The Cockpit and the Cabin: 2019 Incident at Stansted

We talk a lot about Cockpit Resource Management and the importance of the captain and the first officer acting as a team. A related issue which has had a lot less focus is the importance of communication between the cockpit and the cabin.

On the first of March 2019, an Airbus A320-214 registration OE-LOA suffered an engine failure before take off at London Stansted. There were seven crew on board and 169 passengers. The incident resulted in two passengers needing hospital treatment and ten passengers with minor injuries which were treated on the scene. The full details of the incident are covered in AAIB Bulletin 9/2020. For this post, I am focusing on human factors.

The Airbus A320 was departing London Stansted for a scheduled flight to Vienna. The flight crew lined up on the runway and the commander, who was Pilot Flying, applied full power for the take-off roll. The first officer called out “THRUST SET” but then, while travelling at a groundspeed of 31 knots, there was a loud bang and the aircraft veered left. The commander called “STOP STOP STOP” and rejected the take-off, coming to a halt between the centre-line and the left side of the runway.

The captain set the parking brake and used the public address system to alert the cabin crew by announcing “ATTENTION CREW: ON STATION” twice.

The first officer alerted ATC to the fact that they were stopped on the runway and completed the actions for ENG 1 FAIL and ENG 1 REVERSER UNLOCKED messages on the electronic centralised aircraft monitor. There was no indication of fire. The commander shut down the left engine and contacted the Rescue and Fire Fighting Services, asking them to confirm that there were no signs of fire visible from the outside.

The Rescue and Fire Fighting Service arrived quickly and reported that there was no sign of fire. The flight crew agreed that they would vacate the runway using the thrust from the right engine and contacted ATC for clearance to do so.

So far, this is all standard procedure, except that in the cabin, things were not going as expected.

There were five cabin crew on board that day. Soon after the take-off roll, they heard a loud noise and felt the aircraft drift to the left before coming to a stop.

Four of the cabin crew heard the captain call ATTENTION CREW: ON STATION. This command is meant to alert the cabin crew that there is an emergency on ground. Upon hearing this announcement, the cabin crew are to move to their doors and remaining on high alert, waiting for additional commands from the cockpit.

The Senior Cabin Crew Member, who was at the front of the cabin, heard the loud bang and felt the aircraft veer to the left but did not hear the captain’s announcement.

The second cabin crew member, referred to in the report as FA2, stood and looked out of the left forward cabin door window.

At the rear of the aircraft, FA3 heard the bang and saw red and yellow lights through the passenger windows. FA4, stationed at the left-side rear exit, was the most experienced of the cabin crew. She reassured him and the fifth crew member, both newly qualified, and advised them to stay calm and wait for instructions from the flight crew. FA3 and FA4 stood at their assigned exits.

The fifth cabin crew member was on a familiarisation flight having completed training and was not assigned an operational role. As there didn’t seem to be any danger or immediate urgency, the additional cabin crew member did not take any action but waited for further instructions from the flight deck.

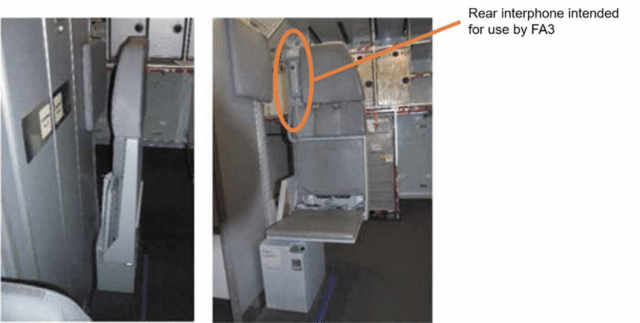

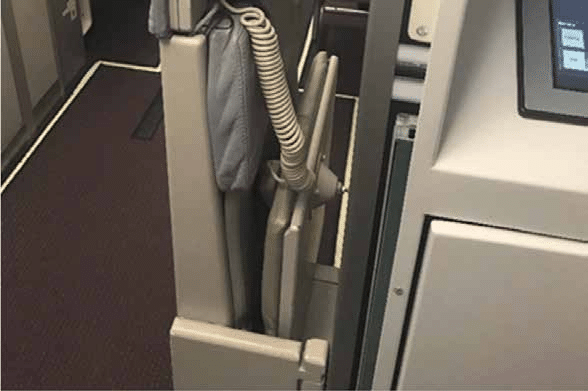

There are three interphones in the cabin which the cabin crew use for communication: one at the front and two at the rear of the aircraft. One of these is attached to the rear aisle swivel seat which folds into the wall; when opened and locked in position, it provides a forward-facing seat for a cabin crew member. When FA3 stood up, he lifted the release latch for the seat, which allows the seat to automatically fold back into the stowed position. However, as the seat folded, the interphone handset fell out of its cradle and the cable became trapped in the folded seat.

This happened a lot with these phones, apparently, although no cabin crew member had ever reported it. The FA3 remained standing, looking out the right-side door to see what was happening.

The Senior Cabin Crew Member at the front of the cabin was not sure what was going on but she stood up when she saw the other cabin crew standing at their exits. She said later that she felt shocked and overwhelmed and that all of the passengers were looking at her.

She picked up the interphone to check with FA3 at the rear of the aircraft that everything was OK. However, FA3 hadn’t placed the interphone back on the cradle and the cable was still trapped, which muted the sound of the chime.

The Senior Cabin Crew Member tried again to contact FA3, explaining afterwards that she was trying to work out whether an evacuation was necessary. As FA3 was not responding, she switched to the public address system, saying “Can you hear me?”

This got FA3’s attention. The Senior Cabin Crew Member attempted to communicate with him via hand signals but the cabin lights were not on and she couldn’t see well enough to understand the signals he was making. She could not see that the interphone was trapped.

FA3 finally freed the interphone so that he could speak to her. He said later that after the captain’s announcement, a few seconds felt like minutes, because none of them knew what was happening.

The Senior Cabin Crew Member said that both of the cabin crew at the rear of the aircraft looked scared and shocked. She understood FA3 to say that he had seen flames and sparks from the engine.

That’s the information she was looking for and she announced “EVACUATE, EVACUATE, EVACUATE” over the interphone. FA3 didn’t understand why she would be commanding an evacuation over the interphone. He told her she should announce it over the PA system, which she then did.

Normally, an emergency evacuation is initiated by the captain, using the public address system. However, if there is no evacuation command from the cockpit and there is no doubt that an evacuation is necessary, a cabin crew member can initiate an evacuation. The situations under which a cabin crew member can carry out an evacuation are specifically listed:

- Immediate danger (fire, smoke, explosion, water, etc)

- Cockpit crew is incapacitated (injured, not on board)

- Communications down due to heavy damage to aircraft

After the event, the Senior Cabin Crew Member confirmed that she knew the guidance but also that she wasn’t thinking about it at that moment. She didn’t think to contact the flight crew. She said that she didn’t have much contact with the pilots and only a limited understanding of their responsibilities in an emergency. “For me,” she said, “it was the door closed, I have nothing to do with them.”

One minute and twenty seconds had elapsed between the “ATTENTION CREW: ON STATION” command by the captain and the “EVACUATE” command by the Senior Cabin Crew Member.

Meanwhile, FA3 never saw any signs of fire and says he never told her that there were flames and sparks outside. But FA4, who was across from him at the left-side rear exit, said that she also thought she heard him saying that he’d seen fire outside. She then heard him tell the Senior Cabin Crew Member to repeat the evacuation command “out loud”. She tried to contact the Senior Cabin Crew Member via the other interphone but got no response. She then heard the Senior Cabin Crew Member repeat the “EVACUATE” command over the public address system. She hesitated for a moment but when she saw that FA3 was already opening his door, she opened her door in order to evacuation the passengers.

The passengers reported later that the cabin crew seemed to be having problems communicating, shouting in English and German and using hand gestures before using the public address system to speak between the front and back of the cabin. Four of the passengers said that they never heard or did not understand the command to evacuate.

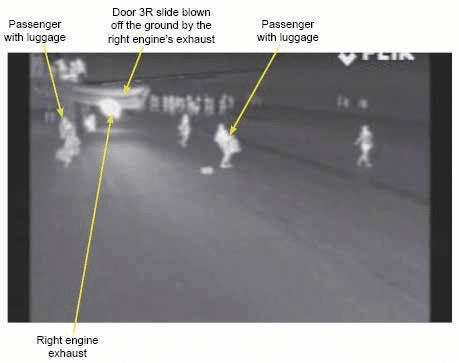

When FA3 opened his assigned exit, the right hand door at the rear of the aircraft, the inflated escape slide was floating almost horizontally instead of resting on the ground. He had no idea why the escape slide hadn’t extended correctly, however it was clearly unsafe, so he blocked the exit. Both cabin crew members called out evacuation commands to the passengers and helped them disembark through the left-side door. They took hand luggage away from the passengers attempting to carry it off the plane, piling the luggage by the right-side door.

The aisles became blocked as people attempted to take their baggage from under their seats and from the overhead bins. Other passengers shouted at them to leave their luggage behind. Passengers exiting from the overwing exits, which were not manned by cabin crew, were seen on CCTV leaving the aircraft with their baggage. One passenger estimated that about half of the passengers took their hand baggage with them.

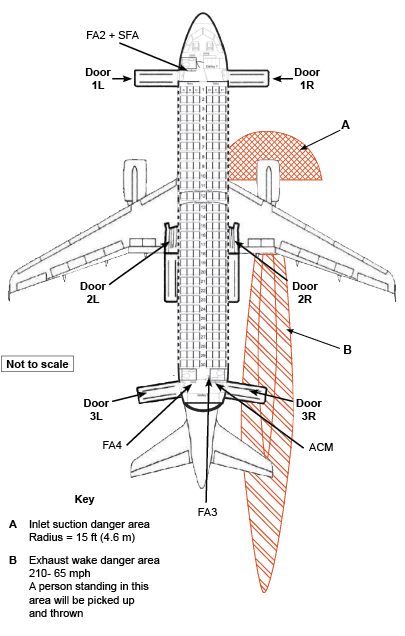

At the front of the cabin, both exits quickly became blocked as the cabin crew attempted to take the hand luggage away from the passengers. The passengers leaving via the slide at the front right-side of the aircraft were subjected to jet exhaust from the right engine, which was causing “wind speeds” of 65 mph and greater. Some passengers were blown over several times and others had their belongings blown away.

Once the passengers had all been evacuated, the cabin crew checked the cabin. FA3 asked the additional crew member to disembark and help him assist the passengers on the ground, planning to follow her down.

Back in the cockpit, the flight crew had informed ATC of their intention to vacate the runway using the thrust from the right engine. Just as the captain was about to make an announcement for all cabin crew to return to normal operations, he saw a caution message on the ECAM (Electronic Centralized Aircraft Monitor): DOOR L FWD CABIN was lit up in yellow. He initially assumed that the notification was a fault with the left forward cabin door sensors. Looking out the left window, he saw the evacuation slide had been deployed out of that door and worse, a passenger was crossing in front of the aircraft.

He called the Senior Cabin Crew Member and, according to the report, he “asked her why the evacuation had been initiated” … although I’m pretty sure that is not quite the phrasing he used! The cabin crew member replied that she believed he’d ordered an evacuation.

After making it clear that he had not, in fact, ordered an evacuation, he realised that there were passengers on the right side of the aircraft, near the running engine. He started the APU (Auxiliary Power Unit) and shut down the right engine. Three minutes had passed since the shutdown of the left engine.

Once it became clear that there was no reason to evacuate, FA3 disembarked to find the additional crew member who he had sent down to help the passengers.

I can’t help but imagine the conversation in the cockpit. One the aircraft was safely shut-down, the first officer went into the cabin to find out what had happened.

The cabin was empty except for three cabin crew. Piles of abandoned baggage were piled by the exits. The first officer asked the missing cabin crew members to return to the aircraft. There really wasn’t much else that anyone could do.

If you are wondering about the "incident" at #Stansted: a plane was stopped just before getting on the runway because of an engine failure.

Everyone is ok, we are on a bus waiting to get back to the Terminal. pic.twitter.com/7f1IvCi8dG— Chiara Nardi (@chiara_nardi) March 1, 2019

Local ambulances quickly arrived on the scene. Two passengers were injured and were taken to hospital. Ten passengers were treated for minor injuries on the spot: cuts, grazes, bruises and sprains.

The Airbus A320 was towed off of the runway to a remote parking position. The airline organised a replacement aircraft which flew the scheduled flight to Vienna later that evening.

From the AAIB Bulletin:

Once they had noticed that an evacuation had commenced there was realistically no way that the flight crew would have been able to recover the situation. It may have been prudent to action the EMER EVAC checklist to ensure that the aircraft systems were all in as safe a state as possible for the passengers to exit the aircraft. However, given that passengers were potentially going to encroach into the right engine’s inlet suction danger area it was probably quicker to select the eng master to off. Had the commander prioritised shutting down the engine and thus had a more succinct discussion with the SFA, the right engine could have been shut down sooner.

I can’t help but think that it is asking a lot of him to have the presence of mind to cut off the “You did what???” conversation in order to shut down the remaining engine but it’s clear that those exiting from the front right engine were at real risk of being sucked into the engine.

Any of the cabin crew could have contacted the cockpit at any point but their training had not supported interactions with the flight crew. The cabin crew knew the pilots would be busy in an emergency but they did not have any understanding of what the pilots might be doing up there or how long it would take. As a result, although they only spent just over a minute waiting for an instruction, it seemed like a very long time.

The Senior Cabin Crew Member, in particular, should have contacted the flight deck as she had not heard the announcement. However, it had never occurred to her to contact the pilots. As far as she was concerned, she was on her own. She had qualified as a cabin crew member in May 2017. The six week training course was designed for 20 to 25 trainees but on her course, there were 39 trainees. The airline went bankrupt at the end of that year and she did not fly for three months.

The new operator who took over the airline was under pressure to have trained staff available for flights and in May 2018, she completed a five-day classroom-based (theoretical) SFA course and was promoted to Senior Cabin Crew Member. Between the large group in her initial training, her low amount of practical experience and the intensive theory training compacted into just five days, she was clearly lacking in the skills and judgement required of a Senior Cabin Crew Member.

All of the cabin crew had trained for evacuations following an emergency. However, every emergency that they simulated included a practice evacuation. At no point had they practised returning to normal operation — as far as the training was concerned, emergencies ended in an evacuation.

I’ve focused on the cabin crew here, however if you are interested in other issues raised by this incident, it is worth reading the conclusions of the AAIB Bulletin 9/2020. The report deals in detail with the causes of the engine failure, which I have skipped over, as well as the emergency response and problems with the interphone.

The report also spends a fair amount of time on the fact that many of the passengers collected their bags, intending to leave the aircraft with them, which slowed down the evacuation. Luggage was taken away from the passengers disembarking through the manned exits but this left the cabin crew needing to find a place to store the bags without causing an obstruction. Studies have shown that this compulsion to take the luggage in an emergency is not overcome by briefings and instructions and, in fact in one case, even trained flight crew attempted to take their baggage with them in an evacuation. The bulletin quotes the Royal Aeronautical Society, which recommends that the overhead bins which do not contain emergency equipment be locked remotely, before making two Safety Recommendations.

Safety Recommendation 2020-018

It is recommended that the European Union Aviation Safety Agency commission research to determine how to prevent passengers from obstructing aircraft evacuations by retrieving carry-on baggage.

**Safety Recommendation 2020-019**

It is recommended that the European Union Aviation Safety Agency consider including a more realistic simulation of passenger behaviour in regard to carry-on baggage in the test criteria and procedures for the emergency demonstration in CS-25.

CS-25 is the regulation which requires that all crew and passengers can be evacuated within ninety seconds and airline operators must demonstrate that they can meet this requirement in the dark with minor obstructions. However, the simulated evacuations do not, at present, require the further complication of passengers attempting to retrieve their baggage and leave the aircraft with it.

The operator has taken several safety actions, principally based around the training of its flight attendants.

These changes include the requirement for the cabin crew to at least try to contact the flight crew before commanding an evacuation.

As a quick, initial reaction: It seems to me that the training of the cabin crew in this airline is not really of the highest standard. Also, the call from the cockpit “Attention, crew on station” seems to have been in accordance with the company’s SOPs, but the phraseology has the potential of confusing matters, rather than conveying a clear instruction. This was in all reality a minor incident, apparently well handled by the flight deck crew. But in the aftermath of the sudden need to stop the aircraft, keep it under control, deal with ATC and the emergency checklist – all simultaneously – the procedures should be clear and easily understood.

The cabin crew did not work well together either. No, the airline did not cover itself in glory. Training of flight crew is an expensive matter, but the role of the cabin crew in an emergency is a serious one and not something that can be skimped on.

Yes, that’s what intrigued me about this case is that the actual incident was all handled quickly and cleanly and yet there were twelve injuries. But I think the lack of training for the cabin crew, especially the (unlucky) combination of the cabin crew member in an overfull class for her initial training, on the ground for an extended period when the airline didn’t fly, and then finally in a rushed bare-minimum theoretical course for her position as SCCM is one of those “holes lining up” moments where she didn’t really know what to do in an emergency and probably started panicking at the point of hearing the loud bang.

But also, the fact that the airline made no effort to integrate the cabin crew and the flight crew surprised me — Anna told me about BA training and that definitely was something that was considered important.

I’m not surprised there were injuries; I’ve heard of injuries at other evacuations even without the hazard of a running engine. I suspect those inflatable slides get steeper, curving when somebody is actually on them rather than letting the rider down smoothly; ideally there would be a crew member at the bottom assisting (and making sure passengers clear the slide quickly), but it doesn’t sound like there were enough crew for this.

I’m not surprised at the lack of integration; I’d never heard of Lauda before this incident, and Wikipedia tells me they’re small enough that Ryanair could buy them. I’d expect they were cutting a lot of corners in order to make money while it was makable on low fares — makes me wonder what would have happened if there’d been problems in the days I was riding People Express.

But have you watched Rush? https://g.co/kgs/5TXM9q

Niki Lauda has been in the air travel business since 1979, with “Lauda Air” and “niki” before “Laudamotion”. Laudamotion/Lauda is basically “Ryanair Austria”.

Flight attendants nowadays could simply wear headsets. Modern aircraft systems are radio-safe, and using headsets means the atrendants can easily contact each other or be contacted by the pilots no matter where they are on the aircraft (e.g. attending to injured passengers, see the post a few weeks ago). Using wired handsets feels antiquated and should at best be a backup solution.

If all the pilots need to do is flip a switch to talk to the attendants, they could be trained to keep them in the loop more.

To be fair on the flight crew, it’d been less than ninety seconds since they called the flight crew to attention; if the SCCM had heard the first call, she probably would have waited longer before reacting. Although I brought up both, I think this is much more about inexperience than lack of communication; although the interphone issue didn’t help.

I wonder about the headsets — it’s another thing to go flying off, is the first thing that comes to mind. How to set it up without risking ear injury to the cabin crew? But it does seem like an obvious upgrade.

If the crew operating a fast food place can work with headsets, I expect a cabin crew can, too. Though, admittedly, burger joints rarely undergo crash landings.

Exactly Sylvia’s point — headsets would be most dangerous when most needed. I suppose something like modern phone buds-and-mike would be unlikely to hurt someone — but they’d need to come with a press-to-talk switch so cabin crew wouldn’t have each others’ talk to passengers filling up their ears during normal flight. I don’t think there’s any solution that doesn’t require practice to get used to.

I’ve thought for many years that remote locking of overhead bins would greatly aid evacuations. I guess it comes down to a cost/weight element, plus extra things to go wrong in normal operation. Does anyone know if it has been seriously considered?

The remote locking is definitely being seriously considered, especially as planes are developed to hold more and more luggage. Maybe I’ll do a piece on the Royal Aeronatical Study that focused on this, it’s interesting.

Modifications to aircraft are always costly. Mendel’s suggestion is interesting. Remote locking may raise as many problems as they solve. Yes, I agree with Colinto that in theory it would expedite an evacuation, but I fear that reality will prove to be different.

In quite a few – too many – actual evacuations passengers were blocking the aisles because they were unwilling to leave the aircraft without their belongings. If the overhead lockers were to remain shut, they may just keep pulling to force them open. Of course, they would endanger their life and the lives of other passengers but it happened. The civil aviation authorities would have to approve such a modification. The travelling public would have to get used to them and, if only one airline decides to introduce such a system, the cost of installation would be prohibitive, especially if it were to be a retrofit.

Right now, the best solution seems to be better, more focused training of the crew, especially on the subject of teamwork. Perhaps a re-write of some SOPs should be considered. If that has not already has taken place. One factor that always has been the basis of the high standard of air travel safety is the willingness to examine whatever went wrong, learn the lessons and implement them.

Locking the overhead bins should occur at the same time the “fasten searbelt” sign goes on. It would perhaps add another level of safety in strong turbulence, where overhead compartments have sometimes opened (due to broken latches), and falling luggage has injured passengers.

I wonder: the senior cabin crew member thought that one engine might be on fire. This would normally be a good reason to not evacuate on the side of the fire, wouldn’t it? But that didn’t happen here. The evacuation announcement via the phone was another indication that the SCCM wasn’t thinking straight at that moment.

It looks to me like that person simply panicked in that moment; and to address that, you need to train how to cope with panic in yourself: to recognize it, and to gain a clear head again before committing to any action, and how to support yourself and enlist the help of others to that end.

I’d expect that flight attendants are trained to deal with panic in passengers; they should perhaps be able support each other in that event. But you then run into the same issues that we know from CRM: how much courage is required for a flight attendant to tell their senior that they’re panicking, and suggest a different course of action?

Mendel’s suggestion of centrally locking the overhead bins, yes it does have merit and should be considered.

But I still am of the same opinion: It should be made mandatory. That also means that older aircraft must be retrofitted, otherwise the public will continue to try and force the bins open in aircraft that do have the modification. It will require a certification process that is more than likely going to be lengthy, because the legislation in all countries will have to be adapted. Airlines will not like it. Many are already on the brink of collapse, an extended period during which the entire fleet will have to be modified (even if one by one) is going to be expensive. The current period would just be ideal, since air travel has shrunk to less than 30%. Boeing still has nearly its entire Max fleet to be delivered.

At this very moment, when airlines and manufacturers are looking bankruptcy in the face, it does not look likely that government agencies, manufacturers and operators will coordinate and agree to implement a costly program. How many people employed in the airline- and related industries have already been made redundant? I know quite a few pilots, some were former first officers when I was captain on the old Fokker F27, who now got commands in high-paying jobs, flying Boeings, Airbuses, now unemployed. Ground staff, ditto. The manufacturers? Scorched earth. Even air traffic control jobs have seen hiring stops. A program that will require a hefty investment is the last thing they want. Maybe it will need another catastrophe, one that should have been totally survivable. A disaster in which many people die unnecessarily because aisles and emergency exists are blocked with luggage, and people frantically trying to save their belongings. Causing the death of fellow passengers and perishing themselves – with their precious luggage.

Just to come back on the first comment that Sylvia inserted: Lauda Air is a small airline, founded by the late F1 racing car driver Niki Lauda. The company was bought, a few years ago, by Ryanair but operates as an independent carrier, just like Aer Lingus that was absorbed into the BA family but retains its identity.

When I was a captain with Ryanair it was a small company. They started with one Bandeirante, then expanded with the 748 soon replaced with a handful of BAC 1-11s. We did our ground training in an aircraft. Staff, including ground staff and office workers, volunteered for the drills. We were in the cockpit, cabin full of people and the cabin crew with trolleys in the aisle. When we were given the signal, we had to initiate the process: An announcement that we were about to make a crash landing, the cabin crew had to store their trolleys, get the “passengers”, the volunteers, ready followed by “brace for impact” and the command “evacuate, evacuate”. The doors and escape hatches would be opened and the slides inflated, followed by the evacuation. We were to monitor the process and subsequently use the ropes to exit via the cockpit windows. I was lucky because I was still under training and occupied the first officer’s seat. The captain had to be careful because am icing probe stuck out of the side, not far from the left cockpit window. It did not always go flawlessly, on one occasion we had to call the ambulances because a girl had come off the side of the slide and broken a leg. I suppose that Ryanair now has a more sophisticated training centre. KLM had a large facility, a cabin mock-up with galley. Taped messages would give instructions to store galley equipment, the whole thing would rock violently, the lights would go out and it was possible to pour smoke into the mock cabin. The “passengers” would have to use the floor lighting to crawl to the exits. One side would give access to the floor below, to be reached via the slides. Exiting by the other side meant that we would plunge into a pool, inflate our life jackets and swim to life rafts. Getting in was not easy and we were expected to assist “survivors” getting in.

This all goes to illustrate that airlines in general do take cabin safety very seriously indeed, and cabin crew are being trained to a high standard. But of course, larger airlines own, or have easy access to training facilities that small operators can only dream of.

But in the case of this incident I do not think that the crew were trained to the highest standard, and periods of furlough did not help either.