Aviation Airspeed Guide

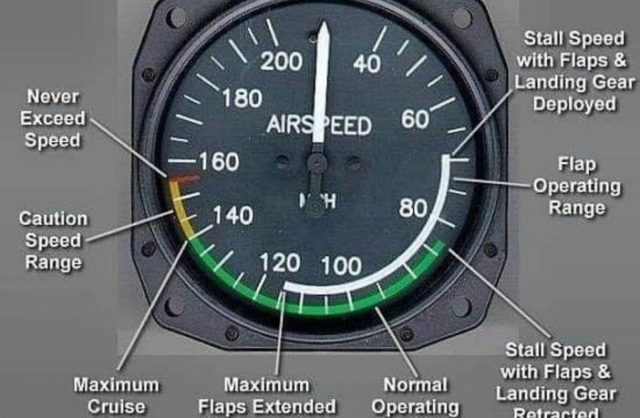

Just a quick one today but I really liked this guide to the airspeed indicator which was published to r/aviation.

The thread has ended up in an interesting discussion about Vne (the never-exceed speed) and why the gauge goes up to 200 on an aircraft which can’t (or shouldn’t) exceed 155 knots. The comments range from the helpful to outright silly.

The airplane is not structurally rated for 155+, the aerodynamic stresses are dangerously high for that aircraft at that speed.

Are you legally obligated, once you reach high yellow zone, to announce, “She can’t take much more, captain!”?

The diagram in the link below breaks the limitations of an aircraft down into a diagram that gives a better visualization of the green and yellow arcs on an airspeed indicator and the red Vne line. It takes a bit to compare an airspeed indicator to the diagram, but this was been one of the best learning tools that I have seen to compare structural limits to the airspeed indicator.

http://learntoflyblog.com/2016/01/04/aerodynamics-vg-diagram/

Some pilots prefer to use the whole speed indicator. The wings aren’t nearly as courageous however, and decide to watch the whole thing from a short distance behind the plane.

I read this in David Attenborough’s voice. I could listen to this for hours.

Oh god, it would be amazing and tragic at the same time.

And here we have the majestic cessna, taken its final landing as it plunged itself into the banks of the river Thames. Small vessels like this one are prone to being taken by the turbulent winds of England. One minute it was soaring freely and the next it is surrounded by the bustle of a pack of crash investigators. Bystanders look on in horror as the wreckage is pulled apart piece by piece, revealing the mangled and malformed structure that once carried life through the skies. This is all a part of the cycle, of the living, breathing, planet earth.

On jets and large turboprops there are no painted regions or other markings. This is mostly due to the massive variation in what the limit speeds can be based on combinations of weight, altitude, air temp/pressure, etc.

Every airliner I’ve flown has what’s called a barber pole for the max speed (it’s red and white striped needle, like what you’d see outside a barber shop). The barber pole shows the never-exceed speed for the current conditions. So it will move depending on atmospheric conditions and altitude, and changes from a max indicated speed to max Mach speed at a certain altitude.

There is no caution range in jets/turboprops either. Not sure why, you’d have to ask an aeronautical engineer. Stall speed will vary so much on big planes that it’s not permanently marked on the airspeed indicator either. On the 767, max takeoff weight can be 440,000lbs, and lowest with just 2pilots and minimal fuel is 220,000lbs. Minimum speed with flaps up in those examples can be as high as 265kts, or low as 195kts.

Old school gauges have bugs we move to show minimum speeds for each flap setting, and digital gauges show the flap bugs along with a low-speed awareness queue. That can look different based on whose avionics are in the plane. The E-170 has a white/amber/red line in the speed tape showing how close to or into the stall you are, but on the 757 it’s just a little amber bracket above the bottom barber pole.

Flap speeds aren’t posted on the gauge either, not in any permanent way. However, it is something we have to know. I fly 4 variants of the 757/767, and each variant has different flap limit speeds. Our airplanes also have both an old-school airspeed gauge and an electronic speed tape, and on the speed tape the max speed for the current flap setting is shown by the barber pole moving down to that speed. For example, Flaps 20 on the 757-200 is 195kts. Once I’ve selected that, the barber pole on the speed tape moves down to 195 from where it was previously. The barber pole on the OG airspeed indicator does not, however.

Hope that helps a little

I had just gotten out of the Air Force when a friend asked me to deliver a Citabria for him. I’d never flown a tail dragger so he arranged for an instructor to take a few trips around the flag pole with me to show me the technique.

The instructor was about eighteen and somewhat humorless. He decided to give me a little quiz right after takeoff, and so I heard over the interphone from the back seat, “OK, can you tell me the stall speed of this aircraft?”

(Now, you have to understand the one-g stall speed is pretty meaningless to the military…they emphasize that the aircraft stalls at any speed when you exceed the stall angle of attack. I had completely forgotten about the white arc on GA airspeed indicators.)

It seemed like a strange request at 300 feet on takeoff leg, but I said, “Sure”.

I pulled off some power, pulled the nose up until the airspeed bled off, then recovered from the resulting stall. “It’s about 50”, I replied. “Want to see it spin?”

He didn’t ask me any more questions.

A bit of light-hearted fun but also it was intriguing, to me, to see the amount of general interest in how planes work.

I do have one question, though, which is why the hell is the airspeed indicator in mph and not knots?

Yes, why is the airspeed indicator marked in MPH and not in KTS?

A good question for which someone may be able to come up with an answer.

The first twin aircraft I was properly rated on was a Cessna 310Q. In the USA most twins, even a King Air, are covered by a generic twin rating. In some countries a rating is required for commercial operations. In the Netherlands any aircraft with a maximum take-off weight over 2000 kg required a rating. This applies to the class of e.g. the Twin Comanche, Seneca, Partenavia, etc.

These aircraft do not perform well on one engine. The joke going around at the time was that the second engine, in the event of an engine failure, would carry you to the scene of the accident.

Actually the Partenavia performed well on one engine.

But I digress.

The speed indicator in the 310Q was in MPH.

I flew other 310s. Some, like the later “R” with the long nose, had the speeds indicated in KTS. I cannot seem to remember that it was a problem. The cruising speed, for my navigational calculations was 180 kts TAS. Easy: divide distance in nautical miles by 3 = time (still air). We used to cruise at 9000 – 11000 feet so the IAS was not all that relevant anyway.

I cannot remember what indications were displayed in the Piper Aztec, Navajo, Cessna 340, 402 etc. I suppose they were in kts.

The Citations, King Air, the Learjet, Corvette as well as airliners I flew: small ones like the ATR 42, the Fokker F27, Fairchild FH227, Metroliner, Fokker 50, Shorts Skyvan and 360 as well as the BAC 1-11, they all had the indications in kts.

It seems that many light aircraft intended for use by private owners have the speed indicated in MPH. Why? I don’t know.

The speed indicator, the instrument itself can be used in different types of aircraft. All that differs is the scale, the dial face. Only the areas with the markings: caution, red line, etc., may differ. It saves money. Many cars have the same: The indicator of a car with a top speed of, let’s say 160 kph, may go to 240. Maybe a version with a larger, more powerful engine can hit that higher speed. In the meantime it saves money and it gives the owner of the car with the smaller engine that warm feeling that the speedo suggests that he can go a lot faster.

Not a good idea in an aircraft with a structural speed limit ! But then, a pilot is supposed to have a certain sense of responsibility, and heed the limitations as indicated by the markings on the instruments.

It’s amazing how much information can be conveyed on a simple airspeed indicator. Obviously, this is on the simple end of the scale, but I’ve come to realize that simple aircraft can be a wonderful experience and certainly a fine training tool.

The units used on the ASI can vary from aircraft to aircraft; I think it’s specified somewhere in the aircrafts type’s certification paperwork. My old (UK) gliding club’s tugs were Supercubs (US) marked in MPH and Robins (French) marked in knots. This was quite convenient as the climb speeds you’d tend to pick for different conditions worked out about the same, numerically, across the types, i.e., you’d usually tow a bit quicker in the Robins by about the ratio of the lengths of nautical miles to statue miles.

Wait till you guys hear that Russia and, presumably, some other places, use kilometers/hour on their airspeed indicators!

Not only that, but it turns out km/h is actually the ICAO-recommended unit for airspeed, although they (graciously) permit the usage of knots as an alternative temporarily, and no termination date has been set for the switchover to kph.

https://www.pilot18.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Pilot18.com-ICAO-Annex-5-Units-of-Measurement.pdf

I deliberately did not mention Eastern Europe.

In the ‘seventies we flew to places like Belgrade, Ljubjana, Sofia, Bucharest, Budapest, Warsaw etc. Still firmly behind the “Iron curtain” then.

In many of those countries we were confronted with the metric systems.

Often I had to keep a conversion table handy:

“Climb to flight level 4000 metres” – what was that in feet exactly?

It is highly unlikely that km. per hour will replace the kts. It has been too deeply embedded by now.

For comparison, here is a long article on the speeds that must be considered by jet pilots in the various phases of flight: https://safetyfirst.airbus.com/app/themes/mh_newsdesk/pdf/safety_first_special_edition_-_control_your_speed.pdf

It describes a lot more speeds than those indicated on the GA dial. For example, I learned that there’s a “maximum brake energy speed”, above which the brakes catch fire if you decelerate to a stop, and a speed above which the tires burst. The plane usually lifts off between these two. Then there’s “green dot” speed, below which drag increases, which makes your speed unstable: above GD, you can set a thrust and the pplane will keep its speed even if momentary variations occur, but below GD, if there’s a decrease or increase of speed (e.g. due to wind), the speed will continue to decrease or increase unless thrust is adjusted!