Alcock and Brown: part 1

I’m going to Ireland! It will be my first time there. While I’m there, I’ll get the chance to see Dublin and Belfast and Rudy! I’m not sure which of the three is most exciting.

You can bet I’m looking forward to this, even if it means you’ll be without me for a few weeks.

During my trip, I will be part of a panel discussion about the first non-stop flight across the Atlantic and it seemed like a good opportunity to write about the background here. Wired magazine claims that “only the most die-hard aviation geeks would know” who flew the first non-stop flight across the Atlantic, which I find hard to believe. But well, I guess I count as a die-hard aviation geek, so how could I tell?

Anyway, for the avoidance of doubt, let me state clearly that the first non-stop crossing was Jack Alcock and Teddie Brown in a Vickers Vimy in 1919. My event is in celebration of the 100th anniversary of the event.

John William Alcock, known all his life as Jack, was born in 1892 in Manchester, England. His exposure to aviation came early; when he left school, he trained as an apprentice at Empress Motor Works, who built aeroplanes and rotary engines. He worked for Norman Crossland, the motor engineer who founded the Manchester Aero Club. Alcock then got a job as a mechanic for a French demonstration pilot and started taking flying lessons at the same time.

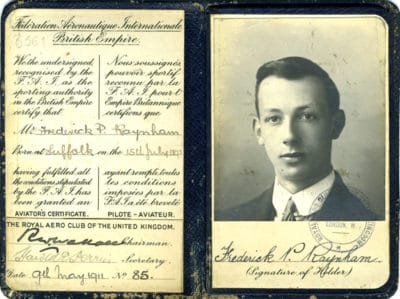

When Alcock was twenty, he was awarded an aviator’s certificate by the Royal Aero Club, the national co-ordinating body for air sport in the UK. This meant that Alcock completed the test flights which were assessed by a Royal Aero Club official. The test flights consisted of two distance flights at least 5km (3 miles, 185 yards) each in a closed circuit and one altitude flight with a minimum height of 50 metres (164 feet) which could form part of the two distance flights. At the time, there was no real requirement of getting even to modern circuit heights.

The course for the distance flights should be marked out by two posts no more than 500 metres (547 yards) apart. After each turn round one of the posts, the pilot must change the direction of flight when going round the second post so the circuit is an uninterrupted series of figures of eight

The method of alighting (landing) for each of the flights should be with the motor stopped at, or before, touching the ground. The aeroplane must come to rest within a distance of 50 metres (164ft) from a point previously indicated by the candidate

Over the next few years Alcock became a racing pilot. He went on to work as a test pilot for Sunbeam aero-engines but, when World War I broke out, he became an instructor for the Royal Naval Air Service.

In 1917, his Handley Page bi-plane bomber suffered an engine failure and he ended up having to ditch in the sea, swimming with his crew to shore where they were taken prisoner by Turkish forces. He was released in 1919 and retired from the Royal Navy, becoming a test pilot for Vickers Limited in Surrey.

The company had started as a steel foundry in 1828 but quickly expanded into steel rolling, railway industry and casting church bells. They bought out a shipbuilding company in 1897, diversified into car manufacturing in 1901, and purchased a controlling interest in a torpedo manufacturer in 1911. That same year, they formed Vickers Ltd (Aviation Department) and began developing and producing aircraft. Between 1911 and 1970, they produced over 16,000 aircraft under the Vickers name.

The Vickers Vimy was a twin-engined bi-plane developed as a long-range heavy bomber at the end of WWI to replace the Handley Page bomber.

Four prototypes were designed but the production of the aircraft didn’t really come to speed until after the end of the war. Although the Vimy had been designed to be able to reach Berlin from France carrying a payload of bombs, only three aircraft had been produced by the time Armistice was declared; the Vimy never saw active service in the war. Instead, the initial production was used as maritime patrol aircraft and home-based heavy bomber force for the RAF and development began for the the Vimy Commercial, a civilian version.

Arthur Whitten Brown, known as Teddie, was born in Glasgow in 1892 to American parents. His family later moved to Manchester and, like Alcock, he took a job as an apprentice in an engineering firm, British Westinghouse. At the start of World War I he took British citizenship in order to enlist in the University and Public Schools Brigade, one of the “Pals” battalions which were formed of men who enlisted together in local recruitment drives with the promise that they could serve together. He was later seconded to the 2nd Squadron Royal Flying Corps as an observer. He was shot down twice, the first time while on artillery observation duties and the second on a reconnaissance flight. The second time, Brown and the pilot were taken as prisoners of war by the Germans.

After the war, Brown continued to work on his aerial navigation skills. But he wanted to get married and he began to look for work that would give him enough security to do so. One of the firms he approached was Vickers, who had taken over British Westinghouse, his previous employer, in 1919.

Now it had been six years since the Daily Mail newspaper had offered a prize of £10,000 for the first non-stop flight across the Atlantic Ocean but it had never been claimed. Truthfully, it probably wasn’t possible to fly the route in 1913.

After the war, British manufacturing companies such as Vickers had shifted their military production to developing and manufacturing civilian / commercial aircraft and were looking for opportunities to promote civil aviation. A competition for the Daily Mail prize seemed like just the thing.

Flightglobal hosts the archives of Flight Magazine from 1909 to 2005, including the announcement on the 21st of November 1918, ten days after the armistice came into force, that the the Daily Mail prize for an Atlantic crossing, via the air, was now open again for competition.

The Proprietors of the Daily Mail have offered the sum of £10,000 to be awarded to the aviator who shall first cross the Atlantic in an aeroplane in flight from any point in the United States, Canada or Newfoundland to any point in Great Britain or Ireland, in 72 consecutive hours. The flight may be made either way across the Atlantic.

The entrance fee was £100 which went to the Royal Aero Club for hosting the competition. The fee was due at least 14 days before the first attempt along with the starting location and “as nearly as possible” the proposed landing place. The Royal Aero Club would then send an official to mark the aircraft and supervise the start. The mark was to ensure that it was the same aircraft that reached the other side.

The shortest crossing that would qualify was between Newfoundland and Ireland: 2,007 miles or 3,230 kilometres.

You can get a good feeling for how impossible the whole endeavour seemed from the rules. The pilot(s) could depart and land either on land or water; if departing from water, then the aircraft needed to cross the coast-line before continuing on, and the start time would be taken from that point. Any intermediate stoppages were only to be made on water. If the pilot left the aircraft and boarded a ship, he had to resume his flight from the same point.

There’s a few versions of how the Vickers Vimy entered the running. Some sources say that Jack Alcock convinced the Vickers company management that they needed to enter an aircraft into the competition. Others claim that Vickers had already decided to enter the competition and were looking for a pilot, which Alcock was happy to step up for.

Certainly, by the time Teddy Brown showed up at Vickers looking for work, the company had started modifying the Vickers Vimy for the attempt, converting the bomb racks to fuel tanks. Brown’s aerial navigation skills were just what was needed and Alcock was happy to take Brown on as the navigator for the flight.

Of course, they weren’t the only entrants. Seventeen teams had expressed an interest in attempting the crossing and now the race was on. The serious British contenders began shipping their aircraft parts in crates, ready for reassembly on the shores of Newfoundland.

Now you’ll have to bear with me, I need to get packed. We’ll continue next week!

Edit: Oh, Walter reminded me in the comments about the attempts to cross in dirigibles! So in the meantime, you may enjoy reading this post: Goddamned Cat

Interesting that the first ever transatlantic flight (but not nonstop) was made just two weeks previous, by a squadron of NC-4 flying boats. I was surprised to find that the first lighter than air crossing was not made til two weeks after Alcock and Brown. I had thought commercial Zeppelins would have already done so.

That’s exactly what I want to look at next week. :D

Interesting point not often recognised, Alcock & Brown’s first non stop flight was a major achievement and made in a twin engined aircraft. This at a time when no such aircraft was able to maintain height on one engine. Therefore two engines carried double the risk of disaster due to component failure.