Pave Hawk Helicopter and Crew Destroyed by Bird Strike

It was a quiet winter evening in the English village of Cley next the Sea, population 400. 2014 was just one week old and everyone was just getting back into the swing of post-Christmas living. Peaceful. Quiet. Until a flock of geese took down a US Air Force helicopter in their backyard.

The helicopter was part of a two-aircraft formation on a training mission, two Sikorsky HH-60G helicopters better known as Pave Hawks. It was a workhorse of the US Air Force, in use since 1982 and utilised in just about every military operation in the intervening years. While the Pave Hawk is now being phased out in favour of the Jolly Green II, the US Air Force alone still operates 99 Pave Hawks.

A key reason for this is that the Pave Hawk is designed to go places other aircraft won’t. It flies low, below radar coverage, hugging the terrain in what’s known in the military as nap-of-the-earth flight. The forward-looking infrared system makes them particularly well suited for night-time low-level personnel recovery operations.

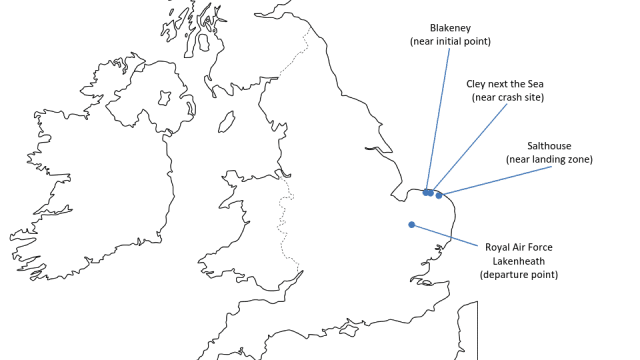

This particular Pave Hawk, tail number 88-26109, was assigned to the 56th Rescue Squadron, operating out of RAF Lakenheath as part of the United States Air Forces in Europe (USAFE)’s 48th Fighter Wing. The mission that night, the 7th of January 2014, was for the two Pave Hawks to fly in formation for a training scenario rescuing a downed F-16 pilot in the dark.

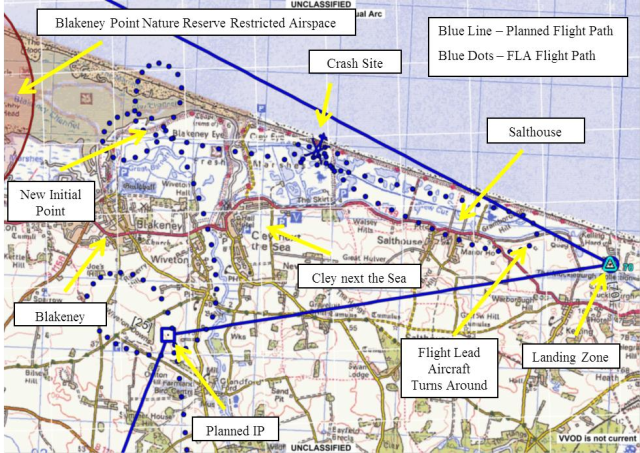

The pilot of the mishap helicopter and the co-pilot of the lead helicopter developed the mission plan the day before. All crew members would wear night-vision goggles. They would depart from RAF Lakenheath an hour after sunset and fly about 36 nautical miles to a point south of Blakeney. There, they would orbit, verify the status of the hypothetical downed pilot and conduct a threat assessment. The two helicopters would remain in formation and fly low-level for about three and a half nautical miles to a landing zone near the village of Salthouse, a site frequently used for training missions. At such low altitudes and in the dark, their options were limited. The planned routing had to avoid obstacles, air traffic and local noise-restricted areas.

The mission plan complied with all operational requirements and was authorised.

That same day, the day before the accident, the Wildlife Trust counted a flock of some 400 geese along with other birds roosting in the area.

The Blakeney Point Nature Reserve is a well-known habitat for large flocks of migratory birds and is designated as avoidance zone: “avoid by 500 feet or 2 nautical miles for flying options”. The UK Military Low Flying Handbook recommends that aircrew should cross coastlines at right angles and above 500 feet above ground level to avoid bird strikes. However, this mission was a nighttime tactical low-level formation, intended to be flown under the cover of darkness and required flying below 500 feet.

A month earlier, in December 2013, a storm surge had flooded the coastal marshes, including Blakeney Reserve. Several flocks of birds had moved southeast to roost on drier ground.

The crew had access to bird activity maps during planning. The December map showed moderate bird activity west of the landing zone at dusk. The January map, released the day of the training mission, indicated a low-level area of bird activity over the Cley Marshes. The crew had access to the maps for reference during mission planning. The maps indicated an area of moderate bird activity at dusk (defined as one hour before and after sunset) to the west of the proposed landing zone. As the mission departed after sunset and would arrive at the landing zone an hour after dusk had ended, this risk was considered mitigated.

The key point: All required procedures for evaluating risks and benefits were followed.

On the day of the crash, the Wildlife Trust counted zero geese.

The two-aircraft formation departed at 17:33: 90 minutes after sunset and half an hour after the end of dusk, half an hour after the moderate dusk bird hazard warning had expired. The helicopters flew north to start their simulated mission to rescue the hypothetical downed F-16 pilot under the cover of darkness.

On the way to the first point, they conducted simulated threat countermeasures. The helicopters arrived at the first point 25 minutes into the flight and started a left orbit, simulating a check on the downed pilot’s status.

High winds near the initial holding point, south of Blakeney, caused the formation to drift north towards the Blakeney Point Nature Reserve. Blakeney Reserve is a designated no-fly area and they were approaching the zones marked for moderate and severe bird hazards. The training profile meant that they were flying low, just 110 feet above ground level, which meant they were at risk of causing a noise disturbance if they got too close to populated areas.

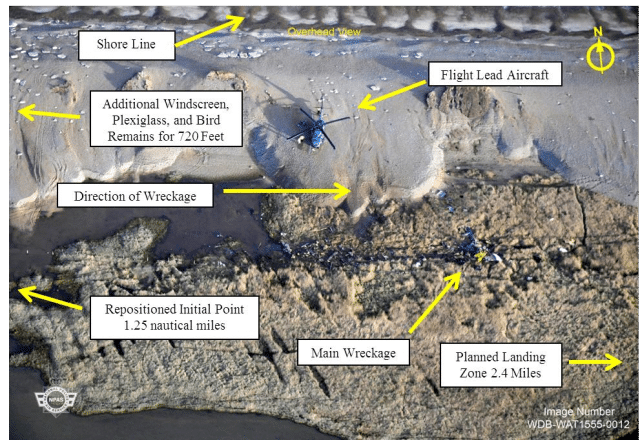

The lead helicopter pilot moved the orbit 1.3 miles to the north, establishing a new “initial point” closer to the coastline. This kept them clear of Blakeney Reserve and the known bird-hazard area. The new route kept them in an area marked with a “low” bird hazard rating, but also passed over Cley Marsh, part of a protected wildlife area.

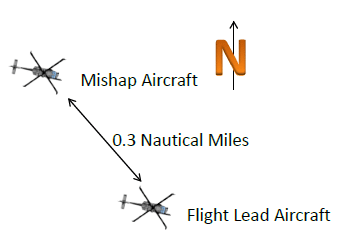

They reached the new initial point and completed two full left orbits. Then they exited the orbits to fly east at 100 feet above ground level at 110 knots indicated airspeed. The two helicopters maintained a 0.3 nautical mile separation, with the mishap helicopter positioned behind and to the left of the lead.

As they approached Cley Marsh, a flock of geese took to the air, likely startled by the noise of the engines. Within a minute, the birds had climbed to a height of 110 feet.

The Pave Hawk in the flight lead position, still about 0.3 miles ahead, did not see the geese at all. But behind them, the rising geese collided with the other helicopter. That type of goose weighs 6 to 12 pounds. At least three crashed through the windscreen and into the cockpit, knocking the pilot and co-pilot unconscious.

At least one goose struck the gunner in the open doorway, rendering the gunner unconscious. Another goose crashed into the nose of the helicopter, disabling the Trim and Flight Path Stabilization systems. The Flight Path Stabilization system dampens changes in pitch, roll, and yaw to keep the aircraft stable in flight. Both of these components are part of the autopilot. With the autopilot disabled, the stick fell to the left.

At this point, the Pave Hawk was in a furiously dangerous state: just 110 feet above the ground with the autopilot disabled and both pilots unconscious. It started to bank left until it hit a critical point and lost all vertical lift.

The only member of the crew who was still conscious was the flight engineer, who most likely never even realised what was going on. The report grimly notes that it takes 3.4 seconds for a human to perceive and process a sensory input.

Three seconds elapsed from bird strike to the crash.

The Pave Hawk was destroyed on impact, killing all four crew members.

All of the crew were wearing full helmets which were designed to withstand a force of 150Gs. All of the helmets were cracked from the force of the impact. Feathers were found inside and outside of the helmets.

The report notes that a slightly below average goose, weighing about 7.5 pounds, would impact with, as an oddly specific comparison point, 53 times the kinetic energy of a baseball moving at 100 miles per hour. The geese exceeded the design tolerance of both the windscreen and the helmets, delivering over 300 Gs of force on impact.

The United States Air Force Aircraft Accident Investigation Board ultimately concluded that the accident was caused by multiple bird strikes – but offered no contributing factors that could have mitigated the risk. They found no evidence that the mission planning or supervision of the planning contributed to the mishap.

The crew were briefed on the bird activity in the areas, with up-to-date reports of bird activity in the area. These referenced heightened bird activity at dusk, but as they were operating after dusk, there was no reason to consider this a concern. The night vision goggles restricted the crews’ field of vision, which could have stopped them from seeing the geese taking flight. But then, it’s impossible to say that the geese would have been visible by the naked eye in the dark, let alone whether there was time to do anything about them.

It’s a brutal demonstration of just how lethal a bird strike can be, destroying four lives and a $40 million aircraft in seconds. Ultimately, the Air Force can only hope it doesn’t happen again.

One wonders if it might be a good idea to measure bird activity After a military helicopter has just flown over them at 100 knots and 100 feet altitude.

Unlike human beings, whose responses to that sort of thing are generally limited to angry phone calls, geese are in a position to do something else about it.

J.

And some people worry about drones or UFOs… ;-)

I was thinking that maybe we should invest in a squadron of trained attack geese for air defence…

I would never assume that a bedded-down bird, would stay bedded down, after a low level helicopter fly-by. I think that would scatter most critters, and when your instinct is to fly to safety…

I live in an area with lots of non-migratory geese. I’ve never tried to disturb them in the nighttime(*) so I don’t know for sure how easy it is to rouse them, but ISTM that flying a very noisy aircraft a hundred feet above sleeping geese is only slightly less hazardous than flying that close to them in daytime; sleeping soundly is not a survival tactic for a prey species. This isn’t the sort of thing pilots would necessarily think about, but I’m surprised that the final findings don’t criticize the supervision; shouldn’t somebody on the ground have drawn full-time borders around this area?

I’m also wondering about the lead pilot’s decision to move the “initial point”; shouldn’t countering local winds in order to stay in the assigned territory be part of the job? (I remember having to do pivot turns around a point on a windy day, increasing or decreasing bank as necessary to stay on point, as part of getting a private license in a plane that cruised about half as fast as a Pave Hawk; I’d hope the pilots knew how to do this even at night.) I can just imagine the reaction to a rescue team saying “We decided to land 1.3 miles away from the pickup because we got blown off course.”

(*) IIUC, private citizens disturbing geese is forbidden by various levels of law even though they’re a nuisance such that official efforts at control (border collies to keep them out of parks, twaddling or oiling their eggs to reduce their numbers) are approved.