Low Altitude, High Risks: Fifteen minute flight turns fatal

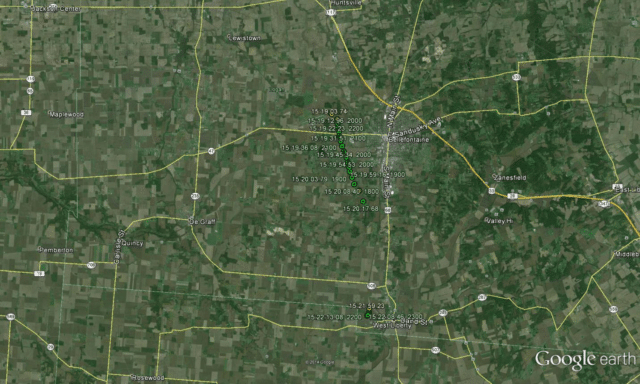

It was an overcast day on the morning of the 8th of September 2011 when people in West Liberty, Ohio, heard the sounds of a low-flying aircraft approaching. The Cirrus SR22 had left Bellefontaine, Ohio at a quarter past 11 for a short flight, just fifteen nautical miles south to Urbana, where he planned to pick up a passenger and then continue on to Jackson, Ohio.

Although the morning fog had cleared, the cloud ceiling was still just 600 feet above ground level with instrument meteorological conditions; that is, the weather conditions required pilots to fly under instrument flight rules, as the weather was not good enough for visual flight.

As the SR22 overflew Ohio, the pilot was alone in the aircraft. He had a total of 591 flight hours and was not instrument-rated.

A woman on the ground about five miles north of West Liberty heard the aircraft.

At about five miles north of West Liberty, a woman heard the aircraft. She couldn’t see it but she said it sounded like it was just above the treetops, “…too low. Way, way too low,” she said.

Soon, residents in West Liberty heard the aircraft. “[I] heard sounds like a 4-wheeler off in the distance,” said one witness. “I was sitting by the window on the north side of the house. The airplane sounded like it was very low.”

“I thought it was the grandkids with the 4-wheeler,” said another.

They heard the engine repeatedly stutter and going silent before restarting. One witness looked out the window and saw something in the sky. It was the SR22 at a 75° nose-low attitude. The witness said he didn’t even recognise it as an airplane until it crashed into the ground.

Northeast of the accident site, another witness saw the SR22 in the sky in the moments before. “The plane was performing a vertical loop when it first caught my attention. As I watched the plane incline and complete a 360° loop, I assumed it was practicing aerial acrobats. I stood to watch what would be done next and observed the plane climb into a direct vertical climb, reach its pinnacle and begin to fall tail first with a partial spin.” The witness noticed the engine go quiet and then reengage as the SR22 turned nose-first towards the ground. “I anticipated that the plane would turn horizontal to the ground at some point on its way down.”

He lost sight of the aircraft as it passed behind the trees. A muddled thud echoed. A mushroom cloud of black smoke appeared. A few minutes later, he heard the sound of sirens.

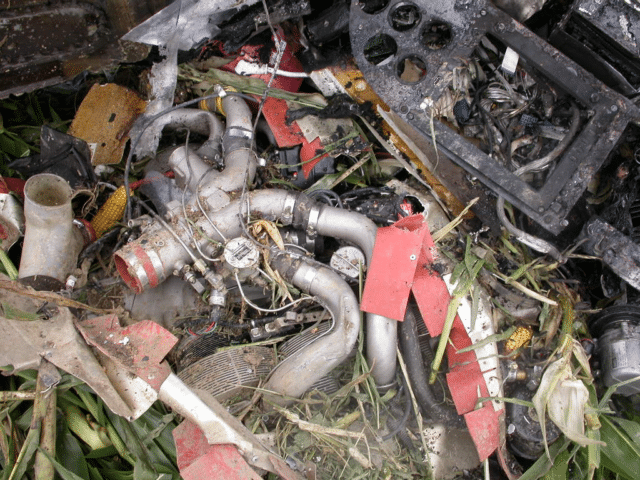

The SR22 had crashed into a cornfield about a mile west of the town. The corn was high and the battered plants showed that the aircraft was flying at 45° nose-down with the left wing low for about sixteen feet before it crashed at high speed into the ground, causing a crater which was eight feet long, six feet wide and eight inches deep. Debris was scattered around the crater. The main wreckage lay about 90 feet further in the field. A fire broke out immediately.

Although the aircraft had suffered from the impact and the fire, investigators determined that the control cables were intact. The switch for the flaps was set to flaps-up. The pitch trim motor was in the neutral position. The rocket motor for the parachute system was about 43 feet from the crater with the propellant expended. The parachute lay, still mostly packed, a few feet further away.

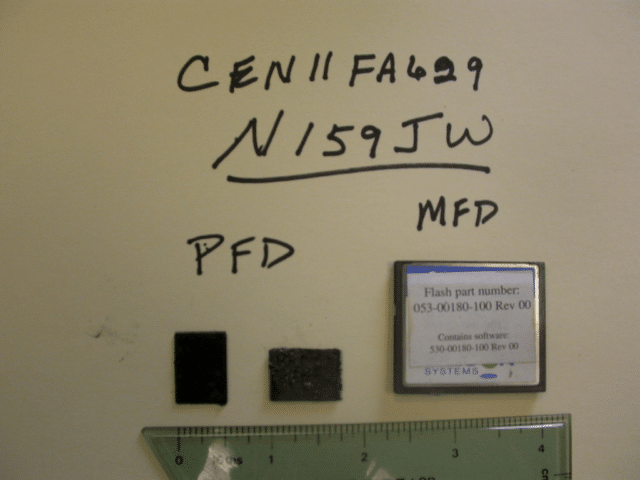

The data card from the Primary Flight Display was destroyed in the fire. The data card from the the Multi-Function Display was found in good condition and investigators were able to download the data. They found 125 files including the seven minutes of data which comprised the accident flight.

The MFD data showed that the SR22 started to taxi for take-off at 11:15 with the take-off roll starting at 11:17. After departure, the SR22 turned left towards Urbana. The engine parameters were normal and operating in normal range until the last ten seconds of the flight, when the engine RPM, the manifold air pressure and the fuel flow all suddenly dropped. This matches the description of the engine cutting out during the aerobatic manoeuvre given by the witnesses.

The pilot had purchased the aircraft used in 2006, five years before the accident. He had a total of 399 hours on type and according to his log book, he’d flown three hours in the previous four months, including a flight review the week before the accident flight.

The Cirrus SR22 is a single-engine four-seater and is currently the world’s best-selling single-engine aircraft. It is probably best known for the Cirrus Aircraft Parachute System (CAPS). Around this place, it’s mainly noted for failed aerobatics. The SR22 is not certified nor designed for aerobatic operations. For some reason, however, SR22 pilots continue to try.

Even if the pilot had been in an aircraft which was safe for aerobatics and even if the pilot had any training to fly those manoeuvres, the American FAA requires a minimum altitude of 1,500 feet above the ground. As the cloud cover was at 600 feet, the aircraft appeared to be attempting low-flying aerobatics over a built-up area, at a height where experienced pilots would be wary of straight and level flight.

Usually, in a case like this, we are left at a loss as to what the pilot may have been thinking. However, one further clue piece of relevant information was turned up during the autopsy.

An autopsy of the pilot was performed at the Montgomery County Coroner’s Office in Dayton, Ohio, on September 9, 2011. The “Cause of Death” was listed as multiple blunt force injuries. A Forensic Toxicology Fatal Accident Report was prepared by the FAA Civil Aerospace Medical Institute. The results were negative for carbon monoxide, cyanide, and ethanol. The following substances were identified in the toxicology report: 19.73 (ug/ml, ug/g) Acetaminophen detected in blood (cavity); codeine not detected in blood (cavity); 0.161 (ug/ml, ug/g) codeine detected in liver.; 0.152 (ug/ml, ug/g) diazepam detected in blood (cavity); 0.458 (ug/ml, ug/g) diazepam detected in liver; dihydrocodeine detected in blood (cavity); 0.201 (ug/ml, ug/g) dihydrocodeine detected in liver; 0.46 (ug/ml, ug/g) hydrocodone detected in liver; 0.091 (ug/ml, ug/g) hydrocodone detected in blood (cavity); 0.999 (ug/ml, ug/g) nardiazepam detected in liver; 0.21 (ug/ml, ug/g) nordiazepam detected in blood (cavity); 0.219 (ug/ml, ug/g) oxazepam detected in liver; 0.43 (ug/ml, ug/g) oxazepam detected in blood (cavity); oxycodone not detected in blood (cavity); oxycodone detected in liver; temazepam detected in liver; 0.094 (ug/ml, ug/g) temazepam detected in blood (cavity); 0.7593 (ug/ml, ug/g) tetrahydrocannabinol (marijuana) detected in heart; 6.3795 (ug/ml, ug/g) tetrahydrocannabinol detected in lung; 0.0959 (ug/ml, ug/g) tetrahydrocannabinol carboxylic acid (marijuana) detected in heart; and 0.1686 (ug/ml, ug/g) tetrahydrocannabinol carboxylic acid detected in lung.

He’d taken an amazing mix of drugs, ranging from common painkillers like Tylenol (acetaminophen) to prescription narcotics such as Valium (diazepam), Serax (oxazepam), Restoril (temazepam) to opiates including codeine, Percocet (oxycodone) and Vicodin (hydrocodone). Against all this, the marijuana in his lungs and bloodstream seems almost not worth mentioning.

When the FAA checked his records, they found that the pilot had failed to answer question 17 on his original medical history form, which asks about medications.

The NTSB final report is only nine pages long. There’s really not anything more to say.

Probable Cause and Findings

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The pilot’s improper decision to fly aerobatic maneuvers at low altitude, which resulted in a loss of control and impact with terrain. Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s impairment due to his recent use of multiple impairing drugs.

As a friend of mine put it, “And here am I getting nervous that I might have had too much coffee before a flight.”

There is no psychological report?. Although I am not a psychologist, it seems a suicide. First attempt, verticsl loop, pilot saw the ground approaching fast… and he had second thoughts about his decision. So, he tried a different approach, a vertical climb (so not to see the ground), stopped engine and irrecoverable spin

Definitely worth looking into.

I expect the engine stopped simply because it and the fuel system are not designed to operate in unusual attitudes. A witness said he heard the engine cut out 3 times, suggesting the pilot completed 2 loops, but failed to complete the third.

If the pilot had wished to not see the ground, the simplest course of action would’ve been to ascend into the cloud layer.

But the fact that the parachute system was triggered suggests that the pilot hoped to survive the accident.

I wonder if the pilot thought the SR22 was capable of doing loopings because it works in a flight simulator game?

I almost stopped reading at he “did not have an instrument rating “, thinking this was foreshadowing the inevitable outcome. But then a plot twist! And another plot twist.

It’s important to know that benzodiazepine and opiates both have complicated metabolite pathways with some forms available both as drugs and a metabolite from another drug. Oxazepam is an active metabolite formed during the breakdown of diazepam, temazepam, and nordiazepam (which is outself a metabolite of diazepam). So he might not have been taking oxazepam directly. Still, he had a sweet trifecta of substance-abuse, only missing out on heroin and cocaine.