TransAsia Flight 222 CFIT and criminal charges against ATC

There’s some odd news today which had me scurrying for the original accident report in order to make sense of a court case against two Air Traffic Controllers in Taiwan.

TransAsia flight 222 crashed near Magong Airport on the Penghu archipelago on the 23rd of July in 2014.

The Aviation Safety Council (ASC) released their final accident report on the investigation of the flight at the end of January of this year.

It was a scheduled domestic flight which from Kaohsiung International Aiport to Magong Airport. The aircraft was an ATR-GIE Avions de Transport Régional ATR72-212A (ATR72. There were 54 passengers on board, along with two flight crew and two cabin crew. Typhoon “Matmo” was a tropical cyclone which brought typhoon force winds and torrential rainfall to the area. The storm reached its peak intensity the day before, with maximum sustained winds of 155 km/hr (84 knots, 100 mph) with gusts of 212 km/h (115 knots, 132mph). It was on a northwesterly track, emerging over the Taiwan Straight early on the morning of the 23rd.

That afternoon, Typhoon “Matmo” was about 142 nautical miles (263 km, 164 miles) from Magong Airport, delaying the departure of the flight. The typhoon warning for Magong Airport was terminated at 17:40 (local time). Kaohsiung Ground Control warned the flight crew that although the typhoon warning had ended, the weather conditions at Magong Airport were below landing minima. The flight crew decided to continue the flight and hold until the weather improved.

TransAsia flight 222 departed Kaohsiung International Airport at 17:45.

The Magong Airport meteorological report (METAR) released at 18:00 showed winds at 17 knots gusting to 27 knots with visibility 800 metres in heavy thunderstorms with rain. The clouds were scattered at 200 feet, broken at 600 feet with cumulonimbus (thunder clouds) at 1,200 feet and overcast at 1,600 feet.

Mahgong Airport has a single runway, runway 02/20. Runway 02 has an instrument landing system (ILS) and the landing visibility limitation is 800 metres.

The runway in use that evening was runway 20 which included a VOR non-precision approach system and required a landing visibility of 1,600 metres.

The aircraft entered a holding pattern at 18:11. During the flight, the captain commented that he was very tired and yawning can be heard on the cockpit voice recording.

At 18:27, the Magong Tower Controller informed the flight crew that the visibility was 800 metres. The wind was 200° at 12 knots gusting 16 knots: straight down the runway.

The flight crew discussed the possibility of landing on runway 02 with a tailwind. At 18:29, they requested radar vectors for the runway 02 instrument approach.

Magong Airport is a civil/military joint-use airport. A change in the active runway can only be authorised by the Magong Air Force Base duty officer. Three inbound aircraft requested runway 02 and the ILS approach as runway 20 was no longer suitable in the low visibility. The application was still under consideration when the 18:40 weather report showed that the visibility had improved to 1,600 metres.

At 18:42, while the flight crew were still waiting for clearance for the instrument approach on runway 02, Kaohsiung broadcast that the visibility for runway 20 had improved to 1,600 metres. Upon hearing this news, the flight crew requested the runway 20 VOR approach instead (as did the other two flight crew who had requested 02).

The air traffic controller issued headings (radar vectors) and a lower altitude. The Automated Weather Observation System (AWOS) runway visual range had dropped to 800 metres again but this was not broadcast to the flight crew. The tower controller was concerned that the Automated Weather Observation System visibility was different from the visibility as reported by the weather observer. The controller discussed this with the tower chief and agreed to use the visibility information as reported by the weather observer, which was 1,600 metres.

Later, the weather watch office supervisor clarified that when the Automated Weather Observation System runway visual range values were less than the observed visibility, the weather observer should use the Automated Weather Observation System visibility for the report.

But at the time, 1,600 metres visibility was left to stand. At 18:55, the aircraft was flying at 3,000 feet about 25 nautical miles northeast of the airport and the flight crew were cleared for the VOR approach for runway 20.

The captain was the Pilot Flying and the first officer was the Pilot Monitoring. They descended to 2,000 feet and continued; the minimum altitude for overflying the final approach fix was 2,000 feet. Shortly before they overflew the final approach fix, the flight crew selected the altitude of 400 feet and started their descent. They didn’t conduct an approach briefing nor did they go through the descent/approach check lists.

The cockpit voice recorder picked up the sound of the windshield wipers increasing in speed; the aircraft probably penetrated the heavy thunderstorm rain in the area.

The minimum descent altitude (MDA) for Magong runway 20 VOR approach is 330 feet. The flight crew must not descend below this altitude unless they are able to see the runway. If the visibility is so bad that the runway is not in sight by the minimum descent altitude, the approach must be broken off the flight crew can continue the approach but must not descend any further.

The 500 feet auto call-out sounded in the cockpit and the captain said, “Um, three hundred” as the aircraft passed through 450 feet. The selected altitude was set to 300 feet.

There was no discussion in the cockpit of the minimum descent altitude or whether to continue the approach.

The captain said “Two hundred,” as the aircraft descended through 344 feet. The selected altitude was set to 200 feet. The aircraft kept descending.

As it descended through 249 feet, the first officer said, “We will get to zero point two miles,” referring to the missed approach point

At 219 feet, the captain disengaged the autopilot and said, “Maintain two hundred.” The aircraft maintained an altitude between 168 and 192 feet for the next ten seconds as they searched, ignoring the minimum descent altitude. The flight crew who had landed previously said that there was a sudden heavy rainfall. The airport was in the middle of a heavy thunderstorm with the rain falling at 1.8 mm per minute. Visibility was down to 500 metres.

This is the point when the captain asked the first officer, “Have you seen the runway?” They had just passed the missed approach point. The yaw damper was disengaged without any comment, although this is a configuration change that should always be announced.

| Captain: | Have you seen the runway? |

| First Officer: | Runway… |

| Captain sighs. | Wow, hahaha. |

| First Officer: | No. |

| Captain: | No. |

| First Officer: | No, sir. |

| Captain: | Okay, okay, okay. |

As they looked for the runway, the altitude, course and attitude of the aircraft began to deviate from the settings. The aircraft heading drifted from 207° to 188° as the aircraft went into a gentle left turn away from the approach course. The pitch angle went from 0.4° nose up to 9° nose down, then returned to 5.4° nose down. The aircraft descended.

Neither of the flight crew commented on any of this until they both shouted “Go around” at the same moment. The aircraft was at 72 feet.

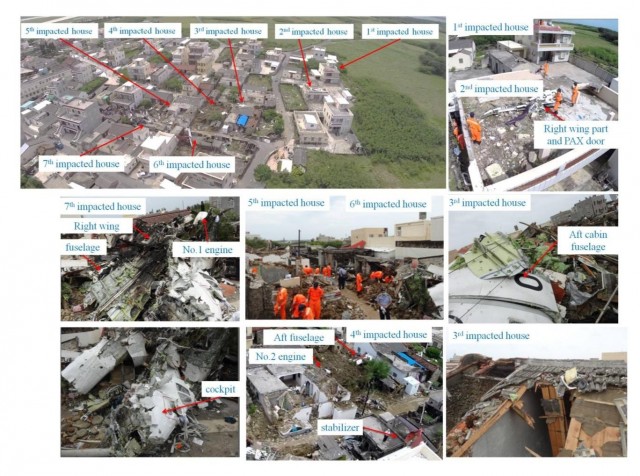

The engine power was advanced to full but it was too late. The aircraft struck foliage (trees) 850 metres northeast of the runway 20 threshold and then crashed into a residential area.

The aircraft was destroyed. All of the crew and 44 passengers lost their lives. Ten passengers and five residents on the ground were injured but not fatally so.

Investigators found that non-compliance with standard operating procedures was tolerated at the airline and that routine violations were normal. Flight crew were known to skip briefings and descend below minima while still looking for the required visual references. Even when the airline was under official observation as the result of this accident, crews tested on the simulator showed “significant non-compliance” with standard operating procedures.

Other pilots at the airline said that the captain had good flying skills and was very confident. Some mentioned that the captain had landed safely in bad weather where other pilots might have initiated a missed approach.

The first officer, as Pilot Monitoring, was responsible for the flight’s safe operation and should have alerted the captain about every deviation from the standard operating procedures, instead of supporting the actions. He was not monitoring the aircraft’s altitude and did not highlight that they had descended to the minimum descent altitude, let alone challenge the decision to continue to descend.

The coordination at the airport was also an issue. I’ll quote directly from the report for this, as it relates to today’s news.

At the time of the occurrence, the mechanisms in place for weather information and runway availability coordination between civil and military personnel at Magong’s joint-use airport were less effective than what they could have been. In particular, the inconsistent information or discrepancies regarding airport visibility during the aircraft’s approach were unresolved. In addition, the rapidly changing AWOS RVR data was not communicated by the tower controller to the occurrence flight crew. Those inconsistencies meant that there was no collaborative decision-making relationship between the civil air traffic controllers, military weather observer, and flight crew. That resulted in the occurrence flight crew not being fully aware of the rapidly deteriorating RVR while on approach and the high likelihood that the RVR would not be sufficient for landing. Had the local controller provided the flight crew with RVR updates during the approach, it may have placed the crew in a better position to determine the advisability of continuing the approach.

One thing to think about: The missed approach point for the runway 20 VOR approach was 2,000 metres from the threshold and so if the visibility was 1,600 metres, the flight crew would not have been able to see the runway from the missed approach point. As far as I can see, they could never have done that approach with anything less than 2,000 metres visibility.

The investigation concluded that the deliberate flight below the minimum descent altitude was the primary cause of the accident. You can read the findings and the recommendations on the ASC website here: Aviation Safety Council Releases Final Report on TransAsia Airways Flight GE 222

The occurrence was the result of controlled flight into terrain (CFIT), that is, an airworthy aircraft under the control of the flight crew was flown unintentionally into terrain with limited awareness by the crew of the aircraft’s proximity to terrain. The crew continued the approach below the minimum descent altitude (MDA) when they were not visual with the runway environment contrary to standard operating procedures. The investigation report identified a range of contributing and other safety factors relating to the flight crew of the aircraft, TransAsia’s flight operations and safety management processes, the communication of weather information to the flight crew, coordination issues at civil/military joint-use airport, and the regulatory oversight of TransAsia by the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA).

The full accident report in English is here: Aviation Safety Council GE222 Final Report.

Meanwhile, the reason this has come up today is because two air traffic controllers have been prosecuted in relation to this accident.

Two air traffic control officers charged for Taiwan’s worst crash in decade

“The four people are found to have been negligent in their duties over this crash,” the Penghu prosecutors said in a statement on Thursday, referring to the two air traffic control officers and the pair of pilots.

The pilots will not be prosecuted, but ground staff in charge of air traffic that day are being sued for criminal negligence, which carries a jail term of up to five years.

Prosecutors said on Thursday that a senior duty officer at Magong, Ching, along with another member of staff Li, contributed to the crash by not allowing the plane to land.

This is disturbing because although there were clearly communication issues, the air traffic controllers were not in a position of “allowing” the aircraft to land and they certainly didn’t advise the flight crew to descend too low and continue to search for the runway in the rain. In fact, if anything, the controllers could have been more negative about the situation, by reporting the lower visibility figures. The aircraft was not low on fuel nor had the flight crew declared an emergency. It’s hard to see any sense in this court case at all.

Of course, the information so far has been minimal and perhaps it will look more sensible once more details come out but right now, I’m not liking the sound of this at all.

Great article, as always, Sylvia. I’m only familiar with U.S. regulations and procedures, but there are two points that I think are worth clarifying:

The article states that “If the visibility is so bad that the runway is not in sight by the minimum descent altitude, the approach must be broken off.”

In reaching the minimum descent altitude (MDA) of a non-precision approach, such as the one being flown in this case, without the landing environment being in sight, the pilot must level off and not descend further. However, they are permitted to continue the approach until reaching the missed approach point.

“The missed approach point for the runway 20 VOR approach was 2,000 metres from the threshold and so if the visibility was 1,600 metres, the flight crew would not have been able to see the runway from the missed approach point. As far as I can see, they could never have done that approach with anything less than 2,000 metres visibility.”

I can see why it would be confusing that 1600 meters visibility is the minimum since it would seem legally impossible complete the approach in these conditions. However the pilot needn’t see the runway in order to continue below the MDA. In the US, at least, there are many other visual references that are acceptable, such as the runway lights or the approach lighting system. One assumes that in poor weather conditions the lights would be on and set to maximum brightness, enabling them to be seen beyond the reported visibility limit.

You are absolutely right about the MDA – that was bad of me. Of course they can carry on until the MAPt, just not descend further.

That’s also a good point regarding the lighting. I understood that in this case, there was no chance that the crew could see the runway lights from 2,000 feet away but I will look at that again.

Finally had a chance to look closer. Runway 20 doesn’t have a simple approach lighting system but it dos have Runway End Identification Lights (flashing white) which were brighter but, apparently, less visible.

“The MAPt for the runway 20 VOR approach was about 2,000 meters from the threshold. The visibility landing minima was 1,600 meters. There is a high likelihood that the occurrence flight crew would not have been able to visually identify the runway at the MAPt when the visibility was just above landing minima.

The installation of a simple approach lighting system with the sequence flashing lights on the outer portion would probably increase the likelihood of crews being able to visually locate the runway in degraded visibility in the future. ”

The investigation concluded that the runway 20 VOR missed approach point wasn’t in an optimal position. “With the same Obstacle Clearance Altitude, if the MAPt had been set closer to the runway threshold, it would have increased the likelihood of flight crews to visually locate the runway.”

So basically, I cut out a chunk because I wanted to stay focused on the ATC issue, but I thought they were saying that in minimum vis, the runway lights would be expected not to be visible at the missed approach point.

Judging from what has been presented here, I do not seem to find any reference to an explicit landing clearance.

Air traffic control seems to have been a bit nonchalant, especially considering the demanding weather conditions.

I have been a commercial pilot myself and I admit to having broken rulles. If that had resulted in an incident, the blame would have been mine and mine alone.

There is a moment when the crew has to consider, no DECIDE, to go around. More so if they already knowingly and deliberately have “busted the limits” and are well past the MAP and considerably below MDA.

In many cases where pilot fatigue can have been a contributing factor, the duty roster and -periods, including preceding duty- and rest times, positioning etc, the investigators go through the records with a fine comb. Am I missing something? I do not see any reference to an investigation into the possibility of crew fatigue, other than a short mentioning of the captain’s remark and “yawning” on the CVR.

Not allowed to land? Even if true, this would have been another factor )against the crew (I do not want to blacken them more than I need to, but there are strange facts emerging): a landing clearance MUST be obtained and read back on what is presumably a controlled airport.

If no landing clearance has been issued, or missed and not read back, the crew MUST either, if there still is time, ask for a (late) landing clearance or abandon the landing, NOT continue to far below minima.

If there are culprits outside the cockpit, I would point at the airline. All airlines, including small and informal operations, must enforce adherence to the SOP’s, it is not just for the big airlines. So the Operations department and the Chief Pilot share the blame.

Judging from the story as I read it here, to indict ATC seems bizarre to me.

Huh, Rudy, that’s an interesting point. I will go back over the report but I have no recollection of an explicit cleared to land.

What is my fault is that I didn’t get deeper into the question of fatigue. They did go through the preceding duty and rest times and although they state that based on the yawning, the captain was clearly moderately fatigued, there was no issue with the flight crew’s work schedule. However, they also point out that the ATR pilots at the airline admitted that they were most likely to take short cuts when they were feeling fatigued from the normal work schedule.

Regarding fatigue, the investigation concluded that the captain’s performance was probably degraded by fatigue (based on the CVR: yawning, occassional lapses on radio, and some incorrect selections that were corrected by the FO) but they don’t know why.

“However, the flight crew’s operating pattern in the three days before the occurrence commenced and ended at Kaohsiung. Therefore, the flight crew spent the three nights before the occurrence in company provided accommodation in Kaohsiung. While the flight crew had sufficient opportunity to obtain sleep, the investigation was unable to determine the quantity and quality of sleep obtained by the flight crew in Kaohsiung.”

So looking again, I found it in the interview of the local controller.

“When the interviewee issued the landing clearance, GE222 was on about a 5 or 6 nautical mile final, approaching and descending into the airport. The aircraft stopped descending at an altitude of 300 feet or so. When GE222 reached a one or two nautical mile final, the tower controllers heard their go around call. The interviewee issued the missed approach procedure to GE222, but there was no response. ”

The go-around call was within seconds of the initial impact. So although it wasn’t mentioned in the factual information when the report goes over the sequence of events, the controller stated that they were clear to land.

PS: Sufficient visual cues can indeed include (a portion of) the approach lights

Some airlines, like KLM, have adopted a “VDP” or visual descend point.

The crew will work out an approach, based on a continuous calculated descent which should result in determining the VDP.

This, no need to say, must not be below MDA. But it can be, and often is, before the MAP. The airline does NOT allow the crew to level off at MDA and “grope” for the runway.

With modern FMS (flight management systems), based on GPS, it is possible to plot a very accurate approach profile.

Of course, it is always up to the crew to decide. Major airlines are very strict when it comes to descending below the limits; the crew that does will not get a tap on the shoulder – unless it is a tap and: “Step inside my office for a moment, I want a word with you” – the word in question being a “bollicking” from the chief pilot.

I still am wondering what the meaning is of ATC “not having allowed the flight to land”. Still the same: No landing clearance = go around. If ATC failed to issue a landing clearance, that still does not constitute a refusal to allow a plane to land. And most certainly not the basis for a lengthy jail sentence.

Hello, Sylvia. Do you have any update of this prosecution of ATCO? How it ended up?

thx

Sorry, we found it, thanx

http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2017/06/02/2003671760

zuzana

Great! Thank you for sharing, I didn’t actually know the outcome.

Can we also talk about Hofstede’s power distance because of Taiwanese culture (PM didnt make a single warning, is it because he thinks he wont be listened by his superior)