Landing Gear Retracted: PIA flight PK8303

On the 22nd of May 2020, an Airbus A320-214 flying as Pakistan International Airline (PIA) flight 8303 crashed short of Jinnah International Airport in Karachi, killing all but two passengers on impact.

The accident is being investigated by the Pakistan Aircraft Accident Investigation Board. The investigation is led by the AAIB president and includes their own specialists in addition to two investigators from the French BEA, one investigator from the NTSB and five “co-opted members”: two A320 pilots, one doctor, one aviation psychologist and an A320 engineer. On Tuesday, the team briefed the government as to their progress and on Wednesday a preliminary report was released to give a brief overview of the process so far and the facts established in the first month of the investigation.

The report has been posted online as a PDF: ACCIDENT OF PIA FLIGHT PK8303 AIRBUS A320-214 REG NO AP-BLD CRASHED NEAR KARACHI AIRPORT ON 22-05-2020. It is a very accessible and relatively short document. I will only be covering the highlights.

Flight PK 8303 departed Allama Iqbal International Airport in Lahore at 13:05 local time for the short domestic passenger flight to Karachi. On board were two flight crew, six cabin crew and 91 passengers.

The departure and cruise were uneventful, however the preliminary assessment from the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) shows that the crew did not follow standard callouts and that they “did not observe CRM aspects (Cockpit Management Resources) during most parts of the flight.”

There are no cockpit voice excerpts in the report and a full analysis will need to wait until the CVR is released. But I think we can see pretty clearly that something went wrong during the approach phase of the flight.

Area Control Karachi East cleared the flight for the Nawabshah 2A approach procedure and advised the flight crew to expect an ILS approach for runway 25L. An ILS approach is based on the instrument landing system where the flight crew are given a specific course and glideslope to follow, which will lead them directly to the runway threshold, at which point, if everything goes well, the Pilot Flying will flare and land the aircraft.

Soon after, the aircraft was given the option to fly directly to the waypoint MAKLI with a descent to FL200. The MAKLI waypoint is around 50 miles east of the Karachi airport. They were then cleared to descend to FL50, or 5,000 feet above average mean sea level. The elevation at Karacha’s international airport is 100 feet, so height above the amsl and height above the runway are about the same.

As they drew near to the MAKLI waypoint, the aircraft changed frequencies to Karachi Approach, who cleared them to descend further, crossing MAKLI at 3,000 feet.

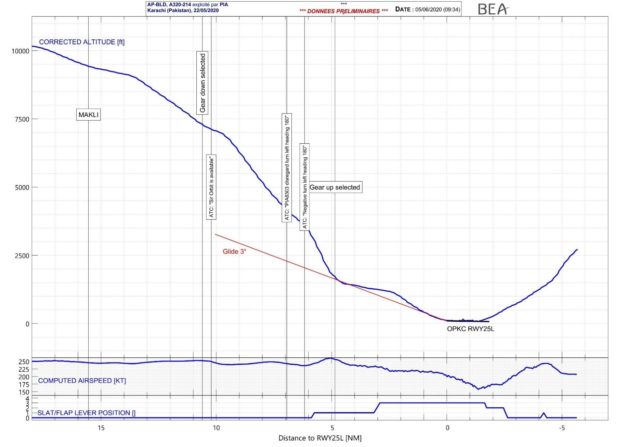

However, the aircraft did not manage to maintain this descent. As they crossed MAKLI, they weren’t at 3,000 feet, they were at 9,780 feet and travelling at about 245 knots indicated airspeed.

They attempted to lose the additional height by selecting OP DES mode on the FCU. This gets a bit weird because the report identifies this as the Fuel Control Unit but I am taking that to be an error, as the approach mode would be set on the Flight Control Unit on an Airbus. A fuel control unit controls the amount of fuel supplied to the combustion chambers which has very little to do with the approach mode.

The Airbus A320 has a managed descent mode where the flight management and guidance computer (FMGC) calculates a descent profile by working backwards from one thousand feet over runway height. The Flight Management System then uses pitch and thrust to follow that descent profile. The managed descent needs to be monitored and, if it needs adjusting, the flight crew can change to an open descent (OP DES mode). When OP DES mode is set, the managed speed target range is removed and the thrusts are set to idle. This mode would be used if, for example, ATC has required you to reduce speed to below the calculated speed of the vertical descent profile (this guide on Airbus Descent Monitoring goes into great detail). It is effectively somewhere between a managed descent and manually flying the aircraft.

The flight crew clearly selected OP DES mode in order to lose the additional height and manage the descent. At 10.5 nautical miles from the runway and a height of 7,221 feet, both autopilots were disengaged and the speed brakes were extended as well as the landing gear. The point of extending the speed brakes and the landing gear is to add drag which will slow down the aircraft during the steep descent.

Karachi Approach contacted flight PK8303 to “confirm track mile comfortable for descent”. The controller then asked if they wished to “take an orbit” in order to lose the height safely and then rejoin the descent.

The report says that Karachi Approach controller repeatedly warned the flight crew that they were too high and twice advised them to discontinue the approach. He offered them a left turn to heading 180° which I suspect was an attempt to interrupt pilot fixation and get the flight crew to reconsider the unstabilised approach.

The flight crew continued their steep descent. Flaps were set to 1 while travelling at 243 knots indicated airspeed.

I found these limit speeds (Vfe) for the Airbus A320 flaps extension in a document called A320 Limitations:

- Flaps 1 (10°): 215 knots

- Flaps 2 (15°): 200 knots

- Flaps 3 (20°): 185 knots

- Flaps full (40°): 177 knots

Overspeed warnings and ground proximity warnings began to sound in the cockpit.

At 1,740 feet, the aircraft had lost enough height to intercept the localizer — still travelling too fast but they were now able to follow the glideslope for a descent at 3°. The Flight Data Recorder (FDR) shows that at this point, five nautical miles from the runway, the speed brakes were retracted and the landing gear was raised.

Italics mine. We’ll come back to this point.

As they continued on finals for runway 25L, they would normally have changed frequency to talk to the tower, in this case Aerodrome Control, for runway information and landing clearance. However, the Karachi Approach controller opted to contact Aerodrome Control himself rather than ask the flight crew to change frequencies — to my mind, clearly worried about overloading the flight crew. The controller phoned Aerodrome Control, who confirmed that the Airbus A320 was clear to land. They would have had the aircraft in sight but they did not seem to realise that the landing gear of the Airbus A320 was not extended.

The Karachi Approach controller (who could not see the aircraft) contacted the flight to tell them that they had been cleared to land.

At three miles out, the aircraft was some 400 feet above the glideslope again, travelling at 225 knots. One of the flight crew extended the slat/flaps to the third setting, 45 knots over the maximum speed for this configuration. The FDR shows that at 500 feet above the runway height, they were descending at 2,000 feet per minute.

Neither seemed to notice the alarms sounding, perhaps because they had already decided to ignore the overspeed warnings.

The aircraft touched down. The flight crew applied reverse engine power and initiated a braking action. Neither of these did anything, as they had no weight on the wheels and no brakes to brake with. The engine nacelles scraped along the runway, sparks flying.

The controllers at Aerodrome Control must have been staring aghast as they saw the aircraft skidding along the runway at full speed. They didn’t tell the flight crew (who were not on frequency anyway, as far as I can tell) but instead relayed the information to Karachi Approach. Karachi Approach didn’t bother to contact the aircraft with this information, presumably on the basis that by now, it was obvious. Similarly, the cabin crew did not call forward to inform the captain that they were scraping the runway because how could anyone not have already known? However, there have been hints in the press briefing that ATC and cabin crew actions were found wanting, presumably because of their silence at this stressful time. I’m not sure that I agree that this is fair; however there may be more information in the final report.

I would expect, at that point, that the flight crew would be praying for the aircraft to stay on the runway and that it would stop before they ran out of runway. However, somehow, presumably assisted by their high speed on impact (I hesitate to call it a landing), they managed a go-around.

The flight data recorder shows a brief action to select the landing gear to the down position, immediately followed by moving the lever back to the up position. As they climbed away, the flight crew called that they intended an ILS approach to runway 25L. They turned into the circuit for a second attempt but, while they were in the downwind leg, the right engine failed. A moment later, the left engine also stopped producing thrust.

At this stage the Airbus A320 was going 200 knots indicated airspeed and flying at 2,700 feet.

The Ram Air Turbine (RAT) deployed to power the essential systems at which point the FDR stopped recording; it is no longer essential as there is now only limited information that it can record. The flight crew called ATC to say they were proceeding direct to the runway, by which they mean rather than fly the standard circuit.

This is where the controller asks the question that we discussed at the time: “Confirm you are carrying out belly landing?”

At this stage, the controller knew they had scraped the runway and he must presume that the landing gear had failed or collapsed as they touched down. He clearly doesn’t know that they have extended the landing gear. The flight crew’s response is unintelligible and ATC simply clears them to land on two five.

No longer able to maintain height, the flight crew declared an emergency. The controller responds by confirming that they can land on either runway, basically offering them the freedom to just get the plane down where they can.

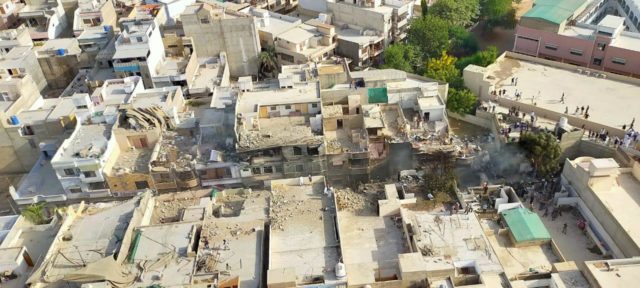

It didn’t help; the aircraft continued to lose altitude and crashed at a slow speed with a high angle of attack about 1,340 metres short of runway 25L, in the middle of a populated residential area.

The aircraft caught fire after impact. There were only two survivors on the 99 souls on board. Four people on the ground were also injured in the crash; one of those was reported to have died in hospital.

The wreckage was spread out over some 75 metres on a single street with some debris on the roof tops of adjoining houses.

The layout of the wreckage was consistent with the Airbus A320 crashing into buildings on both sides of the street at a low speed. The aircraft looked to be travelling below 150 knots indicated airspeed at the time of impact. The slats were in position 1 and the flaps were fully retracted. The landing gear was extended.

There is a “free fall” mechanism for lowering the landing gears in an emergency, which basically uses gravity to let the wheels fall into place. From what they found, the landing gear has been extended but the free fall mechanism was not used — a sign that the landing gear mechanisms were working and support for the idea that the landing gear had simply not been extended before the first attempt to land.

Both engines showed evidence of external fire. The fan blades on both engines were in good condition, which is consistent with engine being at low rotational speed at time of impact, probably not producing thrust. The right engine had clearly failed; the left engine requires further examination. This probably isn’t meaningful but please don’t let this be a case of shutting down the wrong engine in addition to everything else.

The transfer gearbox and the drain mast reservoir, both of which are located on the underneath of the engine (the engine lower part) had friction marks consistent with “scrubbing the runway”.

In a surprising break from standard crash response, local media claims that the controllers were left on duty after the crash and the airport did not immediately close the runway. Normally, the controllers would be removed from active duty immediately and interviewed while the incident was still fresh in their minds. More importantly, parts of the engine and A320 nacelle parts were recovered from the runway but allegedly after an additional two aircraft had landed.

If you want to read the original report, you’ll find the the full document in English on the CAA Pakistan website.

Although the FDR is still with the French BEA for advanced analysis, the Aviation Minister stated in his press conference that there was a clear lack of CRM in the cockpit. “In the last half hour, the pilots’ discussion was about coronavirus, they were not focused as their families were affected.”

Chatter in the cockpit is one thing but that in no way explains how either or both of the flight crew could possibly believed that this approach was worth continuing.

For me, the biggest question is why both pilots were happy to continue with this completely unstabilised approach where it was clear from waypoint MAKLI that they were in a mess. And yet, they dismissed the offer of an orbit to lose speed and ignored the request for a left turn to heading 180°, which seems to have been a clear attempt by the controller to help them lose height in a safe manner. They clearly never ran through their checklists and at the last minute, they believed that they were correctly configured for landing, despite the alerts and warnings.

The second question, however, is somehow more compelling. At five miles out and a height of 1,740 feet, why did they retract the landing gear? I can’t help trying to find logical reasons for this single action in what was undoubtedly a botched and ill-considered approach throughout. Initially, I thought that there might be a problem with the landing gear but having retracted it in an attempt to recycle the gear doesn’t fit in with continuing the flight and applying brakes as they skidded along the runway.

Here’s three theories:

- The Pilot Monitoring presumed that they were going to go around and configured the aircraft with this in mind; however he did not call a go-around or the Pilot Flying did not hear him do so.

- Once the aircraft intercepted the localiser, they no longer needed the increased drag of the speed brakes and the landing gear to slow their acceleration, so one of the flight crew instinctively retracted both, without considering the imminent landing. As they then had no time for a checklist, the fact that the landing gear had been retracted was then forgotten about.

- The Pilot Flying forgot that they had extended the landing gear and called out “gear”, meaning for it to be extended. As it was already extended, the Pilot Monitoring did the only thing he could think of and retracted the gear rather than ask for clarification.

I don’t like any of them, to be honest, but I don’t like any of the facts to do with this case either.

From the report:

The aircraft was reportedly serviceable for the said flight; necessary scrutiny of the aircraft maintenance records / documents is under way. Captain and First Officer were adequately qualified and experienced to undertake the said flight; necessary scrutiny of the aircrew records / documents is under way.

This sounds like a normal update but is thrown into sharp relief by the comments made by the Aviation Minister of Pakisan, who said in advance of a final report that he held the pilot, the cabin crew and Air Traffic Control responsible for the plane crash.

Yesterday, he added that almost 40% of pilots in Pakistan had fake licenses. In an address to Pakistan’s National Assembly, the minister said, “The inquiry which was initiated in February 2019 showed that 262 pilots did not take the exam themselves” out of a total of 860 active pilots in Pakistan. “They don’t have flying experience.”

A spokesperson for Pakistan International Airlines said that PIA has grounded 150 pilots (out of 434) with either bogus or suspicious licences. This follows an aircraft skidding off the runway in November 2018 where the pilot was discovered to have questionable credentials.

How much of this scandal relates to the crash of PIA flight 8303 is yet unknown and other than the single line regarding the scrutiny of the aircrew records and documents, the preliminary report makes no mention of this.

It’s interesting that there’s no mention of the flight experience of the crew. Usually the crew’s composition, hours and ratings are one of the first pieces of information in an aviation accident report.

So I’m guessing they don’t have much more A380 flight experience than I have… i.e. none at all.

When this comes out, it’s going to be a huge scandal.

“Weight on wheels” is a detail I missed on first reading: the thrust reversers and ground spoilers require weight on the landing gear to activate, to prevent a fatal in-air malfunction. That means with no gear, there is no way to slow the aircraft down except by grinding down the engine nacelles. If you consider how hard it is to get a freight train to stop, it’s clear that metal skidding on a hard surface is not all that good for braking.

It seems that the crew deployed the landing gear on the go-around before the engines failed. That makes sense if they did not understand why the gear was up the first time; better have the gear safely down before the landing. However, the added drag may well have been the deciding factor for the aircraft crashing short of the runway: with the gear up, they might have glided far enough to reach the airfield. Unfortunately, with the auxiliary power unit (APU) not started (they wouldn’t have had time for that), there was no way to raise the gear. All they had was a small emergency ram air turbine (RAT) that deploys automatically when the engines fail and generates just enough electricity and hydraulic pressure from the air rushing by to power the most essential systems.

I’m amazed at how neatly the aircraft body was set down on the streets. The wings and engines were shed on the rooftops, but the main body coming down between the houses meant the structures stayed intact, which probably kept many inhabitants from injury. If only the üilots had been this alert to begin with!

Mendel is right: on most types of aircraft reverse thrust cannot be deployed unless there is weight on the “squat switches”. The old DC-8 was an exception. Reverse could be used in flight to expedite a descent or slow the aircraft down. I actually have been in one when that was demonstrated.

I also agree that the gear, once extended and in the light of the damage could have made the difference between a survivable belly landing and the crash.

Sylvia gives a very clear assessment of the situation, taking into account of course the facts insofar as details have been made public.

Reading the reports and blog, I agree that there are some disturbing elements here especially regarding the highly, even extremely unprofessional way the crew handled the flight.

So were the records and / or licences of the pilots doctored?

It seems unfair to put blame on ATC. It is not uncommon for an approach controller to issue landing clearance to a crew, rather than have them change frequency to the tower. The approach controller station is, as Sylvia explained, not normally situated in the control tower and cannot see the aircraft.

The fact that they remained on duty may be due to a lack of ATC staff taking over their shift. But the failure to close the runway and failure to inspect the runway for debris definitely is a black mark.

Dear God how many of these bad-decision-makers are out there? Before any pilot is qualified to fly command in a heavy passenger aircraft, a three person “international review board” of current/retired pilots with command experience,with at least one member being from the US must interview, review and endorse his/her training and qualifications after satisfying themselves (as far as is humanly possible) that they are genuine. To pass – Flying experience and demonstrated CRM must be an essential. There are others of course, including satisfactory completion of the syllabus. If there had been such a tribunal interviewing this captain, would he have passed? Unlikely. It couldn’t be that hard to set up such tribunals and have new captains made to appear. Yes it would slow the current “churning out” process, but that might be a good thing.

John, I’m intrigued by your details of the ‘international review board’. This can’t be a world-wide requirement – to whom does it apply?

Isn’t it ironic that there is now no shortage of genuinely experienced pilots and crew all round the world, if nations check out suspect qualifications and get rid of those who don’t meet all requirements.

David

Yes David – I foresee the problems. I was just (as the Americans say) Spitballing. At least let us identify the countries/airlines that are suspect in their standards (any captain out there could name you five), check them out and get them raised. Again, who has that authority. Especially in these times where airlines are “running on an oily rag.” Dangerous days to fly, I fear.

Getting the picked countries to comply is unlikely (at best); why would they accede to such a demand? In theory the rest of the world could refuse landing rights to planes from countries designated as insufficient — but getting agreement on the designation, let alone the boycott, would be extremely difficult. (Imagine powerful country A telling small country X “We’ll veto any declaration of your insufficiency if you give us free rein for development.”) And insisting that one reviewer be from the US would kill the proposal dead — even most of Europe would probably refuse that requirement, let alone the BRICs and others.

About ten years ago or so, Pakistan International Airlines were banned from landing in the EU and probably other regions. The airline submitted proof that they had dealt with the issues (which were to do with the safety of the aircraft not the flight crew) and they were reinstated.

The countries that don’t keep up standards can end up with a blanket ban, where the aviation authority is not seen to be trustworthy at overseeing the airlines and operators under their care. In that case, all airlines from that country regulated by that authority can end up limited in their destinations or even only able to fly domestic flights.

Mendel — metal on concrete (runway composition at Jinnah, per Wikipedia) is very different from metal-on-metal. I wouldn’t have bet that an aircraft would be able to take off in those conditions, but apparently the plane and the pilots were both moving fast enough to manage it. That doesn’t mean going around was a good idea, even given how far down the runway the scraping happened (per discussion when Sylvia first posted about this crash). I don’t find whether the airport met standards for high-drag overrun areas (even after Air France 358 (Toronto, 2005) made clear that old standards were weak), although these pilots probably had no idea what overrun protection there was — they probably just panicked, thinking they’d be better off in the air than on the ground.

ISTR a discussion some threads back about systems to warn when a plane was too close to the ground without the gear extended/locked; does anyone know whether such systems are available, under development, or even being thought of?

It depends on the plane but yes, the extended ground proximity warning system was sounding an alarm as they were in a landing configuration and approaching terrain with the wheels up. However, with three or more different alarms sounding (they’d been ignoring the overspeed warning since the initial fast descent), it might have been difficult to pick out.

When they mention that many pilots have fake licenses, does that include pilots of PIA who are flying jets ?

Or does it refer mostly to private pilots who are still working their way up? Cause it does boggle the mind to think that somebody in the cockpit of a 320 doesn’t have basic qualifications, and maybe not even passed the flight exams themselves. Is that what is implied by the release of the information that many pilots are not legit here ?

Yes, Unfortunately.

The highly unstabliized approach, helpful suggestions from ATC to orbit to come around and try again, plus all the warnings blaring in the cockpit all the way down — none of them having any effect whatsoever on the pilot. Makes me think of only one thing :

Go-Around was simply not an option in his mind. Why ? Maybe he might’ve been reprimanded before for too many go-arounds, maybe his landing skills were bad. He could ill afford to have one more to go on his record with maybe his job on the line. Something big is his history is pressuring him to continue.

Something in his head ‘locked-in’ of simply having to make this landing come what may. He was ignoring the cockpit warnings as if pretending not to hear them would make those issues not exist (tunnel vision obsessed on making the landing and ignoring everything else).

The fact that the Non Flying pilot did not intercede and call a go-around is a CRM issue for sure.

But what can’t be denied is the intense internalized pressure the Pilot Flying was dealing with in order to continue this approach. I suspect the answer will be in his flying records/performance and/or psychological history.

Captain’s over confidence, co pilots subordination towards his Captain and lacking courage to correct to give his input and staying mum and agreeing to his captains decision and handling through out the landing sequence resulted in crash.

If any Captain is reading it, tell me honestly if you would allow your co pilot to disagree with you strongly or tell you sir you are not following procedures and as a co pilot, how many would report their captains irregularities to the airline or authorities responsible ? Ask yourself these questions as these are one of reasons of many crashes around that take place.

Horrible mistakes first by pilots and then ATCOs fail to see Aircraft undercarriage on finals.

What was ATC supposed to do? At the one major airport I’ve been backstage at, local control was in a ~ground-level windowless room, because managing traffic was done mostly by radar and took more people than could fit in the tower; is this atypical? Since the pilot was not on the tower frequency, nobody in the tower could have told him his landing gear was up — even if they could have seen this issue. I wouldn’t assume they could given plausible distances between tower and approach path; the smooth belly might have been visible through binoculars, but I don’t tower controllers are expected to look through binoculars at each approaching aircraft.

Some very interesting comments. For a start: I have NEVER heard of an “international review board”. Airlines, at least in Europe- and presumably also in the USA – are supervised by their civil aviation authorities. Training standards are very high. New applicants are vetted and even well-qualified pilots may not make their way through the initial training. The induction process takes months before a pilot even sees a real aircraft. Courses in company structure, rules and regulations will precede the training. Including use of the airway manuals. Many airlines use Jeppesen, British Airways used to have a system called “Airad”, KLM had (probably still have) its own system. The crew will be put through evacutation training. Larger airlines have their own simulator base where a cabin mock-up may have motion to simulate a crash. A synthesised command will tell cabin crew under training to store the trolleys (they will have been in the cabin, pretending to serve the employees who are sitting in the chairs as if they are passengers. The cabin lights will go out, the whole thing rocks and shakes and the cabin crew-under-training will have to instruct and assist “passengers” to evacuate. One side will be firm ground, with slides that can be deployed, the other side will be a swimming pool. New cockpit crew will be subjected to this as “passengers”.

Only after all this has been finished, lectures and training sessions successfully completed and certified – a CAA inspector may show up at any time during the training – will the pilots be introduced to the groundschool and simulator training for the type of aircraft they will be assigned to fly. Many pilots fail at this stage. Only after this will the “base training”, a familiarisation session on the actual aircraft take place. Every aspect of the training is recorded and kept in the pilot’s personal file. I was once during a periodic training session confronted with a record that showed that my base training had to be repeated. I was able to demonstrate that the aircraft was recalled during the training session because another aircraft in the fleet had unexpected defects and our aircraft had to be reschedeled for a line flight.

After all this, a pilot will undergo “route training” with a line training captain. An experienced F/O will be present during the first sectors as a help-out and to take over in case that the trainee cannot handle the pressure. Many already newly-qualified pilots still fail at this stage.

And a pilot, at any time in his or her career, may be confronted with a CAA inspector who cannot be refused to take the jump seat. Many are experienced and qualified captains. Is this where the “international review board” comes from?

I have some more remarks but I will leave it for the moment.

Watch this space !

My previous comment expanded on the rigorous training that serious airlines subject their crews to. No quarter given, a pilot is always on probation during his or her entire career. I know, I was an airline pilot.

During my conversion to command on the Fokker F27 I was given a final route check by the chief pilot. I had known him for many years, he had even briefly been one of my copilots on the Corvette. So when the ground staff at the airport where we landed gave him the briefing sheets – he was known as a captain, I was not (yet) – I stood back. AND was reprimanded for not behaving as the commander. Yes, even in a small cargo airline the rules are that strictly adhered to.

I always, perhaps naviely so, thought that in an airline like PIA unqualifed pilots would not stand a chance. Any experienced pilot will know within 5 minutes and without a shadow of a doubt if an applicant is properly qualified or not. His or her papers, forged or not, will not fool an interviewing panel, usually a chief pilot, fleet captain, someone from HR and / or Flight Operations Manager.

There was a movie “Catch me if you can” in which the main character dresses as an airline pilot and gets himself in the captain’s seat. The other crew members accept him and follow his “instructions”. Total cee arr ah pee: CRAP ! No knowledge of systems, checklists, performance, nothing? No chance, not even remotely believable.

So how it can be possible that pilots with dubious qualifications or experience can be accepted as captains? Only in a movie ceated by directors with extremely dubious knowledge of aviation.

Jay’s comment is referring to the same.But if the answers would have been in his records (and don’t forget so far all facts seem to point to not one but two highly dubious pilots in the same cockpit!), these answers would have been in a file kept on record for a certain prescribed time. Because in all airlines and operations that I have been employed in, both would have been EX pilots, no longer employed.

Waseem is referring to the cocpit crew cooperation and CRM. I am sure that we all know that some serious accidents have been caused because a captain did not accept input from his (seldom her) other crew members. The most (in)famous one was the on-ground collision of two B747 at Tenerife. The KLM captain, who also happened to have been the 747 fleet captain, overrode his F/O who voiced doubt s about their take-off clearance. Ever since, it is hammered into crews that they are a TEAM, each individual being trained to a supposedly high standard. So the captain is required to listen to the F/O. Who, in turn must clearly voice his/her opinion if things are not as they should.

All this, of course, does not solve the mystery of what exactly led to the crash. Certainly not how pilots who, according to what has come to light so far were very seriously underperforming, could have been accepted as flight crew into an airline.

CHip, NASA tried out metal skids on runways back in 1962 (TN-999) and found the coefficient of friction on concrete to be ~.3 and decreasing with speed (so maybe 0.25 for this airplane?). Steel skidding on steel has ~.4 (.5-.8 if not skidding), so it’s actually worse to slow a sliding plane than to slow a train, until it slides off the runway, anyway. Rubber on dry concrete slides at 0.6-0.85.

So, I’d estimate the braking action was at least three times worse than if landing normally.

From the flight data plot, the aircraft touched down at ~200 knots and slowed to ~155 knots before accelerating into the go-around. I expect 200 knots is above the maximum brake energy speed VMBE anyway: the brakes could have faded and caught fire if they had landed properly at that speed. That approach was never going to result in a good landing.

I disagree that a “review panel” would necessarily have failed the crew: we’ve seen too many instances of qualified pilots getting lax and shifting their routines toward unsafe practices. They wouldn’t be doing that on a checkride. The NTSB recommendation to catch unsafe practices is to do Flight Data Management, where someone (e.g. the chief pilot) looks at how the crews actually fly based on their FDR data (and maybe cockpit video). Typically, when an accident occurs from unsafe practices, the crew has a history of those that they got away with. I’d bet this wasn’t the first time that this crew landed high and fast.

Mendel,

I am not an engineeer, not an expert on the technical details that you obviously are able to throw into the mix. I have no idea how effective an aircraft will stop on the runway with the gear up. Never tried. I will have to take your word for it.

But I remember that Fokker in the ‘seventies did tests with the Fokker F28 “Fellowship”.

The brake test was done from an approach, landing at runway 32. This runway no longer exists, it was one of the old system before the new terminal was built. The approach was over the canal. The water in the canal is at about sea level, the runway about 11 feet (nearly 4 m.) below sea level. Coming in steeply between buildings it came to a full stop about 500 m. from the threshold. The F28 was not equipped with thrust reverse, the test pilots just jammed on full braking. The certification requires that the crew must stay on board for a certain minimum time before evacuating.

This test resulted in blown tyres and brakes on fire. That was foreseen, the fire engines were on standby. But the point I am trying to make is: the brakes are NOT supposed to fade. The wheels have plugs that release excess tyre pressure when they get too hot after an emergency braking. That is to prevent them from exploding and endangering people like emergency crew and escaping passengers. Of course, when landing with the gear retracted this all is irrelevant to the PIA crash..

Your last paragraph does not, definitely not, relate to practice in a professional airline operation. Even in small regional airlines that I worked in, the cockpit procedures were very much adhered to. Small talk, yes but not below 10.000 feet. Chief pilots or fleet captains were known for running the CVR tape at random in KLM. If the last 30 minutes revealed a lax cockpit, the crew would be called in and in some cases taken off line and put through re-training. Which would become part of their record. In years long gone, it was possible for a qualified pilot to get a cockpit seat, even in another airline. KLM had a route sharing agreement with Aer Lingus before British Airways bought them. I travelled on occasion with Aer Lingus for free. In those years the company operated B737-200. On one occasion the captain gave me the checklist and asked me to follow up in case the crew missed something. They went through the entire checklist, VERBATIM, and did not miss anything.

No, I stand by my assertion that in a professional airline, certainly in Europe, the procedures are in general very strictly adhered to and the standards are kept high.

“Review panel”: if you refer to my comment, I actually referred to a panel that determines whether a pilot will meet the standards to be hired. Which will also include a close examination of background, a medical examination to an even higher standard than the minimum for a licence renewal, as well as a psychological examination.

Captains are also interviewed at random about their (most recent) experience with the F/Os they flew with. Rostering is random. In a large, even medium-sized airline like KLM, it is quite possible for a captain and an F/O who never, or barely ever, met before to be teamed for a flight. So the likelyhood that one will agree to cover up is small enough.

When I was a captain with Ryanair the company was small: If I remember probably 10 or 12 aircraft, so we all did know one another. Often already from before Ryanair was founded. But even then, the operation was quite professional. The training captains were recruited from other airlines and they did not allow a lax standard to develop.

So, Mendel, what you describe is quite possible but my own experience points to this being the exception. Fortunately !

Air travel would not have become such a safe method of transport otherwise.

https://www.dawn.com/news/1566153/pia-banned-from-flying-to-europe-for-six-months

150 pilots have been grounded with dubious licenses. There have been other incidents like the one with the ATR listed in the article with similar piloting issues.

https://www.dawn.com/news/1565061/pia-to-ground-150-pilots-with-dubious-licences

5 of the pilots did not even graduate from high school. (Matric is 10th grade).

https://www.dawn.com/news/1454236/five-pia-pilots-have-not-even-done-matric-sc-told

In third world countries, you can’t presume you get the same level of quality/oversight in the cockpit that you get in Europe and West in general.

Jay,

Yes maybe I have been a bit naive and under the – possibly mistaken – impression that civil aviatiopn authorities worldwide cooperate and make certain that minimum standards are maintained. That may not be the case in war-torn countries where law and order has broken down, but even so…

I actually obtained my PPL in Nigeria in 1967. The Nigerian CAA was still overseen by British civil servants in those days. When I returned as the holder of a senior commercial licence 15 years later, much had changed, but the CAA which now was completely administered by local Nigerians was still run in a professional manner.

I also remember flying Nigeria Airways which operated a B707 service between Lagos and Amsterdam.

Apart from the habit of Nigerian businesswomen to bring all their merchandise with them in the cabin because they expected it to be stolen if they checked it in (maybe with good reason), the operation was professional. The Nigerian captain still maintained the old-fashioned habit of visiting the cabin, a nice touch.

But I accept that it is possible that in some countries the oversight from the aviation authorites is not what it should be. Not necessarily in the third-world, I have had an experience with a pilot who actually had been a captain with a major American airline. He had been retired, but still was flying a business jet. He broke all rules, his handling left a lot to be desired, his procedures and CRM were absent. He resembled a certain head of state who blames everything that is wrong on other people – in this case his F/O or ATC. I wondered how he had managed to survive until retirement, I was under the assumption that he had been of a generation that had long been weeded out. Obviously the professional oversight that hallmarks modern-day airline operations fails in some countries.

Mendel — thanks for the hard data; it’s fascinatingly counterintuitive, especially to anyone who has scraped themselves on concrete.

I wonder what it would take to get the data you suggest collecting. ISTM that one way would be to replace the FDR and CVR on randomly-chosen flights and look for unusual behavior, but I don’t know how easy either of those steps would be. I have the impression that they’re designed to be crashworthy rather than easily swapped out. (Wikipedia discusses a push starting decades ago for ejectable units, but apparently nothing has been done to make these happen.) Also, IIRC the tools and ability to analyze the data are not uniformly distributed. (IIRC there was discussion here of a ?French? team being called to analyze data from a recent third-world crash.) Can anyone with direct knowledge comment on either of these issues?

Mendel — thanks for the hard data; I would not have expected that reversal, given experiences on concrete, but aluminum (titanium, given NASA?) and skin are very different.

I wonder how hard it would be to get data off a CVR and FDR; I think of them as being designed to survive crashes rather than be readily accessible (for either reading in place or swapping with a new unit so the record could be read at leisure), but Rudy reports that KLM had playback access to the CVR. I wouldn’t assume it would have found anything about these pilots before this flight — it’s clear they were under stress (aside from questions about how current they were, as discussed in the previous thread on this crash) — but it would be a step. This assumes that basic data from the FDR could be read out locally; IIRC a recent thread discussed ?French? techs being called in to parse the data from a third-world crash, but finding whether parameters were exceeded at all might be easier than reconstructing exactly what happened in a crash — ISTM parameter checks could be automated. But making this happen worldwide, when AFAICT FDR checks are uncommon at best, would be non-trivial. (cf Wikipedia’s discussion of deployable recorders, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flight_recorder#Deployable_recorders; the US’s NTSB started pushing for them in 1999, but the airlines wouldn’t pay and Congress wouldn’t force the issue even with funding (legislation has been brought up periodically but not passed), so nothing has happened — even with the noise over the completely unexplained disappearance of Malysian Airlines 370 six years ago.

Rudy: I’m hardly surprised at that captain; you note he was flying a bizjet, which means there may have been nobody really supervising him. In US corporate structure he probably got an “annual review” to determine whether he got a raise, but unless the company had a large number of aircraft there wouldn’t have been a superior pilot to review him. (Not that I’d assume skills reviews even in a fleet. IIRC, you’ve mentioned flying for a branch of Digital Equipment Corporation, which for some time was big enough locally to have its own gate at Boston’s airport; what kind of supervision did you have?) And reviewers themselves may lack sharpness and/or refuse correction as you describe; there are arguments about how much each of those was a factor in the Tenerife disaster.

[[Sylvia — I thought I’d posted earlier but may have failed to press the right button. If I did and the comment is being held, please replace it with this.]]

CHip, you’re right, taking the data from the emergency FDR is cumbersome, so usually a quick access recorder (QAR) is used that records the same data the FDR does. Some aircraft even radio the data to their base while in flight.

These safety programs are actually mandated for big airlines in many parts of the world. They go by the name of Flight Data Monitoring Program (FDMP), Flight Data Analysis (FDA), or Flight Operations Quality Assurance (FOQA), which sounds less like a “big brother” thing but does essentially the same. You can read more about it at https://www.easa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/dfu/16T0153_ATR_FDM_2016.pdf .