Ever Left The Parking Brake On?

On the 22nd of December 2017, BMI Regional flight 1822, an Embraer ERJ-145EP (G-CKAG), was a scheduled flight from Frankfurt/Main in Germany to Bristol Airport in England. There were 22 passengers and three crew on board.

As the aircraft came in to land on Runway 27, it skidded off the runway and came to a stop in the soft ground next to the runway. The AAIB released their investigation last week and it’s an interesting case involving that embarrassing mistake that I suspect most car owners have done at least once: leaving the parking brake on.

The two flight crew consisted of a captain-under-training in the left-hand seat who was Pilot Flying and a BMI training captain in the right-hand seat, who was the commander of the flight and who took the role of Pilot Monitoring. They reported for duty at 05:40 for the flight from Bristol Airport to Frankfurt/Main and back.

The captain-under-training was new to BMI and new to the aircraft type; he had trained on a SAAB 2000 and had just 17 hours of flight time on the Embraer 145. As Pilot Flying, he planned and carried out a Category II approach and landing at Frankfurt without incident. Bristol was forecast for fog so, for the return flight, the crew again planned a Category II approach and landing. [NOTE: Please see comments below for more on this and clarifying my error and implication that the approach was planned before the flight as opposed to on approach.]

He started his approach briefing as they started their descent but, as they came into range of the ATIS broadcast for Bristol (offering current weather and runway conditions at the airport), he deferred the briefing to take in the details:

Runway 27 in use, surface damp, low visibility procedures in force, surface wind variable 3 kt, visibility 150 m, Runway Visual Range (RVR) Runway 27 400 m, fog, sky obscured, temperature 10°C, dewpoint 10°C and pressure 1035 hPa.

He resumed his briefing but was again interrupted as the flight crew received additional weather information, ATC instructions and cabin crew communications.

London ATC instructed the aircraft to descend to FL160 (16,000 feet) and reduce speed to 250 knots. The controller also told them to expect to hold for arrival at Bristol, that is, that they wouldn’t be able to route the flight in for landing immediately.

The flight crew changed frequencies to Bristol ATC. Bristol confirmed that the weather conditions were acceptable for an approach. Then, to their surprise, the controller advised them that they were number one (next) for the approach. As the Embraer descended through FL140, the controller asked if 30 track miles was sufficient distance, that is, whether they could descend and configure for landing for a more direct approach which would only cover a distance of 30 miles. The crew discussed this and agreed that they could, accepting the faster approach.

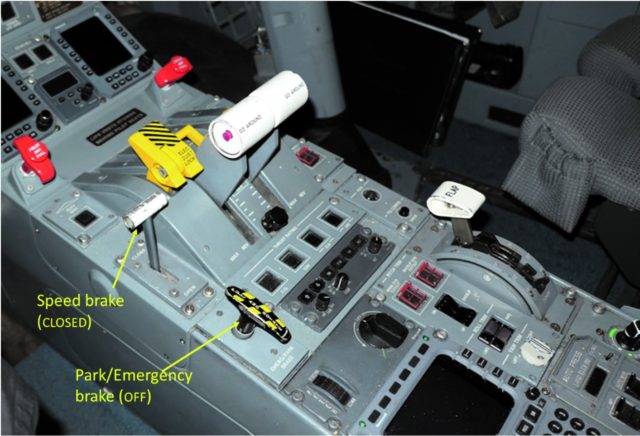

The Pilot Flying decided to deploy the speed brake to help them lose the excess height and announced “Speed brake coming on.” But according to the Flight Data Recorder, the speed brake was not deployed.

He completed the approach briefing and each pilot carried out a radio altimeter test. While they did this, the BMI training captain told the Pilot Flying that the quickest way to descend was to use speed mode and deploy the speed brake. The Pilot Flying acknowledged this and said that the speed brake was already deployed, but at that moment the training captain responded to an ATC call and didn’t seem to hear him.

After the call, the commander said outright that the speed brake needed to be deployed. “It is,” said the Pilot Flying, and then, “oh, no, it’s not. Who closed that?” He then deployed the speed brake, confirmed by the Flight Data Recorder, and asked the commander to request another five track-miles from ATC to give them some more time.

ATC routed the aircraft through the extended runway centreline to give them the extra distance before asking them to turn to intercept the ILS (Instrument Landing System) localiser from the south. The flight crew completed the descent checklist and the approach checklist was started.

The second item on the checklist read “SEATBELT SIGN ….ON”. The challenge and response system is that one person reads the item and the other person confirms the status. Instead, for some reason, the training captain read out “PARK BRAKE….” to which the Pilot Flying responded “ON.”

At the same moment, ATC instructed the flight to descend to 2,500 feet and turn right heading 360°. The crew followed the ATC instructions and then the training pilot restarted the approach checklist from the beginning, this time correctly with “SEATBELT SIGN….” in the second position, which the Pilot Flying confirmed was ON.

At 80 feet above ground level, the Pilot Flying disconnected the autopilot ready for a manual landing.

The Embraer touched down and the main wheels locked.

The nose dropped almost immediately. The aircraft verged to the right. The Pilot Flying applied opposite rudder but struggled to main control of the aircraft. The nose swung to the left, skidding along the centreline. The Pilot Flying applied right rudder but the aircraft continued to yaw to the left.

The training captain initially thought that the trainee might be “riding the brakes”, effectively applying brake pressure throughout instead of mindfully, a common error during training. He told the Pilot Flying to take his feet off the brakes.

On the Embraer ERJ145 (as well as the 135 and the 140), there is a steering tiller on the captain’s side which allows the pilot to activate the hydraulic nosewheel steering system. The Pilot Flying had been trying to use corrective rudder but as that was not allowing him to maintain directional control, he reached for the steering tiller.

The training captain saw the movement. “No, no, don’t use the nosewheel steering.”

The Pilot Flying also considered using asymmetric thrust to regain control but, later, he said that he didn’t think that he had moved the thrust levers. However, the thrust levers were advanced with slightly more left thrust than right, which was the last straw. The aircraft ran off the left side of the runway.

As the aircraft hit the grass, the training captain realised that the parking brake was on. The aircraft fishtailed left and right on the grass, continuing another 120 metres (400 feet) before coming to a halt. The Pilot Flying saw that the thrust levers had been advanced and brought them back to IDLE. Everyone took a deep breath.

(left side shown, the right side was similar)

Marks and rubber fragments on the runway defined the touchdown point, approximately 468 m from the threshold, and showed the aircraft initially tracking on the runway centreline before drifting first slightly to the right of the centreline and then veering left over 280 m.

Overheated fragments of vulcanised rubber were found at various points along the runway, with a cluster of larger fragments approximately 400 m from the touchdown point over an area of approximately 40 m by 3 m. After this point there were faint but reasonably clear lines left on the runway surface made by the wheel rims up to the point where the aircraft left the runway and continued onto the grass.

All four main wheels were buried up to their axles. But the aircraft was stopped and safe and the crew agreed that there was no need for an emergency evacuation. The Training Captain contacted ATC, saying simply, “We’re off the runway,” while the Pilot Flying made an announcement to the cabin to reassure the passengers and ask them to remain seated.

The controller activated the crash alarm and alerted the Rescue and Fire Fighting Services.

The Pilot Flying, as captain-under-training, realised that he must have set the parking brake when he originally meant to deploy the speed brake. But he still couldn’t recall having increased the thrust during the landing roll.

Investigators confirmed that the thrust levers were advanced shortly before the aircraft ran off the runway but were unable to establish if the Pilot Flying had increased them to try to maintain directional control using asymmetric thrust or whether it was a “biomechanical reaction” as the aircraft decelerated.

They also found that the parking brake indicator on the centre panel was only half lit, one of the filaments had failed.

It’s not clear from the above image; however, when the seat is in the forward position, the parking brake handle is not in the pilot’s sight, instead it is operated by feel. Embraer’s safety case had classified the severity of landing with the parking brake on as major but believed that the likelihood that it would happen was extremely improbable. But this was under the belief that it would happen due to a system fault, which had a likelihood as 1 in 109 flight hours. However, the safety case hadn’t considered the possibility of the parking brake being applied while airborne.

Embraer only knew of two other cases of landing with the parking brake set have been reported and neither was investigated as the aircraft did not depart the runway. The AAIB had also investigated a case in 2007, where the pilot had meant to select landing flap but set the parking brake on instead. All four mainwheel tyres deflated on landing but there was no further damage.

An interesting point to consider is why the training captain said “park brake” instead of “seatbelt sign” when starting the checklist. This would imply that he had the park brake on his mind, possibly having seen the illuminated parking brake indicator without taking it in. If they hadn’t been interrupted at that moment, one of the flight crew might have noticed the mistake and actually checked the brake.

Conclusion

The accident arose as a result of the inadvertent selection of the Emergency/Parking brake instead of the speed brake. The levers are of similar shape and sited close to each other but with a different appearance and mode of action. There is also a brake on indicator light. These risk controls proved ineffective in preventing the inadvertent selection of the Emergency/parking brake both on this occasion and on at least two previous occasions. Once the parking brake had been set there were opportunities to detect and correct the error, but a busy flight deck environment together with a high workload contributed to it going unnoticed.

After touchdown, the aircraft may have remained on the runway surface but for the addition of forward thrust during the landing roll.

The manufacturer stated that it did not intend to conduct a system review relating to the parking brake status.

You can read the full report on the AAIB site: AAIB investigation to EMB-145EP, G-CKAG.

The airport was closed for about 13 hours after the incident.

The aircraft was lifted out of the soft ground using a combination of hydraulic jacks and airbags so that it could be towed back to the apron. The only damage was to the landing gears and fairings.

BMI have since revised their Landing Checklist to include PARKING BRAKE ….OFF.

He who is without sin….

A training flight is always a bit stressful. A pilot who joins an airline will be confronted with a lot of new rules, regulations, new routes and what is usually called “company culture”. So there were additional stress factors: a new employer, a new type of aircraft.

Many airlines will require a new pilot to act as first officer for a certain period, even if hired as a “direct entry” captain. A recent conversion to a new type would even be a stronger ground for a pilot to fly a longer period under supervision.

There is something that I do not quite understand: Unless rules have been changed in the twelve years :-( since I had to retire from flying, there are two items that do not make sense to me.

It has to do with “cat two”.

Did the crew make an actual cat 2 approach at Frankfurt or was it practice?

A newly converted pilot can (in my time anyway) NOT be released for cat 2 unless (s)he has performed a certain number of simulated cat 2 approaches in the aircraft. They must be logged as such. And announced to ATC for the purpose. A pilot under supervision certainly would not yet be qualified to make approaches and landings under actual cat 2 conditions.

It was never allowed to PLAN a flight leading to an appproach and landing to below cat ONE minima.

In other words: When preparing the flight, weather at destination would have to conform to cat 1.

ONLY if the conditions deteriorated during the flight to cat 2 would the flight be allowed to continue. That, PROVIDED that BOTH crew members would have cat 2 training and approval.

“During the flight” meant (according to the rule book) after brake release, in other words: after the take-off roll had commenced.

Moreover, the training captain would have to have qualified as such, in other words: (s)he must have undergone simulator training for cat 2 when occupying the right-hand seat. But this is a moot point, because as I mentioned, a pilot under training will not be qualified for cat 2 yet.

So, here are a few points that I do not understand.

Judging from the article, I agree that the most probable cause was an inadvertent application of the parking brake, mistaken for the speed brake.

Obviously, misinterpretation of the warning was the reason that the crew did not notice. Workload and stress !

PS a steering tiller is common equipment on commercial aircraft. In some types it can be installed on the F/O side as well. It will be in use when taxying and during take-off until a certain speed when the rudder takes over. After landing, when the aircraft has slowed down to below a certain speed. Often, the gust lock will be applied when using the steering tiller during taxi and after landing. In turbo-prop aircraft it will also force the propellers to stay in the beta range. Naturally, it will be unlocked before take-off.

It does sound as if there was enough going on to cause difficulties on a normal flight, let alone one adding training. (And, per Rudy’s note, I’m a bit surprised that the trainee was in the left seat after so little time in type.) I also wonder whether anyone has looked at an interlock such that the major ground brakes couldn’t be applied unless there were weight on the landing gear — would that be more likely to prevent trouble, or to fail at a critical time?

Chip,

A trainee will be occupying the seat he or she will be in when released on line. Starting in the simulator. A captain undergoing training will therefore be in the left-hand seat, which has been the case for many years. In some countries, like the Netherlands, the rules do not determine separate type qualification for captains and first officers. It is the company that determines their status. In the past, KLM had a policy whereby the pilot-flying would be in the left-hand seat, but they introduced a fixed-seat policy many years ago.

So my comment is related to the fact that in most cases new entrants in a company will be eased into their new environment by flying for a period as first officer. Because, even if they flew the same type before joining, a non-pilot would be very surprised by the very many differences there can be in company regulations and -structure between operators. So, UNLESS they have a lot of time and experience in the type, or a very similar one, it is usual that they are going to operate as F/O for the first few months.

BMA obviously were short of captains. This new captain probably had a solid background in related types and/or operations to be considered ready to take over as direct entry captain from the start. Not usual, but not unheard of either.

Your second remark, Chip: Aircraft have so-called “squat switches” on the landing gear that will prevent, for instance, retraction on the ground with the aircraft weight pushing down and closing the switch.

They have various functions, depending on the design. E.g. depressurizing the aircraft if the cabin was still not fully depressurized on touch-down, de-activating the brakes until on the ground, limiting aileron control (which nearly led to an accident in severe crosswind with an A320) among other functions.

The problem that I can see is: even if the parking brake were wired into the switch, if the handle were by mistake placed in the “set” position in the air. the brake would activate instantly after the aircraft landed. De-activation would obviously defeat the purpose. Perhaps a baulk that would only allow it to come on after the gust lock would be applied? That assuming that the aircraft would taxi with the lock “on”. In that case, the aircraft would be at low speed. But that also means that the parking brake can not have the function of emergency brake. I do not know the Embraer, I am now purely speculating.

And I am not sure how to read the comments about “Cat Two”. Even if so qualified previously, a pilot under training will NOT be authorised to make Cat Two approaches under actual Cat Two weather conditions. (S)He will have to demonstrate that a number of practice approaches have been made. They must be announced to ATC and logged as such.

Because the ILS signal can be affected by the presence of large chunks of metal, being other aircraft, the separation between approaching aircraft has to be increased and the “cat 2 holding” is further away from the runway.

When doing a practice Cat 2 approach, ATC must take that into account and during busy times may decline to approve it.

Furthermore, as I mentioned, a flight may not be PLANNED as cat 2 when the destination is below cat one minima.

In the “wild west” of executive flying this can be solved by designating the destination as an alternate.

But for alternates, the weather conditions must meet even higher criteria, so at least another alternate must be available that meets the required weather increments.

Cat 2 and cat 3 approval is very difficult to obtain for private/corporate operators, so in general this trick is not really an option.

I am a retired RAF air traffic controller. The fact that the training captain called out ‘parking brake’ instead of ‘air brake’ when reading a check list and the fact that the u/t cap rain responded with ‘on’ should be worthy of comment. The response shows an automatic reply rather than physically checking the item called and then responding; furthermore, the u/t didn’t listen to what was being said otherwise he would have queried it with the trainer. I have experienced similar instances of this when controlling pilots undergoing instructor training in fixed undercarriage Bulldog a/c. These pilots would just have come off front line a/c with retractable undercarriage and would occasionally call ‘finals three greens’ when turning onto finals in the circuit, when of course there were no ‘greens’ in the Bulldog. It always made me wonder how many times responses may have been given without the physical check being made. The station flight safety officer didn’t consider it was worthy of taking any further!

Interesting comment, Roger.

The only thing that I still find strange:

Considering that the trainee was hired as a direct entry captain strongly suggests that he must have been very experienced.

And, insofar as I can hark back at my own time in the cockpit, usually a pilot under training might have been expected to be doubly cautious.

After all, according to the blog, he was a new entry with BMI and any flaw in his flying or decision making could and would have ended his employment. It was probably not even a matter of going back to the right hand seat.

The situation was possibly a bit stressful, but it did not appear to have been beyond what an experienced pilot could be expected to be able to handle.

I have been in the right-hand seat myself, as training- and check captain on Fokker F27. I usually managed to eliminate the unnecessary stress element. But that is another story.

This is a more complicated story than meets the eye.

I read that the new captain had flown SAAB 2000. A turbo-prop but known as a “hot ship”. A Swiss airline, Crossair (which has taken the mantle of former Swissair and now is called “Swiss”) operated HS 146 and because it has 4 engines nicknamed them “Jumbolino” (little Jumbo).

The called the SAAB 2000 “Concordino”. You can guess why.

So it may be assumed that this pilot was experienced and had previously flown a demanding, high performance type of aircraft.

The crew “again planned a Category II approach and landing.”

This type approach I am nearly certain may not be planned prior to departure, nor carried out by a pilot undergoing training, at least not under actual cat 2 conditions.

A cat 2 approach requires a stabilized approach path, also known as a “monitored approach”. The autopilot will do the flying, the captain will monitor and the F/O will be glued to the instruments. When approaching the minima, (for cat 2 this can be as low as 100 ft) the captain will be scanning outside and will either announce “landing, my controls” (the exact words depend on company procedures) or will call for a missed approach. The captain will take over the controls for landing. There may be procedural differences between companies, but it will be obvious that CAT II will require additional training, practice approaches are required and must be logged on a regular basis in order to remain current.

Moreover, a shortened high altitude and high speed initial approach are not compatible with Cat 2 procedure and, if lo-vis procedures were in force, the crew should not have accepted it and ATC should not have offered it in the first place. They were at about twice the normal altitude for an approach, thundering in at 250 kts if I read it correctly.

If the weather conditions met Cat 1, and the crew were planning a practice Cat 2, ATC should have been informed, and they would have taken this into account.

But: CAT 2 requires additional training which is not normally combined with initial conversion training on a new type.

As the book says: “Curioser and curioser”.

Hmm, Rudy, the planning informatjion might be my error, I had no idea that it couldn’t be planned prior to departure so I think I misunderstood what the report said. In fact, now that I’m looking, I can’t see any reference to the outbound flight being planned for Cat II.

The summary looks to me, now that you’ve clarified, that the “planning” was done on approach and not in advance.

“The outbound sector to Frankfurt was uneventful with the captain-under-training designated

as PF; a Category II approach and landing was carried out. The return sector was also

flown by the captain-under-training and a Category II approach and landing was planned

for Runway 27 at Bristol due to the meteorological forecast for fog.”

Rudy: “a non-pilot would be very surprised by the very many differences there can be in company regulations and -structure between operators.” Not any more, at least in the US; there has been significant coverage of the mess during the merger of American Airlines and USAir — one story described it as continuing to operate two parallel airlines. (BTW, I assume you mean “non-corporate pilot”.)

wrt the squat switch and the brake, my thought was that the brake could not be set until there was weight on the wheels, rather than the handle setting a trigger that would be activated by weight. But that would probably require more-complicated linkage than would be reasonable, and might risk failure in the opposite direction.

Chip,

I was referring to differences between AIRLINES. A former co-pilot of mine joined British Caledonian and flew the BAC 1-11.

BCal was taken over by British Airways. He told me that he nearly had to learn how to fly the 1-11 all over again, such were the procedural differences.

How to prevent the brake being “ON” after touch-down may not be so easy to solve, not mechanically. An additional call in the checklist would probably be the best solution.

But I stick to my own assessment:

This crew were not operating legally. Harsh words, yes.

But the whole sequence, when I re-read it, is a set-up for an accident which already started in Frankfurt.

Pilots on a training flight, where one is being checked out after conversion on a new type are NOT qualified to make Cat 2 approaches. During the planning phase, the weather at destination must conform to Cat ONE.

Moreover, a Cat 2 approach requires special training and follows a so-called “MONAP” procedure. It must be fully stabilized and the CAPTAIN is the monitoring pilot, but will take control for landing.

There is a good reason for this: (S)He will be looking outside during the last phase and therefore his/her eyes will already have been made the transition to the conditions outside. After all, that can be in fog and from 100 feet height. How does an airline solve this? If the forecast looks like Cat 2 weather minima, the training flight will be cancelled and a Cat 2 qualified crew will take over. Or: an extra Cat 2 qualified pilot will be in the aircraft. But that would require the training captain to be Cat 2, and from the way they made their initial- and final approach I strongly suspect that the training captain was totally UNfamiliar with Car 2 operations.

So: this accident started to happen when the crew planned (!!) a flight to a destination that could have been expected to be Cat 2.

They were unfamiliar with the procedure, accepted a high altitude high speed initial approach which piled up the stress level to beyond what they could safely handle. Leading to missed checklist items and an incomplete crew briefing.

In short: they knowingly busted limits.

I find this unbelievable. Was the operator really BMI or a smaller company, operating some of their flights but not to BMI standards?

Neither pilot were up to the task, but the real blame lies with the training captain. In my opinion the verdict should read:

Captain under training – employment discontinued.

Training captain: Lucky if he only were demoted to first officer.

Mind: I started my first entry with “whoever is without sin”.

I admit that I have done stupid things myself.

But I know that if I had been caught out, my career would have suffered the consequences too.

My comments are drawn only from my own memory and experience.

Sylvia,

A crew member under training is NOT qualified for Cat 2.

As I explained, it requires a very different procedure and may not be preceded by a rushed initial approach. The aircraft must make a (very) stable, settled final approach.

There is a good reason for that: the world looks very different in fairly dense fog, from a decision height of 100 ft and a visibility of about 350 meters than from 200 ft and a visibility of about 500 or 550 metres, which are the usual limits for cat one.

Repeat:

Captain: left seat, NOT pilot flying, monitors the approach and compares the instruments. Approaching minima (s)he will also include the outside in the scan and the captain will decide to continue for landing, or make a missed approach. At that moment, the captain will already have made the visual transition and will announce something like “Minima, my controls”. The CAPTAIN will then take over and land the aircraft.

First officer: will concentrate on the instruments until the captain’s annnouncement. The approach must be flown on autopilot which must conform to Cat 2 standards.

ATC will be responsible for maintaining greater separation between aircraft in the approach. Departing aircraft will hold at the “Cat 2” holding, at a greater distance from the runway to eliminate interference with the ILS signals. Cycling orange lights at the marker boards will alert crew that they have to stop there. Of course, approach- and runway lights also must conform to Cat 2 standards.

The fact that “Cat two” may NEVER be part of pre-departure planning makes no difference; this crew was not Cat 2 qualified.

This is clear even from the fact that they accepted a high speed, high altitude intial approach. Not outside the limits under normal condition, but NOT suitable for Cat 2. Especially not for a pilot with only 17 hours on type. Admitted, the training captain was the commander but a pilot being trained as a captain is expected to act as such. It is the job of the training captain to judge and guide the new trainee and if necessary correct him or her.

In this case, the trainee did not seem to act as a captain and the training captain’s input was not what it should have been either.

Neither seemed to have been aware that they had no Cat 2 clearance, they were just making it up as they went along.

The cause of the incident was self-inflicted: they engaged on a type of approach that they were not trained for nor authorised to carry out, which led to a high workload that they were unable to cope with.

So: The new captain got interrupted twice in the approach briefing; the training captain was distracted while going over procedures; they both got interrupted again just in time to hide the TC’s revealing mistake on the descent checklist; and the trainer corrected the TC for one mistake they hadn’t made and a second they had, but neither was the key mistake.

Sounds like a perfect storm of distractions!