The aftermath of the An-12 crash on approach to Lviv

Last week, we discussed the Antonov An-12 crash on approach to Lviv. I’m going to assume you’ve read that article (and the comments, which highlight some of the key aspects that jumped out at other readers). This means we can pick up the sequence from the final report again at the point when the Antonov An-12 registered UR-CAH crashed into the high terrain just under 1.5 kilometres from the runway threshold of Lviv runway 31.

In the Lviv Tower, the controller had cleared the flight to land, which had been confirmed by the flight crew of the An-12 at 03:42:06. But the minutes ticked past and at 03:45:30, when the controller had still not seen any sign of the inbound aircraft, he attempted to contact them to find out where they were. He got no response. He continued to call the aircraft and at 03:48:33 he reported to the CDA that he had lost contact with the plane. Thirty seconds later, he announced an emergency via the loudspeaker that an An-12 had been lost on landing approach between the second kilometre and the runway threshold.

The rescue teams immediately began to acknowledge the emergency. The CDA controller contacted the Tower controller to ask whether the “Emergency” signal was announced and whether rescue teams should be gathered. He told her yes.

Now CDA isn’t defined in the report, although it has very clear responsibilities during an emergency. The Tower must announce the Alarm to the rescue teams and to the CDA. The CDA then “duplicates the signal” and as the rescue teams confirm, the CDA records the time. The head of the rescue operations maintains contact with the CDA and it is up to the CDA controller to report the accident to the State Emergency Service, the Lvlv Regional Centre for emergency medical aid, the support centre for search and rescue and “other interested organisations”.

The Tower controller repeated the emergency signal:

“To emergency rescue team – Emergency for aerodrome, to emergency rescue team: Emergency, Emergency! An-12 disappeared at a distance between the second and the first kilometre, at 03:47…3:45 pm, communication was cut off, heading 310.”

The controller did not know where the aircraft had crashed so was not able to give a grid location for the rescue teams. She also did not know the number of crew members on board or if there were hazardous materials on board.

The procedure for a crash where the location is not known is for the rescue teams to meet at the grid location 8Zh on the aerodrome map. At 04:06:55, the tower controller asked the CDA official if they were searching for the aircraft and the CDA official said that the rescue teams were being collected at the B1 parking place. B1 is within the 8L grid location.

The Tower controller contacted the CDA again at 04:25 with a list of search squares for the possible location of the aircraft, believing that the crash likely happened in the area of 19-C-C or 20-T-T.

The shift supervisor, who was also the head of rescue operations, decided instead to start the search in square 18-P-P.

At this stage, “no later than 15 minutes after receiving the information about the incident”, The Emergency Plan specifies that the airport management should contact the aviation authority about the accident. This did not happen. In fact, the aviation authority learned about the accident when it was broadcast on the news.

The final report by the National Bureau of Air Accidents Investigation of Ukraine starts with the following:

The NBAAI was not informed about the fatal accident by the Lviv aerodrome operator, the airline operating the aircraft and ATS unit. The NBAAI received preliminary information about the crash from the mass media and made a corresponding request to the State Aviation Administration.

Meanwhile, at the same time that no one was notifying the NBAAI about the crash, the search and rescue teams had gathered and began their ground search.

The shift supervisor, who was also the head of rescue operations, decided to start the search in square 18-P-P. The ground search was complicated by thick fog and the terrain, with dense bushes and trees blocking the route to the likely area of the aircraft·

Almost an hour after the Tower controller had announced the emergency signal, the searchers heard voices from the injured victims in the crash. Five of the crew were dead, with two bodies in the cockpit and three on the ground near the wreckage. The voices were coming from inside the An-12.

The search and rescue team used electric circular saws to cut through the aircraft fuselage where they could hear the voices. They pulled out the cargo and found two members who were conscious but unable to move. They injected the two crew members with anaesthetic before dragging them out to the medical team. The third surviving crew member was found soon after. They were able to extricate him from the wreckage in order to offer him medical attention.

Once they were stable, the three crew members were asked to share their recollections of the crash.

The flight engineer was able to recall that at 03:00, during the approach, he was in the cockpit section on the left, sitting at the table with his back to the nose of the aircraft. There was someone else sitting at the table, facing him. It was this person and the table which crushed his abdomen, lower chest and legs in the impact. When he attempted to make his own way out of the wreckage, he broke his right arm.

The avionics maintenance technician remembered that he was in the seat to the right of the cockpit, facing the flight direction. He was not sure what had happened but believed that he was pressed between the seat and the kitchen panel. He had various bone fractions and a head injury.

The aviation technician said he was sitting at the table to the left, facing the flight direction. At the moment of impact, the table twisted into a vertical position and he was trapped between the chair and the table. His chest was crushed such that he struggled to breathe and his legs were twisted beneath him.

All three of the survivors were seated and with seatbelts on at the time of the crash.

The remaining crew members were the captain, the first officer, the navigator, the flight engineer and the flight radio operator. All of them were listed with the same cause of death:

blunt concomitant body injuries as a result of shock-inertial impact from contact with blunt objects and blunt instruments with a limited surface resulted from the destruction action at the time of the aircraft impact.

That is to say, they died in the initial impact.

There was no sign of ethyl, other alcohols or narcotic substances. There was no evidence of any physiological factors or disabilities which might have affected the crew members’ performance.

The report describes the wreckage:

- The cockpit was completely destroyed.

- The front landing gear was destroyed.

- The left outer wing (fuel tank) was destroyed.

- The leading edge of the wing was destroyed.

- The wing flaps were destroyed.

- Propeller No. 1 received substantial damage (from left to right of flight direction).

- Engine No. 1 suffered substantial damage.

- Propeller No. 2 received substantial damage.

- Engine No. 2 received substantial damage.

- Propeller No. 3 received substantial damage and separated from engine # 3.

- Engine No. 3 received substantial damage.

- Propeller No. 4 suffered substantial damage and separated from engine # 4.

- Engine No. 4 was destroyed.

- The right outer wing (fuel tank) was destroyed.

- The right landing gear was destroyed.

- The right landing gear fairing was destroyed.

- Underfloor fuel tanks were destroyed.

- The stabiliser leading edge received substantial damage.

- The fin received minor damage.

- The control panels of the aircraft systems, aviation instruments and network circuit breakers were completely destroyed.

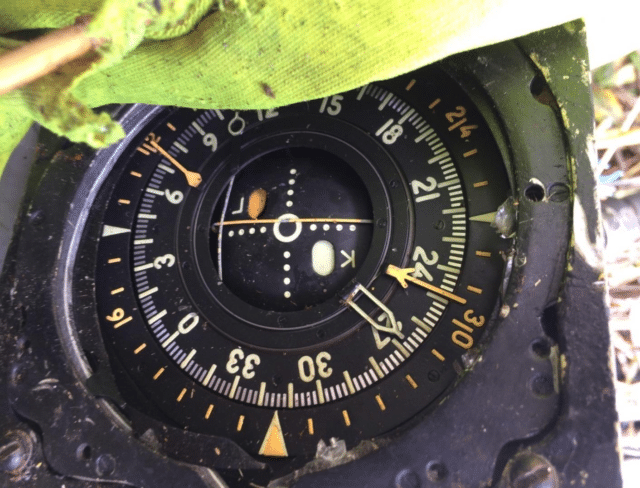

The investigation found the remnants of the aircraft instrument landing system among the wreckage. The glideslope and the heading alarm flags were turned off.

The cockpit voice recorder showed an issue with the EGPWS (extended ground proximity warning system). It sounded at 02:01:43, calling out “50…30…MINIMUMS. MINIMUMS.” At that point, the aircraft was at level flight at FL250 (25,000 feet). However, when the aircraft was descending for final approach, the EGPWS system did not give any warning before the An-12 crashed into the ground.

No other issues were found with the aircraft systems: the engines were operating normally and the engine parameters consistently matched the operating modes set by the crew. The propellers were fully maintained and serviceable. All maintenance records appeared correct.

There was no fire and the fuel tanks had remained relatively intact. The remaining fuel was drained from the aircraft as a part of the investigation. They discovered that the only fuel remaining was in the wing root tanks, about 170 litres of fuel.

This is important because that was not enough fuel for the An-12 to fly to their alternate airport of Boryspil. The crew never discussed the issue but they were committed to landing at Lviv; they did not have the fuel to divert.

The operational flight plan listed the aircraft as having a take-off weight of 61,000 kilograms on departure from Vigo; however, the investigation team found it difficult to verify this number.

There was no flight assignment, no logbook entry and no record of the crew’s calculations of take-off weight and the An-12’s centre of gravity.

The Charter Cargo manifest listed the gross weight of the cargo as 13,000 kilograms. However, another consignment note listed the gross weight of that same cargo as 14,078 kilograms. Investigators contacted the airport handling company at Vigo to clarify the actual weight of the cargo loaded, however they were told that the company did not have any documentation on the actual cargo.

Based on an estimate of the amount of fuel taken onboard, the investigation team found that the take-off weight must have been between 65,500 and 67,500 kg, which would make it 6.5 tons heavier than the maximum take-off weight for the An-12B, which is listed in the flight operation manual as 61,000 kg. Note that this maximum take-off weight also just happens to be exactly the weight listed on the operational flight plan.

This explains what happened when they took off at Vigo. I wrote:

The Antonov An-12 manual states that the aircraft should “unstick” at 240 km/h with a take-off distance of 1,230 metres, after which it will climb away at 2.3 to 3.3 metres per second.

The flaps should be fully retracted once the climb is established, with an altitude of at least 150 metres and a speed of 310 km/h.

But that evening at Vigo, the An-12 unstuck at a speed of 272.3 km/h after a take-off distance of 1,600 metres, climbing away at a rate of 2.76 metres per second. The flaps were gradually retracted to 5° and only fully retracted at an altitude of 6,600 metres (21,000 feet).

That sounds very much like an aircraft that is overweight and more to the point, like it is being flown by flightcrew who are aware that the aircraft is overweight.

There are still a lot of questions but a scenario starts to come together. First, we have inklings of a management culture that expects flight crew to get the job done with many last minute changes and without ensuring rest periods. Most of the flight crew had been working beyond normal hours and must have been fatigued; nevertheless, they remained on the site to prepare for the next leg of the trip, without having any opportunity for rest. Their mental and physical performance would have been impaired.

Then, the captain took the decision to continue the next flight, despite his fatigued crew and the adverse weather conditions at his destination. The crew working hours does not appear to have figured into his decision. The details of the cargo and the loading of the aircraft were badly documented and the weight of the An-12 was simply listed as the max take-off weight, even though the aircraft itself was quite a bit heavier.

The heavy An-12 would have burned much more fuel than planned as a result of being overloaded. By the time the aircraft and crew arrived in the vicinity of Lviv, they did not have enough fuel to divert to their alternate airport.

One issue is that on the forecast used by the crew, the fog and low visibility was listed as a TEMRO, a temporary deterioration, which the flight crew don’t need to take into account on departure for an IFR flight. I’m not sure about TEMRO but a TEMPO, as used for aviation weather forecasting, is meant for weather conditions lasting for 30 minutes but less than 60. The variations should be short or infrequent enough that the conditions can be considered to be the forecasted weather which proceeds the TEMPO, in this case, visibility 3000 metres with broken clouds at 210 metres. Those conditions would have been fine for the approach to Lviv.

If the estimated arrival time coincided with a decrease in visibility because of a change in weather conditions (BECMG), then the lowest value has to be taken into account. In this case, the forecast had a TEMRO between 18:00 and 06:00 of fog and low visibility which was then BECMG visibility of 10km or more between 6am and 10am. The time period shows that this wasn’t a short temporary condition but a change in the weather (fog, low visibility) which later improved. So in this case, the fog and low visibility over that period should have been cited as BECMG and not as a TEMRO, so that the captain would have been obligated to confront the fact that the airport would not be accessible to him at his time of arrival.

For the actual approach to Lviv, the ATIS information reported fog with a visibility of 150 metres and vertical visibility of 50 metres. The fog and low visibility lasted for an hour and 17 minutes, underscoring the error in citing the deterioration in visibility as TEMRO.

This is why the report emphasises the primary failure of the captain as being willing to depart with a fatigued crew, rather than focusing on his decision to continue despite the weather. In addition, we don’t actually _know _ whether the captain and the crew were aware that they were too low on fuel to divert or whether they were just too tired to think about other options.

Guided by the requirements of national regulations and the airline’s operating manual, the crew and the flight controller failed to take into account the temporary deterioration of visibility and the occurrence of fog at the destination aerodrome.

The report determines that the key turning point is when the crew, in an attempt to maintain their instrument speed, increased the vertical speed of the descent instead of increasing the operating mode of the engines. This is when they began to rapidly fall below the glide path. Following this, the crew extended the flaps and increased the vertical speed again without increasing the engine power, which lost them both indicated speed and flight altitude.

When the radio altimeter triggered to show that they had reached the decision height, the crew did not respond but continued to descend. The indicated speed had dropped to 237 km/h and their flight altitude was 68 metres (223 feet) below the glide path.

Critical to this is the rapid extending of the flaps and what little we know of their reactions, which imply that they thought they were much closer to the runway threshold than they were. Thus, they accepted their distance from the ground as appropriate for the last stage of the flight, rather than focusing on the glideslope which would have told them that they were still some distance from the runway threshold.

The final report cites the following causes

The most probable cause of the accident, collision of a serviceable aircraft with the ground during the landing approach in a dense fog, was the crew’s failure to perform the flight in the instrument conditions due to the probable physical excessive fatigue, which led to an unconscious descent of the aircraft below the glide path and ground impact.

Contributing Factors

Probable exceeding the aircraft takeoff weight during departure from the Vigo Airport, which could result in increase in consumption of the fuel, the remainder of which did not allow to perform the flight to the alternate Boryspil aerodrome.

I mentioned the management culture above, by which I usually mean the attitudes towards safety and following procedure at the operator. But in this case, there’s evidence that a disregard for aviation safety is more widespread than that. Specifically, the fact that after the crash, no one contacted the aviation investigative body about the crash.

The Air Traffic Service was expected to notify the National Bureau of Air Accidents Investigation after declaring the emergency situation. The Rescue teams who were informed of the occurrence of an accident, and the airline/operator of the aircraft, are both expected to report the incident to the bureau within fifteen minutes along with the actions taken. The head of the aerodrome is also expected to report to the bureau within two hours of being notified of the incident.

No one did. The bureau discovered that there had been a fatal crash by seeing it on the news. The airline sent a report of the accident at 08:15 that morning but only after the agency had sent a written request.

You’ll note that although the forecasts were described in detail, there was much less information about the actual weather at Lvlv that morning. This is because the Tower ATC did not report the accident to the Aerodrome Meteorological Station, so the Met Station did not know to take an unscheduled meteorological observation as quickly as possible after the crash. Upon a review of the documentation, it was noted that the Meteorological Station was not on the list of those to receive notice of an emergency.

The report concludes with safety recommendations. The first, addressed to the State Air Traffic Service Enterprise, is simply for the relevant bodies, including the Met Station, to clearly define who should receive an alert in the event of a crash. The recommendations for the State Aviation Administration of Ukraine are focused around cleaning up legal acts and regulations to deal with aviation issues and enforcing those regulations through inspections for compliance.

Those for the operator are particularly depressing, recommending that the operator

- take additional actions to ensure aircraft crew compliance with working hours and rest hours

- develop a procedure for monitoring aircraft loading

- ensure the safety of aircraft on-board documentation

- conduct simulator training with flight crews on performance of landing approach and landing procedure

I can’t help but feel that these recommendations for the operator show just how little is expected of an airline in Ukraine at the moment. In this case, when referring to issues with the management culture, it appears that there is a national and regulatory disregard for aviation safety and procedures to ensure compliance. Every recommendation from the bureau describes something that should already be happening. The need for improvement could be summed up with a single command: Do better.

Worth noting, I guess, is that a heavily overloaded aircraft that’s already going quite slowly is not going to respond well to a sudden pitch-up command, as was noted last week in the flight’s final moments. J.

I don’t think they had even 5 minutes of fuel left in the tank. Incredible.

From the accident report:

This indicates that fuel spilled from the damaged tanks.

That corresponds to 15-20 minutes of flight time – enough for a go-around.

A sad story, and one of very many shortcomings and errors.

The airport authorities have also been severely lacking, but that was more in relation to the handling of procedures after the accident.

The operator must have been one of the worst “cowboy outfits” in the history of aviation. The last paragraphs of Sylvia’s report leave that in no doubt. The recommendations to “improve” the standards are self-evident. So much so that, even in my very first job on a privately owned twin engine Cessna 310 , ALL of the bullet point “recommendations” were adhered to as a matter of course, apart from the fact that we did not have access to a C 310 simulator.

Instead, we were monitored by professional airline captains who were also RLD (Dutch CAA) appointed examiners. In addition, we did regular basic IF training on a Frasca basic IFR simulator that was operated on behalf of a Schiphol-based flying club. It was operated by full-time KLM simulator instructors and examiners. This was all on a voluntary basis.

I flew that aircraft, with another professional pilot and one of the company directors who held a PPL with ME and IF ratings. I logged about 3600 hours on that 310, flying over the whole of Europe, Eastern Europe (still behind the “iron curtain”) and North Africa in all sorts of weather. Because of the discipline imposed by our mentors we did not have one single incident in all those years.

In the ‘eighties Aeroflot operated a flight between Moscow and Havana, Cuba. I believe with IL-62 jet aircraft. The aircraft was not able to make this flight non-stop. Because of the “cold war” and American sanctions, the only airport willing to accept Aeroflot for an intermediate stop was Shannon. They regular oil companies were unwilling to supply jet fuel to Aeroflot, so a Russian tanker had to make regular supplies by sea.

We watched the aircraft take-off on many occasions. It always used a lot of the available runway and did not seem to climb out very quickly either. We – pilots – always had the suspicion that the Ilyushin was quite overweight leaving Shannon. At least, this must have been factored in.

The flights from behind the Iron Curtain would also have stopped at Gander (per Wikipedia and a recent documentary), but even so they would have been pushing their range (2000 miles per W) when flying west (typically into serious headwinds).

What an ill-fated flight, all the way around. And letting airports be run that way?! I wonder if this country black-lists airports with sloppy, illegal management.

Great write-up Sylvia.

PS:

About “tempo” in a TAF: The way we used it was that if it indicated a temporary improvement, we would ignore it. But we were to take it into account if it indicated a deterioration in the weather. We did consider the period of Tempo(rary) deterioration as the actual forecast. Especially if the period covered in the “tempo” would cover the period that included our ETA. In addition, we were to to extend the “tempo” with half an hour before, and half an hour after the ETA.

If I try to put this in simpler terms: If the “Tempo” indicated a temporary improvement, we would assume that there was not going to be an improvement.

If the weather was going to deteriorate during a period which would cover our ETA, we would extend it by a full hour, subtracting half an hour before, and adding half an hour after the “tempo” period.

A couple of items in the report don’t fit together; the damage list describes the underfloor and right outboard fuel tanks as “destroyed” but the writeup says “the fuel tanks had remained relatively intact”, leading to the conclusion that the plane was almost out of fuel. Any idea which is correct? Is there a normal order of use for fuel tanks? (The underfloor tank might have been empty due to being first-used.

I can understand airport staff being more concerned with getting a rescue going after an accident rather than notifying the NBAAI, even if there’s a rule about doing so. OTOH, I wonder whether the airport authorities put the most inexperienced controllers on the third shift, thinking that there would be too little to do to stress them; did the report discuss this?

People who are very fatigued tend to operate on autopilot, falling back on habit and reacting slowly to anything unexpected. In this case, the behaviour of the crew sounds as if they were automatically following the same sequence of actions that they’d taken on previous visits to Lviv, rather than reacting to their actual circumstances at that moment.

I agree. It seems that the crew were fatigued and incapable of thinking logically, The aircraft was probably nearly out of fuel, running on the “fumes”.