MH370 Report : Where Did It Go?

On Monday, the The Malaysian Safety Investigation Team for MH370 released their SAFETY INVESTIGATION REPORT to the public. They have been careful to state that this is not a final report, with the argument that a final report is not possible under the current circumstances, where the victims and the bulk of the wreckage have not been found. But realistically, it is the equivalent: the investigation team is finished unless compelling new evidence comes to light.

Not surpringly, the report does not offer any answers to what happened on Malaysia Airlines flight 370 or why the Boeing 777 turned back from its flight path. But one answer that the Malaysian report does give us is how the aircraft was so completely lost, with satellite data never before used finally giving us an approximate location days after the disappearance.

There’s a lot of information in the report that is worth consideration but today what I want to focus on is that aspect of the case: how did the aircraft manage to disappear in the first place?

I’m not sure it’s necessary to go over all of the details but, for the sake of completeness, I’ve included the main events with a focus on the facts confirmed by the report.

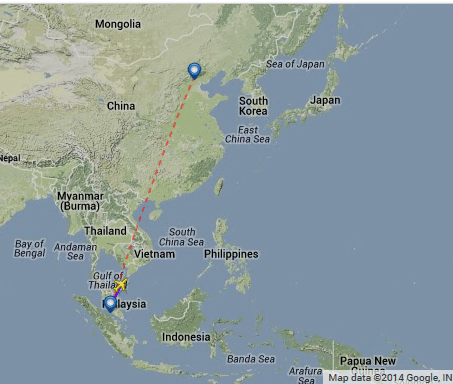

On the 8th of March 2014, Malaysia Airlines flight 370, a scheduled passenger flight from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia to Beijing, China, departed Kuala Lumpur normally. The as-the-crow-flies distance is 4,392 kilometres (2,745 miles). This overnight flight standardly departs Kuala Lumpur at 00:25 local time with an expected arrival in Beijing six hours later at 06:35. Both Kuala Lumpur and Beijing are eight hours ahead of UTC. I have taken the liberty of using local time rather than UTC as the timing — the incident took place in the early hours of the morning in all of the relevant areas, in the window of circadian low — is relevant to the mistakes that happened.

The Boeing 777 was registered as 9M-MRO. It was twelve years old and had the capacity to take 282 passengers (35 business seats and 247 economy seats).

There were 227 passengers on board. The seven page passenger manifest shows the name, nationality and age of each of these passengers, ranging from passenger #162, Wang Moheng, Chinese, age 23 months, to passenger #92, Lou Baotang, Chinese, age 79. Little Wang Moheng was returning from his first trip abroad, a family holiday to Malaysia. The twelve crew members were all Malaysian citizens.

In south-east Asia, all conversation between controllers and pilots is in English. The official transcript of the pilots of Malaysia Airlines flight 370 (MAS 370) and the air traffic controllers (ATC) at Beijing started just after midnight at Kuala Lumpur International, when they contacted ATC Clearance Delivery for their route clearance to Beijing.

Initially, the first officer spoke on the radio until take-off, at which point the captain handled ATC communications. This means that the first officer was almost certainly the Pilot Flying: he had been assigned to be the flying pilot for that sector and was due for a check flight on his next duty assignment.

The Boeing 777 took off at 00:42 local time. As per normal procedure, Kuala Lumpur Area Control Centre (ACC) contacted Ho Chi Minh ACC via land line and told them Malaysia Airlines flight 370’s estimated time of arrival at waypoint IGARI of 01:22, based on the flight plan, and requested FL350 (35,000 feet) for the flight’s cruise altitude, which was approved.

The IGARI waypoint is important because it is the point where responsibility for the flight is passed from Kuala Lumpur ACC to Ho Chi Minh ACC. When the Kuala Lumpur radar controller sees the aircraft over IGARI waypoint on the radar display or when the flight crew report that they are over IGARI, the controller will tell the flight crew to contact Ho Chi Minh. There’s no ‘electronic handoff’ between Kuala Lumpur and Ho Chi Minh and they do not have a system for notifying each other of the transfer of control. Once Kuala Lumpur notified the flight crew that they should contact Ho Chi Minh, control is transferred.

The climb and initial cruise were uneventful until Malaysia Airlines flight 370 approached the IGARI waypoint.

The radar controller saw that the aircraft was reaching the edge of his Flight Information Region (FIR) and instructed the flight crew to contact Ho Chi Minh on frequency 120.9. The captain responded at 01:19:30 with “Good night, Malaysian Three Seven Zero.” This was the last communication from the aircraft.

This isn’t a good readback but it’s not uncommon, especially if things are busy on the flight deck. Voice sample analysis foiund no evidence of stress or anxiety in the statement, although it is the first instance (of three) where the frequency was not read back (repeated by the captain to confirm they have the right frequency).

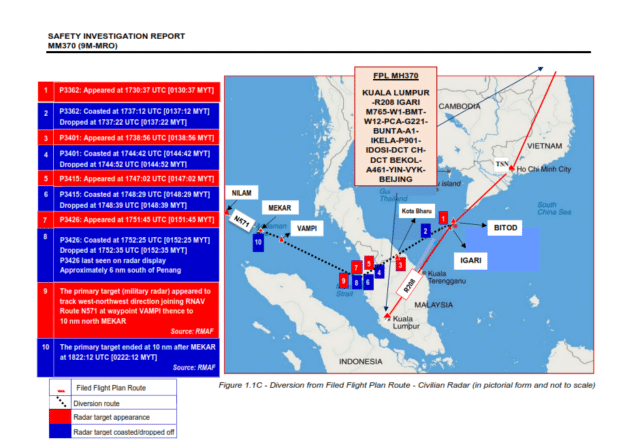

The timing is all pretty tight. The estimated time for the transfer of control was 01:22. The actual transfer of control was 01:19:30. Radar recordings show that the aircraft passed over IGARI was 01:20:31. And at 01:20:36, the Mode S (secondary) radar symbol of Malaysia Airlines 370 disappeared from Kuala Lumpur’s radar display. That is, this is the point that the transponder was either turned off or failed. The display also disappeared from Ho Chi Minh and Bangkok’s radar displays at that time. No one reacted.

Malaysia Airlines flight 370 had stopped communicating and had disappeared from secondary radar displays but what no one knew at that point was that it had also diverted from its planned flight path and was now turning back towards Malaysia.

However, the Boeing 777 still appeared on Military radar, which does not rely on the aircraft wishing to be seen (the transponder) but instead emits a pulsed beam of radio waves and looks at the reflections. Radar recordings from that time show that at 01:21:13, the aircraft turned right and then began a constant left turn to heading 273°. You can see the planned route (red line) and the diversion (dotted black line) on the map below.

As a part of the investigation, the team ran through a number of flight simulations in order to recreate how Malaysia Airlines flight 370 initially diverted from its flight path. They knew that the aircraft made a left turn just past waypoint IGARI. Using radar returns, they were able to set up entrance and exit waypoints to reconstruct the flight path for that section of the flight which they knew took the Boeing 777 two minutes and ten seconds to achieve. With that information, they were able to test multiple configurations to attempt to find out more about the state of the aircraft as it made the turn.

The simulations showed immediately that, although the manoeuvre could be done using the autopilot and flight management systems, it could not be completed in under three minutes. This is because the maximum bank angle using the LNAV (lateral navigation) is 25° and in order to complete the manoeuvre in less time, a steeper bank angle was needed — the simulation which came closest to following the known path of the aircraft involves a steep turn with a bank angle of 35° and an indicated airspeed of 250 knots. In recreating this, the investigators noted that bank-angle warnings sounded several times and the stick-shaker activated about halfway through the turn.

This tells us a very important point: the aircraft was under manual control at that point. It was not following a programmed route. The autopilot was disengaged.

Investigators also confirmed that the manoeuvre could be performed by a single pilot.

The flight path after the steep turn was consistent with on-board navigation systems in use (LNAV or heading mode) to follow a set of waypoints, that is, the manual control was likely only used for that turn.

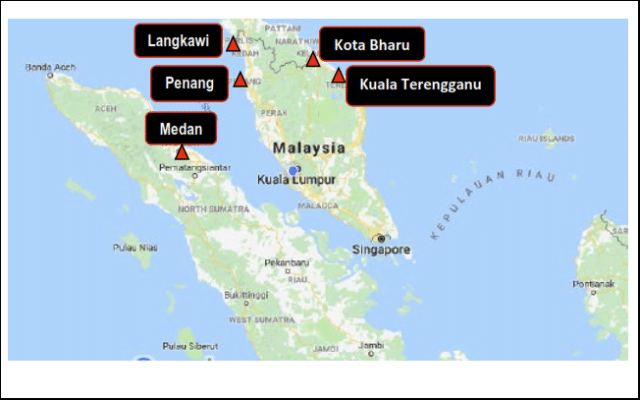

The Boeing 777 then continued south of Penang where it turned towards waypoint MEKAR. This turn could easily have been completed by turning gently using heading mode. Throughout this, there are no rapid altitude and/or speed changes which might indicate that the pilot was evading radar.

The next and final turn to the south is the one we know very little about. Ten nautical miles north of MEKAR, the aircraft disappeared from radar at 02:22 local time and some time after that (shortly after it passed the southern tip of Sumatra) it changed course.

Now we know that the aircraft did not actually crash until much later; the final ‘handshake’ of the aircraft Satcom system connecting to the Inmarsat satellite was at 01:15UTC which is 09:15 Malaysian local time. This means that almost eight hours elapsed from the time that the Malaysian Airlines flight 370 diverted off course to last known evidence of the aircraft with power.

Under normal circumstances, if an aircraft fails to make a position report when expected, then no later than three minutes after the estimated reporting time, the controller should:

- confirm the time of last contact

- request information from other Air Traffic Services units and likely aerodromes

- Notify the Rescue Coordination Centre that the Uncertainty Phase exists

Loss of radio contact with an aircraft under Air Traffic Services control is a trigger event and if contact is not established, then an Uncertainty Phase is declared, signalling that uncertainty exists as to the safety of the aircraft and its occupants. The aircraft was estimated to pass IGARI at 01:22, so it would have been possible to declare the Uncertainty Phase as early as 01:25 and certainly no later than 01:55. Within 30 minutes, the phase is updated to Alert Phase (apprehension exists) and then after at most a further 30 minutes with no contact, the phase is updated to Distress Phase (reasonable certainty). This means that Search and Rescue operations would have commenced before 3am, not long after the aircraft had turned south.

But this didn’t happen.

At 01:39 Ho Chi Minh air traffic control contacted Kuala Lumpur to ask about MH370, stating that the flight crew had not made contact and that the aircraft was last seen at the BITOD waypoint.

This was incorrect. The BITOD waypoint was the next point on the aircraft’s planned routing, but the aircraft had not made that far and the secondary survellience dropped just after IGARI. It would seem that the radar operator was only half paying attention and had not realised when it disappeared off the display.

Kuala Lumpur confirmed that the flight had not returned to the Kuala Lumpur frequency, which would be standard procedure if an aircraft is handed off and can’t make contact on the new frequency. The Kuala Lumpur control called Malaysia Airlines 370 on their frequency but received no response.

Ten minutes later, Ho Chi Minh queried again, as they had had no verbal contact with Malaysia Airlines flight 370, despite repeated calls and requests to other aircraft to relay, for a period of twenty minutes.

Twenty five minutes had elapsed. This would been a good time to set the Uncertainty Phase, or even, considering the aircraft had disappeared from radar and not been heard from since, jumping straight to the Distress Phase. Instead the two stations continued with their attempts to make contact with the aircraft, checking in with each other to see if anyone had heard from the flight crew.

The responsibility for alerting lies firmly with Kuala Lumpur, as the service who was last in contact with the aircraft.

At 02:00, the Kuala Lumpur radar controller asked a junior officer to inform the Air Traffic Services Centre Duty Watch Supervisor, who was in the rest area next door, that Ho Chi Minh air traffic services have queried the status of Malaysia Airlines flight 370, because they have been unable to make contact.

The Duty Watch Supervisor returned to the Air Traffic Services Centre immediately. He contacted Malaysia Airlines Operations Despatch Centre and informed them that Ho Chi Minh had not established radio contact and did not have radar contact.

At this point the Boeing 777 had overflown Malaysia, where nobody was looking for it, and was still being tracked by military radar. One radar operator noticed it. He confirmed it was a civilian flight and thus ‘friendly’. He did not take any further action as he had no idea there was any cause for concern.

Meanwhile, at Malaysia Airlines, the Operations Despatch Centre reassured the Air Traffic Services Centre supervisor that the airline’s flight following system showed that the aircraft was in Cambodian airspace. He said that he would try to use the ACARS system to contact the flight crew and request that they contact Ho Chi Minh.

The Duty Watch Supervisor, having fulfilled his obligations and reassured that the aircraft was still flying, returned to the rest area at around 02:30 until about 05:30.

The Kuala Lumpur controller contacted Ho Chi Minh to let the controller there know that Malaysia Airlines Operations confirmed that the aircraft was still flying and was somewhere over Cambodia.

Ho Chi Minh, to their credit, queried this, standing that Phnom Penh, whose flight information region MH370 would be overflying, had no information on the aircraft. The Kuala Lumpur controller knew nothing more.

At 02:35, Malaysia Airlines Operations Despatch Centre said he was only getting updates every 30 minutes but confirmed that the Boeing 777 was still en route to Beijing as per its flight plan and had just updated to a location east of Vietnam.

Both controllers found this odd, as no one in Vietnam or Cambodia had heard anything from the aircraft. They tried again to contact flight 370 on various frequencies and asking other aircraft to relay the message. Kuala Lumpur asked the Ho Chi Minh controller if they were taking ‘Radio Failure’ action, but the Ho Chi Minh controller didn’t seem to understand the question. The Ho Chi Minh controller’s English, the report points out, was very poor, and their interviews with the controller had to be done with the aid of a translator. The Ho Chi Minh controller suggested that Kuala Lumpur contact Malaysia Airlines Operations, which Kuala Lumpur air traffic control had already done.

At 03:30, someone at the Malaysia Airlines Operations Centre finally realised that they had made a big mistake. Malaysia Airline’s flight following system, called Flight Explorer, is a computer-based system which tracks aircraft based on their flight plan data which is input into the computer. The system generates the flight profile and position of the aircraft and updates every thirty minutes. What it doesn’t offer is real-time tracking.

The person on duty that night didn’t really understand how the system worked and admitted later that he had not been properly trained in how to use the system. This seems likely, as when investigation team asked the Operations Despatch Centre for a copy of the flight following system’s User Manual, they were informed that there was none in the office. Later, a copy of the manual was delivered to the investigators.

The staff member on duty passed on the position reports for Malaysia Airlines flight 370, because he believed that the system was giving him actual positions. He didn’t understand that the position reports were simply projections based on the flight plan. The computer only knew where the Boeing 777 should be and had no idea where the actual aircraft was.

And now, neither did anyone else.

The radar controller at Kuala Lumpur broke the news to the Ho Chi Minh controller and asked if he’d checked with Hainan, which was the next Flight Information Region (FIR) where Malaysia Airlines flight 370 would have been expected to check in. The Ho Chi Minh supervisor now got involved, asking Kuala Lumpur to clarify exactly where the last known position of Malaysia Airlines flight 370 was.

Everyone on the planned route was contacted to see if the aircraft had maybe been in touch, including Sanya, Hong Kong and Beijing. No one had seen or heard anything from the flight.

At 05:30, the Duty Watch Supervisor returned to the Air Traffic Services Centre and informed the Kuala Lumpur Aeronautical Rescue Coordination Centre of the situation. Ho Chi Minh contacted Kuala Lumpur again, asking if there were any updates. And then at 06:10, the Kuala Lumpur controller contacted Ho Chi Minh, this time to ask if they, Ho Chi Minh, had initiated Search and Rescue procedures. They had not.

At 06:32 local time, Kuala Lumpur Aeronautical Rescue Coordination Center issued a Distress Phase (DETRESFA) message. The aircraft had been missing for five hours and eleven minutes and over four hours had past since the Distress Phase should have been declared.

By now, the Boeing 777 had been silently travelling south for four hours. It was still in the air but no one had the faintest idea where to look. Search and rescue operations headed straight for IGARI to search the South China Sea whle Malaysia Airlines flight 370 continued to fly for almost another three hours over the Indian Ocean.

The relevant parts of the of the report’s conclusion are as follows:

Evidence shows that Flight MH370 diverted from the Filed Flight Plan route. The aircraft’s transponder signal ceased for reasons that could not be established and was then no longer visible on the ATC radar display. The changes in the aircraft flight path after the aircraft passed waypoint IGARI were captured by both civilian and military radars. These changes, evidently seen as turning slightly to the right first and then to the left and flying across the Peninsular Malaysia, followed by a right turn south of Penang Island to the north-west and a subsequent (unrecorded) turn towards the Southern Indian Ocean, are difficult to attribute to anomalous system issues alone. It could not be established whether the aircraft was flown by anyone other than the pilots. Later flight simulator trials established that the turn back was likely made while the aircraft was under manual control and not the autopilot.

Note: KL ATSC is Kuala Lumpur Air Traffic Services Centre and HCM ACC is Ho Chi Minh Area Control Centre.

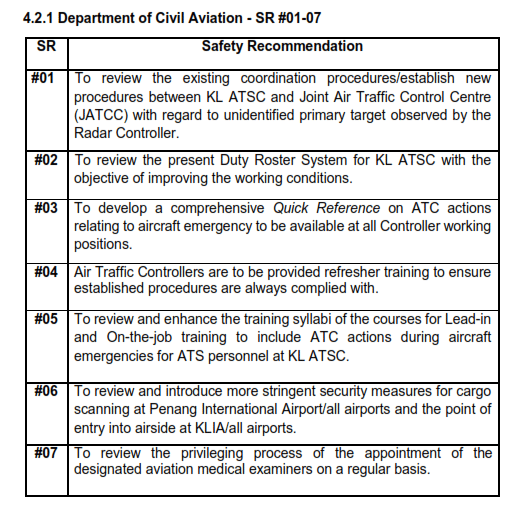

KL ATSC operation was normal with no significant observation until the handover to Viet Nam ATC. Being the accepting unit, HCM ACC did not notify the transferring unit (KL ATSC) when two-way communication was not established with MH370 within five minutes of the estimated time of the transfer of control point (Establishment of Communications, page 11 of Operational LOA between DCA Malaysia and Vietnam Air Traffic Management effective 1 November 2001). Likewise, KL ATSC should have taken action to contact HCM ACC, instead, relied on position information of the aircraft provided by MAS Flight Operations. By this time, the aircraft had left the range of radars visible to the KL ATSC. It is noted that about one minute elapsed from the last transmission from MH370 and the SSR being lost from the radar display. The Air Traffic Controllers of both Centres did not initiate the various emergency phases as required then, thereby delaying the activation of the alerting and Search and Rescue operations.

The day after the report went public, Malaysia’s civil aviation chief resigned, taking responsibility for the shortcomings of the Kuala Lumpur air traffic control centre.

There is obviously a lot more to the Malaysian safety report and also a lot more to their conclusion than the key subjects I have chosen to focus on. But these details are a big step towards explaining how this happened: how we could possibly lose a Boeing 777 in this modern age of global communications and radar coverage.

But it isn’t just a question of how. The report’s conclusions also help us to narrow down the possibilities of what happened to Malaysia Airlines flight 370. The details of the initial manual turn is extremely important, because it tells us that the Boeing 777 could not have been controlled from the outside (as per the Remote Control Boeing and Hacked Autopilot theories) because the systems in place would not have been capable of making the 35° steep turn.

Someone in the cockpit of the aircraft made the decision to turn the flight around. That is a truly important piece of information.

A second more nebulous point is the sequence of mistakes made by the controllers, the duty supervisor and the Malaysia Airlines Operations Despatch Centre could not possibly have been predicted. That is to say, it seems unlikely that someone would plan an operation which had Malaysia Airlines flight 370 going dark directly before diverting, with a goal of flying to the Indian Ocean. Under normal circumstances, the alarm would have been raised within an hour at most of the initial loss of contact, which would not have given the aircraft enough time to complete its disappearing act.

That’s not to say that the there was no malicious interference with the flight, either by the flight crew or by an outsider. However, it is hard to believe that a plot was formed which relied on no one taking any action for over five hours.

I’ll write more about the final report next week, including the flight crew profile and the cargo consignments, both of which had been largely unaddressed three years ago when I wrote my book, as well as a quick look at the wreckage which has been recovered and what it might tell us.

EDIT: This is now available here: MH370 Report: Additional Factors and No Answers

You can also download a copy of the full safety investigation report.

If you have found this post interesting, then I think you would like my book Without a Trace, a collection of true stories of aircraft and passengers who disappeared into thin air. Volume one is out now, beginning just before the golden age of aviation with a manned balloon swept over the English Channel, and ending with a top-secret spy plane disappearing at the height of the cold war. Each case is laid out in rich detail and presented chronologically, highlighting the historical context, official accident reports and contemporary news surrounding each mystery.

Sounds like a dereliction of duty by the ATC operatives. To be fair to them the midnight grave yard shift is not very stimulating. However, the military ATC noted odd occurrences and am surprised that they did not raise the alarm especially as the SSR and voice failed just after waypoint INGAR. I know very little of the oriental mindset but have the relevant authorities done a thorough search of the finances of aircrew, the pax and their relatives for potential illicit gain?

Certainly they have for the crew and they have not found anything damning. I’m still working on that section of the report. :)

Which of their duties was derelict, and please cite the relevant ICAO 4444 sections? I’m also a controller. An aircraft not in communication with ATC in a procedural environment (as this was) that they knew was still airborne (as they were, which airline’s dispatchers confirmed) means continue procedural control along their last assigned route of flight and altitude (which they did) until the ETA at the destination (which they did). Starting a hunt for primaries was pointless because of the intermittent primary hits they were getting (as was in the report). What else do you suggest they should have done?

Um, are you arguing with the commenter or the report?

I think that the conclusion makes it very clear what Kuala Lumpur should have done:

1) not waited an hour before escalation

2) not accepted reassurance from MAS that the aircraft was still on its planned route when they finally followed up

I think singling out HCM in the conclusion is a bit harsh, as the controller was repeatedly on KL’s case about the missing aircraft and the questionable information received from MAS. But it is quite clear that procedures were not follow nor even correctly understood.

Seven or eight hours seems like a long time to fly a 777 without checking in with any ATC, sending distress signals, etc. Between that, the timing of the transponder dropping out, and the lack of any effort to contact HCM ACC, I’m very suspicious that whoever had control of the plane was trying to avoid contact.

Or had a broken radio.

How many separate radios does a 777 have? I’d expect more than 1….

Ron — does ATC have no responsibility for finding out whether an aircraft is in fact at its predicted position/altitude, in order to make sure that other aircraft are clear of it? Or at least responsibility to report that they can’t do this?

CHip, I think the point is that we cannot know whether the aircraft had suffered from a technical malfunction, rather than intentionally avoiding contact.

The conclusion that the initial turn from the flight path was done under manual control would appear to support the Bailey-Vance-Dawson-Hardy view that the aircraft was hijacked by the pilot.

Nor is the pilot-hijacking scenario into question by the fact that nobody could have predicted the sequence of failures by air traffic control. If the pilot planned to hijack the plane, he did everything he needed to do to carry the hijacking out successfully, and he would have done the same whether or not a Distress Phase was declared. The failures add to the mystery, but they are not essential to the scenario of a pilot hijacking.

Agreed, interference is still very much at the table. My point was only that those theories that are predicated on the idea that the aircraft *needed* to completely disappear for the plan to be successful appear now to be unlikely.

Looking forward to next weeks post. Thanks for all your work. One thing i noted from skimming through the report was how old (relatively speaking) the flight crew was ( bar the First Officer, most if not all of them was 40+).

Interesting! I hadn’t thought about that.

Just for a moment forget about the report and start thinking logically. Contemporary airplane ✈️ equipped with everything you can imagine as an achievement in avionics, electronic, technology of building the airplanes, civil and military forces equipped with modern systems for control and navigation, satellites 🛰 and all of a sudden this airplane is flying around without anyone worrying that there is no communication for an unexceptionable period of time, there is breaching of civil and military aviation laws and rules. It’s like 9/11 all over again, this time with different outcome. It looks like lots of people knew about it and nobody took any proper action. It’s deliberate negligence from the responsible companies and agencies.

P.s I am wondering, what is the statistical predictions for this kind of scenario to occur

Paul, understanding the report is why we are here.

In terms of statistical predictions: 9/11 has happened once, 17 years ago. There are something around 100,000 flights every day. The odds are not in your favour.

It seems to me that “You have attributed conditions to villainy that simply result from stupidity.”

[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hanlon%27s_razor]

I’m sorry I wasn’t clear. I didn’t mean 9/11 to happen again (this was just a comparison), I was talking about the statistics for MH 370 . Looking at the entire story you are asking yourself “What are the odds for something like this to happen in today’s world “ I am not a specialist, but in my opinion the possibilities are very very very small, unless it’s a deliberate negligence , which was controlled from a powerful group of people. Most of air crashes are “based “ on chain of events. I know it’s not that simple to fallow the “links”, but for all that time we’ve had many specialists and equipment from a different countries and at the end we’ve got the report only. Something doesn’t end up in the entire story.

In order for there to be a conspiracy, all the parties have to have something to gain that makes extraordinary behavior — and keeping mum afterward — worthwhile to them. ISTM that the odds of that are not good either, given the number of people who would have to plot this and the ease of spreading verifiable info.

The problem is, the odds are incredibly small regardless of which theory you are partial to. I can tell you that ‘aircraft hacked from afar and taken off course’ is a lot less likely than ‘malicious interference’, sure. But when you get down to ‘pilot suicide’ vs ‘3rd party hijacker’ vs ‘extreme technical malfunction’ then looking at the chain of events, the odds are very very small for *every single option*. It becomes impossible to argue in favour or against any of them, because each one requires a leap of faith for some part of the chain of events. Without more information, it becomes impossible to narrow it down.

I do not really understand how the hand-over between ATC zones works. Is it purely up to the aircraft’s crew to get in touch with the new controller? Or is there some kind of process notifying them that the a/c has signed off with previous ATC zone and should be getting in touch with the new one?

Otherwise there would be a control gap.

If there is no automatic system, and if an aircraft’s transponder does not work the controller would only know if an aircraft should have contacted them by consulting flight schedules?

Ben, I thought I answered this but now I can’t see the comment – apologies if you get this twice. The hand-over depends on the sector. In this case, the first sector belonged to Singapore FIR but was managed by Kuala Lumpur, the second sector was belonged to Ho Chi Minh ACC. When the aircraft took off, Kuala Lumpur notified Ho Chi Minh of the estimated time to IGARI (the point where control is transferred).

Between these two sectors, there’s no electronic hand-off, nor did they have any system for notifying each other (for example, KL phoning HCM to say ‘here’s the situation’). But HCM know that at :22 the aircraft is expected to be at the transfer of control point. Normally, they would contact KL after three minutes without contact, so at :25. In this case, things were probably busy in another sector, as the controller made radar contact with the aircraft but then didn’t quite notice when it disappeared from the radar display (he noted the next waypoint on the route) and then didn’t contact KL to ask until ten minutes later. This wouldn’t have been tragic in itself, the bigger problem was that KL, who had the responsibility of dealing with the missing aircraft, didn’t appear to know it was his responsibility and spent an hour hoping to make contact rather than escalating.

If I understand correctly, the simulations show that the initial turn must have been under manual control, but subsequent course changes are ‘consistent with’ aircraft navigation systems (which I take to mean a pre-programmed course set on the autopilot). Is it reasonable to conclude from that that whoever was controlling the aircraft had the necessary expertise to (a) execute a manual sharp turn successfully, and (b) program the autopilot? That would seem to cut down the list of potential actors quite sharply (although I’m not ready to eliminate Wang Moheng just yet; babies, can’t trust ’em).

Related to that, did the aircraft specifically hit the waypoints (VAMPI, MEKAR, NILAM), or is that a ‘best fit’ of the aircraft’s actual flightpath to the known waypoints? I think what I’m asking is how far the planned route extended: at point 9 on your map, did whoever was controlling the aircraft ‘plug in’ a specific flightpath (following civilian traffic routes that seem to lie as far as possible from the coasts of any neighboring countries, and thus ground-based radars), or did they just point the nose at the Bay of Bengal and tell the aircraft “maintain course from here”?

If the aircraft was following a specific route rather than a general heading, does VAMPI-MEKAR-NILAM correspond to any part of a standard route that Malaysian Airlines aircraft might fly, i.e. Kuala Lumpur to Calcutta? That might tell us whether the person controlling the aircraft programmed specific waypoints, or just picked an existing route ‘a la carte’.

Presumably, given that subsequent searches were in the southern Indian Ocean, the aircraft must have made at least one course change — altering the heading by as much as 90° — after it was lost to radar. I assume that that too must have been either manually controlled, or pre-programmed (as opposed to a random direction change by an aircraft not being controlled either by LNAV or a pilot).

I’m mostly curious about what (if anything) the flight path might tell us about the intentions of the person(s) controlling the aircraft, and how long they remained in active control of the aircraft. (Or, conversely, how far in advance they had programmed the aircraft’s route).

” Is it reasonable to conclude from that that whoever was controlling the aircraft had the necessary expertise to (a) execute a manual sharp turn successfully, and (b) program the autopilot? ”

Point a is correct, and very important, but point b doesn’t need special novel. You could simply twiddle the heading bug to turn without programming anything. Anyone who could manage that steep turn would know this, even if they knew nothing about the Boeing 777 or its navigation systems.

There’s no way to tell to tell the difference between this and programming a specific route. Certainly the direct flight to MEKAR appears to have been intentional, but after that, it doesn’t seem that we have enough information.

Pilot Suicide, or Pilot hijacking never happened on MH370. That is because it can be proven there was no left or right AC Bus Relay supplying electrical power to the AIMS cabinets which are the navigation brains on a Boeing 777.

For confirmation of that I refer to the Australian DSTG Bayesian Analysis report dated 03 December 2015, page 6. In effect this revealed a message sent by the airline to MH370 at 18:03 UTC and repeated every two minutes until 18:43 UTC. The automated response from INMARSAT advising the message could not be delivered proved that all AC power supply (except AC Standby Bus) on MH370 was not functioning.

If power supply to the AIMS cabinets was out then MH370 could not have flown a precise course from Penang to waypoint VAMPI and then turned to intercept waypoint MEKAR.

Malaysia’s radar evidence is fake. People refuse to accept this fact and still cling to the myth of a detour west.

Your case that pilots can’t fly airplanes without advanced avionics is bunk. If you have a handheld GPS and a compass, why would it be difficult to fly a precise course? And your own quora answer at “What would happen to a Boeing 777 in the very unlikely event of a total electrical failure while in cruise?” indicates that there’s an emergency autopilot running off standby power, which I assume can keep a set heading, altitude, and speed.

Jeff Wise published a blog post on the power supply for the Satellite Data Unit (SDU) at http://jeffwise.net/2016/05/16/the-sdu-re-logon-a-small-detail-that-tells-us-so-much-about-the-fate-of-mh370/comment-page-1/ . Note that he also authored a book that came out 3 months ago that pushes the hijack theory. One of the things that preplexes him is that the SDU came back online very shortly after the plane must’ve left primary radar coverage. He writes, ” A person wanting to turn the SDU off has two options. The first is to descend into the electronics and equipment bay (E/E bay) through a hatch at the front of the first-class cabin and flip three circuit breakers located there.” To isolate the left AC bus is the other option he discusses.

So the fact that the SDU wasn’t operating doesn’t prove that the AC bus was unpowered.

(And even if it was, I don’t think it precludes the pilot flying the published radar track.)

When the radio fails to work, one can always use their transponder to sqwak their radio-out condition. But wasn’t the transponder and all identification equipment turned off as well?

Why did the loss of transponder function cause the aircraft to disappear entirely from KL ARTCC’s radar display? Shouldn’t it have remained visible to the controllers as a primary target?