MH370 Report: Additional Factors and No Answers

This is a continuation of my analysis of the Malaysian Safety Investigation Report. Last week we looked at the flight details of Malaysia Airlines flight 370, with a focus on the turn back and the response of Air Traffic Control. The detail offered in the report showed that the first turn was almost certainly flown manually, not using the autopilot, and detailed the reasons for the lack of response by Kuala Lumpur air traffic control.

Again, the report does not contain any amazing breakthroughs that would tell us why the aircraft turned back or where the wreckage is, but the investigation results can help us to look at some of the prevaling theories as more or less likely, based on the small amount of information that we have.

First, I need to dispel some myths and rumours. The first is that after the aircraft diverted, it circled Penang in what’s been described as a ‘farewell flight’. This never happened. It appeared in an article in The Weekend Australian, who wrote that the aircraft “avoided Thai military radar, then turned, after circling Zaharie’s home island of Penang.”

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau published a press release in response to the article in an attempt to stop the rumour from spreading further.

While the aircraft passed by Penang, the radar data shows that the aircraft certainly did not circle the island. The ATSB had to consider this issue, because the aircraft’s fuel consumption was an important issue in determining the search area.

There’s no reference to this ‘farewell flight’ in the radar returns. In addition, the investigative team found no evidence that the aircraft was evading radar, Thai or otherwise.

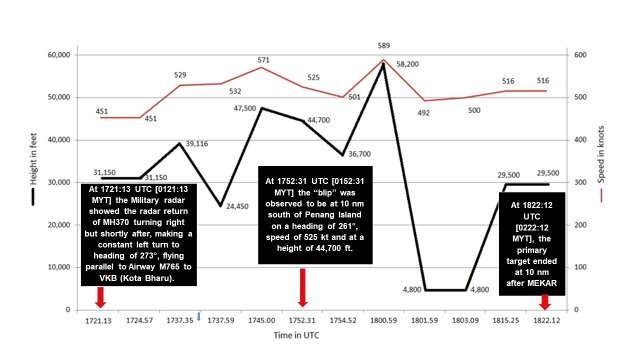

The second piece of misinformation is that the Boeing 777 climbed to over 40,000 feet with a goal of depressurising the aircraft and knocking out the passengers and crew. This stems from real data, the Malaysian military returns, which show the aircraft at a number of extreme altitudes, with a peak at 58,200 feet and a low of 4,800 feet over sea level.

However, a glance at the time stamps makes it clear that this data cannot be right. The altitude changes shows are simply not possible in a Boeing 777.

What the figures prove is that altitude returns in primary radar are not to be trusted. Air Traffic Control generally uses secondary radar, which is based on the aircraft sending information using its transponder, including altitude. The military use primary radar which does not rely on the co-operation of the target: they effectively see a reflection caused by electromagnetic waves (a form of echolocation). The disadvantage of pirmary radar is that it is limited in scope and that altitude cannot be identified directly.

Simply looking at the graph makes it clear that the altitude data collected by Malaysia’s military radar must be wrong, because a human in the cockpit of a Boeing 777 could not climb and descend at these rates even if they wanted to. It simply isn’t possible.

The Military radar data provided more extensive details of what was termed as “Air Turn Back”. It became very apparent, however, that the recorded altitude and speed change “blip” to “blip” were well beyond the capability of the aircraft. It was highlighted to the Team that the altitude and speed extracted from the data are subjected to inherent error. The only useful information obtained from the Military radar was the latitude and longitude position of the aircraft as this data is reasonably accurate.

The official report uses those radar returns for longitude and latitude, figures that primary radar can be relied upon for, and dismisses the altitude data as unreliable. Once that is done, the overlapping radar returns from various facilities are all consistent with each other.

Both of these pieces of misinformation are used to support the Pilot Suicide theory. The fact that they aren’t true doesn’t mean that the aircraft wasn’t diverted by one or both of the flight crew with malicious intent, to be sure. However, I think it is critical, especially with a tragic mystery such as this one, to stick to the facts and not justify pet theories with bad information.

The reason this is important is because the investigation could not find evidence of a technical failure or sequence of failures which fit the initial symptoms seen.

The most common theory for such a malfunction is a fire in the electronics, which could take out communication systems and overwhelm the flight crew with smoke; however, it’s hard to believe that an aircraft on fire could both not make it back to a local runway but then continue to fly straight and level on autopilot for hours.

The report concludes that the combination of the loss of communcation, the route followed and the height which the aircraft maintained does not suggest a mechanical problem.

Although it cannot be conclusively ruled out that an aircraft or system malfunction was a cause, based on the limited evidence available, it is more likely that the loss of communication (VHF and HF communications, ACARS, SATCOM and Transponder) prior to the diversion is due to the systems being manually turned off or power interrupted to them or additionally in the case of VHF and HF, not used, whether with intent or otherwise.

No issues with airworthiness were noted but, without the aircraft to inspect, it is hard to know. Many (most) accidents which have been caused by faulty maintenance were only discovered as a result of intense scrutiny of the aircraft. Without the wreckage, all we know is what people wrote down, which often does not shine light on existing issues.

The cargo on board the aircraft appears to have been a red herring. There were two items of interest when the cargo manifest was finally published: 2,500 kilos of cargo from Motorola Solutions in Penang which included Lithium Ion batteries and 4,500 kilos of fresh mangosteens.

The lithium ion batteries were not listed as dangerous goods and not reported to the flight crew, but neither did they need to be; the invesitgation found that they were packaged and transported in line with existing regulations. Motorola’s consignment contained 221 kilos of batteries and the cargo was inspected by MASkargo handlers and had gone through customs inspection and clearance. There’s no evidence that the cargo was mislabelled (as had been reported by the press at the time) or inappropriately packed. Lithium Ion batteries are commonly transported by air and in passenger flights.

The bigger issue is that, if those batteries had ignited, the resulting fire would swiftly burn out of the control, triggering alarms and warnings which would necessitate an immediate reaction from the crew. They would immediately descend to 10,000 feet and attempt to land at the first available opportunity. Based on a study conducted by TSB Canada, the average time from detection of an in-flight fire to landing, ditching or crashing is between 5 and 35 minutes. A Lithium Ion fire is even faster; it would not allow for the aircraft to continue flying until it ran out of fuel.

As to the mangosteens, I’ve never quite understood how they were meant to have caused a cargo fire but the prevailing theory appears to be that the shipment from Muar could not have been mangosteen because they were out of season there at the time, thus the 2,500 kilo consignment must have contained something else.

This accusation resulted in the investigators following the trail from farm to airport, including apparently speaking to every one involved with the shipment, including the farm labourers who picked the fruit. The mangosteen were in fact in season in Muar and Johore in March and the same company is still exporting fruit to Beijing; there was no suggestion of impropriety.

A secondary theory was that mangosteen extracts might have leaked from the packaging onto the lithium ion batteries and caused a short circuit. The cargo was all separately packaged, with the batteries in protective crates and the mangosteens in plastic containers and wrapped in a plastic sheet. Despite this, the investigators went to far as to test the effect of lithium ion batteries in contact with cardboard soaked in mangosteen juice. Nothing happened. The investigators concluded that the combination of lithium ion batteries and fresh mangosteen could only be hazardous if they were exposed to each other in extreme conditions over a long period of time, but not packaged in a cargo hold for an overnight flight.

Normally, evidence as to what the caused the crash, especially in terms of a mechanical malfunction, would be found on the wreckage but again, we have very little to go on.

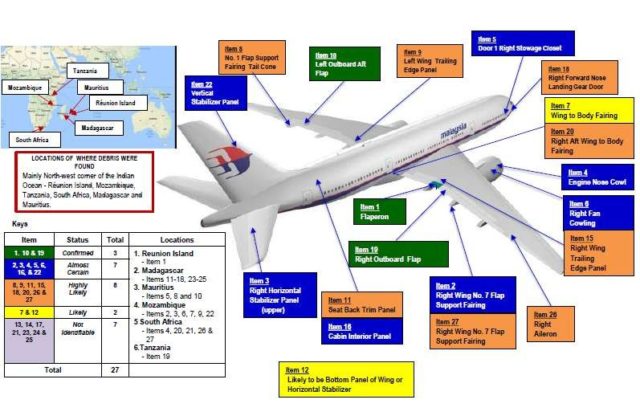

The only remains from the flight is debris which has washed ashore near or onto the south east African coast. In total, 27 items of interest has been found. Of these, only three could be confirmed as having come from Malaysia Airlines flight 370: the right flaperon, a piece of the right outboard flap and a piece of the left outboard flap. There are another seven pieces which are considered to be almost certainly from flight 370 The remaining 17 pieces are highly likely or likely, with four pieces which could not be identified at all.

There’s one piece of information about the debris which is counter to earlier reports. The right outboard flap was most likely in the retracted position and the right flaperon was probably at or close to the neutral position (that is, aligned with the flap) when they separated from the wing. This is based on the damage to both pieces and how they broke apart, which couldn’t be properly analysed until the flap was found, which was some time after the flaperon. The important point here is that the aircraft was not configured for ditching (landing on the water), it was still set up for cruise flight.

This debunks the theory that the aircraft was under control at the end of the flight and configured for the longest glide, for example in order to ensure the aircraft travelled as far from possible from the search site. The theory was always a bit shakey, since it relied on the idea that the perpetrators would know how the aircraft crash location would be narrowed down, a virtual impossibility at the time, as no aircraft had ever been tracked in that way before.

Another point to consider is that none of the 27 pieces, whether ‘likely’ or ‘confirmed’, showed any traces of explosion.

This leads us to the strongest argument in favour of crew interference: a technical malfunction or an outside plot should normally leave a trail for the investigation to follow. That’s to say, the lack of evidence for the other theories strengthen the case for this one, especially as no one has claimed credit for or any knowledge of the diversion and crash of Malaysia Airlines flight 370.

However, the evidence one would expect to find in the case of pilot suicide is missing too. Detailed investigations were made into the history of the captain and the first officer, as they were in the best position to maliciously divert the aircraft and, more importantly, they knew how to fly the plane. Either one of them would have been capable of single-handedly flying the steep turn that first took the Boeing 777 away from its planned routing.

But there’s nothing to explain why the flight crew would have done this.

Both pilots had records at the Malaysia Airline medical centre as well as at private clinics, but all treatments were for minor ailments, such as cold and flu. There was no record of psychiatric treatment.

Both were within duty-time limits and, as far as investigators could recreate, both were adequately rested.

The captain had a flawless safety record and a smooth career track to his position of Type Rating Examiner on the Boeing 777. He was well respected. The first officer’s safety record was good and he had recently been promoted to Co-pilot Under Training on the Boeing 777-200ER. There was no evidence of conflicts or problems between the captain and the first officer. This was the first officer’s last Line Training Flight before his check ride on the B777; he had just completed his upgraded training to the Boeing 777.

Investigators (and police) were searching for any signs of social isolation, change in habits or interest, self-neglect or involvement in drug or alcohol abuse through interviews with friends, family, doctors, neighbours, co-workers and acquaintances. But neither flight crew member had experienced any recent changes or difficulties in their personal relationships. There were no career related incidents or any major disciplinary records for either of them. Neither had any evidence of financial stresses or evidence of unusual financial transactions, including recent or additional insurance cover. Credit card transactions did not reveal any pattern of purchasing drugs. The captain held investment and trading accunts but they were mainly inactive or dormant, certainly no signs of major losses.

The investigation also analysed CCTV videos of the crew. Their actions from arrival at the airport to boarding the aircraft were compared to recordings from previous flights out of Kuala Lumpur but there was no sign of anything different or any manifestations of nervousness.

As the Cockpit Voice Recorder has never been recovered, the only recordings we have of the crew in the flight are the Air Traffic Control recordings. The first officer spoke on the radio until take-off, when presumably he took over as Pilot Flying, as the captain dealt with the radio calls from then until the last call. Analysis of the recordings showed no evidence of stress or anxiety. The captain repeated himself twice (saying ‘maintaining flight level three five zero’, which radar recordings show is what the aircraft did) but the team couldn’t find any special significance of this. The final good night call did not include the frequency readback, which the captain made for the previous two frequency changes, but again, it’s hard to know if that was caused by a minor distraction or just plain laziness. The controller at the time certainly didn’t find it remarkable.

The cabin crew were also investigated. Again nothing suspicious turned up. There was no record of anyone on the cabin crew having ever received any sort of flight training. No one reported any evidence of difficulties in personal relationships for any of the crew.

Now, again, that’s not to say there were no human factors or that a plot, if there was one, couldn’t have been conducted by a crew member or crew members of the aircraft. But neither is there any evidence, at this stage, that anyone at Malaysia Airlines might have been a part of a plot.

That leaves us with no evidence of an outside plot and no explanation for aircraft malfunctions that would both kill all communication and allow the aircraft to continue flying on the autopilot for seven hours and finally no sign of any trouble or reason for a crew member to have attempted to crash the plane.

This is what I was trying to explain (perhaps badly) in the comments: every possible theory is so full of holes, the odds of them happening in this way are vanishingly small. And yet, there must be an explanation.

Just as with Pilot Suicide and Third Party Hijack, the lack of evidence or strong theory for the theory of Technical Failure again doesn’t mean it didn’t happen, just that we don’t have enough information. So, I’m disappointed to see that Boeing have jumped at the chance to absolve themselves from pending court cases by the next of kin.

Boeing, in Bid to Dismiss Suits, Says Final Report Over Malaysia Air Flight 370 Found No Defect

“Given the known actions and status of the aircraft in its flight, the investigators could posit no plausible defect or system failure that would have the aircraft operating as it did,” wrote attorney Mack Shultz of Seattle’s Perkins Coie for Boeing. “Conversely, the investigators concluded that key portions of the event could only result from human input. The report also notes actions by third parties, such as the air traffic controllers, that significantly impacted the ability to locate the aircraft.”

The core facts uncovered by the investigation are all to do with how Malaysia Airlines flight 370 could have disappeared and shed no light on what happened on board the Boeing 777. The examples of lack of care and attention are all to do with the aftermath and the search and rescue for the last hours of the flight and the first weeks after the crash.

The Flight Data Recorder and the Underwater Locator Beacon was replaced in February 2008. The installation records showed that the expiry date for the battery was December 2012. This is clearly logged on the maintenance logs but there’s no record showing it was replaced.

The expiration date for the battery in the Cockpit Voice Recorder’s underwater beacon was June 2014, and the battery was replaced at that time. However, the Underwater Locator Beacon for the Flight Data Recorder still was not: the new installation of the FDR and its beacon had been logged incorrectly and as a result, the action to replace the battery was never triggered. No one noticed until after the aircraft had disappeared, when Malaysia Airline was asked for the details of the Underwater Locator Beacons.

The aircraft also had four Emergency Locator Transmitters, all of which showed as meeting regulatory requirements and with up-to-date batteries. However, ELTs are notorious for not activating when submerged. A review of 173 accidents involving aircraft fitted with Emergency Locator Beacons found that only in 39 cases were the ELTs activated effectively.

Again, this doesn’t help us to understand what happened or why, but it does underscore why the aircraft wreckage has eluded us so far.

More importantly, this single point gives us a clear area of aviation safety which can be improved. One solution to cover both the ELT and the ULB is the Automatic Deployable Flight Recorder, a technology which is already in use on military aircraft.

Following the disappearance of MH370 and in line with Global Aeronautical Distress and Safety System (GADSS) recommendation an amendment to ICAO Annex 6, Part 1 has been proposed for an Automatic Deployable Flight Recorder (ADFR). The ADFR is a combination recorder fitted into a crash-protected container that would deploy from an aircraft during significant deformation of the aircraft in an accident scenario. Considering the design and deployment features of a deployable recorder, the recorder is usually fitted externally, flush with the outer skin towards the tail of the aircraft. To find a deployed ADFR, an Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT) is integrated in the ADFR. This ELT has the added advantage to assist in locating the accident site and facilitate search and rescue efforts. In the case of a new generation ELT being fitted, the ELT will provide emergency tracking data before the impact. Furthermore, if the wreckage becomes submerged in water, the traditional ELT signal will be undetectable, but with the deployable recorder being floatable, the ELT signal would still be detectable, and the deployable recorder would be recovered quicker. As the ADFR is floatable, there is no requirement for an underwater locating device.

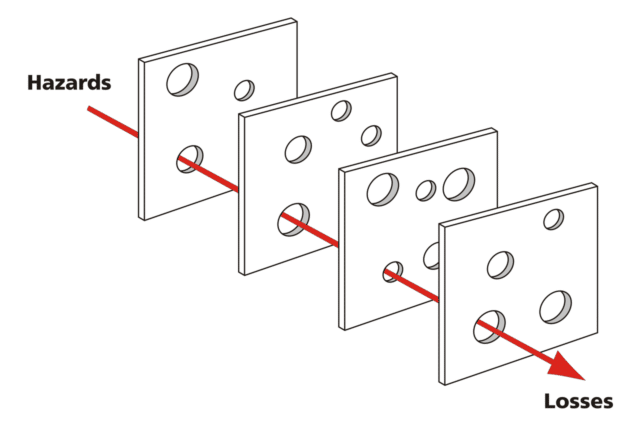

In terms of risk management, there’s a theory called the Swiss Cheese model. This image from Wikipedia does a good job of summarising it:

Each ‘slice’ of cheese is a layer of protection, that is, systems or procedures meant to deal with specific issues. The slices always have holes: humans make mistakes, procedures break down, systems malfunction. A typical accident in a modern aircraft is not simply caused by any one of these things but by a sequence of failures. The common phrasing for this is ‘when the holes line up’, which means that multiple layers of protection are bypassed by small issues which on their own would not have caused an issue, but together allow for the perfect storm.

There is, of course, much more detail in the report and I have only managed to scratch at the surface. It was clear that the investigation could not solve the mystery of what happened to Malaysia Airlines flight 370. I know that the next of kin are particularly frustrated at the fact that the search is not continuing and that the authorities have not given them any answers, and I feel for them.

But overall, my opinion is that the investigators worked hard with what they had and were up front with what they could and could not prove. The main failing of the media, at this point, is to take negative statements such as ‘there is no evidence of a mechanical failure’ and take that to mean ‘there was no mechanical failure’ which cannot be confidently stated with the small amount of evidence that we have.

Although the Malaysian aviation authority does not have a lot of experience with aviation accidents and reporting, they have followed the ICAO guidelines and, in my opinion, have done what they could with the information that they had. In addition, the following agencies have read and signed off the report:

- United Kingdom Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB)

- Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB)

- Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses pour la Sécurité de l’Aviation civile (BEA) of France

- Civil Aviation Administration of the People’s Republic of China (CAAC)

- National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) of United States of America

- Transport Safety Investigation Bureau (TSIB) of Singapore

- The National Transportation Safety Committee (NTSC) of Indonesia

All of these agencies provided advisors and support and almost all of them made comments on the draft report which were incorporated into the final version. If the report were as bad or prejudiced as some are claiming, I find it difficult to believe that not a single one of these agencies would have flagged it.

The report is available online in PDF format: Malaysian Safety Investigation Report and the appendices.

I’m looking forward to discussion in the comments but please remember to be courteous and accomodating to each other (and to me!).

I have one suggestion, and it’s an uninformed hypothesis, on why the wreckage wasn’t found, involving hydrodynamics.

It seems to me that if the 777 struck the water gently enough to mostly maintain its structure, then sank, it could ‘glide’ quite a long way underwater, with the movement of water over the wings analogous to air, just much more slowly. How far could it go before finally coming to rest at the bottom of the ocean?

I don’t know if anyone’s done hydrodynamic testing on an intact 777 moving through water.

Not that it helps much, just making the search area that much larger.

I’m also making a huge number of assumptions (structure survived impact, stable in underwater ‘glide’, heavier than water, and a lot more). Some of the ‘found’ pieces could have been torn off at impact, others floated back up from the eventual resting place.

I just hadn’t heard about this as a possibility for where the ‘wreckage’ went. Feel free to tell me I’m wrong, and why. Thanks. J.

Given the very considerable uncertainty about the location of the crash, although this idea has plenty to recommend it, would it have made the search any more difficult? Given the lack of knowledge of the ocean floor, and its extreme depth, it seems unlikely to have had much practical effect.

Did they cover other depressurisation scenarios? Christine Negroni (a respected aviation journalist and author) has found problems with the pilot oxygen masks to be plausible, as they have happened before on this model, and this specific aircraft. The scenario is along the lines of losing cabin pressure (for unknown reasons) and then the crew having problems with their masks leading to poor responses under hypoxia before passing out.

I’m also hoping for an article about the results of all this. It looks like the aviation industry is quite a bit safer as a result, sadly at this cost.

Sylvia has made quite a analysis of the details concerning the mystery of flight MH370 . I am convinced that she would make an excellent accident investigator.

See her current posting. All very logical. She deals with all that is known – and made public – in an exemplary fashion. Debunking for instance the wild, extreme altitudes that are claimed. A 777 can NOT reach 58.000 feet, absolutely impossible.

The comments, well intended, do not make sense. An airliner, unless landed by Captain Sullenberger, does not normally survive a ditching intact. It would have required piloting skills very substantially above average. What is more likely to happen is that a wingtip, or the underslung engines, hit the water. The result would be unpredictable, the aircraft might even cartwheel. A gently passage under water until the aircraft stops a few miles from the crash scene is unlikely in the extreme. And the scenario does not suggest a calm and deliberate ditching under full control.

The movements of the aircraft – insofar known – do not suggest a loss of cabin pressure. If the pilots suffered from hypoxia it would have been more logical to assume a continuation of the flight. The automatic flight systems would have – more than likely – continued to guide the aircraft on its programmed flight plan.

And even if there had been a problem with the pressurization, there are cockpit warnings alerting the crew if the cabin pressure drops (cabin “climbs”) below the equivalent of 10.500 feet.

I have not seen anything in Sylvia’s analysis that supports this.

Rudy, the hypoxia theory is based on the idea that the initial manoeuvres were made by hypoxic flight crew, thus we cannot make sense of them. After the turn to the south, the pilots lost conciousness and the aircraft continued on the last course programmed in.

Jon — aircraft aren’t nearly as dense as water. Googling “777 gross weight” gets figures of 298-352 tonnes; googling “sea water density gets 1.029 tonnes per cubic meter. Per Wikipedia, the larger 777s are just short of 80 meters long, a cylinder of sea water that length and weight would have a cross section of 4.4 square meters, which would be a circle 2.1 meters (under 7 feet) across. That’s not even the size of a narrow-body fuselage, and a 777 is a wide-body. If the plane somehow dropped its engines (avoiding Rudy’s real-world scenario) it would skip across the water like a stone instead of submarining. And if it were dense enough to sink whole, it wouldn’t go far underwater without something to push it; water is ~800x as dense as sea-level air. And that’s assuming it stayed whole; if it sank at just above stall speed it would probably turn into many pieces oriented randomly wrt motion instead of streamlined edge forward, as the airframe isn’t designed to withstand hitting something as dense as water at any speed.

I still believe that it may have been a fire in the cockpit – like flight 111. Possibly accelerated by oxygen. Circuit breakers would have been pulled. Others would have been cooked that may explain the lack of comms, or they were simply too busy putting out the fire. Then they were overcome by the fire or maybe the flight controls didn’t work.

Sadly we will only know if another 777 suffers a similar fate and crashes in a field somewhere. This has happened before – rudder jackscrew. Cant remember the plane.