Pushing Limits: The Fatal Crash of a Newly Qualified Pilot

On the 11th of October 2020, a Cessna FRA150L Aerobat departing from a grass field in the Lake District crashed shortly after take-off. The pilot was killed in the impact. Yesterday, the UK Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) released the results of their investigation.

This accident is tragic, in that it is a story of a low-hours pilot who killed himself through overconfidence. But it is also interesting for the view it gives us into the culture of general aviation in England.

The pilot had purchased the Cessna FRA150L Aerobat in June 2019 while he was part way through training for his Private Pilot’s Licence (PPL) and used it for the remainder of his training. His primary instructor described him as a “good solid average pilot” although he also said that the pilot could be a bit hit and miss at times and was “not the most consistent student”. He said that the pilot was one of the more aggressive, pushy students, leading the instructor to have to “reel him in” and explain what was acceptable and what was not. At times, he said, he had to be quite firm with him.

One example of this was that the pilot had a habit of not wearing his shoulder straps. The instructor said the pilot was reluctant to put them on and that the instructor ended up telling him that he would not fly with the pilot unless he wore them.

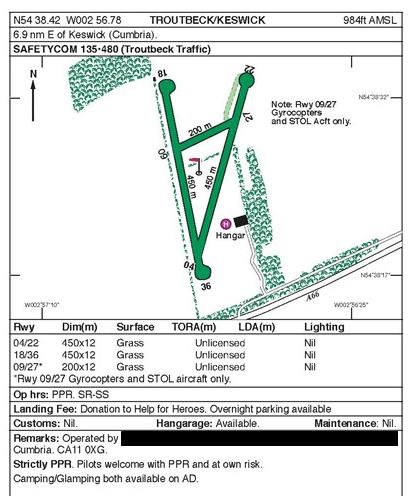

On the 25th of May, the instructor authorised the pilot’s cross-country flight, a milestone when training for the PPL, as the student must set up a route and navigate solo. The instructor must check the airfields, the route and the weather to ensure that the pilot’s skills are up to it. The pilot chose to fly to Troutbeck Airfield, a private airfield in the Lake District with multiple grass runways. The airfield is listed as PPR (Prior Permission Required); the owner asks pilots to contact the airfield the day before arrival so that he can make sure that the pilots have the airfield’s plates and that they have experience with short airstrips. He also ensures that the planes are “low energy aircraft”: microlights or aircraft capable of short take-off and landings, such as the M7 or Piper Super Cub. The owner then asks the pilots to call again before takeoff so that he can advise them of the current weather conditions and wind direction and let them know which runway to use. If he has any doubt about the aircraft type or the pilot’s experience, he will not permit them to visit.

On the occasion of the pilot’s cross country flight, he had arranged to fly in with his friend who would by flying a Piper Super Cub that day. The other more experienced pilot contacted the airfield owner for PPR and added that he would be bringing a friend. However, he did not mention the aircraft type or that the friend was a student pilot on his first solo cross country flight. As the airfield owner had known the more experienced pilot for some time, he presumed that anyone coming with him would be in a suitable aircraft for a short grass strip.

The instructor approved the flight, feeling that the pilot’s attitude had improved and that he was progressing well through the course. It is the training organisations responsibility to check that the aerodrome is suitable. If the pilot has chosen to land at an unlicensed airfield, the training organisation is responsible for assessing the suitability. This clearly did not happen.

This 40-second video is of another pilot flying into runway 3 at Troutbeck Airfield. This is unrelated to the crash, just an opportunity to show the location.

When flying to an airfield, basic performance calculations are needed because of variable factors which affect the performance, such as the elevation of the airfield, the weight of the aircraft and the temperature that day. If you are flying to an airport with a runway in excess of 1,000 metres, such as the pilot’s base, these factors are unlikely to affect your small plane’s ability to take off and land. However, short-field airports with runways under 500 metres are another situation altogether. A grass runway needs 20% more take-off distance than a hard runway and, if that grass is wet, it’s 30%. When several factors affect the take-off distance, they must be multiplied which means that the take-off distance can quickly become surprisingly high. When dealing with short-field runways, it is critical to ensure that the take-off distance required, including an additional safety factor, does not exceed the take-off run available.

This is why the owner wanted to talk to the pilots before they flew in: Troutbeck had two grass runways of 450 metres at an elevation of 984 feet. Runway 36 has a gradient of about 3.3% from the threshold to the intersection with runway 4, after which it has a negative gradient, that is to say, the runway has a slight hump and the elevation of both ends of the runway is about the same.

The instructor did not contact the airfield and did not ask to see the pilot’s performance calculations. He reminded the pilot to obtain PPR but didn’t check that this had been done.

The two pilots arrived at the airfield, one in the Super Cub and one in the C150, without incident. However, the owner was shocked to discover that the pilot of the Aerobat was still a student. He said that if the more experienced pilot had mentioned this when phoning, the owner would “most certainly have not allowed him to land.” The owner said that the lack of experience and the poor ground conditions at the time meant that he would not have given the C150 pilot permission to visit the airfield.

The pilot completed his PPL in July 2020 and the CAA issued the licence on the 27th of August. However, a few weeks before the licence was issued, he decided he wished to fly his C150 to his friend’s private grass airstrip. The airstrip has about 330 metres of Take Off Run Available (TORA) with trees and residential houses in the undershoot and overshoot. This would be considered a challenging airfield even for an experienced pilot but on this day, the pilot was officially still a student.

When a pilot has passed his licence skills test but not yet received his licence from the CAA, all solo flights must be supervised by a flight school. The pilot sent a text message to his supervising instructor, who had flown with the pilot at the beginning of his PPL but not since, about the flight. Somehow, the instructor got the impression that the pilot was going there as a passenger in the friend’s M7. He responded, “Go for it.”

While the pilot was preparing for take-off, the instructor overheard him on the radio and realised that the pilot was planning to fly the C150 to the private strip. The instructor knew the airstrip and that it was not suitable for a C150. He tried to phone the pilot to stop him but received no reply. The instructor jumped into his car and drove to the airstrip, which was about 45 minutes drive away, arriving just before the pilot landed.

The instructor made it clear that he had driven all this way because he was completely dismayed that the pilot had flown into this airstrip. He explained that the airstrip wasn’t suitable for a C150 regardless of the experience of the pilot but now that he was here, someone else should fly the C150 home. He also spoke to the pilot’s friend about the issue.

The pilot disregarded the instructor’s advice and flew the C150 out of the airfield.

A few days later, the instructor spoke to the pilot again to explain about performance issues and the hazards of flying into short-field airstrips. He gave the pilot advice as to the kind of flying that could help him to gain experience along with a number of airfields, none of which were grass or “performance limiting” airfields (runways where the take-off performance calculation may show that the runway unsuitable for the aircraft’s requirements).

On the 11th of October, the pilot and his friend agreed to visit Troutbeck Airfield again, this time carrying a passenger.

At this point, the pilot had a total of 69 hours, 52 on type, and three hours flight time in the past 90 days.

This time, the friend would be flying his Maule M7: a single-engine tail-dragger popular for its versatility as a STOL aircraft (short take-off and landing). They arranged to meet at Netherthorpe, the friend’s home airport, and then fly together to Troutbeck.

A third pilot, based in Auchinleck (near Prestwick) contacted the owner of Troutbeck Airfield, saying that he was coming to visit in an M7 and that another M7 pilot was also coming. He did not mention any other visitors to Troutbeck.

The airfield owner was concerned about the inbound M7 as there were some wet areas at the airfield that he felt that the pilot needed to be aware of being taxiing off the runway; however, he assumed that the other M7 pilot was already airborne and couldn’t be reached. He did not know that the C150 pilot was also planning to fly in. The runway was wet and the owner felt that the conditions were not suitable for a C150.

Starting at his home base, the pilot topped up his fuel, requesting that the fuel tanks “were brimmed”, that is, as full as possible. The weather was good with scattered cloud and the wind was coming from the north at about ten knots, which meant that runway 36 would be in use with about a ten knot headwind. He messaged his friend to ask whether the Troutbeck owner would require a call in advance. The friend responded: “CALL PROBABLY GOOD BUT NOT ESSENTIAL”.

The pilot and his passenger flew to Netherthorpe to meet the pilot’s friend. Netherthorpe also required PPR, that is, he should have rung in advance to ask permission to fly in, however he did not. The C150 landed on the grass runway 36 without incident.

His friend arrived in his M7 about ten minutes later. He was a member of the resident flying club and had an aircraft based there, so he did not require PPR. He knew that the C150 pilot had flown to Netherthorpe on a number of occasions and it didn’t occur to him to remind the pilot that he needed PPR, he just assumed the pilot would phone first.

The two aircraft departed the airfield for Cumbria, with the more experienced pilot taking off first. The C150 pilot executed a short-field take-off, applying full engine power prior to releasing the brakes and FLAPS 10 selected, and managed to take off in just 200 metres.

Based on the conditions and the weight of the aircraft, which we’ll get back to later, the pilot should have allowed for 430 metres of available runway for take off, including the safety factor. Without the safety factor, the aircraft needed 301 metres, which means that he took off early and likely slow.

The runway that day at Netherthorpe had 361 metres of available runway.

The pilot of the M7 knew that the Auchinleck pilot had spoken to the owner of Troutbeck so he did not feel that he needed to phone for PPR. The M7 is quite a bit faster in the cruise and so the M7 pilot arrived about 15 minutes before the C150. He transmitted on the microlight airfield frequency as he approached Troutbeck and during landing on runway 36. After he landed, he attempted to call the pilot of the C150 to warn him that the runway was “sludgy”. Later, he couldn’t remember if he got through to the pilot or not.

The M7 pilot was talking to the airfield owner outside of the hangar when the C150 came into view. The owner originally thought it was an Aviat Husky (a two-seater plane capable of very short takeoff and landing) or maybe another M7; however when the aircraft was overhead, he saw that it was a C150, which he didn’t want coming into his airfield with the runway wet. He ran into the hangar to get his hand-held transceiver and made repeated calls to attempt to speak to the pilot but received no response.

The C150 continued his approach and landed on runway 36. The owner was furious that neither pilot had bothered with the PPR, although he understood that the M7 pilot believed that he had “PPR by proxy” from the Auchinleck pilot who had called that morning. However, the owner was quite clear that no one had said anything about a C150 coming to the airfield and that it was not appropriate for a C150 to fly in and out of the airfield under the current conditions.

After the C150 vacated the runway, the M7 pilot waved his hands to try to show the C150 where to park to avoid the boggy ground. The pilot misunderstood and taxied near the hangar, parking the C150 in the mud. After he’d shut down the aircraft, the M7 pilot came over to speak to him before he and his passenger went to the hangar.

The C150 pilot told his friend that the flight from Netherthorpe had been very stressful, although he didn’t explain in what way. The passenger later said that radio had been intermittent because the pilot kept having to climb and descend to avoid clouds while he was trying to keep up with the M7. The M7 pilot explained that the airfield owner was upset that he hadn’t requested PPR and that the runway condition wasn’t suitable for a C150. He said that he should take the passenger back in his M7, or maybe he’d take all three of them and leave the C150 there to be picked up once the area dried out. The pilot turned him down, saying, “No, no, we’ll get out easily.”

The pilot and his passenger then spoke to the airfield owner, who repeated that the C150 should not have landed at Troutbeck under these conditions. The pilot apologised, saying that he thought someone had phoned on his behalf to ask for PPR.

The owner told the pilot that he should take the C150 out solo to keep the weight down and the passenger should travel in the M7. He then explained to the pilot that he needed to use the full length of the runway to ensure he had the full takeoff distance available to him. From the intersection, the runway is about 320 metres long but the full runway available, if you backtrack to the threshold, is 450 metres. The owner explained that the pilot would need to backtrack from the intersection of runway four to the runway threshold to start the takeoff roll in order to have enough runway available to him for take off.

The pilot agreed.

The owner then spoke to the M7 pilot again, telling him to make sure that he took the passenger back in the M7 and that the C150 used the full length of the runway.

The two pilots walked to the runway talking about the owner’s instructions. However as the runway was wet and there is a slight incline on the first half, the pilot decided tha he would rather backtrack about halfway from the intersection to the threshold of runway 36 and start the take-off roll from there. The M7 pilot did not argue.

Back at the C150, the pilot discovered that his aircraft had sunk into the boggy ground and he was unable to taxi clear.

His friend leant on the tail to take the weight off the nosewheel and then pushed the aircraft forward out of the mud. Once clear, the pilot taxied along runway 22 and then as he reached the intersection to Runway 36, he turned right onto the runway (rather than left to backtrack) and accelerated the engine to full power before starting the takeoff roll.

The C150 quickly became airborne and then drifted to the left as the pitch angle increased. The pilot then appeared to start a left turn. The left wing dropped and the aircraft entered a “near vertical dive” from 50 feet above the ground, crashing into a field next to the airport. The aircraft landed on its nose.

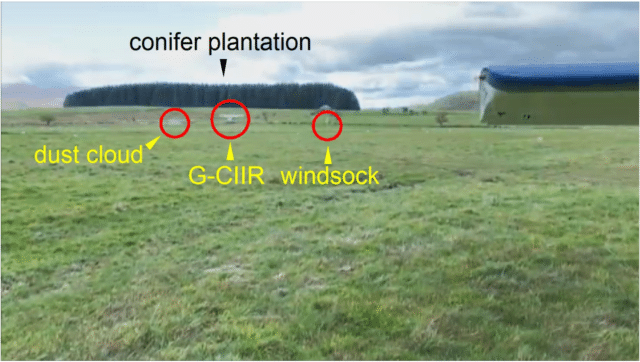

The friend took a video of the take-off on his mobile phone. This has not been released but the final report includes stills from the video and a full description:

As the video footage of the takeoff started, a light-coloured dust-like cloud could be seen near to the runway behind G-CIIR (Figure 5), which then rapidly dissipated.

The dust-like cloud wasn’t from the aircraft but likely from the runway soakaway as the aircraft travelled over it. There was no evidence of anything wrong with the aircraft before the impact.

Very shortly afterwards, G-CIIR lifted off at which point the aircraft yawed to the left whilst also briefly banking to the left (Figure 6), before the wings then levelled. The aircraft’s track over the ground was estimated to be approximately 20° to the left of the extended centreline of the runway, which placed the aircraft on a course towards the conifer plantation.

The AAIB conducted test flights which showed that in full power stall, the aircraft would yaw left and then roll left unless rudder was applied to counteract this. This explains the initial veering to the left.

I initially thought that the increase in pitch was likely to be the pilot pulling back as an instinctive reaction to the conifer plantation; however the AAIB flight tests showed that this pitching up was probably because the elevator trim was still set for landing. If the pilot relaxed the pressure on the control column, the nose would pitch up and the airspeed decrease.

During the next few seconds, the aircraft was observed to climb gradually whilst maintaining a predominantly wings level attitude heading towards the conifer plantation, but as it reached a height of about 50 ft agl, the aircraft proceeded to roll quickly to the left whilst also starting to pitch nose-down whilst descending (Figure 7). The final image of the aircraft (Figure 8), captured less than two seconds later, showed the aircraft’s nose was 20° below the horizon and the bank angle had reached nearly 90°. A sound consistent with the aircraft striking the ground was recorded 1.6 seconds later, which coincided with the sound of the engine stopping. The estimated elapsed time from the aircraft becoming airborne to it striking the ground was just over 10 seconds.

Quite frankly, it would take one hell of a pilot to recover from a full-power stall at 50 feet above the ground.

The friend and the passenger saw the C150 enter the dive and rang emergency services before running to the plane. The found the pilot unconscious, hanging by his lap straps. The pilot did not appear to have put on his shoulder straps and the injuries to his head and chest were consistent with this. The first responders could smell fuel and saw it pouring from the right wing as well as smoke from the fire. Another witness came to help and three of them pulled the pilot out as the aircraft toppled over onto its back. They placed him on the (upside-down) wing and tried to give the pilot first aid, following the instructions of the emergency services on the phone.

Various rescue and fire-fighting services arrived some ten to fifteen minutes later and attempted to help the pilot. By the time the air ambulance arrived, just a few minutes later, the pilot was dead.

They found the pilot’s checklist in the mud, open at a page marked as AFTER START, TAXYING and POWER. The pre-take off checks were on the following page which was clean. The friend with the M7 said that based on the time from taxi to take off, he did not believe that the pilot could have completed power or pre-take off checks.

The medical examination concluded that it is possible that the pilot became incapacitated in the final seconds of the flight; even though there is no evidence to suggest this, it could equally not be excluded.

The investigators estimated the take-off and landing weights of the C150 based on the fuel consumption. Fully fuelled before departure, the C150 with the pilot and passenger and baggage weighed 1,686 at take off. Based on the fuel remaining in the tanks, the aircraft’s take off weight at Netherthorpe was 1,678 pounds. Taking off from Troutbeck without the passenger, the take-off weight was calculated to be 1,480 and the centre of gravity of the accident flight just aft of the permitted range.

The C150 Aerobat maximum authorised weight is 1,650 pounds (750 kilos).

Based on the video footage taken by his friend on his phone, the C150 lifted off with a take-off roll of about 230 metres.

The investigators did the performance calculations that the pilot should have done in the first place, taking into account the atmospheric pressures and state of the runway.

At Netherthorpe, the landing distance required and the take-off distance required for the C150 for the conditions of the day were beyond the runway distance available with the additional safety factor required. The pilot was able to land and take-off but he was pushing limits for the performance of the aircraft and there was no margin left for error.

At Troutbeck, with only the pilot and baggage on board, the take-off distance required for the C150 after based on starting from the threshold was 439 metres; with additional safety factor it was 584 metres. The take-off run available is 450 metres.

However, the pilot started from the intersection, avoiding the upwards slope. This reduced his take-off distance required to 428 metres with no safety factor. This eleven metres saving by avoiding the incline was offset by the take-off run available, which was now only 320 metres.

The pilot had flown only two hours since passing his licence skills test in August. If he had prepared more thoroughly, he would have seen, or even remembered, that Troutbeck Airfield was “Strictly PPR”; if he had made the required call, the owner would have refused him. Even after that, if he had only heard the transmissions from the owner on approach, he would have been refused permission to land; he had plenty of fuel to divert to a more suitable airfield.

With no PPR, in an aircraft that was over the maximum weight for all of the flights until the passenger was left behind and a flight plan which took him to runways shorter than required for safe take-offs and landings, it seems that the pilot had either forgotten to calculate the performance and weight and balance figures or he assumed that he didn’t need to, as he’d been to both airfields before. He wasn’t aware or didn’t think it mattered that his previous trips were without a passenger and in better conditions. The fact that his previous visits to short-field runways had ended up with him being chastised did not appear to dim his enthusiasm.

It is almost certain that he did not perform his engine power checks or pre-take-off checks. The AAIB are much more patient than I am; they theorised why he may have failed to do so.

This may have been because the pilot did not want to get his aircraft stuck in the mud, as had happened after he initially tried to start taxiing. This may also be the reason why he started the takeoff run from the intersection rather than backtracking to the beginning of the runway, as instructed to do by the airfield owner, or to a point halfway between the intersection and runway threshold, as he had told the M7 pilot he would do.

The point remains that the pilot appeared to consistently disregard advice from his instructors and the owner of the airfield, all of whom had much more experience than he did. As the report puts it, the chastisement with his instructor in the weeks after his final skills test was disregarded. To top it all off, he ignored the advice from the airfield owner and rushed to depart Troutbeck, without using the full runway and seemingly without reconfiguring the aircraft for take-off as he did not take the time to complete the pre-take-off checks.

Finally, the impact forces on the pilot were estimated to be between 3 and 4.25 g as the aircraft crashed into the waterlogged ground. This isn’t particularly high and could have been survivable. It was the head and chest injuries which killed him and those could possibly have been reduced through the use of a shoulder harness.

The report concludes that there were a number of shortcomings with the preparation for the flight that contributed to the accident.

In addition, opportunities were missed to prevent the accident because the pilot did not heed the advice not to operate into grass, performance-limiting airfields, did not obtain PPR and was probably not on the correct radio frequency on arrival. It is likely that the pilot did not fasten his shoulder harness, against the strong advice of his instructor, and this action may have meant the accident became unsurvivable.

The pilot’s friends and family were devastated by the loss, describing the man as an inspiration with an appetite for life. Enthusiasm and the willingness to jump at opportunities and push personal limits can be fine traits in a man on the ground but as this accident shows, flight is unforgiving. The checklists and requirements for planning are not pointless paperwork; they are critical to the safe operation of the aircraft. This accident was tragic and completely avoidable, if only the pilot had respected the complex nature of aviation.

I read the accident report too, and the whole thing just makes me sad. Such a needless, preventable tragedy. When I was learning to ride motorcycles, my instructor talked about the margin of safety in terms of “a dollar“, where every choice you made took some number of cents away from the dollar, and the trick was to make sure you didn’t spend your whole 100 cents so you could still deal with the unexpected when it arose. If this pilot had been a little more cautious about not eroding his safety margins, he might still be alive.

As you say, flying (along with many other activities) is a margins game – the more you cut the margins, the less room for error or the unexpected, and the higher the demands on the pilot. At some point the margin can become negative, and then you’re frankly doomed.

Sad the pilot didn’t get the chance to learn this lesson in a non-fatal fashion.

I’d say “the pilot didn’t take the chance to learn this lesson in a non-fatal fashion.”

Not trying to be harsh, but the guy had plenty of opportunities before the last one.

I wonder what is auto driving record was like. And I wonder how long he would have lived if he had done deep water scuba diving. The only good news in this story is that he didn’t take anyone else with him.

There are many excellent civilian trained pilots however this reinforces my concern about the civilian training criteria.

I am afraid it all comes down to money. This pilot would have never survived a Military Flight School’s program. He would have been washed out the first time he failed to latch on his shoulder harness.

If the flight school had been more concerned about teaching pilots to fly than making money, they would had sent this guy packing long before his first solo.

Flying is not for everybody and everybody who wants to fly and has the money to do so, is not capable of flight.

But as they say, Money Flies, BS walks. John Denver would still be alive and flying if he had been taught to “Fly the Plane”.

Toxicology showed that the pilot, described as “inspiration with an appetite for life”m also took cocaine, although he was not intoxicated during the accident flight.

He may have had a tendency to make bad choices?

I left that out as it was not seen to have affected his judgement for the flight but it did give me pause.

The crash pilot with three whole hours (3!) in last 90 days clearly cut lots of corners but the “friend” did too. The friend was an experienced pilot who directly witnessed the crash pilot being repeatedly chastised by the airstrip owner and the instructor yet kept enabling inappropriate behavior. The friend knew the owner would not approve of the C150 on his airstrip even with better ground conditions and a skilled pilot, yet he didn’t even have the crash pilot call ahead.

I pity the poor instructor and the owner, both of whom worked very hard to do the right thing. And of course they would be the ones sued if there was a lawsuit.

How do you instructors keep your stress and blood pressure under control??

Igeaux has the best comment so far. I wholeheartedly agree with his (or her?) assessment that suggests that the flying school where this pilot had been trained was severely lacking in oversight.

A cocky, overconfident and not very experienced young man (who may, or may not have been under the influence of narcotics taken earlier, as Mendel suggests), a pilot who does not take advice from anyone, not even putting on his shoulder harness, is a “dead ringer” for an accident. Which, sadly, was fatal in this case.

The instructor should have been firmer too. But yes, it is a known fact that this is hard to keep up if the training establishment itself does not really maintain high standards of discipline.

Who am I to comment? I have done stupid things myself. I have embarked on a solo cross-country flight as a student pilot, without even informing my instructor that I was going out in marginal weather, over the bush of Africa, with few landmarks and even with charts that lacked terrain features in all the chart segments of my intended flight.

I have completed banner-towing flights under weather conditions that in one particular case closed a large airport like Frankfurt am Main (EDDF) to all traffic.

At least, I hope that I can say that I took the lessons to heart before I had to learn, or re-learn them the hard way.

You do make a good point, he should have been more cautious, I wish he was. But after 50 or so hours of simulating the flight, and a cardiologist assessment pointing towards a heart attack causing lack of pilot input, the best hypothesis is that the crash was caused by lack of pilot input post take off due to unconsciousness. While extra caution may have increased survivability, there’s still no guarantee.

It’s not right to speak ill of the dead, and frankly, this is the first time I’ve seen such insult to a good person cut down in their prime. He was my father, and I miss him every day.

I am sorry for your loss.

The job of a flight school is to teach knowledge and attitude, but it’s limited. Flight schools generally don’t teach full flaps full power stall on go-around procedures. And if the instructor is “quite firm” with the student for their attitude, the student may dissemble and show a better attitude for a few lessons (to get their solo flight authorized) without a corresponding growth in insight. What we can say is that the pilot would have known how to safely fly the aircraft, which is the job of the school. He simply chose not to do it.

On his previous departure at Netherthorpe, the pilot managed to take off with 200m takeoff roll in dry conditions. It appears there’s actually a soft field takeoff technique that involves getting airborne as soon as possible and then picking up more speed flying low over the runway in ground effect.

But that wouldn’t have worked on the accident flight because the mud had slowed the right main gear wheel down; the pilot applied left rudder to counteract the drag, but was slow to center the rudder when the aircraft lifted off. An experienced pilot would have been “ahead of the plane” and expected it. This pilot was not, and that’s why the aircraft veered left at liftoff, heading towards the trees. If the pilot had veered off like that at the end of the runway, he probably would’ve crashed into the trees directly.

The pilot now found himself low, slow, and headed towards some trees, with the aircraft trimmed nose up. An experienced pilot knows there’s not enough energy to clear the trees, pushes the nose down to pick up some more speed, and then “hops” over the copse. The beginner pulls the aircraft up immediately and stalls.

I don’t expect either procedure is taught at flight schools for the PPL: neither the takeoff with asymmetric drag, nor the full power stall with the aircraft trimmed for landing. The pilot had confidently put himself in a position that exceeded his abilities, and threw all warnings to the wind. He might’ve pulled it off if he had not veered left at liftoff, but with no margin for error, the mud on the wheel did him in.

I find it hard to imagine what the flight school should have done differently.

I see the point Mendel is making. Yet, in my opinion one of the duties of a good flight instructor is to make an assessment of elements that affect the decision making of the student. Meaning: recognising problems that point to a lack of discipline and refusal or unwillingness to take good advice on board. When I reported back from my cross-country flight I got a very stern lecture, I was grounded for two weeks and the instructor took m e through the scenario with a step-by-step analysis of my “sins”, the reasons and the potential outcome if things had gone wrong.

He also went through the things that I had done right, it was a very comprehensive post-flight briefing from which I learned a lot.

This instructor was an active commercial pilot and had many examples of situations that had been preventable, but ended badly,

My solo cross-country flight was an example of overconfidence. My instructor (Colin Horsfall) turned it into a lesson that stuck. Even if it did not entirely stop me from doing things that, looking back, were stupid.

Igeaux says ” This pilot would have never survived a Military Flight School’s program. He would have been washed out the first time he failed to latch on his shoulder harness.” In what country? When a group of us went to see Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the US Air Force officer (ROTC, MIT electronics) said the zooming lights were obviously fighter pilots (she used a ruder word); she was justified, because that was around the time a couple of Dartmouth pilots had been grounded for slaloming up a line of chairlift towers — but they weren’t canned because the program would have been understrength and so shut down. I suspect instructors in the military vary just like other human beings; some are lax, some jump hard on every offense, and some make mistakes a learning experience (as Rudy relates).

” In what country?

USMC at NAS Pensacola. By 1968 the military needed pilots, at this point in time not many young Americans wanted to go to Vietnam. The Military still did not want poorly trained pilots.

Before entering the Marine Corps, I had about 400 hours, learned to fly from grizzly old men who had flown in WWII. They were not easy on me and I thought I knew how how to fly. Lucky for me, I took uncle Chuck’s advice and keep my mouth shut did, not mention my Civilian license nor even take it with me. {Uncle Chuck flew P51s with the 8th Air Force, during WWII, Rotor-wings for the Army in Korea and Vietnam and had Australian Helicopter license #2. He lived to tell the stories so I listened to him.

A couple other flight students also had civilian license and talked about, “already being able to fly.” The instructors threw so much at them they could not keep up with the program and were sent off to the Surface Navy.

At least 25% of every group of flight cadets washed out of AOCS. We usually lost a few more when we went to the T2 up a NAS Meridian.

Like Rudy, I have pulled some stupid stunts, I once flew a loop around a Mississippi River Bridge and I’ve rolled a Beach Bonanza, thanks to good training, I have to managed to live to 73 and logged well north of 8,000 hours. Since leaving the USMC, I have not been paid for a single hour of flying. I love flying old and or slow airplanes. Most of my recent time has been in Harry’s Stearman or Paul’s Carbon Cub.

Someone above mentioned Motorcycles, they are my other love, have been riding for 60 years. I still go to a Motorcycle Performance school a week or so every year. Look for the hardest instructor I can find and tell them, make me earn it.

My name is pronounced “eye-Go” not Ego, it is best to be humble with things that can kill you.

Damn, what is it about pilots in their 70s. They are all hard as nails :D

I wonder if, given the accident pilot’s rosy view of his own skill set, he considered the short takeoffs to be an achievement instead of a mistake in taking off slow. At Netherthorpe he was estimated to lift off at 200m at 63 KIAS. On the accident flight he took off after 230m (did not see an estimate of takeoff speed in the report ) with TODR at 429m without a safety margin.

“Hey, look at my mad skills!”

Yep. It’s not a skill, it’s physics. Anyone can lift off quite early, but nobody can climb that early. With a bit more experience, he’d have figured it out – or with a bit more attention in flight school.

I believe this accident illustrates why airline passengers are supposed to adopt the “brace” position when a crash is imminent: survival is so much easier if you don’t start with a head wound.

I can figure out what the “airfield’s plates” are as you’ve included an example figure, but it’s not explained when first mentioned in the body.

Ah, fair point, thank you. I try to explain jargon as I go but sometimes I miss it.