The Pilot Turned Back: Engine Failure Leads to Fatal Crash

On the 26th of July a single-engine light aircraft crashed in the woods near Colbert, Oklahoma while attempting a forced landing. The pilot had reported his emergency ten minutes earlier and had the full support of ATC. The crash took place at mid-afternoon; it was a clear day and visibility was good. There was a number of fields around the crash site which were suitable for a forced landing. The pilot was instrument rated and had flown almost 1,500 flight hours.

That day, the pilot and his wife departed Jackson, Michigan in their Beechcraft Bonanza and flew to Springfield, Missouri, where they took on 45 gallons of fuel. They departed Springfield and climbed to their cruise altitude of 11,000 feet above mean sea level for a flight to Fort Worth, Texas.

About two hours into the flight, the pilot contacted Fort Worth Air Traffic Control Center and declared an emergency. The aircraft had lost power and he said that he needed to get to an airport right away. At that point, the aircraft was just over 8,000 feet and descending.

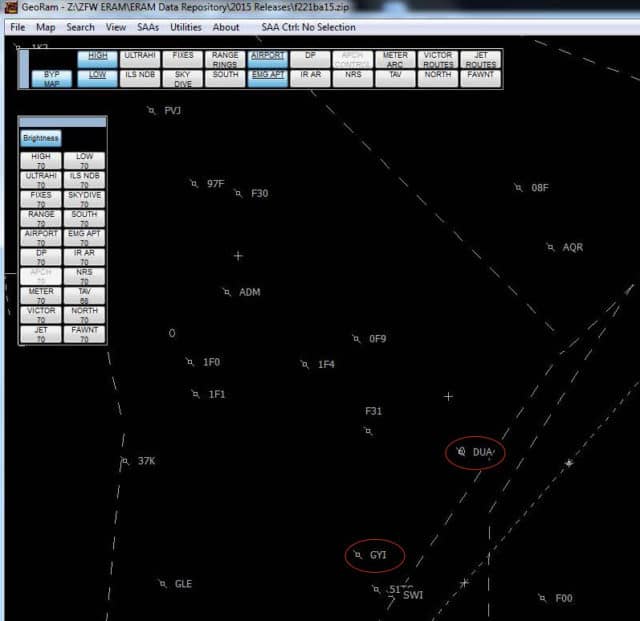

The controller told the pilot that North Texas Regional Airport (GYI) was at his 12 o’clock and about 15 miles (24 km) from his position. The pilot replied that he had partial power and he would see if he could make it there.

He asked the controller for vectors, which means that he wanted navigational support to get to North Texas Regional Airport. When vectoring an aircraft, the controller plans a route from the aircraft’s current position to the airfield’s landing pattern and then instructs the pilot to fly specific headings in order to follow that route. In an emergency such as this one, it means that the pilot can focus on flying the aircraft (or troubleshooting the problem) without the navigational requirements of diverting to the new airport demanding his attention.

The controller advised the pilot to turn to a heading of 245°. The pilot flew that heading for about two minutes, losing altitude along the way. As the aircraft descended through 6,000 feet, the pilot asked the controller if there was anything closer. The controller offered Durant Regional Airport (DUA) in Durant, Oklahoma, which was at the at the pilot’s 3 to 4 o’clock and 10 miles out.

In aviation, clock positions are used for horizontal directions, where the clock face is imagined to be lying flat with the pilot in the centre. When the controller initially told the pilot that North Texas Regional Airport was at his 12 o’clock, he meant that the airfield was straight in front of the aircraft. If an airfield was ‘at your 6 o’clock’ then it would be behind the aircraft. When describing the position of other aircraft, high or low can be added with reference to the horizon line: an aircraft at your 9 o’clock high would be to your left and above the horizon.

Saying that Durant airfield was at the pilot’s 3 to 4 o’clock meant that the airport was to the right and slightly behind the aircraft. This means that the pilot would need to turn right by just over 90° in order to change course to Durant. The pilot asked for turn information and the controller told him to turn right for a direct heading to Durant, meaning that from his current position, he could turn and fly directly to the airport as it showed on his map (and probably his GPS) and enter their landing pattern.

The aircraft turned right by 90° to end on a heading of due north (I would say 0° but the accident report actually says 360°. Possibly this is a regional variation?). Four minutes had passed since the pilot had declared his emergency. By now, the Bonanza was descending through 4,260 feet. At this point, the controller advised the pilot that there was a private airfield about a mile behind him.

“Wish I knew where that was,” said the pilot.

A private airfield can range from a grass strip on someone’s farm to a members-only aviation club offering fuel and other services. Private airfields almost always require prior permission if they are open to the public at all. However, most are registered with the FAA specifically so that an aircraft in distress can use the runway in an emergency.

The controller didn’t offer more information about the private airfield, however, instead offering the runway information for Durant Regional Airport, stating that the “minimum instrument flight rules altitude” for the area was 2,700 feet above mean sea level.

This seems to be a rather convoluted way to tell a stressed pilot in an emergency that he needs to stay above 2,700 feet to remain clear of obstructions until he has the runway in sight, especially as the aircraft was under partial power and descending. (Actually, now that I’ve written that, I’m wondering if he actually said minimum IFR altitude and someone expanded IFR for the report.)

Anyway, the pilot didn’t respond to any of this, instead wanting to know about the airfield behind him. “Where’s that private strip?”

“It’s not close enough for you to get to. There is GYI [North Texas Regional Airport] at your 2 to 3 o’clock, ten miles. Durant is at your 6 to 7 o’clock and ten miles.”

The pilot didn’t respond. But on the radar display, the blip representing the aircraft turned 180° until it was heading due south as it descended through 3,370 feet amsl. Then the southbound blip turned left and kept turning until the aircraft was at 270°, that is, the pilot turned three quarters of the way around to the left instead of just turning right. The aircraft continued to descend.

The last radar contact showed the aircraft near Colbert at 700 feet above mean sea level. The ground elevation in the area was about 660 feet: the aircraft was just 40 feet above the ground.

And then the blip disappeared completely.

Search and rescue personnel immediately travelled to the area where the aircraft last appeared on radar. At the same time, two witnesses contacted 911.

When I was pulling out of my parents’ driveway I heard what sounded like crunching metal. When I turned in the direction of the sound I saw what first appeared to be a car, yet upon further inspection I found it to be a plane. Only the pilot was visible. My neighbour’s wife then handed me her cell phone with 911 already on the line. I gave them the information they asked for then returned her cellphone. I attempted to give what aid I could when the paramedics arrived.

I was driving northbound on Winnett Road when I saw dust settling in the roadway and some debris laying in the road. I noticed the plane on the east side of the road and I proceeded to check the pilot for any movement. Then I heard the girl breathing deep from the rear of the plane and seen she was moving. I checked for pulse on the pilot and couldn’t find one so I waited for the paramedics to arrive.

The wreckage was found in the woods along the east side of a road. The Bonanza was upright and pointing south-south-west, the wings and fuselage scraped and dented from the tree branches. It wasn’t hard to recreate what had happened.

Still descending, the aircraft had crashed into the trees, the branches striking the wings and fuselage. A debris path of broken branches and aircraft parts stretched through the forest, including the engine cowling, the windscreen and the luggage. At the end of the path was an impact crater about 25 feet wide and 20 feet long containing the cabin, the engine, the propeller, the wings, and the rest of the fuselage.

The engine cowling and engine were all broken downward and twisted to the right by fifteen degrees. The nose gear was retracted; that is, he had not put down his wheels for landing, either because he wasn’t ready to land or because he didn’t want to use the wheels on rough ground.

The left wing was intact with dents and fractures along it. The left main fuel tank held 32 gallons of fuel. The right wing was broken at mid-span and the right fuel tank had broken open. Investigators reported a strong smell of fuel.

The forested crash site was surrounded by fields, any one of which would have been suitable for a forced landing. There was no pre-impact damage to the aircraft control systems. The ailerons and v-tail stabilators were still connected to the flight controls.

Under pressure and presumably panicked, the pilot seems not to have chosen a landing site but simply let the aircraft come down, possibly still hoping to find that private strip.

The propeller spinner was dented inwards. Two of the propeller blades were intact and undamaged and the third one was bent back to about 45° but had no leading edge gouges or chordwise scratches. This means that the propeller wasn’t turning on impact; the engine wasn’t running.

The engine was a Continental Motors model IO-520-BB which was sent to Continental Motors for inspection. They reported that the engine started without hesitation or stumbling and was run through various tests without issue. There was nothing wrong with the engine.

The aircraft had an engine data monitor installed which recorded the engine status every six seconds. By extracting the data from the monitor memory chips, the investigators were able to isolate the logs from the two flights that day and recreate the status of the engine.

The engine parameters all looked normal until the end of the flight. Nine minutes before the end of the recording, the exhaust gas temperature (EGT) dropped for all six cylinders from about 1,500°F to 400°F (from 815°C to about 204°C) and then to about 100°F. The cylinder head temperature (CHT) also dropped from about 380°F to 115°F. This was right about the time that the pilot contacted ATC.

Also in the wreckage was a laminated checklist which included a section for engine failure in flight. The fourth item on the checklist said: FUEL SELECTOR………………FULLEST TANK/OTHER

That is, check the fuel selector and set it to the fullest tank or simply to the other tank. The Bonanza has a fuel selector which allows the pilot to select which tank the fuel should come from, the right tank or the left tank. While flying, the pilot monitors the fuel and changes the tank regularly to keep them balanced, effectively manually balancing the load between two tanks. This is a common design on low-wing aircraft, where the fuel flow doesn’t gain help from gravity.

In an emergency, it’s standard procedure to change the tank which means that you can fix a temporary fuel blockage or unbalanced fuel if the fuel from one side is not, for some reason, making it to the engine.

As we saw in the description of the wreckage, the right tank had smashed open against the trees, so we don’t know how much fuel was in it but the smell of fumes on the ground when following the debris path imply that it wasn’t empty. The left tank was unharmed and close to full.

The fuel selector was set to the middle position, that is, between the right and left tanks. This effectively works as a shut-off valve. In this position, there is no fuel coming from either tank. There was no impact damage that would have shifted the fuel tank lever’s position. The tests and analyses showed that there was no problem with the engine and no issue with the fuel system. Investigators found no reason why the engine would not run other than that the fuel selector was blocking the fuel from reaching it.

It seems likely that the pilot accidentally set the fuel selector to the middle position during cruise flight, which stopped the fuel flow to the engine. Thereafter, he never checked the status and never switched the fuel tanks. This theory is backed by the fact that when Continental Motors tested the engine, it started and ran immediately. All it needed was fuel.

Probable Cause

The pilot’s failure to properly position the fuel selector, which resulted in a total loss of engine power due to fuel starvation.Contributing to the severity of the accident was the pilot’s failure to select an appropriate location for a forced landing, which resulted in the airplane impacting trees.

Contributing to the accident was the air traffic controller’s failure to provide the pilot accurate information on nearby emergency airport and airfields and the pilot’s failure to properly follow the airplane’s emergency procedures in the Pilot’s Operating Handbook that would have led him to properly position the fuel selector and restore fuel flow to the engine.

The pilot died on the scene. His wife died in hospital five days later.

When the pilot reported the engine failure to ATC he was 15.8 nautical miles from North Texas Regional and 7.5 nautical miles from Durant. At best glide, presuming 1,000 feet lost while he was getting the aircraft set up, he should have been able to travel 17 nautical miles, enough to make it to North Texas Regional and easily able to make it to Durant.

After declaring an emergency, the pilot flew for about 7.9 nautical miles before crashing which was plenty to glide to Durant if he’d gone that way in the first place. The private airstrip was the closest, just 6.2 nautical miles from his position when he contacted ATC.

So why didn’t the controller tell the pilot about Durant, which was the closer airport, from the very start? And what the heck happened with that private airstrip, which was actually only 6.2 nautical miles from his position when he contacted ATC?

I’m sure you won’t be surprised that there was a separate internal investigation at Fort Worth Air Traffic Control Center but what happened there will need to wait for another day.

In the meantime, you can read the NTSB report on their website: Final Report CEN15FA316

Poor chap.

I just wonder how many hours he had on this aircraft. Sylvia, you describe a system where the engine draws fuel from either the left OR the right tank.

Many aircraft have a selector that can be used from left, right or BOTH.

The position of the selector as you describe it makes me wonder if the pilot was under the impression that he had selected the ‘both’ position – shutting it off instead. Which could have been the case if he had converted to the Beech recently.

Then there is an additional clue:

‘Left, right and off not in same positions on all Bonanzas’.

Even though the pilot was reasonably experienced, this could have caused confusion. In the article, Sylvia mentions ‘their’ aircraft.I just wonder, how much time did this pilot have in this particular type?

BTW: Straight ahead (or north) is usually ‘360’. Easier to understand and less prone to misunderstanding than ‘0’

There have been enough accidents caused by this type of fuel selector where I’m surprised it’s still accepted on airworthy aircraft, let alone that it’s actually still being installed in newly manufactured ones. Having the fuel selector pass through any kind of “off” or “partially closed” setting as a matter of course while in flight is a DEMONSTRABLY terrible idea, and designing a selector where the intermediate position is BOTH, and OFF is a separate setting at the extreme end of travel is absolutely trivial.

Are there aircraft where fuel flow from both tanks is somehow bad or damaging enough to want to avoid even accidentally setting it?

I would modify fuel source controls so that you had to pull a sprung plunger in order to place the control in the OFF position. As long as no controls require that for L/R/Both positioning that would eliminate this as a source of inadvertent OFF selection.

The Cessna 172, at least the models that I used to fly, had a fuel selector on the floor between the two pilots’ seats.

The selector was very clear and unambigious: Selector forward, in the middle position: BOTH. Left: LEFT tank selected, valve right: RIGHT tank. Selector in the middle, facing rearward was OFF. That is nearly instinctive. If I remember correctly, take-off, approach and landing would be done with both tanks selected. During cruise it was recommended to fly on either left or right tank – switching at intervals.

Of course, the 172 is a high wing aircraft. The Bonanza, being low wing, does not have the benefit of gravity feed.

I do believe that at higher altitudes the “both” selection could lead to what is called “vapour lock”: fuel vapour could cause a disturbance in the regularity of the fuel flow and thus cause irregular engine performance. Stuttering, spluttering. Selecting either tank (assuming, of course a sufficient quantity of fuel !) would prevent it. I heard of it, but never encountered it. Not even in tropical Africa. so I looked it up and found something on a site called http://www.rpxtech.com which describes a similar occurrence in an older model C172. This one, thankfully, ended happily with a landing at an airfield and no damage.

I still wonder how much experience this pilot had on the Bonanza. His reactions to the situation, considering his total considerable flying time would suggest to me that he was not totally familiar with it’s idiosyncracies. Also, the Bonanza is heavier than the average light aircraft and would require much more attention regarding handling, especially in an emergency with a failed or failing engine.

PS:

I highly recommend that those readers of this blog who are active (or would-be active) Cessna 172 pilots read that article, maybe even print the accomanying procedures and bring it with them as an additional “Ermergency Checklist”.

A litany of errors. Surprised he did not head at least for an open field.

Rudy — I remember that fuel selector. (Got my private license in a C150, but my instrument rating in a C172.) Specifically remember that we were instructed (possibly placarded) to use only one tank above a certain altitude — some combination of vapor-lock issues and the fact that fuel flow would be lower if we leaned the engine properly after leveling off. IIRC I only had to do this once, when I flew above the New York City TCA (which topped out at 7000′ MSL) for the view and the direct line (in place of the snaky route ATC would have directed, including their ideas of adequate separation between commercial jets and something weighing well under a ton). I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised at the bad center-off design; I wonder whether the report includes a suggestion to require changing it, or even mentioning it as in https://fearoflanding.com/accidents/accident-reports/how-to-drop-a-gulfstream-iv-into-a-ravine-habitual-noncompliance/. (The link in Sylvia’s description downloads a file format I’ve never seen. Note that the Gulfstream accident had a stack of pilot errors, but the fact that the gust lock didn’t prevent the plane from accelerating was noted.)

Neil: we can’t know what the pilot was thinking — but if he was flying a hot/touchy plane (the reputation the Bonanza had when I learned to fly 45 years ago) that he may have not had much time in (per Rudy’s discussion) he may have tunnel-visioned on trying to keep the landing level (which it looks like he did) instead of cartwheeling after hitting at an angle. We also don’t know whether his passenger was panicking, which would have taken brainspace from thinking about options; the fact that he didn’t find the solution in the checklist despite 11,000 feet under him to read it doesn’t suggest focus on the issue (e.g., what was he doing for the 3000 feet he dropped before calling an emergency?). From what I’ve read, professional pilots do drills for all sorts of emergencies, which trains them to keep calm and work methodically toward a solution (having a backup in the cockpit to share the load with probably also helps); I don’t know whether any such training is available to private pilots. (Stall training and power cuts by an instructor are not substitutes because they can’t go to termination — and they would have been years behind this pilot.)

Panic and checklists are obviously not very compatible.

Chip, yes I agree with you. Somehow, somewhere it seems that this pilot somehow got “tunnel vision”, a fixation on one aspect of his problem.

Was it vapout lock?

Maybe.

We just don’t know what went on in the Bonanza during the last few minutes of his flight. Was he distracted by his passenger? We will never know.

Was he experienced on this type of aircraft? That can be ascertained.

One thing is for certain: Once the human brain goes into a panic, reason will be the first victim. In an aircraft this may be manifested by a fixation on one aspect of the problem and losing the ability to finding a solution by reasoning it out.

Many years ago, actually I think it was in 1969, I was working as a commercial pilot.

There were virtually no jobs for pilots. Banner towing was a way to keep the licence and earn a bit in the process. In the period between roughly 1955 and 1975 this was still good business. I did about 3700 hours flying advertsiing banners, mainly behind Piper Super Cubs but we also used C172 and other types. One company even used a Dornier Do28, a twin with STOL capacity.

My first employer was called Westdeutsche Luftwerbung Theodor Wuellenkemper KG. I believe it still exists as a cargo operator, now called “WDL Flugdienst”.

I got the job in an unusual way: After getting my CPL – basic, no IF nor ME ratings – I went to Hilversum where my aviation career had started.

It was 1969, Easter and that always attracted a lot of air advertising activities. There were two companies based there: One called Skylight, the other Luchtreclame Nederland, later Reclamair. In fact it was actually the start of the Dutch air charter comapny Martinair.

Reclamair was very busy that Easter weekend, they had even rented aircraft from other companies. In those days it was not unusual to have 20 or more banner towers in the air.

The chief pilot, whom I knew well, told me that he was not running a flying school. No work for a novice CPL.

But Reclamair had hired a few Super Cubs from WDL and the boss, Herr Wuellenkemper himself, was there to supervise his pilots.

I approached him, he told me that he needed pilots. So a weeklater I drove to Essen-Muelheim where they were based.

In Germany there had just been a change in the law that required that first officers working for an airline would need an ATPL. Which forced many German pilots to ask for a furlough and go back to school.

Many pilots who had a job flying light twins and who did have an ATPL filled their positions, it caused a surge for the few better jobs, leaving the bottom ranks: banner towing, sightseeing, photo flying, vacant.

Which, temporarily, opened those positions to be filled by Dutch and Norwegian pilots.

But even applying for one of those jobs I was promptly sent away by the chief pilot there, a Herr Pfannkuch.

But just as I was driving out of the gate he ran after me and called me back. They had just let one pilot go and I could start. Immediately.

Which in those days meant getting a German CPL with aero tow rating (“including in-flight object pick-up”) and I did two seasons there.

The pay was miserable: Basic pay 300 Deutsche Mark per month, plus DM 3 per flying hour. We often did more than 40 hour per week, so weather permitting we could earn DM 1500 a month. Gross.

Where is this going? I hear you ask.

Well, soon I was promoted to “Verbandsfuehrer” or formation leader. Which meant a basic pay of DM 500 a month and DM 5 per flying hour.

Nearly all flights were three aircraft and often there were 21 Pipers in the air, every day except Sundays. We were paid on the strength of a barogram, carried in the leader’s Super Cub. After flight, we had to bring it to the “Luftaufsicht”, this was not ATC because most of the guys in the control tower spoke no English. He would give ADVISORY instructions “Landen sie nach eigenem Ermessen” or “land at your own discretion”.

Anyway, the barograph would be opened, the barogram checked, stamped and signed after which a new roll would be entered, the ink replenished and the barograph sealed.

Some of the pilots were Norwegian. One had been a flying instructor and had been involved in a very nasty accident when his pupil, a sturdy fellow, froze at the controls during a spinning exercise.

The instructor was not able to overpower him and they crashed. I am not sure if the student survived, but the instructor still bore the scars of extensive facial reconstruction.

He had recovered and went back to flying. One of the very few jobs available was in Germany with the WDL.

He was in my formation when one day he reported engine trouble. We were not in controlled airspace and communicated using a VHF frequency assigned to our company. He reported fuel starvation.

The aim was to stay the maximum time up in the air. In order to do that, we took off on one tank, then switched to the other until it ran dry.

Then switch back to the still nearly full tank and finish the mission.

Somehow, this pilot got confused. His body had recovered from the crash, his nerves had not. We could see him losing height, then the engine would pick up again. Between us and a nearby airfield was a military area where they were shooting with live grenades. I called the military, asked them to suspend their artillery to allow an aircraft in distress to pass through. I told the pilot to drop the banner and we crossed the firing area. He landed safely.

I called the company. The chief pilot arrived soon after in another aircraft with a relief pilot. The banner was reovered by sending a car.

The cause was soon established: after running one tank dry, he (I won’t betray him by giving his name) switched first, correctly, to the full tank. But then, for some unexplained reason, back to the dry one. This he did repeatedly until he got totally confused.

This man had no doubt been a fine pilot. He had suffered an awful accident but had the guts to try and get back flying.

Before the chief pilot’s arrival I gave him a detailed briefing on the tank selector operation. He calmed down and I reckoned that the best course of action would be to allow him to complete the flight.

The chief pilot thought otherwise, put him in the passenger seat and the relief pilot took over.

This was of course an extreme example, but it does show how panic can take over and prevent the affected brain to function rationally.

This pilot was sent home. I don’t know if he ever flew again.

But there is a fine twist here:

This was a large operation for it’s kind of business. Up to 21 aircraft in the sky at any given time, 6 days a week, meant an equal number of pilots.

I was at the time the only Dutchman, there were some 6 Norwegians. In the weekend we would on occasion visit a local disco. Not often, we simply could not afford it, not on our salary.

But we met a few girls there and the Norwegian who was sent home has befriended a nurse there. She joined our group and we all chatted and danced.

When I saw her again, of course she wanted to know where her friend was. She had not seen nor heard from him for several weeks. I had to explain what had happened.

Well, we are already more than 48 years married. She is Irish, we live near Dublin.

Strange that the pilot didn’t have common software such as Foreflight or FlyQ or even a Garmin that would have instantly shown available airfields within gliding distance. It seems that he wasn’t focused on flying the aircraft as can be seen by the several mistakes made beginning with the failure to confirm his fuel selector position. While the selector may have a less than optimal design, it was the pilots duty to know it in his sleep. So, he blew that, then blew the engine out check list, then blew “finding an airfield”, and then chose to fly it into the trees. Incompetent to say the least. Scary that there are so many of these types racking up hours. One wonders who is passing them off as qualified pilots? RIP. I was hoping the wife lived.