No one noticed it was missing: 1971 Super Cub crash

Lasham Aerodrome in Hampshire, England, was built in 1942 and used as a base for the RAF Fighter Command. After the war, it became the home of the Army Gliding Club. That year, the Surrey Gliding Club and the Imperial College Gliding Club also moved to Lasham, as their aerodromes were becoming too busy for gliding. The Lasham Gliding Society was established in 1958; it is now the largest British gliding club in existence and one of the largest in the world. Powered aircraft at Lasham are rare, with an obvious exception of tugs for the gliders, and inbound flights need special permission unless there is a genuine emergency.

In 1971, the Lasham Gliding Society had four light aircraft that they leased from Air Tows Limited. There were a small number of pilots who flew the aircraft on behalf of the club. Many of the pilots were also glider pilots. When the aircraft were not needed for towing, the pilots were encouraged to use them for private flights.

At the time, many small airfields had a book in which pilots would log their departure and then sign off upon their return. However, as most of the flights at Lasham Gliding Society were short, local area flights for towing, they did not have such systems in place and did not keep a booking-out book. Each aircraft had a log in which the pilots noted all flights, which was handed into the office at the end of the day. However, the Society were not required to keep a record of tug movements and they did not do so.

If a pilot wished to take one of the tugs for a private flight, all he needed to was obtain verbal authorisation from one of the Society officials.

One of the tug aircraft was a Piper PA-19 registered in the UK as G-AYPN, owned by Air Tows Limited and operated by the Lasham Gliding Society. Piper initially designed the PA-19 as a military variant of the PA-18, in response to the US Army’s call for liaison aircraft. Three prototypes were built. The third had an upgraded engine, a Continental C-90-12F, which set the ground work for the finished product. Piper did not immediately get the expected military orders and considered releasing the aircraft for civil use, which may be why they reverted to the PA-18 designation: once in production, the military variant became known as the L-18C Super Cub.

In the end, the US Army purchased around 700 of the L-18C with another 156 going to other nations for military use. However, when Piper L-18C aircraft moved from military service to the civil register, they once again were assigned the PA-19 designation.

This specific Super Cub had originally been purchased by the French Light Air Force. It had been imported into the UK that same year and added to the British Register as a PA-19 on the 13th of July 1971. The aircraft did not have IFR instruments and there was no radio equipment.

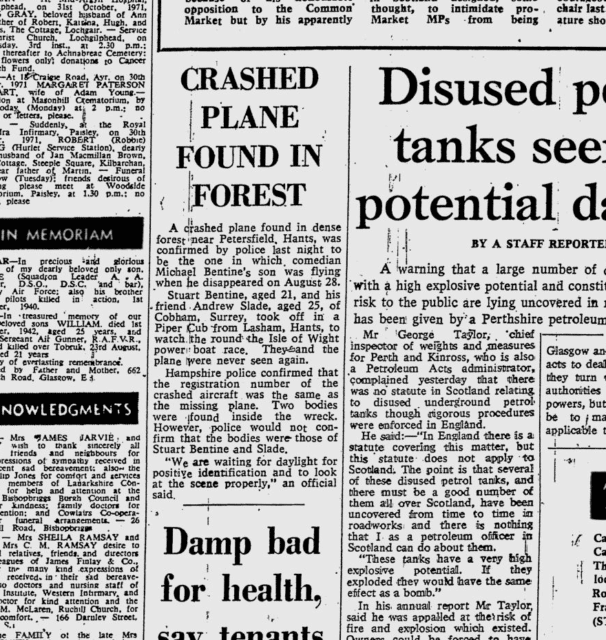

On the 28th of August in 1971, G-AYPN departed Lasham Gliding Society and disappeared.

In the front seat was a 25-year-old private pilot with 94 hours flight time, of which 31 had been on Super Cubs, towing gliders for the Society. He was also a qualified glider pilot. He was not rated for night flying or for instrument flight. In the back seat was a non-pilot friend. The pilot mentioned at the airfield that they were thinking about visiting Sandown aerodrome on the Isle of Wight.

That Saturday morning, the daily weather forecast was up on the notice board, warning of strong winds and low clouds with a base of 700 feet.

The pilot usually phoned from home to get the weather forecast before leaving for the aerodrome, but it is not clear if he did that day or if he saw the forecast on the notice board.

The Super Cub had between 15-20 gallons of fuel on board. The pair took off heading west on runwway 27 at 11:30 local time. They continued west bound as they climbed away and disappeared into cloud at about 700-800 feet.

The visibility that day was variable, with a warm, moist and cloudy airstream covering the area. To the north, the cloud base was between 1200 and 1800 feet. To the south, the cloud base was as slow as 500 feet with the occasional drizzle. Mist and fog covered the tops of the South Downs.

The Super Cub reappeared below the clouds and turned left. For a moment, it seemed that the pilot was flying a left-hand circuit to land. Then, on final approach, the pilot again began to climb away. Staying just under the cloud base, he again turned left but this time the aircraft didn’t join the circuit but continued flying south.

The following morning, a club member reported to one of the Society officials that the Super Cub was not in the hanger. That afternoon, another club member spoke to the same official and mentioned that a Super Cub was missing. The official was not surprised by the news; the Society had a Super Cub out on loan for a week, which was returned around lunchtime that day. Then, later that afternoon, a different Super Cub departed for Blackbushe. Thus, both times when a Super Cub was reported missing, the official was aware that there was a Super Cub known to be elsewhere. He presumed that the reports were referring to one of these two aircraft. No one ever thought to mention that, at the time of both reports, there were two Super Cubs missing.

That evening, around 20:30 local time, the pilot’s sister phoned the club to ask about his whereabouts. it was unlike him to be away from home with no message. All of the staff had already left for the day and the person who answered the phone wasn’t able to help.

She phoned again on Monday morning and explained that her brother had now been missing for two nights and she was worried. At the same time, the duty flying instructor realised that G-AYPN was not in the hangar and there was no record of it being used elsewhere. He was able to confirm that the pilot had checked it out on Saturday but only now had they realised that he’d not returned.

They phoned Sandown aerodrome on the Isle of Wight. The aircraft was not there. Sandown requires prior permission, but they had not received a request for any inbound aircraft from Lasham. Not only was the aircraft missing but no one knew where the pilot had intended to fly to.

The Lasham Gliding Society manager phoned Basingstoke police and the duty officer at the Department of Trade and Industry to ask if there had been any reports of a forced landing or crash.

There were none.

Somewhat relieved, the Society officials considered that perhaps the pilot had simply borrowed the aircraft for the weekend without asking permission. Someone mentioned that the pilot might have flown to Scotland.They waited until dusk, hoping the Super Cub would appear and it would all be a big laugh.

As the light faded from the sky, so did the hope. The Society manager officially reported the flight as overdue. The report went to the the Basingstoke Police, the Department of Trade and Industry, London Air Traffic Control Centre and the Royal Air Force Rescue Co-ordination. The report stated that the Super Cub had departed Lasham at 14:00 on Saturday with enough fuel for about three and a half hours flight, destination unknown. It’s not clear where the new time came from; the Super Cub departed the airfield at 11:30.

London Air Traffic Control passed the details to ATC Centres at Preston and Redbrae, as well as the French Airways Supervisor in Paris. Without knowing where the pilot was headed, there was little that they could do. They were informed that a televised power boat race showed a yellow aircraft flying overhead, but when the footage was obtained from the BBC, it was not the missing Super Cub. At some point on the following day, the Lasham Gliding Society contacted the Centre to correct the departure time from 14:00 to 11:30.

The Rescue Co-ordination Centre was also unable to take any practical action without knowing where to search. They contacted the Coastguard and other ships asking for any sightings of the aircraft. On the 3rd of September, a member of the public reported to the Hampshire police that they’d seen an aircraft north of Midhurst. The Rescue Coordination Centre searched the area, but nothing was found.

The Basingstoke Police were the first to know that there was a missing aircraft, as the Lasham Gliding Society manager had phoned to ask about any reports of a forced landing or crash. They passed the information that an aircraft had gone missing to all Hampshire stations, including the Aldershot police, who are responsible for Lasham and the surrounding area. That evening, they were notified that the aircraft was officially overdue.

An Aldershot police officer was asked to supervise the enquires and a general alert was broadcast to all stations. On Tuesday, the 31st of August, the details of the missing flight was featured in local newspapers and broadcast on television. People phoned in from all over the country to see that they’d seen the plane. The police had the task of filtering through these sightings and following up on those that seemed signicant. Usually, the reports and analysis would be done in conjunction with the Rescue Co-ordination Centre but the police station had not dealt with such a situation before and worked through the incoming reports on their own.

One person on the northern outskirts of Petersfield reported seeing the Super Cub low beneath the clouds, about 200-300 feet above the ground, flying south. Another phone call reported that two of them had been in the village of Buriton when they’d noticed the Super Cub flying south towards the Buriton railway tunnel. They said that the aircraft was visibly rocked by turbulence but didn’t appear to be in difficulty.

The railway runs south through a valley. That day, the cloud base was about 600 feet above mean sea level with a light drizzle. The horizontal visibility was around half a mile.

Both of these reports stated that they’d seen the aircraft around noon. As a result, they were dismissed, as the initial report from Lasham said that the aircraft had not departed the airfield until 14:00.

It’s not clear when the police discovered that the actual departure time was actually two and a half hours earlier, at 11:30. It definitely came up during a phone conversation on the 3rd or 4th of September, but that was as a secondary detail, not the point of the phone call. The police officer noted the information but it did not occur to anyone that the public sightings should be revisited to see if any had been dismissed based on timing.

Of all of the reported sightings, only two were actually of G-AYPN. But they were dismissed as having occurred before the aircraft had departed. As the police attempted to retrace the steps of the aircraft, they knew only that it had departed from the airport and flew south, keeping below the bad weather.

A number of private pilots from Lasham and Blackbushe attempted their own aerial reconnaissance, exploring the South Downs and the New Forest in hopes of finding signs of a crash. They found nothing.

There was another witness who was standing on high ground over the railway tunnel and saw the Super Cub flying low over the trees. The aircraft tilted left, as if hit by a gust of wind. Then it continued south down the valley, remaining under the low clouds. As it disappeared into the distance, it sounded as if the engine had changed notes, as if the engine power had been increased. Then a train passed by, drowning out any sounds from the aircraft. This combination of low flying and increased engine worried the witness, who noted that the time was 12:12 exactly. He walked to the woods to have a look around. There were no signs of a crash.

September passed and then October. Autumn came and the leaves began to fall. On the 31st of October, two months after the flight had disappeared, a member of the public walking along a track through the forest saw the wreckage about 50 yards away. It was in a heavily wooded area about four miles south of Petersfield and just one mile south of the Buriton railway tunnel. The accident site was 15 nautical miles south of the aerodrome and at an elevation of 475 feet above mean sea level with young beech and ash trees of 45-50 feet.

Only three weeks before, the same person had walked that same track and seen nothing. Employees of the Forestry Commission had passed very close as well but again, in the dense foliage, they did not see the wreckage.

The Super Cub had dived into the forest with a westernly heading, the nose and the port wing at an angle of 70° down. Travelling at 60-70 miles per hour (96-112 kmh), it impacted nose first, almost vertically. There was no trail of damage on the tree tops which might have attracted the attention of the aerial searchers. There was no fire.

The two men were found still strapped in their seats, heavily decomposed. There was nothing obviously wrong with the aircraft, other than the filler cap to the port fuel tank was missing. It was impossible to prove when it had come off, but it didn’t really matter. The fuel selector was set to the starboard tank, which had still held fuel when it ruptured on impact. A subsequent aerial search showed that the wreckage could not be seen from the sky and would not be visible until most of the leaves had fallen.

More damning was a fatigue crack in the cabin heater’s heat exchange unit. The heat muffler had deposits of lead and bromine on the heater muffler’s exhaust, left behind by the high octane fuel fumes which had seeped through the cracks into the heater system. The exhaust unit had been pressure tested in May and visually examined in June and again in August. Since then, it had flown a total of seven hours flight time. The heater system controls were set to off but that wasn’t necessarily meaningful; the levers had been struck on impact such that they would have been forced closed if open.

So what do we know?

The Super Cub departed southbound and was seen passing north of Petersfield and over Burinton towards the Buriton railway tunnel, flying low and struggling with turbulence.

The railway runs south from Petersfield through the Buriton railway tunnel below high ground of about five hundred feet above mean sea level and then south through the valley, with hills reaching 650 feet above mean sea level. About half a mile beyond the tunnel, there is a line of power cables crossing the track from north east to south west. The tops of the pylons carrying the cables are at 575 feet above mean sea level.

At 12:12, an eye witness saw the Super Cub flying low over the tunnel and into the valley, following the line of the tracks. At that time, the clouds were about 600 feet above mean sea level which put them at the same height as the power cables across the valley.

The power cables were not marked on the pilot’s chart.

That last sighting was accompanied by a change in the engine note as it disappeared into the distance, a change that the witness associated with a burst of power.

A scenario presents itself. The pilot is flying low, attempting to remain in visual conditions. At the last minute, he saw the cables in his path and pitched up steeply while increasing the engine power. As they climbed safely over the cables, the Super Cub entered the clouds. Only moments earlier, the aircraft had seen to be bouncing in the turblence. With no visibility, no instrument training and only minimal instruments, the pilot quickly lost situational awareness. Soon, he literally no longer knew which way was up. Perhaps he meant to descend in order to regain visibility; however, there is no chance that he meant to descend so steeply, knowing that he was just over the trees. By the time that they were clear of the clouds, the Super Cub was diving through the tree tops, seconds from impact.

Still, it seems odd for the pilot to have continued the flight in the first place. It was clear from the start that the clouds were low enough to make it difficult for a visual flight. Indeed, initially the pilot appeared to turn back, lining up to land back at Lasham after accidentally flying into the low cloud.

The crack in the heat exchange unit may have also played a role. If there were exhaust gases in the cockpit, then the decision-making skills of the pilot could have been strongly impaired. This would affect every aspect of the flight, from the decision to carry on just a few hundred feet above the ground to losing control once they’d flown over the power cables. Unfortunately, there’s no way to know if the heating was on that Saturday, throwing fumes into the cockpit. As the wreckage was not found for two months, the postmortem analysis gave very little information.

The two occupants clearly died on impact, so a speedier response from search and rescue would not have otherwise made a difference. However, it isn’t difficult to imagine a scenario where they may have been injured and in need of help. A speedy response requires that search teams know as soon as possible that a crash may have occurred and at least an idea where the crash may have occurred.

The lack of procedures for private flights from Lasham caused this final failure. The only control was the verbal agreement from an official, with no paper trail. Once it was clear that the Super Cub was missing, that person had to be found and in this instance, he or she did not know where the pilot was taking the aircraft. A system that was “good enough” for short local area flights with gliders made it impossible to determine that the pilot and plane were overdue, in the first instance and then left search and rescue teams with no way to organise useful ground or aerial searches.

The final report by the Accidents Investigation Branch in the Department of Trade and Industry concluded that there was nothing wrong with the aircraft.

The aircraft was flying low in poor visibility in a valley obstructed by high tension power cables. In avoiding the cables, the aircraft went into cloud and the pilot, inexperienced in instrument flying, was unable to maintain control without blind flying instruments. The aircraft dived into a dense wood in a steep nose-down and port wing down attitude.

Cause

The aircraft, which was not equipped for instrument flying, went into cloud when taking action to avoid power cables while flying low in poor visibility and subsequently went out of control.

They made three recommendations:

(1) That consideration be given to a requirement for flying clubs or groups to maintain a log and adequate supervision of their powered aircraft’s activities.

(2) That all police authorities should include in an appropriate form in their disaster orders the relevant details of the search and rescue facilities as published in the United Kingdom Air Pilot.

(3) That consideration be given to the development of a reliable carbon-monoxide detector for aircraft cabins.

As a side note, the passenger was the eldest son of the British comedian Michael Bentine, who became interested in the regulations governing private airfields as a result of the crash. He continued to investigate this in the context of smuggling operations using personal aircraft and wrote a report on the subject for the British police department known as Special Branch. The material he collected for this report formed the basis of his novel Lord of the Levels.

Thank you to Peter Michael Rhodes for his fantastic photograph of G-AYPN at Lasham, taken just a few months before the crash.

Another riveting write-up, thank you, Sylvia!

As I was reading, I wondered: what distinguishes an airfield from an aerodrome from an airport? These three terms seem not exactly synonymous, but appear to have considerable overlap in their meaning.

Is there a CO detector requirement for general aviation? I recently got a CO monitor for my garage and it’s a very small cigarette-pack size unit.

There is no real comment to make here. The reason why the pilot decided to leave the traffic pattern of the aerodrome will probably never be known.

What is very likely is that the pilot got lost, but that can already gleaned from Sylvia’s blog here. His total flying time was not really great, not enough to embark on a cross-country flight in very marginal weather

Eventually he probably got vertigo, or maybe he became victim of fumes from a broken heater. Although, who am I to write that? I completed my first solo cross-country flight in weather conditions that were no better, over the Nigerian jungle. With a map that had large white segments with the comment: “No relief data due to incomplete survey.”

All I can comment is: my stupidity only resulted in a few weeks’ grounding by my instructor. I was just lucky. Very lucky.

The difference between an aerodrome and an airport is not really very clearly defined. We refer to an airport as a piece of real estate with one or more paved runways, usually taxiways, some infrastructure like a terminal building or a restaurant, generally open to the public and some form of control tower. Usually it supports commercial flight operations, It need not have a control zone, but anything less starts getting in the realm of “aerodrome”. Of course, places like London Heathrow, Paris Charles de Gaulle, Frankfurt am Main, Amsterdam Schiphol, Madrid Barajas, John F Kennedy NY, etc, are all large airports. We know for sure that they are not “aerodromes”. But where does an aerodrome become big enough to be called an airport?

An aerodrome therefore is a place, usually licensed for public flight operations, mostly in the form of (light) private aviation. It may have a paved runway, but does not usually support commercial flights. The runway, or unpaved landing area itself is typically no more than 1000 metres long.

Then there are small airfields, typically owned by a local private operator or flying club. Permission to operate into, or out of them, must be obtained from the operator by prior arrangement.

These are rough descriptions as I have come to regards them, these are not definitions. That is why I needed so many words to describe them.

Very interesting, well researched, thank you for another great blog post Cynthia. The history of flying is always interesting to me.

It amazes me that a lot of us that learned to fly in the ’60s survived long enough for the ink to dry on our Pilot’s Certificate.

Just across the railroad tracks from my grandparents business the 2 lane highway had a 1/2 mile straight stretch with no power lines crossing it. When I was a kid a friends father would land Crop Dusters on it to refuel and top up the spray tanks. I thought, if you can operate a Crop Duster off the highway, why not a private plane?

After getting the Solo permit, I would go to visit and land there, 1st in a Super Cub and later in a Luscombe. One clearing pass to see there were no cars on the road, taxi up into the parking lot of the Baptist Church and it was only a 2 block walk to grandmother’s house.

No flight plans were filed, neither of the planes had radios and the weather briefing was listening to the local AM radio station.

With operations run as loose as they were 50 years ago, flight safety came down to the common sense of the pilot and a lot of luck. Luck ran out for this pilot and his friend.

I’m amazed that flight operations in England were so informal, even half a century ago; the US image of England tends to involve a lot of order, rather than daredevil flyers (at least outside the RAF). I suspect that once you get away from centers of population (into the less-settled areas where private flying is a useful way to get from place to place), a lot of more-careful practices become less common; some of the experiences above seem completely alien to my flying days, which were based just outside Boston.

A comment on nomenclature. I don’t think I’ve ever heard/seen “airdrome”/”aerodrome” used outside of historical descriptions — although this may be biased by my being relatively urban. But I’ve just finished first-time author John Lancaster’s The Great Air Race: Glory, Tragedy, and the Dawn of American Aviation (about a cross-country-and-back demo/race set up by Billy Mitchell in 1919), which says that “airdrome” was used for fields that were relatively near communities (rather than just being convenient to the route between Long Island and San Francisco). I see “field” being used for any size of landing area that doesn’t have major scheduled services, e.g. the 2nd-most movements in New England are at Hanscom Field, which supports lots of general aviation but only ~10,000 “boardings” per year — more flying traffic but much less human traffic than airports at Manchester, Providence, or Windsor Locks (“Bradley”). OTOH much smaller nearby operations at Lawrence and Norwood call themselves airports. (Lawrence doesn’t even have a tower; “airport” may be a hangover from when Northeast Airlines flew DC-3’s to New York City, over 60 years ago.)

I’m possibly the last person alive today that witnessed the aftermath of the plane crash that killed Stuart Bentine and the pilot.

I was 17 years old at the time and along with the funeral director we retrieved both bodies from the crashed aircraft.