Factual Version of the Clipper Eclipse crash featured in the Oatmeal

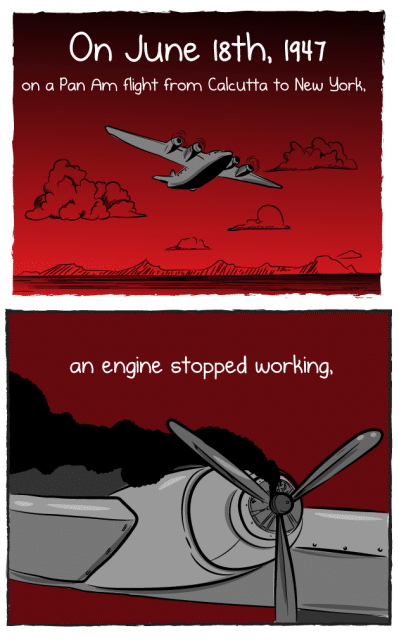

This week The Oatmeal presented a comic strip entitled It’s going to be okay about Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek, who survived a plane crash in 1947. It’s a motivational comic meant, the author says, to remind us that our journeys are short.

You can read the comic here: http://theoatmeal.com/comics/plane.

It’s a lovely strip and I don’t want to take away from the (many) people who have gained comfort from the story. But as an aviationist, I’m bothered by the fact that the sequence of events, presented as fact, seemed unbelievable or at least rather clearly embellished. I’m even more bothered that the mainstream media are now referring to the “entirely true story” which… well, the crash clearly happened but the details didn’t check out. So in the interests of keeping the facts straight, I looked up the details.

Unfortunately, the original accident report is not available online, so I read up on the crash at Aviation Safety Network and aviation history website Check-Six.

The actually true story of the plane crash is very interesting, although we lose the dominant narrator of a single brave co-pilot defying the odds to comfort a young woman and rescue the passengers. I won’t recreate the full strip here so to follow along, you should visit The Oatmeal first.

This was Flight 121, part of the brand new round-the-world service which Pan American Airways had just launched. The aircraft was the Clipper Eclipse: a Lockheed Constellation, a propeller-driven aircraft with four 18-cylinder engines.

There were ten crew on board: Captain, First Officer, Second Officer and Navigator, Third Officer, First Engineer, Second Engineer, First Radio Officer, Second Radio Officer, Purser and one Cabin Crew Member.

On the Pan Am Clippers, the third officer served as a relief pilot and was able to fill in and provide a rest period for the primary crews. Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek, was on the crew of this flight as third officer.

They departed Karachi, India at 15:37 for the flight to Istanbul, Turkey, with an estimated arrival time of 2:08 the next morning. The Connie was cruising at 18,500 feet when the number one engine developed trouble. The Captain feathered the engine, which rotates the blades to be parallel to the airflow. This has the effect of reducing drag and, on a multi-engine aircraft, helps the aircraft to maintain altitude with the reduced power from the remaining engines.

The closest airfield was Habbaniya RAF Station in Iraq. The Captain did not believe they would have adequate repair facilities and stated that they would proceed to Istanbul on three engines. Habbaniya Tower reported that all airfields on route had already closed for the night and recommended an emergency landing. The flight crew responded that they would turn back if there was any further trouble and continued to Istanbul. They separately sent a message to Karachi, requesting that Damascus Radio be alerted and open the airport. Damascus Airport readied itself to be available in case of emergency within the hour.

The aircraft continued but twenty minutes later, the remaining three engines overheated, which forced the flight crew to reduce power. The aircraft could not maintain altitude at the reduced power level and began a gentle descent.

While descending through 10,000 feet, engine number 2 caught fire. The Captain immediately initiated a rapid descent.

The number two engine had a faulty thrust bearing which blocked the oil in the propeller motor. The Captain reported the fire to to Habbaniya immediately and illuminated the Fasten Seat Belt – No Smoking sign.

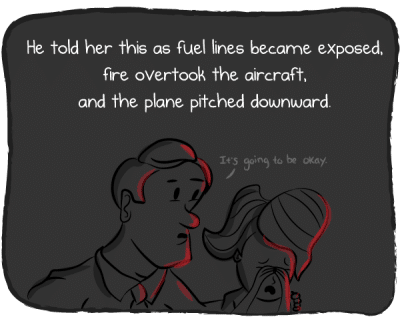

Here, the comic strip is referring to Gene Roddenberry, although it does not make that clear until the end. The implication here is that he was the first officer and left his seat to comfort a passenger because they were going down. I’m pretty sure every pilot who saw this thought, wait, what?

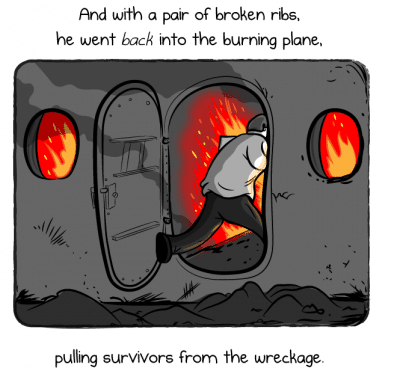

The fact is that Roddenberry was the third officer, the relief pilot on this flight. He did not leave his post but actually had no function as a part of the flight crew at that moment.

The cabin crew member saw Roddenberry in the cabin. She said she woke up to see the purser and the third officer standing in the aisle. They told her to get her belt fastened tight and then checked the passengers to make sure they were all belted in.

Roddenberry (and the purser) were briefing the cabin crew for an emergency landing; a perfectly logical action. There’s no seat for the third officer for the back, so he would have had to sit next to someone who was sitting alone. It may well have been a woman but the implication that he left the cockpit to console her is clearly melodramatic.

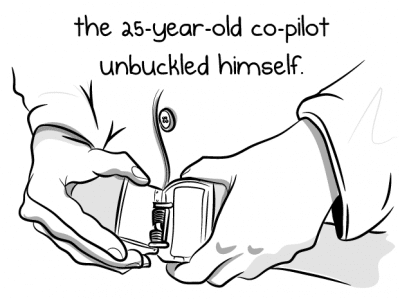

The aircraft had been “pitched downward” for a few minutes, in a rapid descent from the moment the engine caught fire. They were descending for an emergency landing. The engine fire spread to the wing and then the engine separated from the wing. The left wing continued to burn as the Captain brought the aircraft down for a belly landing in the Syrian desert.

The cabin crew member described the scene. “We hit hard on the belly with an awful jar which would not stop. We slid across the sand. The plane swung hard around to the left and split in two, pretty well forward. Flames poured in and the heat became terrific.”

The comic refers to two crew members surviving but there were three: the third officer, the purser and the cabin crew member, all of whom attempted to clear the passengers from the burning wreckage.

The cabin crew member again:

“We who could jumped out. The other survivors were handed down and we dragged them away and tried to do what we could for them. We had to carry the Rani away. She had a head injury and had lost some teeth and was in a rather bad way, but we finally quieted her.”

So again, the strip isn’t wrong but it implies strongly that he single-handedly rescued the survivors.

I’m not sure the trek across the desert ever happened; a different version of the story, also attributed to Roddenberry, says he stayed with the wreckage and sent two men to investigate lights he’d seen shortly before the crash and they brought back a radio. There’s also an unattributed version in which a small aircraft flew to the scene.

What’s clear: Eight passengers and seven crew members were killed in the crash. Roddenberry phoned in a report of the crash from Deir-Ez-Zor and emergency rescue operations started immediately.

Aviation history website Check-Six’s description of the crash includes this in closing.

Roddenberry, after the experience, left Pan Am and aviation in 1948, to pursue a career in Hollywood. He was known to embellish his story of survival, claiming that he single-handedly rescued the survivors from the wreckage, fought raiding Arab tribesmen, and walked across the desert to the nearest phone to call for help.

It’s quite clear that the comic strip is based on some version of Roddenberry’s embellishments, although there are odd factual inaccuracies (the number of surviving crew, a radio in a village) that I can’t trace.

The Civil Aeronautics Board determined the probable cause as the fire which resulted from an attempt to feather the No. 2 propeller after the failure of the No. 2 engine thrust bearing.

Aloha Sylvia,

Thank you for fact checking! I would comment that the Oatmeal’s characterization of Pan Am Flight 121 was “inspired by true events.” What the cartoon attempts to provide us is a glimmer of hope.

I’m still an optimist despite the recent crash of Metrojet Flight 9268 and the senseless murders last Friday in Paris. The perpetrators of this hate filled campaign against us is demonicly inspired. I want to believe that we can collectively turn that glimmer into a ray. And that together, that ray of hope will blind and stop those that wish to harm us dead in their tracks.

I like “inspired by true events,” that’s absolutely true. And that’s not to say there’s something wrong with it; just that it was so bizarre to think of the “co-pilot” leaving the cockpit to console some poor woman in the cabin as they are preparing for an emergency landing!

Quick clarifying question. In 1994, competing biographies of Roddenberry were published. Joel Engel’s book insists that Roddenberry was seated in the passenger cabin for the duration of the flight. David Alexander’s book (authorized by Roddenberry’s estate) insists that Roddenberry was seated on the “flight deck” (Cockpit? Forgive me, I’m not an expert on this kind of jargon.) and was ordered to leave and help the passengers in the main cabin. My question is: was there even a seat for the third officer to take in the cockpit of this aircraft? Or did he, as Engel claims, just have a seat amongst the passengers?

Bearing in mind I am working off secondary sources, but Roddenberry’s being in the cabin at all is corroborated by the stewardess who awoke to find Roddenberry and the purser standing in the aisle. One could take that to mean that he wasn’t in the cabin previously but it’s not really clear from that. I found one reference that said he was a deadheading pilot (i.e. off duty using the flight for transport) which would put him in the cabin but the accident report categorically names him as third officer.

There’s more crew than I think there could possibly be seats on that flight, but I don’t know aircraft. I’ll see if I can find out.

Multiple newspaper stories at the time list Roddenberry as the third officer on the flight, so claims that he was “deadheading” can be dismissed as erroneous. Unfortunately, Roddenberry hasn’t been quoted in any of the stories I’ve found, although the other two crew members to survive – the flight’s stewardess and purser – do get to tell their version.

I her you regarding secondary versus primary sources, though. To that end, I’ve emailed both the librarians at the University of Miami (where the Pan Am collections, including papers related to this accident, are kept) and author Joel Engel (who says in his Roddenberry biography that his account is based on primary sources), to see if they have anything.

Oh wow, that’s brilliant, Michael. I would love to hear if you come up with anything!

I haven’t heard anything back from either source, sadly (though I will try the University of Miami librarians again once the Thanksgiving break is over; my initial email may have fallen through the cracks due to the impending holiday).

Subsequent to those inquiries, I have found the Civil Aeronautics Board’s Accident Investigation Report, which is available here: http://specialcollection.dotlibrary.dot.gov/Document?db=DOT-AIRPLANEACCIDENTS&query=%28select+381%29

What would really help fill in the blanks would be any minutes from the public hearing this report says was held on August 5-7, 1947 in New York, NY. Some quotes from this hearing can be found in a New York Times article published on August 6, 1947. The article quotes Jane Bray, the stewardess who survived the crash, as saying, “I looked out of the window at the stars and waited and waited and waited, either for the burning engines to drop off or for the ship to blow up. I knew we had been flying at 18,500 feet and I didn’t see how we could get down from that altitude with the whole wing on fire. But I didn’t say a word. Nobody did. There was no crying, no panic. Nobody even turned their head, that I could see. I guess we all just waited.”

Her comments surely paint a different picture than the comic, which states that the burning engine “caused a panic.”

The same article goes on to say, “In questions to [Anthony] Volpe [the surviving purser] emphasis was placed on the fact that the flames he saw were bright, white ones-‘like a rocket taking off,’ he said. It was suggested that such a blaze, uncontrollable by ordinary means, could only have come from magnesium in the parts and fittings of the engines.”

Some dramatic license must be granted to the illustrator, of course, but the comic colors the fire as red and yellow — not bright white (I know — picky, picky).

Any luck, by the way, in determining the seating arrangement of the aircraft — specifically, how many crew members could be seated in the cockpit at one time?

It’s definitely configured for five to be seated. With the third officer in the back, I ended up with two unaccounted for. I’ve been referred to the Historical Aircraft Restoration Society in Australia, who apparently have one! So I’m hoping to hear back soon.

Thanks for referencing Check-Six on this! I always enjoy researching and writing about the facts behind aviation’s history…

Thanks for offering such a great resource for American aviation history. It’s genuinely appreciated!

Hello. I don’t know if any one of you will check back to this website in 2017, but I have been to the University of Miami (in 2010) to collect copies of the original documented investigation and crash site photos. I have some answers. I am Dave McLean, the grandson of Captain Joe Hart, who piloted this plane to its final resting place. By the way, this was a topic of discussion among my family when I was a kid.

Hi Dave,

i am certaibly interested in hearing more! I’ve collecetd a number of newspaper clippings about the crash, but haven’t been able to view any documents from the original investigation.

Dave, if you want to mail me directly on sylvia@fearoflanding.com then I’m happy to put you and Michael in touch with each other via email. I’d also love to see what you’ve found and hear your story, of course.

Hello. I don’t know if any one of you will check back to this website in 2017, but I have been to the University of Miami (in 2010) to collect copies of the original documented investigation and crash site photos. I have some answers. I am Dave McLean, the grandson of Captain Joe Hart, who piloted this plane to its final resting place. By the way, this was a topic of discussion among my family when I was a kid.

Hi Dave,

My Grandfather’s name is Charles Shohan and was a survivor on this flight. At the time he worked for the State Department and resided in Alexandria, Va. My Father (Charles son) is still alive and can recount the memories my grandfather had of the crash. I can be emailed at jenniferboo@mac.com

Dear Dave:

I am interested in anything you learned about Pan Am Flight 121, which I understand your grandfather piloted on its fateful journey in 1947. My stepmother’s first husband, was William Edward “Eddie” Morris, who was one of the flight engineers and was killed in the crash. I agree with many of your comments and would love to speak with you.

Hi Arlene … I am interested in whatever you would like yo speak about.

You may reach me via email below.

Thank you got your interest!

Well, thank you for your interest! I believe Sylvia will put us in touch. Best regards, Dave M.

Hi Jennifer, and thank you for writing. I have sent you an email note to the account you come above. Best, regards, Dave M.

Hi,

My grandfather was also a survivor of this crash. He was a young doctor back then accompanying his friend to turkey for a surgery.

I recently, just a few days ago, found out that my grandfather had written a small book about this crash. I just acquired the book few days ago and am just starting to read it. Hopefully it will provide some more details about this unfortunate event.

My Grandfather”s name: Dr Ghulam Nabi Bajwa.

I would be fascinated to hear what you find out from that book.

Dear Raza:

My stepmother’s first husband, William Edward “Eddie” was one of the flight engineers on Pan Am 121 that crashed in 1947. He was killed in the crash. I saw your post about your grandfather and the book Dr. Ghulam Nabi Bajwa wrote about the crash. I would love to speak with you.

Amazing that no one faults the pilot for pressing on with a crippled aircraft. He should have landed at the first available airfield. If he had done that, there would have been no crash and all would have survived.

I have often wondered about that (Theodore S. comment). Captain Hart was a seasoned pilot. My interpretation was that he made a judgement call based on the health of the remaining three engines that could allow a safe completion of the flight to Istanbul, albeit at a lower altitude than flying with all four engines. And as it turned out, Engine No. 2 had been mechanically problematic prior to this fateful flight, and knowing that, I am surprised that once that same engine exhibited mechanical problems during Flight 121, the decision was made to press on. Hart was to make another decision at 1:00 AM GMT about the health of the engine and the plane, but the infamous fire broke out well prior to this decision point. Once Engine No. 2 dropped from the wing and a fire spread to the fuselage, it seems the plane’s fate was sealed. I would have to check my notes of the flight transcripts to see what oral communications were sent back and forth from the flight deck (cockpit and radio desk and navigation desk behind the pilots’ seats, forward of the galley) to nearby airports, notably Habbinaya in Iraq. The interested reader can find these hour by hour and minute by minute recorded communications in Accession I: Box 120b Folder 119 and Accession II Box 103 Folder 10 at the Richter Library at the University of Miami. Photographs of the crash and the debris field, plus a hand drawn map, are also present. The oral histories of third officer Roddenberry, stewardess Bray and purser Volpe are available as well in a separate folder.

pressure on pilots from airlines was strong in those days(often at the cost of safety) his stated reason during the flight for not landing at the RAF base was lack of repair facilities. This could have resulted in the plane being stuck there indefinitely (this had happened in the past) I financial disaster for the airline. It would have been up to the captain. His view would have been that the plane could fly on two engines and he had (at that time) only lost one which was feathered so no big problem, he also assumed he could return to the RAF base if any other problem occurred (he stated this by radio). He got it wrong, he wouldn’t have expected a second engine problem but he should have allowed for the possibility.

This was a lovely-looking airplane that changed air travel but it was not a safe one, piston-driven aircraft rarely were, it was not the only one to have an engine detach in fact. 99 were built and there were, in all, 26 hull losses, over a quarter loss rate!!!

Just fascinating stuff.

Thank you for the clarity, Paul C! That is useful and interesting information. I did not know just how dangerous these early Constellation aircraft were, being susceptible to engine failure. Just FYI, one of the engines that failed onboard Flight 121 had experienced mechanical issues on the plane’s earlier flight across the Atlantic from Gander to the British Isles and had to turn back to Gander for part replacement. And Captain Hart had noticed fluid leaking from that engine while walking around the aircraft on the tarmac at Karachi (not Calcutta as The Oatmeal suggests), according to David Alexander’s biographical account of Roddenberry. During the final flight of this particular Connie, Captain Hart has also considered landing his aircraft in Damascus, as you may know. That option was taken away from him immediately after it had been discussed with his bridge crew members (including radio transmission) when the fire broke out. All in all, it is remarkable that approximately half of the people on board the aircraft actually survived this crash, which includes their ordeal on the desert floor once they were “safely” away from the wreckage.

Oops. I believe that my earlier comment about fluid leakage was noticed by the captain while in Rome, rather than in Karachi.

I have read all the comments. My grandfather was one of the unfortunate people to die that day. We have some records and a letter from Jane Bray. He was on his way back to England from India.

I would love to know what happened to his body and where he is buried ?

Hi Colin … the remains of the PanAm staff were buried at the site of the crash in Syria. The internment of several bodies (probably ashes) is recorded for posterity in a silent PanAm film of a few seconds in duration, captured several days later during the CAB investigation of the crash site. A letter written to the family of radioman Miles by a local chaplin in Deir Et Zor suggested a memorial service was held there on behalf of those who died.

Thanks Dave

My sister has most of the information. So i will see if she has anymore she can share

For your information. My grandfather was called Desmond Vernon.

Thank you, Colin. I would be interested. Hope to hear from you again soon.

Hi, My name is ArleneWaters, and my stepmother’s 1st husband, William Edward “Eddie” Morris, was the flight engineer and was killed when the plane crashed. I have researched the flight and I am willing to mutually information. I have attempted to put together a list of passengers, which I would love to compare with others. Colin, who was your grandfather? I would love to hear from both of you.

Hi

My father Syed Muhammad Raza and his elder brother Syed Muhammad Haider survived the crash of PAN AM flight 121. My father received burns on his back and his brother on his hands. They were treated at the Beirut hospital. My father received skin graft treatment for his burns.

I am interested in the manifest of the passengers. I have my father’s passport on which they travelled back. The original passport was

destroyed in the fire. They were issued a new passport in Beirut Lebanon on 9th September 1947 for travelling back.

Hello Colin. I have copies of the flight crew and passenger manifests, and your grandfather is listed on it, age 43. His occupation was listed as “merchant”. He was not the only RAF member on board that flight. Also present was Michael Graham, age 25, an RAF pilot during the war. He is quoted as saying that he “survived ten air mishaps in the war” (NY Times, 23 June, 1947).

Arlene

His name was Desmond Vernon. He had a business in Chennai ( Madras) before the War. He was then in the RAF during the war!!!

I believe that the entire flight crew served in military during the war. I am on a time crunch workwise but want to explore further with you. If I don’t get back to you in two weeks, please contact me at arlenewaters120@gmail.com. Arlene

Hello Arlene. To my knowledge, all, or at least most, of the officers served in one capacity or another during the war. I can’t recall if Purser Volpe or Stewardess Bray served. My grandfather, Captain Hart, was seconded to the US Navy as an aviator while continuing to fly for Pan American Airways throughout the conflict.

Your stepmother’s first husband, Mr. Morris, is listed as “Asst. Engineer Officer”. My condolences to you and your stepmother.

Kind regards, Dave M.

i like comics and all that stuff, but somehow they can never draw a plane right.

for example the donald duck pocketbooks: a plane with just 6 windows, tough it has the nose section of a 747, FOUR engines and the tail of a cirrus vision jet (v tail). dear mister walt disney, please learn your comic writers some basic aviation rules and some airborne physics please, greetings: an irritated aviationgeek.