Fatal Seaplane Crash at Oshkosh

The flight crew is often the last safety net when things go wrong, making their failures an easy target for us to point at. After all, if the pilot can be retrained or is no longer flying, then we can consider the problem solved. This allows training deficiencies, operational issues and poor maintenance to be swept under the carpet, an ongoing temptation as they are much more difficult to solve. It’s handy to have someone to blame and that is why we need to be careful not to fall into that trap.

However in general aviation cases, it’s possible for an entire sequence of events to be laid at the feet of the private pilot. This fatal crash in 2017 is one such case which appears to have been totally avoidable if the pilot had been willing to slow down and listen.

The pilot was extremely experienced: he held an airline transport pilot certificate with 33,467 flight hours, rated for single- and multi-engine land and single-engine sea planes. He was an FAA pilot examiner for over 46 years and had certified nearly 3,000 pilots. In 2013, he was inducted into the Minnesota Aviation Hall of Fame. The only black mark in his paperwork was that his medical had expired the year before. An FAA checklist of documentation required for a medical certificate was found with his paperwork, however it was incomplete and unsigned.

He was the sole pilot and owner of the accident aircraft, an Aerofab Inc. Lake LA-4-250 Renegade amphibious aircraft built in 1983, registration N1400P. The six-seater Lake Renegade set half a dozen new records for single-engine amphibians in the late 1980s, including world records for altitude, sustained flight and sustained flight at altitude. Lake Amphibious Seaplanes founders came from Republic and Grumman Corporation and claim to have developed the only single-engine, boat-hulled amphibian in production in the world today.

EAA AirVenture Oshkosh is an annual fly-in convention held every summer in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, a small town on the banks of Lake Winnebago. In 2017, it ran for ten days, from the 21st to the 30th of July. AirVenture is one of the top events for the aviation community in the US and afterwards, the Chairman said it had been incredible.

From the U.S. Navy Blue Angels and Apollo reunion, to new aviation innovations on display and two B-29s flying formation as part of 75 years of bombers on parade, it was a week filled with only-at-Oshkosh moments. You could feel the energy as thousands of airplanes arrived early and stayed longer, pushing aircraft camping to capacity for most of the event. The aviators and enthusiasts who attended were engaged, eager, and passionate, demonstrating how Oshkosh is the best example of why general aviation is so vitally important to the country. I believe it’s the best AirVenture week that I’ve ever seen.”

This video shows the seaplanes at EAA Airventure including the accident aircraft (N1400P) at the 1:10 point:

That week, over 10,000 aircraft flew in for the event and Wittman Regional Airport, the centre of the event, had 17,223 aircraft operations over the ten-day event, averaging 123 take-offs and landings per hour. The other airports hosting the event include Pioneer Airport for helicopters and airships, Ultralight Fun Fly Zone for ultralights, homebuilt rotorcraft and hot air balloons and Vette/Blust Seaplane Base on Lake Winnebago for seaplanes.

On the 27th of July 2017, the owner of the Lake Renegade decided to fly to the Vette/Blust Seaplane Base to attend AirVenture with two passengers. One of the passengers was a flight instructor with 3,000 hours flight time, with 1,600 hours instruction and 150 hours on type. He said that he had trained the pilot for seaplane flights and had personally conducted about a hundred water landings in Lake Renegade aircraft. The other passenger did not have piloting experience.

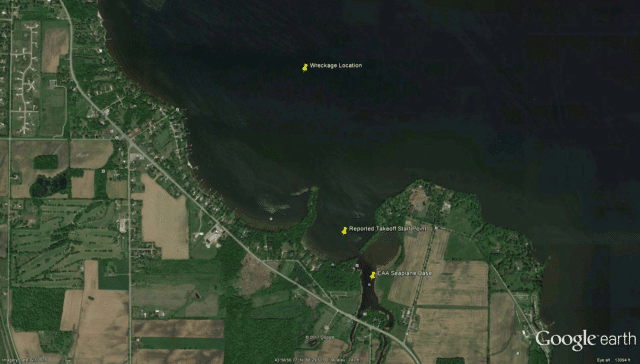

The weather that day was clear with heavy swells at Lake Winnebago. The Lake Renegade landed in a bay south of the sea base and began to taxi north along the shore towards the Seaplane Base. After a few minutes, the pilot contacted the base to say that they were taking in water and needed help.

Five boats and ten volunteers were dispatched to help the pilot but it seems like the entire base mobilised to help. The harbour master followed in his tow boat and saw the left wing was low in the water and heavy. When the Seaplane Base Chairman arrived, he saw the aircraft drifting towards shore, just 30 feet from the rocky shoreline. The volunteers manoeuvred the aircraft away from the rocks. Then a tow boat positioned itself to the right of the Lake Renegade and a passenger held down the wing in order to prevent the left wing from dipping into the lake. Like this, they were able to tow the aircraft into the Seaplane base.

The left wing sponson, a buoyancy casing that extends from the hull like a short wing in order to increase stability on water, had been taking on water after landing. They pulled the Lake Renegade’s left sponson onto the dock, where the pilot removed a plug and drained a large amount of water. Then the harbour master pulled the aircraft to a mooring plug to park.

The pilot and his two passengers left and returned about two hours later. A volunteer helping with AirVenture took the pilot to his mooring.

The volunteer boatman said that the pilot boarded the Lake Renegade and then proceeded to start the engine without untying the mooring plug first. The aircraft began to turn in a circle and the boatman stopped the pilot, asking what he was trying to do.

The pilot became argumentative, declaring “You can’t prevent me from leaving with my aircraft!”

The boatman said he that he just wanted to help and that the pilot wasn’t going to be able to leave unless he untied the aircraft from the buoy. Once the Lake Renegade was untied, the pilot asked to be towed to the ramp to drain his sponson. There, he asked for a water pump but when he was asked why — and if he had water in the aircraft hull — the pilot said no and proceeded to drain the water out of the sponson manually. He then opened the drain valve for the fuel tank in the left sponson and began draining the fuel into the water. The harbour master found a bucket and asked him to drain the fuel into that. At the same time, some of the Seabase personnel noticed that there was an inspection cover missing underneath the left wing, outboard of the sponson.

The pilot emptied the left sponson fuel tank until it ran dry, about four to five gallons of fuel. He then closed the drain and asked to leave the base.

The conditions at Lake Winnebago had deteriorated in the time that the pilot and his passengers were at Oshkosh. By now, the waves were 18 to 24 inches high (around half a metre) and the staff considered that the water conditions were too rough for the seaplane. The Lake Renegade has a maximum demonstrated wave height of 18 inches. Three pilot briefers attempted to convince the pilot that flying out would be unsafe in the heavy waves conditions. When the pilot insisted that he still wanted to leave, they called the Seaplane Base Chairman.

The chairman explained that they were concerned about the pilot’s departure because of the rough waves and convinced the pilot to join him on a boat to check the water condition in the outer bay. As they motored to the outer bay, the pilot agreed that the waves were too big and the water conditions were were unacceptable. But then, to everyone’s surprise, he said that he would simply take off parallel to the swells.

The chairman pointed out that this would mean a downwind take-off (instead of taking off into the wind to increase take-off performance). He wrote later that he told the pilot: “You will NEVER get airborne with a Lake, with full fuel, three passengers, heavy wave conditions and downwind – NEVER!”

The pilot disagreed about the direction of the wind claiming it was clearly blowing from the northwest, the opposite direction. As they returned to the protected bay of the Seaplane base, the chairman pointed out that every aircraft was pointing into the wind, showing the wind was coming from south-southeast. All of the seapbase personnel tried explain to the pilot that they were trying to help him but the pilot simply told them to take him back to his aircraft.

Once back at the base, the chairman found another Lake Renegade pilot who also agreed that the water conditions were too rough for take-off. The pilot was offered assistance in finding lodging for the night but he insisted that he was going to load his passengers and depart.

After the accident, the flight instructor, the only survivor of the crash, said that as far as he was aware, the pilot received a briefing from the dock managers and then went with the briefers for a visual look at the water conditions, where he decided it was safe. However, the observers at the sea base disagreed.

The pilot initially agreed that the water conditions were too poor; however, he later elected to depart with a tailwind despite the unsuitable water conditions and strong objections of seaplane base staff and other seaplane pilots. According to witnesses, the pilot demonstrated a strong resistance to the advice of those who he interacted with throughout the afternoon.

One of the sea base staff reminded the pilot of the missing inspection cover underneath the left wing, without which the aircraft was not airworthy. The harbour master towed the aircraft to a repair dock where they found a scrap piece of aluminium which the pilot duct taped to the hole as a temporary field repair. The harbour master recalled that the aircraft sat normally in the water, with no sign that the left sponson was still taking on water. He towed the aircraft from the dock to “the cut”, a narrow gap leading from the base to the bay. The pilot said he was going to start the engine and the harbour master held up one finger to signal that he should wait until he’d towed them into the bay. The pilot repeatedly asked to start his engine and the harbourmaster asked him to wait.

At the outer bay, the pilot started the engine the moment that the harbour master disconnected the tow ropes. He immediately applied full power for take-off.

The chairman saw the initial take-off run, which he said was with a 90° cross wind. About halfway through the take-off run, the pilot changed direction, now heading northwest with a direct tailwind. Those watching from the docks noticed with concern that the flaps were still up.

The aircraft continued to accelerate for about sixty seconds, when the aircraft bounced, beginning to “porpoise” in the high waves.

A Lake flight instructor told the investigators that a water take off with a two-foot sea state (waves at 24 inches) is unadvisable unless the pilot is very experienced. A rule of thumb taught to new pilots is to retard the throttle immediately during water take off if you feel a thump as the fuselage makes contact with the water, allowing the aircraft to settle. More experienced pilots, he said, might not retard the throttle until they felt two or even three thumps while porpoising.

The pilot did not retard the throttle. After the third porpoise, the nose rose steeply out of the water and then rolled over to the left. The left wing caught the water, spinning the aircraft by 180°. The nose dipped into the water and started to sink.

The engine remained at full power until it was submerged into the lake.

A witness told local media, “We saw the plane come out of the seaplane base, and it looked like it was having some trouble getting up. We were saying, ‘Come on little plane you can do it,’ then all of a sudden we realized it had just gone down.”

The aircraft came to rest in about 15 feet of water with the right wing partially buried in the mud. Everyone in the area rushed to the scene to attempt to offer assistance. As the first responders arrived at the crash site, they saw a man pull himself out of the aircraft and inflate his life jacket. It was the flight instructor: the pilot and the passenger were still inside.

The harbour master jumped into the water and forced open the left cabin door, where he found the pilot unresponsive. Someone passed him a knife to cut the pilot free of the seat belt and he pulled the unconscious man to the response boat, where they administered CPR. The harbour master returned to the wreck where the divers were attempting to release the passenger from the back seat. It took two of them to pull her free, and she was also taken to the response boat where CPR was begun. Both were taken to hospital in critical condition. The passenger died the following day and pilot a few days later.

The wreckage was recovered four days later for examination.

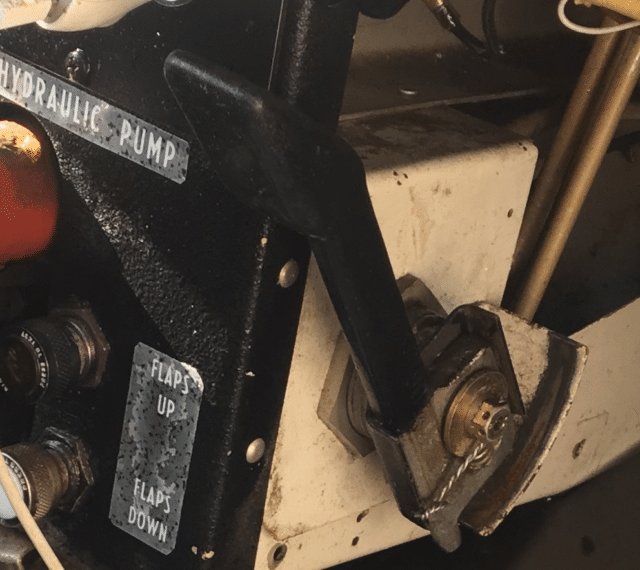

Both left and right wing spars exhibited buckling. The right wingtip was bent upward into the right aileron and the fuselage exhibited buckling deformation immediately forward of the empennage. Continuity was verified between all control surfaces and the cockpit flight controls. The landing gear handle was in the UP position and the landing gear were found retracted. The flap lever was found in the UP position and the flaps were retracted.

No preimpact anomalies were noted that would have prevented normal operation of the airplane or engine.

The flight instructor’s recollection of the chain of events seems relatively clear. He said that the pilot started a powered-up circling take-off in the bay. The plane broke water, he said, and then hit some waves. From his seat, it seemed that after bouncing about three times, the right sponson caught a wave and sucked it down, at which point the plane flipped on its side with the right wing on the water. The right door popped open on impact but by then he was underwater and it was difficult to push the door open against the water rushing in. Once he got out of the aircraft, he said he looked through the left-side window and saw an air cavity in the cockpit but, shortly after he escaped, the plane sank.

He was sure that the pilot had performed the preflight checklist before taking off. He also said that he remembered that the pilot had called out that the flaps were down (set for take-off) as a part of his checklist.

Witnesses distinctly recalled that the flaps were not down for the take-off, specifically because this seemed odd. An examination of the wreckage showed that the flap selector lever was in the UP position. And later in his statement, the flight instructor also said that in the Lake Renegade, the flaps did not have to be extended for take-off.

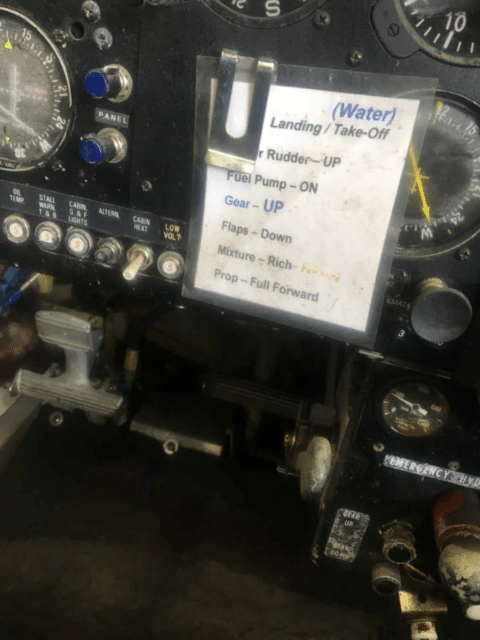

This is not true. The Airplane Flight Manual (AFM) for the Lake L-250 clearly states that flaps are used for all takeoffs and landings. Step 14 of the Before Takeoff checklist is to verify that the wing flaps are down. In the cockpit, a printed checklist was clipped to the instrument panel which also included the clear requirement to verify that flaps were set DOWN for take-off and landing.

As a result of the flight instructor’s statement, bearing in mind that he also said he trained the pilot for seaplane flight, it’s not clear whether the pilot forgot to set the flaps for take-off, simply repeating “down” out of habit as he rushed through the checklist, or if he intentionally did not set them in hopes that it would help him with the tailwind take-off over the swells.

The NTSB summarised the sequence of events:

…the circumstances of the accident are consistent with the pilot rushing to depart and failing to ensure the airplane was properly configured with flaps extended before taking off. Additionally, the pilot elected to take off with unfavorable water and wind conditions despite the advice from other pilots that he not do so. The pilot’s decision to takeoff with unfavorable water conditions and a tailwind, combined with his failure to lower the flaps for takeoff, likely contributed to the airplane stalling as soon as it became airborne and resulted in a loss of control

In other words, he never had enough airspeed or angle of attack to take off. When he attempted to force the aircraft out of the water by pulling back on the controls, the wing stalled immediately.

Probable Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be:

The pilot’s failure to properly configure the airplane for takeoff and his decision to takeoff with a

tailwind in unfavorable water conditions, which resulted in the airplane entering an aerodynamic

stall and the pilot losing control.

AOPA’s Air Safety Institute have done quite a good recreation of this crash with quotes from the witnesses, photographs from the site and the actual video taken of the take-off.

The staff and volunteers at the Airbase are all very clear that they literally begged him not to fly in these conditions. The pilot may have considered the rough conditions to be borderline and it’s true that at least one Lake pilot at the site stated that he thought it wasn’t outside of the ability of a highly experienced pilot. However, the pilot that day wasn’t highly experienced in seaplanes and he chose to risk a tailwind take-off in an aircraft that had required a tow a few hours before because it had taken on water. In his rush to leave, he either forgot or chose not to configure the aircraft correctly for take-off. It is very difficult to interpret his actions as anything other than reckless.

Any information as to why the pilot was in a rush? The narrative makes it sound like either a) he really needed to get somewhere and the urgency made him do stupid things or b) he always was this reckless and this was the day his luck ran out.

But you would think somebody with 33 thousand hours would realize getting home in time for dinner wasn’t worth the risk – unless there’s evidence his judgement was impaired as well somehow?

There are always two compass directions that are “parallel to the swells”. If one of them is downwind, then the other must be upwind. All he had to do was taxi downwind about half a mile and turn around, and he would have had twice as much room for his takeoff roll.

Just one more thing he didn’t think of, I guess.

I wondered about that as well, it’s like he did everything wrong. Flaps, downwind, either might have saved their lives. I feel most sorry for the passenger, both the pilot and the instructor screwed up, not her fault.

” And later in his statement, the flight instructor also said that in the Lake Renegade, the flaps did not have to be extended for take-off.

This is not true. ”

Sad story.

Having no experience with seaplanes, other than as a passenger (a very scary experience and a story in itself) it is difficult to make comments that make total sense. I agree with Jerry that the behaviour of the pilot is inconsistent with what can be expected from a highly experienced pilot, holder of an ATPL, and an examiner who logged 33 thousand hour-plus hours.

What is also striking is that, according to the report, he was curt to the point of being rude, even excessively so, to people who were only doing their best to help him with good advice. Advice that he choose to ignore. And so, yes, it could well be that he had been under some stress, a factor that may have caused him to make a decision that was not quite rational and ultimately led to his death, as well as that of a passenger.

I also had a terrifying experience flying in a sea plane. I’ve loved airplanes ever since I was about 6 years old. I had a best friend from grade 6 on. Her father was a doctor, a nice and intelligent man around 60 or so and he owned a Cessna 172 (or maybe it was a bit bigger) on floats. When my friend and I were just ending elementary school, he was going to take us for a short flight. My friend got in the back and I sat in the right front seat. We were strapped in and I presume he did the check lists. He began the takeoff run and just as the plane broke free of the water, his door flew open. The wind noise was very loud and sudden, and alarms blared out including the stall warning. This gave all of us quite a fright. He managed to close the door and get everything back to normal. He did not lose his composure. My friend and I were quite shaken though!

That definitely would have worried me! But I’m glad he was able to deal with it quickly and without a fuss; many accidents are caused, I think, by an overreaction to a startling event.

So true.

I had a door open on one of my flying lessons once! It gave me a bit of a fright, but my instructor was unfazed. He said something along the lines of “close it harder next time.”

The volunteer boatman said that the pilot boarded the Lake Renegade and then proceeded to start the engine without untying the mooring plug first. The aircraft began to turn in a circle…Gee What was an experienced pilot like this guy was thinking! He was cranky and displayed poor airmanship that resulted in a loss of life( I am only referring to his woman passenger)

Agreed, something is very wrong with this picture. His state of mind is something I would like to see investigated more. I feel very sorry for the passenger.

Since the pilot is deceased himself, i don’t think any Govt, agency will be bothering to investigate his mental state. I just hope that the deceased woman had life insurance for her family to move on with something, better than nothing!

Yes I was thinking about this soooo very experienced pilot forgetting to untie the plane from its mooring and not seeming to react when the aircraft started to go around in circles. That does not seem to be the behaviour one can expect from a pilot with accolades, more than 33000 hours in his log books and being an FAA examiner to boot.

What would old Sherlock have said? “Elementary, dear Watson!”

Yes, the pilot’s mindset may become part of the investigation, or it should!

It is showery here in Ireland, otherwise I would be out windsurfing.

I must not forget to untie it – ah, it is not moored, I’ll be OK.

One thing I noticed was that the missteps the pilot made were all to do with seaplane issues. His experience was with single and multi-engine land planes, so I was thinking that may have been part of the issue.

It seems that the majority of comments put the blame on the pilot. I remember have seen a billboard, I guess in New Zealand, saying “a friend does not let friends to drive drunk”. If the facts were as explained in the post, the state of mind was fuzzy if not impaired. For any reason, it may be due to a prescription or drugs, alcohol, or, sadly, to age but the pilot seemed unable to fly. But while this guy was clearly impaired, what was the Flight Instructor doing? Why did not he say that he will not board the plane?. The issue is not the position of the flaps, the issue is to start a plane while it is still tied and start doing circles (it should have been funny to see). Only this must have risen a big red flag. And if the pilot makes another mistake before taking off (like emptying the fuel in the lake) this should be enough to say NO, YOU WILL NOT FLY TODAY. By the way, the harbour master should also have stopped the pilot instead of handling him a bucket!!. A non-pilot may not have seen the seriousness of the facts that lead to the accident, but any pilot (not need to be a Flight Instructor rated in this plane) should have seen the situation and prevented the flight. Or, at least, he/she will have unboarded the plane

“The results for toxicology testing performed at the FAA Forensic Sciences Laboratory were negative for all tested- for substances.” This includes ethanol (alcohol) and various drugs.

Thanks. I should have included that; once I knew he wasn’t under the influence, I just dismissed that aspect.

A person may be unfit to flight because he is in the first phases of Alzheimer’s disease, I’ve said that he may be on drugs or his age should be taken into account. Although the post does not says his age, he had been FAA pilot examiner for 46 years. At what age did he examine his first pilot? 25 years old?. In this case, he should be at least 71 years old when he had the accident. Not everybody has Alzheimer at 71, but, probably this possibility cannot be ruled out. And you say “The only black mark in his paperwork was that his medical had expired the year before. An FAA checklist of documentation required for a medical certificate was found with his paperwork, however it was incomplete and unsigned.”. As we say in Spain, “white and in a bottle” or, as you say “it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck”

The flight instructor did not seem to see anything wrong with the conditions and appears to have been unaware that the pilot had been advised to delay his departure. I think it’s a big jump from “this pilot has made a silly mistake” to “this pilot is unfit to fly” and it isn’t clear how much the flight instructor witnessed.

His statement that flaps weren’t needed for take-off was also worrying.

Carlos,

You make a few valid points, but the pilot flying was not just an experienced pilot, but an experienced FAA examiner.

The other pilot was a flight instructor, but not nearly as experienced as the owner. But you are right, this man may also be guilty of this accident. He should indeed have questioned the owner / pilot when he started to pile up one inconsistency after the other.

From the man’s reactions to other people, it seems that the owner and PIC may well have been a formidable, forceful character.

A well known collision on the ground took place at Tenerife between two B747s, many years ago. The captain of one, operated by KLM, suffered from “gethomeitis”. He was also the 747 fleet captain. The first officer questioned the captain’s actions but was overruled. This became the worst accident in aviation history. Airlines were quick to change the cockpit hierarchy and first officers were not just encouraged, but crews were even trained to question and if necessary overrule the captain.

I have never been to Oshkosh, but I can imagine that with so many aircraft to deal with, the harbourmaster and others simply did not have time to scrutinise every crew’s proficiency. There seems to have been enough evidence to suggest that they – the ground crew – did offer advice, but they cannot really prevent a pilot from taking off unless there is strong evidence that the pilot is about to commit a violation.

A concrete example – I will of course not name the pilot involved:

A particular pilot was know to have broken aviation rules many times, but had never been caught. The authorities, in this case the Dutch RLD as the CAA is known, were keen to catch him.

One day he was taking his little twin engine aircraft for a flight. There were a few outstanding maintenance issues, the aircraft had not been released to service. But he insisted on departing, early in the morning before the maintenance base would be open.

The chief engineer found out, and obviously did not like an aircraft that was his responsibility to be flown with known defects, so he alerted the RLD.

The next morning the pilot filed a flight plan, took the aircraft out of the hanger and asked for taxi- and airway clearance. He was departing from Amsterdam-Schiphol under IFR.

The RLD alerted ATC and set a trap: they waited until the pilot accepted take-off clearance. That was the very moment when the trap was sprung. Take-off clearance was cancelled and an airport operations vehicle drove on to the runway to block him.

This, Carlos, was the only way this guy could have been caught. Even at the last minute he could have changed his mind and declare a technical problem. He violated the rules, but ONLY when he actually was about to take-off was he in breach of the law.

This trap was all planned by the authorities, and at a major international airport. All the people at Oshkosh (the nearby water base) could do was watch in horror as the drama unfolded.

There’s also this one that really shows how difficult it is to stop someone from flying their aircraft if they are adamant that they wish to continue: https://fearoflanding.com/accidents/accident-reports/unfit-to-fly/

Carlos: Sylvia cites one older report about how difficult it is to stop someone who appears incapable of flying safely in Europe. There have been recent columns suggesting this is even more difficult in the US due to attitudes about personal liberty; I recall one pilot who was massively drunk (he was stopped, IIRC partly because he couldn’t find the runway to take off on) and another who showed on the day that he was no longer capable of safe flight but wasn’t stopped as there was no legal support for anyone on the ground to do so. Some reckless drivers get stopped because there’s been so much evidence that they kill people outside their own car; reckless pilots usually (not always) have enough room that they don’t kill people outside their own aircraft. Worse: Googling “EAA AirVenture” expands to Experimental Aircraft Association, which suggests to me that there would be people actively opposed to stopping someone from flying out what they had flown in, even if they seem to be what poker players call “on the tilt”.

The passengers who arrived with the pilot did not hesitate to get back in the plane with him for the return trip, which suggests that he hadn’t previously done anything that would make them doubt his judgement. So, something must have happened on this trip that left him too angry and distracted to think clearly about what he was doing. That anger then led him to treat everyone who tried to help as an enemy.

The way he forgot to untie the mooring suggests someone who was operating on auto-pilot, falling back on habit and instinct because he wasn’t focussed on the task in hand. Since he had little experience with seaplanes, that explains why (as Sylvia points out) all his mistakes were related to the special characteristics of seaplane operations.

We’ll probably never know what got him into that state of mind, but I wonder if it started with the flooded sponson on landing. Perhaps it was humiliating for him to have everyone rushing out to help like that, especially if he assumed that they would blame it on pilot error, and from then on he just wanted to get out of there as quickly as possible.

AndrewZ I think you just hit the nail on its head.

It makes me think of the BEA Staines crash in the early ‘seventies. A BEA Trident entered a deep stall shortly after take=off and crashed, killing everyone on board.

The cause, if I remember correctly, was premature retraction of flaps and slats. No relationship with the Lake accident which is the subject of the discussion here.

But in the BEA crash, the captain had been involved in several rows with other cockpit crew members. A strike was proposed, this captain opposed it which led to quite a few disagreements, even critical non-complimentary graffiti about him was found in the cockpit.

The F/O on the day was inexperienced. In the crew lounge before departure this captain had been involved in one of those blazing rows.

His state of mind had been affected, I believe that it had been suggested that he had suffered even a minor heart attack after take-off.

In any case, this pilot was very experienced but at the time of the accident was not in a frame of mind conducive to sound decision making. The copilot’s lack of experience was also cited as a factor.

I just wonder if the pilot in the case of this Lake accident also had been in a stressful frame of mind. It can affect, and reduce, a person’s ability to make sound decisions.