The Stolen Boeing

It shouldn’t be so easy to lose an aircraft.

Especially a big old airliner. It was 47 metres (153 feet) long and 10 metres (34 feet) high, with a wingspan of 33 metres (108 feet). Twice the height of a giraffe and four times the length of a London bus.

The aircraft was a Boeing 727, registration N844AA, and it has not been seen in 13 years, despite a worldwide search by US security forces.

It wasn’t a particularly exciting aircraft, in fact it was barely airworthy. Maury Joseph, the president of Aerospace Sales and Leasing, Inc, was the effective owner. In 2001, he owned three 727s which had been retired by American Airlines, all three in almost mint condition.

Maury Joseph sold N844AA to a South African entrepreneur, Irwin, for a million US dollars, who wanted it, and a crew, to fulfill a contract to supply fuel to diamond mines in Angola.

Joseph says he was paid $125,000 as a down payment. He removed the passenger seats from the cabin so that it could be installed with ten large fuel tanks. He agreed the aircraft could be taken to Angola but insisted that one of his employees travel with it, so that he could make sure the money came through. On the 28th of February in 2002, still carrying the American Airlines livery, the aircraft departed Miami for Luanda.

It’s unclear what the details of the deal were but certainly, only two payments were ever made. Maury Joseph never got his money.

One of the original crew posted on the Professional Pilot’s Rumour Network (PPRuNe) about their arrival.

When 844AA first arrived in Luanda from the USA it was grounded by the local Fed’s because it didn’t have an HF radio. An HF radio taken from a Cessna 206 (or close to it) including the long coaxial antenna was installed on 844AA.

It may be possible to identify the aircraft by inspecting the belly and identifying the holes drilled aft of the EEC door along the center line of the belly where the antenna from the 206 was installed. The first hole would be roughly 3/8 diameter directly aft and close to the EEC access door and then approximately 8 more 1/8″ holes drilled approx. 4′ apart running aft along the belly. Attached to these holes were brackets that the antenna was attached to. So it is possible that on inspection from an experienced 727 mechanic or flight crew member and if these holes were not filled in,they may be able to identify these non conforming holes in the belly thus confirming that the aircraft is 844AA. By the way, after this bizarre installation of the HF antenna designed for a Cessna was installed on 844AA, the local Fed’s signed it off.

After it was approved by the authorities in Luanda, it was removed because we were well aware of the fact it was non-conforming, illegal and so on. It was the biggest laugh we had the whole time we were there. We had another option and that was to install an HF that was purchased by Mr Irwin and we found out after the fact that it was from a Angolan military aircraft. It was quickly returned as far as I know.

The director of Angola’s civil aviation authority told the Associated Press that the aircraft had been grounded for about a year because it lacked the proper documentation verifying its legal conversion to a tanker. He also said in a radio interview that the aircraft was banned from overflying Angolan territory on account of a series of irregularities.

Certainly, the deal flying the fuel for the diamond mine didn’t work out and another cargo deal seemed to only consist of 17 flights before the crew left. Soon, Maury Joseph’s employee (who was meant to ensure Aerospace Sales and Leasing, Inc got their money) was the only one of the original crew left. Joseph fired him in the spring 2002, as the money was never forthcoming and the employee kept making excuses not to bring the aircraft back.

The aircraft stayed at Luanda, effectively abandoned.

Joseph eventually found a buyer for the engines, which had only had around a thousand cycles and were now the only part of the aircraft with value.

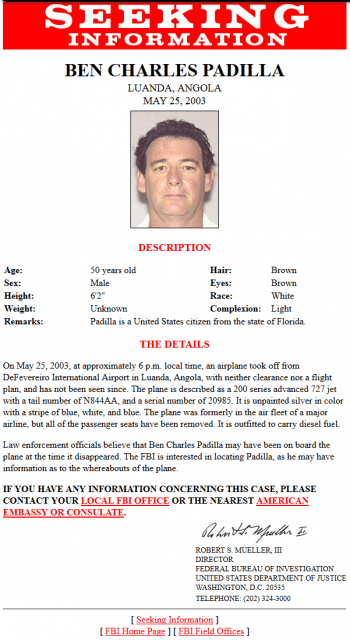

Ben Padilla was a freelance flight engineer who lived in South Florida with his fiancée and two children. He had worked for Maury Joseph before and was happy to take on the job to fly to Angola in April 2003 to pay the outstanding fines and hire local mechanics in order to get the aircraft airworthy. He presumed, correctly, that the South African entrepreneur hadn’t paid any of the bills.

Padilla hired Air Gemini to work with him to restore the 727 to service in Luanda. Within a month, the aircraft was airworthy again.

Padilla hired a pilot and co-pilot from Air Gemini in order to deliver the aircraft to Johannesburg. Padilla had a private pilot’s licence but no commercial licence and was not rated for airliners or jets.

The plan was that Maury Joseph would meet him there with the new customer for the aircraft. Padilla arranged with Air Gemini that, the day before the flight, he would take the aircraft from the hangar to the main runway, so that he could run all three engines up to full power for a systems check.

On the 25th of May, shortly before sunset, Padilla and his hired assistant, John Mikel Mutantu, boarded the aircraft. They ran up the three engines and then, without contacting the Air Traffic Control tower or any clearance, the aircraft began to taxi. The lights were off and the transponder was not transmitting as it “manoeuvred erratically” and entered the runway.

The aircraft went to full power and rumbled down the runway.

Mutantu, who had accompanied Padilla to help him with the aircraft, was not a pilot. Padilla was, but he was only a PPL, he had no experience with large jets. The Boeing 727 was set up for a three-man flight crew.

With lights off and no communication, it took off from the runway, turned southwest, and flew out towards the Atlantic Ocean.

No one ever saw it again.

The following morning, Joseph was waiting in Johannesburg for the delivery of the 727 when Air Gemini phoned him, demanding to know why another crew had flown the aircraft out of Luanda. Joseph must have been very confused about what had happened, but soon after the phone call, he contacted the US Embassy in South Africa to report the stolen plane. He also called his wife, still in Florida, and asked her to inform the FBI.

In the aftermath of 9/11, US intelligence were extremely interested in the 727 and immediately began an international search. President Bush was given daily briefings on the case.

It was no use. Padilla, Mutantu and the 727 had disappeared without a trace.

Padilla’s family believe that there was someone on the aircraft waiting in ambush for Padilla and his helper, and that they were killed or held hostage.

Some thought it was arranged to be stolen by Maury Joseph in order to collect the insurance money. But Joseph says no insurance money was ever paid: in order to file a claim he had to prove that the aircraft had been stolen and with no trace of the aircraft, he had no proof.

In 2005, the FBI closed its case, no closer to solving the mystery.

Journalist Tim Wright has spent a lot of time investigating the mystery and his articles in Air & Space Magazine are well worth reading:

The 727 that Vanished

When Airliners Vanish

The aircraft might have been kept hidden or scrapped, but no trace was ever found. The aircraft was never seen again and none of its parts were ever spotted, although there were many who were looking.

It seems more likely that the aircraft crashed into the Atlantic Ocean shortly after take-off and by the time the search was on in earnest, three days later, all traces had been washed away or had sunk.

This is one more than likely of the cases that never will be solved. Already enough time has passed to allow debris to have corroded, exposed to seawater, to a point where identification will be impossible. Assuming that it did crash into the sea, the most likely explanation.

During the times when I flew in Africa, at many airports there were abandoned aircraft. Abandoned because of conflicts, mercenary missions, unsafe and closed-down operators, maintenance issues that had not been resolved, sometimes because it had been operated by crews who had obtained their licence – it they had one – from a local forger, unpaid bills, you name it.

Vegetation does grow very rapidly in the tropics. The last time I was in Nigeria, near the old runway at Lagos there were several aircraft, from jet airliners to abandoned military aircraft. that had been left parked for such a long time that the “bush”, the vegetation, had nearly entirely swallowed some of them.

I once was asked by a Danish owner to return an aircraft from Kaduna on their behalf because the lease had not been paid. It was a small turboprop. I cannot remember the type but it might have been a King Air or a Cheyenne. When I inspected the aircraft it turned out that it had been flown extensively by some unknown and incompetent pilots, needless to say without the owners’ permission and without any proper maintenance. The engines had been “cooked” and it had to be abandoned.

I also once took a job flying a Lear Jet 25, based in Lagos. The private owners used it to fly in Africa but also from time to time to the UK. We had to make use of apartments, some actually very luxurious, that had not been cleaned in months, perhaps not in over a year and various people had used them. Bedlinen had never been replaced. Disgusting. But the worst was that we carried a list of airports that we had to avoid because the bailiffs would impound the aircraft if we did land there. Once, we had filed a flight plan from a German airport back to Lagos via Tamanrasset. We were already out on the taxiway when a police car with blue lights flashing drove out in front of us and blocked our way. The bailiffs were just in time. The owners paid the bill and two days later we departed. That aircraft was eventually taken and sold by order of a court, but I had in the meantime found another employer, another Lagos-based Lear 25D (5N-ASQ). The owner of that aircraft actually treated us well, behaved like a true gentleman and paid his bills.

The gist of my reaction is that there have been very many dubious operators all over Africa, and many aircraft have disappeared. Some of them kept operating without proper papers and without C of A, perhaps flying arms or involved in some other illegal operation until they crashed somewhere, either over the jungle or in the sea, or lack of maintenance eventually caught up.

I once have flown over the jungle trying to locate the wreckage of a crashed B727 (no, not the one in the article). It was not very far from Lagos, the location was known. It had been flying arms, was burnt-out and the crew had not survived. I could not find the wreck, even though ATC directed me to the spot.

I remember a couple of years ago the folks over at airliners.net were joking about finding it, repainting it in the site’s colors and using it as a private jet for airliners.net members only! LOL!

Also, wouldn’t drilling holes into a pressurized airliner be a bad idea, unless you knew where to drill and were able to reinforce the holes somehow.

Is it at all possible those holes could have caused or contributed to an explosive decompression? Or are they too small and too far apart to cause that sort of damage?

I believe the aircraft was checked for airworthiness but certainly, it made it from Miami to Luanda without any mishap, so the holes themselves would not have been a problem.

Ah what a nice idea! But an old 727 may well be more expensive to operate than calling net.jets for a Gulfstream. On the other hand, the fuel tanks that still may be on board could be converted to an on-board, in-flight swimming pool. Sell it to Donald Trump and perhaps in a year it will be “Air Trump One”!

On a more serious note: A few little holes are hardly going to make a difference to the pressurisation, a few rivets would solve it. But you are right: if drilled in the wrong places and by mechanics who perhaps did not know what they were doing, they may over time develop into something more dangerous. Like the fatigue cracks that doomed the Comet 1. The B727 was “built like a brick sh..house” and anyway probably not going to be around much longer, even if it had not been what looks like been stolen. So it does not look like it would have been a problem. But Africa is not a kind place for ageing airliners.

According to one pilot, the fuel tanks were actually all water tanks anyway, so you might be more right than you expected when it comes to Air Trump One!

One thing we have to admit: Trump does know how to “play” an audience.

But that won’t solve the riddle of the lost 727.

In the end, the most likely scenario is that it crashed in the sea.

And even if that can be proven, the riddle still is a long way from being solved.

Dick Drost flew it back to Roselawn Indiana

Salt war corrodes aircraft aluminum very slowly: many WW2 aircraft on remain underwater in good condition after 60 years or more. Commercial airliners have serial numbers everywhere. If the wreckage is ever found, it will be easy to identify. The problem here is 1) where to look; and 2) who would want to pay the millions it would cost for an underwater search, particularly in view that the aircraft may not even be in the Atlantic. Nonetheless, N844AA may be found by chance some day.