kept his word and warned the Martinsyde pilot that they were leaving. The Martinsyde team sprang into action, hoping that they could overtake their competition during the flight. However, the Martinsyde Buzzard, overloaded with fuel, was caught by a gust of wind during the take-off run and the undercarriage collapsed. They never made it off the ground.

Three days passed and it became clear that the Sopwith Atlantic hadn’t made it across the Atlantic. After another day without word, it seemed that they must have been lost at sea. The King of the United Kingdom sent a telegram of condolence to Hawker’s wife. But then six days after they had departed Newfoundland, the Norwegian cargo ship Mary arrived in Scotland to announce that Hawker and Grieve were safely on board.

The Sopwith biplane overheated about fourteen hours into the flight and they diverted in order to ditch in a shipping lane, hoping to hail a ship. There, they were rescued by the Mary but the ship did not have a radio, so there was no way to notify anyone that they were safe until reaching harbour. The Daily Mail gave them £5,000 as a consolation prize and Hawker named his second daughter Mary, after the Norwegian freighter.

Meanwhile, the US Navy boats were in trouble, having encountered thick fog. Suffering with the lack of visibility, NC-3 changed course upon sighting a ship on the horizon, just to discover that it wasn’t one of the “station ships” placed to help their navigation but, in fact, just a random ship transiting the Atlantic. The fog meant that the navigator couldn’t use the sextant. Lost and low on fuel, they landed on the water hoping to wait out the fog and get a fix on their location. But two of the four engines were damaged when they landed on the rough sea, meaning that NC-3 was no longer airworthy. They “taxied” across the Atlantic for 200 nautical miles (370 km) before reaching one of the islands of the Azores islands.

The crew of the NC-1 suffered similar navigational issues in the thick fog and also decided that it was safer to land. However, the ocean waves were even rougher and the NC-1 was swamped by 12-foot waves, leaving the flying boat unable to continue. They were rescued by a Greek cargo ship who attempted to tow the aircraft to land. The crew were all saved by the ship but the NC-1 was lost at sea.

The pilots of NC-4 were also disoriented by the fog, saying that it was so thick that they couldn’t see from one end of the plane to the other. They could not see the Navy ships but maintained radio contact and eventually spotted land, one of the westernmost islands of the Azores. They landed in the island’s harbour just before the thick fog obscured the island.

NC-4 departed the Azores safely for Lisbon but suffered mechanical problems after only two hours of flight and had to land in the eastern Azores. The repairs took a week. NC-4 was finally able to depart again on the morning 27th of May. Dusk was falling when the crew spotted the Cabo da Roca lighthouse on the Portuguese coast. They reached Lisbon harbour after a ten hour flight, making NC-4 the first aircraft to cross the Atlantic Ocean (or any other ocean for that matter). The flight from Newfoundland to Lisbon had taken ten days and 22 hours, with a total flight time of 26 hours and 46 minutes.

The final leg of the flight was delayed as the seaplane needed further engine repairs but NC-4 reached Plymouth, England twenty four days after its initial departure from New York. There, it was dissembled and shipped back across the Atlantic to the US.

The NC-4 holds the position as the first aircraft to fly across the Atlantic but it took them most of a month, at a time when an ocean liner could make the crossing in five days. The crossing did not inspire as much confidence in the future of aviation as they might have hoped.

The Daily Mail contest was still up for grabs.

Meanwhile, Alcock and Brown had only just arrived in Newfoundland with their Vickers Vimy. They found that the best departure fields had already been taken by the other teams and struggled to find a place to assemble the aircraft.

The modified Handley Page bomber was still not ready; the leader of the team wanted to be sure that the aircraft would be safe for the crossing.

The Martinsyde team were able to repair their aircraft but the navigator had been injured in the initial crash and they were still waiting for the replacement navigator to arrive.

Although Alcock and Brown were the last to arrive, they were the next to make the attempt, taking off in the Vickers Vimy from Newfoundland on the 14th of June 1919.

We’ll look at their flight next week in the last part of the series but I wanted to jump ahead, first, to finish the story of the Handley Page Atlantic.

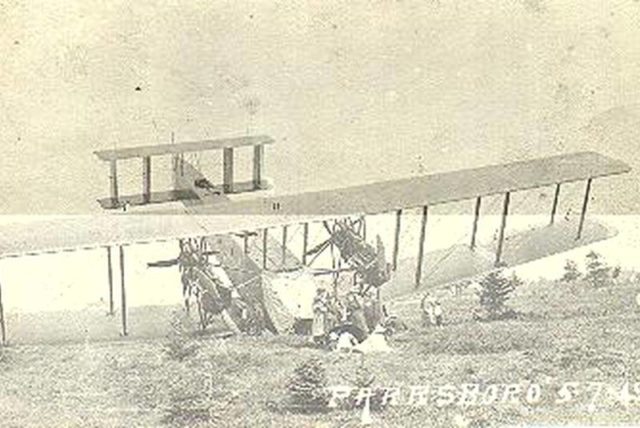

The modified bomber finally took off on the 4th of July but they flew to the United States instead of across the Atlantic. Unfortunately, they developed an oil leak during the flight and had to divert to Nova Scotia, where the aircraft landed badly. An image of this “landing” was commemorated in a post card.

The repairs took all summer but they finally arrived in New York City in October and gained the distinction of being the first first airmail delivery from Canada to the United States.

However, this small victory was not enough and the Royal Air Force replaced the Handley Page V/1500 bombers with the Vickers Vimy.

The Royal Air Force Museum Cosford holds three propellers, four sections of tailplane and a compass, all that remains of sixty-two V/1500 bombers produced for the British Air Board.

Superb research, Sylvia. And it goes to show how in the early days chance, not to say “fate” was a major factor in the progress of aviation.

“Three days passed and it became clear that the Handley Page Atlantic hadn’t made it across the Atlantic. After another day without word, it seemed that they must have been lost at sea. The King of the United Kingdom sent a telegram of condolence to Hawker’s wife. But then six days after they had departed Newfoundland, the Norwegian cargo ship Mary arrived in Scotland to announce that Hawker and Grieve were safely on board.”

That should be *Sopwith* in the first sentence, shouldn’t it?

Oh my goodness, yes! Thank you!

<*dies of embarrassment*>

Handley Page Atlantic “ finally arrived in New York City in October and gained the distinction of being the first first airmail delivery from Canada to the United States”

Wasn’t that Bill Boeing March 1919?

https://www.wired.com/2009/03/march-3-1919-u-s-starts-international-airmail-service/