“Totally a visibility issue.”

On Sunday, the 27th of November 2022, a single-engine aircraft made national US news when it crashed through power lines in Gaithersburg, Maryland, coming to rest on a lattice tower. I wrote about the incident at the time as Mooney crashes into power lines but that piece was focused on the crash and the rescue. The NSTB has now issued their final report, working through exactly what happened that day. I’ll be repeating the key points from my previous article, but first, I want to correct my comment about flying the Mooney.

Mooneys are amazing and Mooney pilots are maybe just a little bit crazy, is what I’m saying.

I want to start by apologising to all Mooney pilots for that, because their comparison to the pilot in this case was most unfair. The pilot that day was just a little bit crazy in completely his own way.

That Sunday morning, the pilot and his girlfriend departed Montgomery County Airpark in Gaithersburg, Maryland for a two-hour flight to Westchester County Airport, in White Plains, New York, where he was helping his girlfriend’s son with the purchase of a condo. A few hours later, the pilot obtained a weather briefing and filed an IFR flight plan before departing Westchester to fly back to Montgomery County.

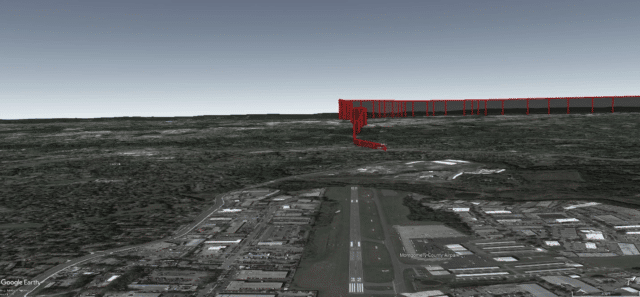

By now, it was dark and the weather in Gaithersburg had deteriorated with fog and low cloud ceilings. The pilot was instrument rated and the flight was on an instrument flight rules (IFR) flight plan: that is, they did not have to stay visual for the flight. However, the METAR for their destination showed an overcast ceiling at 200 feet above ground level and fog.

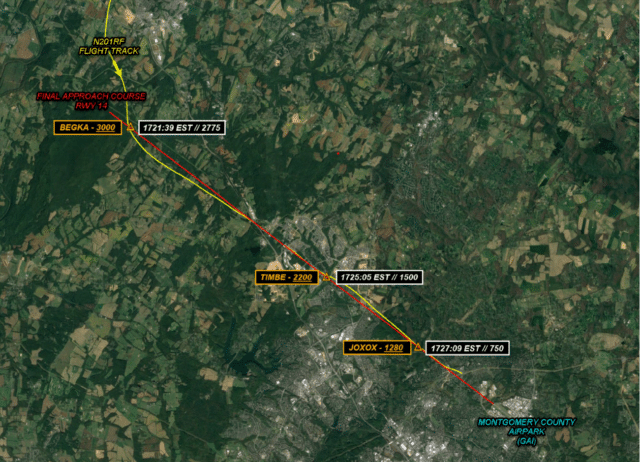

Montgomery County Airpark (GAI) is at about 540 feet above mean sea level. Runway 14, a 4,202 foot runway , was in use. During the final stages of the flight, air traffic control told the pilot to expect the RNAV A approach to Montgomery County. The pilot asked for the RNAV GPS RWY 14 approach, which had lower minimums.

There are three categories of instrument approaches for the RNAV (GPS) runway 14 approach procedure at Montgomery County:

- Localiser Performance with Vertical guidance (LPV) : decision altitude 269 feet above ground level

- Lateral Navigation/Vertical Navigation (LNAV/VNAV) : decision altitude 399 feet above ground level

- lateral navigation : minimum descent altitude of 460 feet above ground level

The decision altitude and minimum descent altitude are the altitudes at which the pilot must initiate a missed approach if the runway is not in sight. The pilot is not to descend below these altitudes until they can see the runway lights.

If the cloud base was at 200 feet above ground level, the pilot of the Mooney that day had a problem, even using the best option of the localiser performance with vertical guidance (LPV).

His troubles began before he even started the approach. Air Traffic Control cleared him to fly directly to BEGKA, a waypoint southwest of him. However, he seemed to struggle with this instruction: instead of a gentle left turn towards BEGKA, he turned sharply to the right.

The controller told the pilot that he appeared to be navigating northwest and offered a heading to BEGKA. He then gave an updated heading instruction. The pilot replied that he was descending to 3,000 feet. The controller told him to maintain 4000 feet and to proceed directly to the RUANE waypoint.

The pilot said he would turn right to fly direct to RUANE. The controller informed him that it was a left turn to RUANE and asked him to confirm that his destination was GAI (Montgomery Park).

“Affirm,” said the pilot and that he was showing heading 303° to BEGKA

The air traffic control informed him that it was a 230° heading and spelled out BEGKA for him.

The pilot confirmed he was flying directly to BEGKA.

The controller confirmed a descent to 3,000 feet, the minimum safe altitude for BEGKA. The controller then informed the pilot that he seemed to be on a heading of 175° and to turn right to heading 240°.

At the same time, another aircraft on approach to Montgomery County requested a diversion, as the visibility was below the minimums required. This other aircraft, having heard the Mooney speaking to ATC, stated that it was doubtful that the next aircraft would get in.

The pilot of the Mooney asked the controller about the other aircraft’s diversion. The controller confirmed that the aircraft in front of him had performed a missed approach due to poor visibility.

The Mooney continued its approach. The pilot set an alarm to warn him when he descended below 800 feet, the minimum for the LPV ( Localiser Performance with Vertical guidance) approach. At 1,200 feet, he caught sight of the ground. He wasn’t sure of his altitudes from that point as he was focused on maintaining visual contact. He did not recall hearing the altitude alert.

At about 1.25 miles from the runway and left of the runway centre-line, the Mooney struck high-voltage power lines. The aircraft crashed through the cables and into a transmission tower.

Another pilot asked about the approach into Montgomery County. The controller said that a Piper Cheyenne had diverted but there was a Mooney still on approach. “I’m still waiting on the cancellation,” the controller said. “It looks like they made it for now.”

The Mooney was actually dangling a hundred feet above the ground, wedged into a transmission tower.

IMAGE : Photo courtesy of the Montgomery County Fire & Rescue Service

The pilot called 911 on his mobile.

Dispatch: Montgomery County 911; what’s the address of your emergency?

Mooney pilot: I’ve flown into a tower to the northwest of Gaithersburg Airport. It’s one of the electrical towers. Believe it or not, the aircraft is pinned on the tower and I don’t know how long we are going to be able to stay here and I don’t know–

Dispatch: Wait, are you the airplane pilot?

Mooney pilot: Yeah, I’m the pilot.

Dispatch: OK, stay on the line with me.

Mooney pilot: We are in the tower. We are still in the plane. And we are in a…and now, we have a light that’s coming at us, checking to see how we are doing. (shouts) Hey, how ya doing!

The dispatcher stayed on the line with the pilot for an hour and a half, during which the pilot spoke about what happened.

Mooney pilot: Totally a visibility issue. We were looking for the airport. I descended to the minimum altitude and, uh, then, apparently, I got down a little bit lower than I should have.

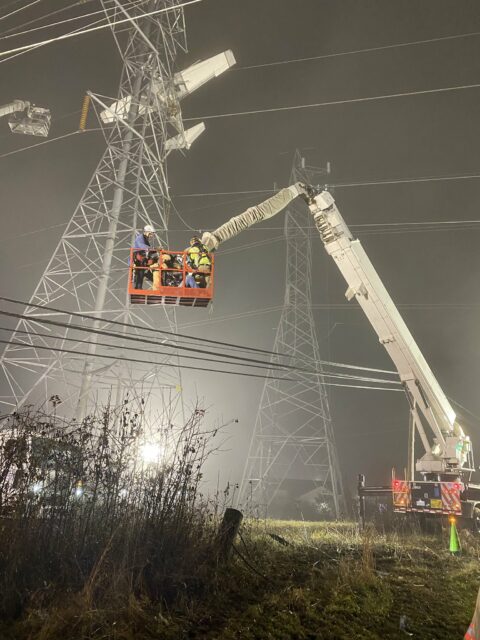

The Mooney had sheared through live high-voltage lines. The power was out for miles around. Both the pilot and the passenger were seriously injured and suffering from hypothermia.

Emergency services appeared on the scene with mobile cranes.

One firefighter said that when he arrived, the aircraft was moving and the pilot was attempting to climb out of a window. The firefighter was taken up to the aircraft after being warned that despite the outage, touching any of the power lines could be fatal.

Even the sheared through cables could contain static electricity strong enough to shock a man into unconsciousness. Engineers from the power company had to test and ground every affected power line before the first responders could even consider a rescue. They put clamps or cables onto the wires to ensure there was no risk from residual power. This took six hours.

Firefighters and the engineers finally got the all-clear at 23:30 and were able to start stabilising the aircraft.

Pilot and rescuers recount perilous plane rescue in Gaithersburg – WTOP News

No one specifically makes anchoring-a-plane-to-a-transmission-tower cable. There was no real way of testing the stability of everything that high up. Everyone had to trust their training, and there was no margin of error, the firefighters said.

They anchored the Mooney to heavy rigging in the tower and were finally able to make it to the cockpit. It was now past midnight. The pilot and the passenger had spent seven hours in the freezing cold, hoping the plane wouldn’t come crashing down.

His explanation to the dispatcher was that he descended to the minimum altitude and then apparently ended up a bit lower than he thought.

In fact, the ADS-B data showed that he’d been low throughout his approach. As the pilot flew over the BEGKA waypoint, the Mooney’s altitude was 2,877 feet, slightly over a hundred feet below the minimum safe altitude. From this point onwards, the Mooney systematically descended below every minimum altitude on the route:

- At waypoint TIMBE, the final approach fix at 5.2 miles from the runway (8.3 km) with a minimum safe altitude of 2,200 feet, the Mooney descended through 1,618 feet.

- At waypoint JOXOX, 2.3 miles from the runway, the minimum safe altitude was 1,280 feet and the Mooney was at 863 feet.

- At the point of the visual descent (visual should perhaps be in quotes here), the Mooney was still a mile and a half from the runway but flying at 587 feet.

The pilot declined to be interviewed by the NTSB and did not submit the required Pilot/Operator Accident Report Form. However, he was happy to speak to the media. When asked what led to the crash, he stated “Quite obviously I was flying too low.” He explained that the fog was like “pea soup” and that he thought his altimeter wasn’t working correctly.

The reporter asked him why he didn’t divert to another airport. He seemed to think this was something to be avoided.

“The possibility of diverting the flight to another airport always exists… it’s extremely inconvenient to everybody on the ground.”

He did admit that in hindsight, he wished he had diverted. When the reporter challenged the pilot’s decision to fly at all that night, the pilot replied, “Well, I’ve been trained to fly in bad weather”

Ten days after the accident, he agreed to speak to FAA inspectors. During this interview, he explained that although his aircraft had a panel-mounted, IFR-certified Garmin 430 GPS, he often used a handheld GPS tablet to avoid what he called the “complex keystrokes needed” to operate the aircraft’s GPS. In fact he had two handheld GPS units, both of which held data from the flight.

He said that he’d made a significant diversion from his course when he misprogrammed the Garmin 430. When asked about specific features of the Garmin, he did not appear to understand the questions.

The pilot was expecting the LPV approach, but as he turned onto the final approach course, he noticed that the LPV glideslope, which he needed to follow for the LPV approach, was not showing on his Garmin GPS.

The LPV approach relies on the pilot flying a highly accurate descent path to the decision altitude. The LPV approach offers a lower decision altitude and lower visibility minimums, allowing pilots to land in more challenging weather conditions, as they can get closer before needing to have the runway in sight.

He had no idea why the glideslope wasn’t showing on the panel-mounted unit, although given his previous statements, it seems likely he had made a mistake when setting up the Garmin 430 GPS. Neither of his handheld GPS units were certified for instrument flying; they were meant for visual flights.

He did not realise that he was already below the minimums for the LPV approach. Without vertical guidance from the glideslope, he was required to follow higher minimum altitudes for his approach. The correct response to the situation would have been to execute a missed approach, climbing to a safe altitude and either trying again or diverting.

Instead, the pilot continued as if the glideslope were there. He said he was “keeping contact with the ground through the side window” and “pulling the airport out of the soup”, showing that he was attempting to visually navigate through the clouds, a dangerous practice known as “scud running”.

He believed he could succeed where the previous aircraft had failed because he was flying a slower aircraft and “could just land long on the runway if necessary.” He was familiar with the area, he explained, and thought that he was already “inside the wires” when he struck them.

He repeatedly told the FAA interviewer that he was an excellent pilot and that he’d been complimented on his high-quality landings in the Mooney. He said that in this instance, he wanted to be an example of what not to do.

The National Transportation Safety Board was forced to rely on the media interviews and FAA interview summaries to proceed with their investigation. They determined the obvious probable cause:

The pilot’s visual flight below published altitude minimums, which resulted in collision with a powerline tower structure

The key findings were

- Personnel issues Decision making/judgment – Pilot

- Aircraft Altitude – Incorrect use/operation

- Environmental issues Tower/antenna (incl guy wires) – Decision related to condition

The NTSB could not determine whether the lack of vertical guidance on the approach was the result of the pilot’s mis-programming of the approach procedure or because he was referring to his VFR-only GPS for guidance.

The FAA suspended the pilot’s commercial pilot certificate for ninety days. He will need complete remedial training and recertification in order to reinstate it. As of writing, he has not reinstated the licence but reverted to his private pilot certificate. His medical expired in November 2024.

Once the Mooney was removed from the transmission tower, the power company was able to restore power to 120,000 affected homes and businesses within an hour.

The pilot’s post-crash concerns about his altimeter proved unfounded; testing showed that it was “well within the test allowable error at all ranges.”

You can download the NTSB’s final report and access the docket for the full details.

Excellent write up. I appreciate hearing facts without judgement. We humans are imperfect and reading about mistakes such as in this story helps us understand and hopefully avoid similar dangers. The heroes in this story were the 911 operator and first responders who rescued this couple. Note to non pilots: Be careful who you get into an airplane with

“The possibility of diverting the flight to another airport always exists… it’s extremely inconvenient to everybody on the ground.” Getthereitis much?

Yes, I get that it’s non-trivial to get back to a parked car when you’ve had to divert because the field you parked at was socked in — but that’s what you have to be prepared for; the northeast US is not a good place for light planes that are trying to keep to a planned schedule. That’s part of why I gave up flying; the one time I was PIC under instruments, traffic delays and fuel requirements meant I took much longer door-to-door than if I had driven my car.

This case also sounds like the pilot was too tired to fly competently. One of the ~reasons we don’t have flying cars is that you can’t just pull over and nap when you’re in the air — or park under a bridge when a hailstorm happens….

Sylvia, yes your attempt to be funny resulted in a bit of a “Faux pas”. But it is minor, certainly compared with the attitude of this pilot.

Yes, it is always inconvenient ending up at a different place than the (airport or) intended destination. But that is always a possibility, even under ideal weather conditions. Something may have happened that closed the destination.

Worse, if the competence of the pilot stands in the way.

I often have the sneaky suspicion that the requirements for general aviation pilots are nowhere near the level that aspiring IFR pilots have to demonstrate for their rating here in Europe.

Oh, btw, I have absolutely no idea what an “LPV approach” is. Who is providing the vertical guidance? A surveyance radar approach (SRA)?

LPV is basically RNAV on steroids: in addition to GPS, the aircraft has a SBAS receiver (Satellite Based Augmentation System) that makes the GPS position more accurate. The approach then also defines a glideslope, but it’s not an ILS that keeps the aircraft on the glide path, but rather the LPV with the satellite based position.

In short, the flight computer knows where the aircraft is and where the glideslope is, and guides the aircraft from that—no ground-based navigation aids required.

I wonder if any of those affected by the power cut especially businesses sued the pilot. Even the power company for the cost of repairs, and not forgetting the rescue team. I imagine the total cost of this lack of judgment was very high. Maybe as high as the Mooney should have been! Chris ;)

Speaking of loss of visibility, JPL has announced the result of the investigation of the Mars helicopter crash (there’s a phrase I never expected to type!)

Anyway, the sand was too bland and featureless, so the camera navigation system lost the altitude and velocity reference.

This is going to lead to a multi-year suspension of flights on Mars.

It seems wild that someone can just decline to talk to the NTSB. In the UK, the accident investigation branches have pretty extensive powers to interview and get answers to questions.

In the United States, our constitution protects citizens from being compelled to interview or any form of inquiry from a governmental entity. Most pilots are willing to cooperate so this instance is unusual. Despite the constitutional protections, pilots are still subject to enforcement actions by the FAA depending on the facts.