Sky Diver Pulled from Aircraft After In-Flight Deployment

On the 1st of August 2024, the École de Parachutisme Sportif de Vannes Bretagne organised a parachute drop for 14. The sky diving centre is a non-profit operating their aircraft under AIR OPS.

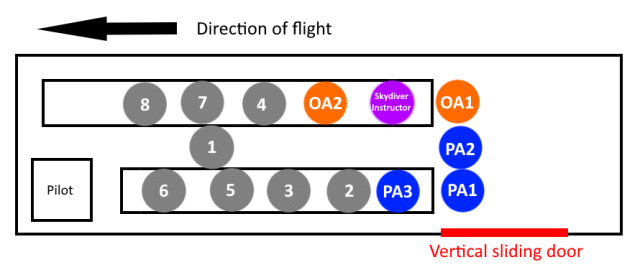

The aircraft was a Cessna 208 Caravan, a single-engine turboprop, registered in France as F-HVPC and owned by the sky diving centre. It was configured for sky diving, with two benches, one of which seats five sky divers and the second seven.

Up to three sky divers can sit on the floor between the benches or by the door, for a maximum of 15 sky divers.

Each parachute system included a harness, a reserve (backup) parachute, the main parachute and an automatic safety device designed to deploy the reserve as needed. The parachutes are connected to their harnesses through risers: webbing straps that group the suspension lines.

When jumping from the aircraft, the sky diver pulls out the handle and releases it, causing the small pilot chute to slip out of a fabric pouch on the back of the harness. The pilot chute catches air which initiates the deployment of the main canopy.

The parachutes had been inspected four months before the jump, 4 April 2024, with the reserve repacked by a certified packer and valid until 4th April 2025.

For the flight that day, there were two jumps planned around 1,200 metres and 4,000 metres. (~4,000 feet and 13,000 feet).

At 1,200 metres, the first jumpers were three experienced sky divers practising precision landing and two students under the supervision of the sky diving instructor. Then at 4,000 metres, the remaining sky divers and the instructor would jump together.

The sky divers carried out their equipment checks on the ground before boarding and would repeat them during the climb before reaching jump altitude. The deployment handles for the main canopy, reserve canopy, and cutaway can easily become dislodged from their housings with minimal movement.

The instructor was responsible for checking the equipment of the two students, which he did. He held C and D licences, allowing him to supervise other sky divers and perform demonstration jumps. He was in training for the federal instructor rating.

The pilot held a commercial licence with 6,600 flight hours, with 5,500 as a sky diving pilot.

It was a hot August day, 28-30°C (82-86°F) and it would have been sweltering in the cabin. They departed Vannes and climbed away, ready for their jumps.

The sky divers were sitting according to their jumps, with the eight sky divers jumping second seated nearest the cockpit, with one on the floor between the benches. The sky diving instructor sat at the end of the longer bench, with one student on the bench to the instructor’s left and one student to the right of the bench, sitting on the floor. The three experienced sky divers practising precision landings were nearest the door, with one on the short bench and two on the floor. The three sky divers on the floor (one student, two precision) sat shoulder to shoulder. Everyone was sitting with their backs to the cockpit.

The aft door was a vertical sliding design of Plexiglas slats. The Cessna 208 was certified to fly with the door open as a part of its sky diver operations. The only restriction was that the door should remain closed during take off and below 500 metres, so that occupants could not fall out at a height too low for the canopy to deploy. The head of the sky diving centre confirmed that it was standard for the sky divers to partially open the door for some fresh air when temperatures were high, in order to cool down the cabin. There had never been any issue with partially opening the door. The pilot had explicitly given permission for this before the flight.

The sky diver sitting on the floor closest to the door had been assigned the task of operating the aircraft’s vertical sliding door. He was very experienced: he held C and D licences and also a federal instructor rating with 3,600 jumps logged. He had attended a briefing before the flight to learn about the door and the precautions to take when operating it. The pilot had told him that he could partially open the door during the climb in order to ventilate the cabin.

It was very hot in the cabin. After checking for any anomalies, the sky diver raised the slats a bit to ventilate the cabin. He opened the door by about ten centimetres (4 inches) to let the air in, slightly less than the height of a soda can.

The instructor, seated at the end of the bench furthest from the door, started to check his students’ parachutes. He started with his student sitting on the floor. The more experienced sky diver sitting next to him on the floor shifted towards the door to give the student some room.

The sky diver sitting by the door positioned his foot to act as a door stop. He felt the sky diver in the middle shift towards the door and press against him. He didn’t move but turned his chest to the right and leaned a bit out of the way.

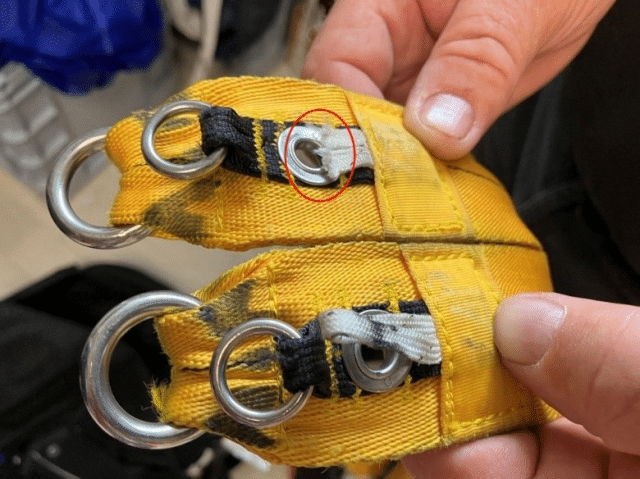

In the process, he must have squashed the leather ball of the pilot chute between the parachute and the floor. What no one realised was that a bit of his pilot chute had come out of the fabric pouch.

The slipstream from the open door caught the chute and yanked it out of the aircraft. This triggered the main container to open, the start of the sequence to deploy the main canopy.

The sky diver sitting on the bench heard something from the door. He turned to look and saw the pilot chute of the sky diver nearest the door fly out of the aircraft. The main canopy container of the parachute was open and being dragged outside. He grabbed the suspension lines but he couldn’t pull the container back in.

The sky diver on the floor was relentlessly pulled towards the door.

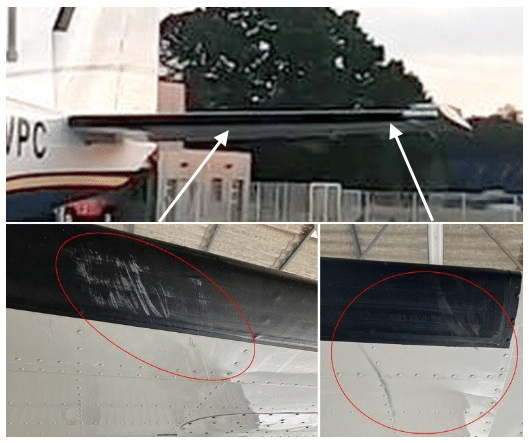

The main parachute opened outside of the aircraft under the left horizontal stabiliser, the small wing on the tail.

While the sky diver was being dragged out of the aircraft, the top loop of the right-hand riser snagged on the door frame and then snapped under the strain. The main canopy was now only partially connected to the harness.

The sky diver felt himself being pulled through the bottom of the door, three slats breaking under the pressure. He felt a sharp pain in his leg as he went over the threshold. He didn’t know it yet but his leg was broken.

The riser that snapped meant that the main canopy was now only partially connected to the harness. The reserve canopy deployed up and towards the tail. It rubbed against the horizontal stabiliser, enough to leave a mark, but thankfully did not get caught up in the tail.

The man sitting on the bench looked out the broken door and saw the sky diver outside of the aircraft under the reserve canopy, with the main canopy still partially connected.

From the sky diver’s point of view, he was suddenly outside of the aircraft. He quickly saw that the reserve had deployed but that the main canopy was still partially connected to the harness. He began to use the reserve canopy to control his descent while keeping the main canopy out of the way so it would not get tangled with the reserve. Meanwhile, the earth was rushing at him.

He hit the ground, hard. He broke his back, fracturing five lumbar vertebrae. All he could do was lie there and wait for someone to find him.

Meanwhile, in the cockpit, the pilot heard a loud noise. They were at about 2,000 feet, halfway to their jump altitude. His stick vibrated strongly. He wasn’t sure what was happening and thought that an elevator may have failed. He pulled back on the power and started to descend. The vibrations stopped but he decided it was better to abort the jump, as he wasn’t sure what was wrong with the aircraft.

The sky divers must have been in shock. The one on the bench said they were already descending by the time he considered saying something, so he presumed the pilot realised what had just happened.

I think it’s fair to assume that everyone was in shock.

They landed safely within a few minutes. The pilot had no idea that he had lost a passenger until he had taxied to the parking stand. He immediately called ATC to say they needed an emergency search for the sky diver.

There are no details about the search and rescue other than that the pilot told the BEA that the sky diver was “quickly found” by the rescue services.

In fact, in general, I’m disappointed by the detail in the BEA report. There are a number of angles that seem not to have been explored at all. That said, I like that the report is careful not to assign blame or second-guess anyone’s decisions. Cracking open the door to get some air into the hot cabin was authorised and the sky diver assigned to the door was experienced and properly briefed. All of the equipment checks were completed as expected.

The key here is the positioning of the sky diver. This meant that the leather pilot chute ball was almost certainly squished between the parachute and the floor. Many sky divers prefer the leather ball: it’s easier to grip and doesn’t break as easily as a plastic ball. But the leather also slides less easily, which explains why it got trapped, pulling out the pilot chute.

Further, the pilot chute pouch, on the right side of the back, was directly exposed to the slipstream. It was a sequence of events that no one had considered.

When the right riser snagged on the door frame, the textile loop securing it severed, triggering the reserve deployment, exactly as designed. It was pure luck that neither canopy caught on the horizontal stabiliser. The sky diver managed both canopies to the ground, which speaks to his experience level.

The report concludes that although the risk of a parachute snagging on the horizontal stabiliser or elevator is a known hazard of sky diving, no one had thought through the interaction of the airflow from the partially open door.

As a result of this incident, the sky diving centre no longer allows for the door to be opened during flight, not even partially, except during the drop phases.

It must get awfully hot in the cabin but that’s still better than suddenly finding out you are outside of it.

During our recent holiday I used the opportunity to take a flight on a powered paraglider. With an experienced pilot of course. Not nearly as exciting as a real para jump, the pilot and passenger sit in a cage with an engine om the back of them. I sat in front; there was not much between me and mother earth a few hundred feet below. The whole thing is kept aloft on a parasail, in other words a parachute. At least, during take-off it is already brought up steady, forming a wing by the airflow as it accelerates before leaving the ground. We were up for 40 minutes, a great experience. Excitement enough for an 82 years old, still recovering from a triple bypass operation.

Given a chance, I would do it again !.

But skydiving is quite another thing. The decision to leave a perfectly good aircraft when it still is in the air goes against the instincts of a pilot, I guess. And of course the decision to actually leave the safety of the aircraft is not for everyone.

Having said that, it is obvious that these skydivers did everything according to the book. And it is evident that the pilot did a great job too.

It was just an unfortunate set of circumstances. A freak occurrence.

Fortunately the skydiver who was pulled out survived.

I wish him a full and speedy recovery.

Wow! I hope you get the chance to do it again. It sounds great.

It has been over 30 years since I was a skydiver, and I never got even to an A rating — a case of Life intervened — so the below should be taken with a grain of salt.

Having the door at all during flight certainly seems wrong to me; I recall the person who opened the door to drop a test streamer (at ~2500 feet) shouting “Door!” before they moved. ISTM that leaving it open while taxiing, and closing it before going onto the active, might be reasonable in hot weather, but someone would have to be responsible for closing.

My experience after I graduated from ripcords was limited to a pilot chute packed in a pocket in one of the thigh straps of the harness. I remember some people preferring the pilot pocketed under the main, but not why; when I try to fake the pull-out motion it doesn’t seem easier from that position. ISTM that there’s a significant safety advantage in the thigh-strap pocket because the jumper is much more likely to see whether the drogue is starting to come out of its pocket. (IIRC the pocket itself is also tighter.)

I’m a bit surprised that the experienced parachutist didn’t cut away the main to make the reserve more controllable; this should have been possible given the altitude and might have made the landing easier. (When I was working on my A rating, one of the tests was to hang in a harness while a series of flashcards were shown overhead; the object was to make the correct reaction reflex rather than thought. Some were riser twists that could be undone, but several called for pulling the cutaway handle and then the reserve handle.) The pain of the broken leg may have complicated this.

I wondered about that but I think it comes down to startle effect and lack of altitude. They didn’t get into it at all in the report (I even checked the French) but I wondered also if he might have hoped that the main parachute would help to slow him down? I know next to nothing about skydiving though. Maybe one day…

I never went down under a reserve, but my understanding was that a fully-inflated reserve would slow the fall just as much as a main — especially since many newer rigs had two identical canopies, instead of a square main and a round reserve. The lines on both canopies are similar length, so having two canopies out would leave both tangled or underinflated; it’s possible the jumper thought that the reserve wouldn’t fully inflate soon enough if the main were cut away, but I wouldn’t expect that if the reserve were already partially open. A jumper with that many dives should have some experience with getting rid of a bad main — ISTR being told that the main fouls about 0.1% of the time (seriously fouls — I had to deal with two riser twists in ~40 jumps, but those aren’t hard to fix) — but there may have been too many things going wrong for reflexes to be reliable.

Having recently watched footage of a parachutist deploying the reserve with the main not fully inflated, the half-inflated main can slow the descent quite a bit and make the reserve slow to unfold. Cutting away the main in that situation accelerates the fall, but at low altitude, that’s probably not wise.

Sylvia reports that the pilot noticed a problem at 2000 feet; when I was a student, that was standard opening altitude for a C license. (A D license could wait to 1800 feet.) Cutting away immediately should have provided a better chance of a controlled landing — modern canopies open very quickly, and can be landed very gently even if they’re falling a bit faster than the standard (~1000 feet/minute) — but it would depend on exactly how entangled the two canopies were; a clear reserve should allow for a gentle landing, but a full cutaway might not have gotten the reserve clear of the main. This also depends on the nature of the reserve canopy; 32 years ago matching main and reserve were strongly encouraged, but I heard of some people jumping a square main with a round reserve, probably because the rounds were cheaper and having to cope with their harder landing was so unlikely.

I only ever did one jump: it was free, courtesy of the RNZAF. Into the water off Hobsonville, from a Dakota at 800 feet. We were briefed that if the main chute didn’t deploy, we had a maximum of two seconds to release the reserve. We wore life jackets, but were told not to inflate them so they could be passed on without re-packing and replacing cartridges.

We jumped in pairs, to make sure we landed in the fairly narrow strip of water. The No 1 jumper before me was unused to flight and ‘starfished’ in the door, jamming hands and feet into the corners. The Jumpmaster handled it well, patting him on the shoulder to reassure him and easing him back into the aircraft. As soon as he had released his grip, the Jumpmaster pushed him out. We could hear him scream for some distance behind the Dak.

It was then too late for me to jump, so I waited in the doorway for a full circuit. I was used to looking down from height, so no problem. We flew directly over my house not long before the jump, and I wondered if my wife was watching. Not likely, as I hadn’t mentioned my jump.

When I went I could feel the main chute unravelling from its pack, so no need for the reserve. We were using loop harnesses and had to release the cross-lock and ease into the bottom loop, so had to release the reserve first. That pack was secured by a long length of cord, with a knot I’d tied. Which didn’t hold. If I close my eyes, I can still see the pack tumbling over and over till it splashed. As briefed, I put my arms straight up about eight feet above the water so that the chute wouldn’t cover me, and made my own splash. The rescue boat went off to find my reserve pack before collecting me – packs are scarcer than Flying Officers.

Strange how some memories will last clearly after 53 years.

David