Night Flight from Catalina: Beechcraft Baron Incident

On the 8th of October 2024, a Piper Arrow departed from Santa Monica Airport in Southern California, landing at Catalina Airport, the small airport in the centre of Santa Catalina Island.

Catalina Island is a small rocky island with rough terrain about 25 miles off of the coast of Los Angeles. The islands there are the remnants of an ancient mountain range; on Catalina, the highest peak is Mount Orizaba with an elevation of 2,097 feet (640 metres). I grew up in Los Angeles and my school played Avalon at sports, and I have fond memories of the entire varsity team throwing up over the side of the hour-long ferry for the entire trip there and home. Needless to say, we lost.

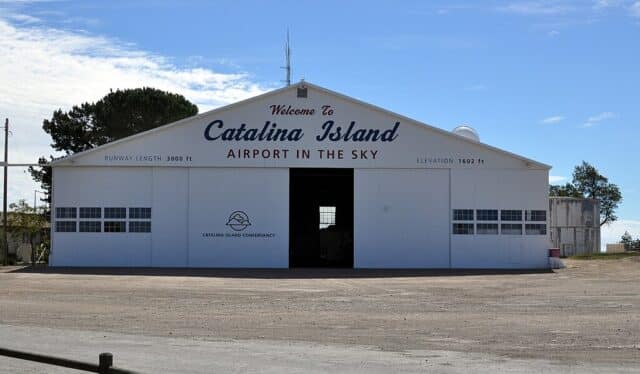

Catalina Airport is open to general aviation from 08:00 to 17:00. The airport does not offer night operations and there is no lighting. It is sometimes rather romantically referred to as “Catalina Airport in the Sky”, a reference to the airport perched at the centre of the island at an elevation of 1,602 feet (488 metres), surrounded by steep cliffs. A pilot who goes by Coyote Stan commented: “Everyone should get an opportunity to land and take off from this runway. On a good day clear skies it’s an adventure.”

The runway (04/22) is a tabletop runway with no overrun protection. Runway 22, the standard runway in use, heads southwest, with the California coastline. The first 1,800 feet of runway 22 has an uphill incline of around 2% before levelling out with a slight downward slope. The last 700 feet of the runway aren’t visible until you approach the crest. Aircraft departing runway 22 have a take-off run towards a ravine, with no lights or landmarks ahead, only cargo ships and the horizon of the Pacific Ocean. If you carried on straight, the next city lights would be in 6,800 nautical miles as you approach Tasmania.

That day, the Piper Arrow was carrying two flight instructors and a student pilot from Proteus Aero, a flight school based in Santa Monica. However, during their pre-flight check on Catalina, they discovered a mechanical issue. They would not be able to fly back to the mainland.

Pilot Ali Safai was a retired flight instructor who had owned a flight school at Santa Monica Airport until 2018. He still had an aircraft based at the airport, a twin-engine Beechcraft 95-B55 Baron registered in the US as N73WA.

Safai had friends at Proteus Aero and heard about the instructors and student who were stranded on the island. He offered to fly across and pick them up.

Although the airport closes at 17:00 and there are no night operations, flights are often granted permission to arrive and depart after hours, as long as it is still light out.

According to a local pilot on Reddit, the ops office at Catalina has a big whiteboard listing aircraft that didn’t pay their landing fees or took off without permission. “They are not welcome back.”

The airport’s general manager told local press that they’d agreed that Safai could land after closing, with an ETA of 18:20. However, the general manager is adamant that no one had approved the aircraft to depart after sunset.

The Beechcraft Baron arrived at the airfield safely shortly after 6pm, presumably with Safai and another student pilot on board.

San Clemente Island is the southernmost island in the same island range, about 45 miles from Catalina. Weather reports from the Naval Auxiliary Landing Field on the island warned of a low cloud ceiling, overcast at 700-800 feet.

On the 8th of October, the sun sets at 18:27 and it is completely dark from 19:49, the end of astronomical twilight. However, it wasn’t until 8pm that the five people travelling on the six-seater Baron, described as three flight instructors and two student pilots, were ready to go.

The wind favoured runway 22, as usual, but at only 5-7 knots, it wasn’t really a factor.

They would have been accustomed to using runway 22 and, having decided to take off after dark with overcast weather, they may not have considered that it would have been safer to depart on the uphill slope directly facing the mainland coastline.

Two days after the crash, Juan Brown posted an analysis of the incident on YouTube. Not all of the information had been released yet, so some details vary. What struck me, though, was this quote in the comments, from Kerry McCauley’s Ferry Pilot: Nine Lives Over the North Atlantic. This description both strikes me as incredibly relevant to this crash and also led me to pick up a copy of McCauley’s book for myself.

I lined up on the runway as straight as I could using the only two runway centerline markers I could make out over the nose of the Seneca. There might have been a momentary hesitation in my hands before they shoved the throttles forward but soon I was speeding down the runway. It was a lot harder than I thought it would be. I could barely make out the edge of the runway and the centerline stripes came at me faster and faster. My feet danced on the rudder pedals as I fought to keep the plane going straight down the runway.

If things started to get away from me I’d have to jam on the brakes quickly to avoid running off the side of the runway. But I had it. The centerline stripes were coming at me faster and faster, straight and true. As my speed increased I lifted the nose of the plane slightly prior to takeoff, but when I did that the nose blocked the few centerline stripes that were my only visual cues to keep going straight. I was speeding down the runway with my main wheels still firmly planted on the asphalt blind as a bat. Crap. I hadn’t thought of that. I was going too fast to stop so I locked onto the directional gyro compass and used that to hold my heading.

An odd sense of calm came over me as I roared blindly down the runway. It was as if I just accepted the situation as unchangeable and could only do what I could do. Instead of trying to haul the plane off the ground early I let the speed build up normally and smoothly rotated into the air.

I didn’t feel the plane hit any runway lights so I assumed I’d managed to keep the plane going straight enough for government work. When I saw the altimeter start to climb I raised the landing gear and let out the breath I’d apparently been holding. Dinner was excellent.”

This struck me as likely the closest that we might know of the feeling of the take-off run that night.

However, just as the altimeter started to climb, the Baron faltered. According to ADSB data, they were just 75 feet above ground when the aircraft entered a rapid descent of 1,700 feet per minute as they passed the departure end of the runway.

At 20:08, the Avalon station of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department received an SOS emergency notification from a mobile phone. “The cellular device stated the user’s cellphone has been involved in a collision with possible injuries and provided a location as GPS coordinates,” the Sheriff’s Department posted in a statement.

Deputies raced to the airport, as did the Los Angeles County Fire Department, the Avalon City Fire Department and Avalon Search and Rescue. They saw the tail of the air craft, about a mile west of the airport and 300 feet below. There were no survivors.

The LA Times spoke to the airport’s general manager.

On Tuesday, Safai had permission to land at 6:20 p.m. on the condition that he and his passengers leave before sunset, True said. “They did not comply.”

It’s not clear why the group stuck around for more than an hour and a half, long past sunset. But at least as big a mystery, in True’s mind, is why they decided to take off heading west over the darkest side of the island and the black ocean. That’s the standard direction in the daytime, so it might simply have been habit.

The Proteus Instagram account posted a sad and shocked statement.

Nothing can make sense of the horrific events that transpired, and we may never have all the answers to the questions we are asking. Life will never be the same for any of us.

The LA County Medical Examiner has listed the cause of death of all of the occupants as blunt force trauma in the ravine.

It is not known who was piloting the aircraft. That said, even if the pilot of the Baron had suffered a heart attack or some other form of incapacitation, it should not have been fatal. With a flight full of student pilots and flight instructors, the person in the right seat should have been at least capable of pitching up in those first few seconds.

More likely is that the pilot, and perhaps the other passengers, suffered from a common somatogravic illusion that occurs when flying into the dark without a visual horizon.

As humans, we rely heavily on visual information, with 80% of our spatial awareness coming from what we see. Without that data, other sensory data is easily misconstrued. One result of this is the “pitch-up illusion”, where the acceleration of the aircraft is incorrectly perceived as the aircraft pitching up.

During takeoff, you may have felt the sensation of being pushed back into your seat as the aircraft accelerates. The otolith organs in your inner ear track changes in orientation with respect to gravity using calcium carbonate “stones” which are pushed back just as you are. However, they also shift back the same way when you tilt your head back to look up. Normally, you can look out the window and confirm that you are accelerating on the ground. However, without visual references, your brain misunderstands what is going on: it treats the sustained acceleration as the head tilting back. As you know that you are looking straight ahead, the only sensible conclusion is that you (or specifically, the aircraft that you are in) must be pitching up.

As the aircraft lifts off, the sustained acceleration and pitch-up force creates the sensation of climbing away steeply at a critical moment of flight. This powerful false sensation, if not interrupted by visual data, can lead pilots to quickly correct the perceived excessive pitch by pushing the nose down to what feels like a safer climb away from the runway. In fact, the aircraft is now descending.

This illusion is particularly dangerous as it most commonly occurs when taking off at night, when there is very little room for error. If this is what happened on the Baron, the other passengers on board may easily have suffered the same illusion. Especially in a single-pilot operation, it’s possible that even with five pilots on board, no one realised the aircraft was descending instead of climbing.

As we await the NTSB’s report, questions remain about the decision to take off that night and the sequence of events that followed. Presuming no taxis and no easy accommodation, what would you have done?

With special thanks to Gail Snyder for permission to use the excellent photograph of the aircraft.

“Go fever” has killed many an airplane and a Space Shuttle.

I would assume since the pilot is a retired flight instructor with a twin, that he’d be instrument rated. Personally, if it’s as pitch black without lights with no horizon as described, I’d be on instruments even before the wheels came up.

Is there any sign that, unlike Kerry McCauley, he “haul[ed] the plane off the ground early” and eventually stalled?

And no, I’d be sleeping in the hangar if necessary. No horizon, no fly.

Actually that should read “Personally, if it’s as pitch black without lights with no horizon as described, I’d be in the hangar having a drink.”

The circumstances somewhat remind me of “The Mysterious Disappearance at Mull”. That, too, was a night take-off, with the pilot having a short time before he took off.

https://fearoflanding.com/accidents/the-mysterious-disappearance-at-mull/

I hope NTSB takes a hard look at herd mentality / groupthink as it relates to aeronautical decision making. Of 3 CFIS aboard, 0 refused to fly. 3 thought it was OK to risk not only their own lives, but the lives of two students.