CRJ 200 ferry flight crash with 19 on board at Kathmandu

Last week, the Aircraft Accident Investigation Commission, formed by the Government of Nepal to investigate the accident of 9N-AME on the 24th of July 2024, released their final report. There’s a lot going on here, so I hope you are seated comfortably!

New! You can also listen to an automatically generated audio file of the article!

It should have been a simple ferry flight, under 150 kilometres. The owner and operator, Saurya Airlines, is a Nepalese domestic carrier founded in 2014 with a single Bombardier CRJ 200. In 2017, they purchased a second CRJ 200, registered in Nepal as 9N-AME, as a back-up aircraft. As of July 2024, this was their only operational aircraft.

Except that it wasn’t operational. That CRJ 200LR had been grounded for 34 days .

The day before the accident, the Air Transport Division of the Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal approved the ferry flight for the aircraft to fly from Tribhuvan International Airport in Kathmandu to Pokhara International Airport, where the CRJ 200LR was to undergo base maintenance (C-check). The aircraft had already undergone preservation of aircraft and return to service maintenance checks.

That morning, the first officer was first to arrive in the cockpit, while Saurya Airlines personnel loaded the cargo. The ground staff said the cargo section was completely full, so they had to load the remaining baggage and equipment into the cabin.

Saurya Airlines was the first officer’s first employer; he had been with the airline since he’d finished his commercial training in 2021. When converting the CRJ 200, he’d failed his initial simulator check, which led to him extending his training in Germany by three months. This significantly increased his training costs, which was added to his bond with Saurya Airlines, meaning he had to remain with the airline or else pay back the remaining balance. On top of this, he had had to take out a loan to fund his living costs in Germany for the additional training.

He’d then been laid off by the airline for an unspecified time but later reinstated “based on flight hours”. His duty and flight hours were significantly reduced, as the company’s operations were low. His simulator performance was marked as Satisfactory.

While the first officer went through the pre-start checks, the flight dispatcher called with the aircraft weight and balance: 18,137 kilogrammes.

The first officer would use the aircraft weight, along with the environmental conditions and the runway parameters, to determine the V-speeds for the flight and enter them into the flight management system.

The key take-off speeds are V1, which is the speed at which a take-off should no longer be aborted, VR, the speed at which to rotate the aircraft, lifting the nose for take off, and V2, the speed at which the aircraft can still safely climb with one engine out. These speeds are calculated before every flight, marked on the airspeed with coloured bugs, and repeated as part of the pre-flight briefing.

Now that the first officer had the take-off weight of the aircraft, he could use the speedcard booklet to calculate the V-speeds for the flight.

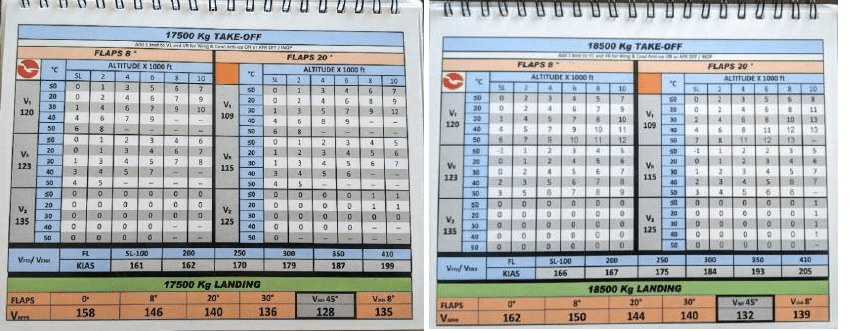

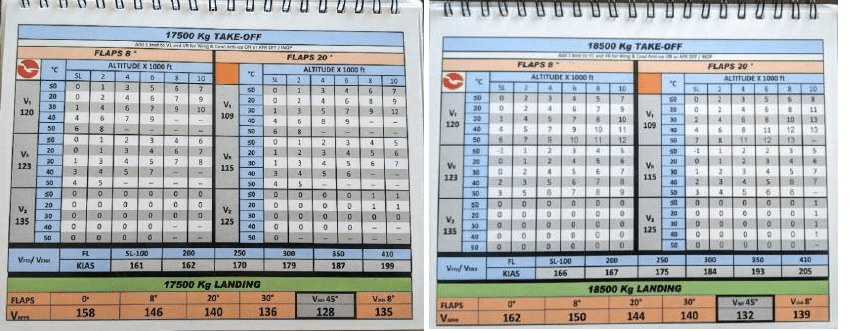

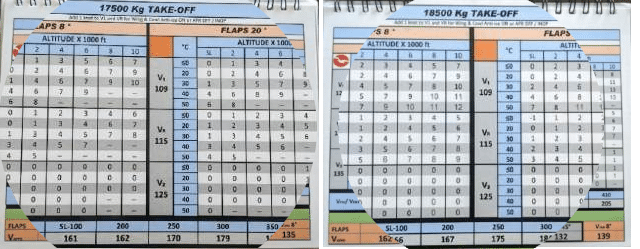

He flipped to the card for 18,500 kg take-off weight and used the base V-speeds for flaps at 20° (V1: 109, VR: 115) V2: 125) to calculate the correct speeds for the CRJ 200 based on their altitude of 4,400 feet above sea level.

- V1 (take-off decision speed): 114 knots

- VR (rotation speed): 118 knots

- V2 (take-off safety speed): 126 knots

The captain arrived at the cockpit. He had joined Saurya as a first officer in 2015 and was promoted to captain in 2017. Now he served both as a captain and as Saurya’s Operations Director. His simulator performance was marked as Excellent.

There were 30 minutes until the intended take-off. The captain asked about the checks that the first officer had done so far and provided supervisory instructions. A third crew member, an Aircraft Maintenance Technician, joined the flight crew and they discussed the C-Check planned in Pokhara and “other casual topics unrelated to the flight” with some of the staff in the cabin.

At that point, the flight crew were contacted to say that they needed to delay their departure, as more personnel were expected. The captain responded a minute later that they were going to have to cancel engine start-up. Air Traffic Control noticed the same thing, calling the crew to ask whether they needed their taxi to be delayed. The crew responded that they needed more time, up to 30 more minutes.

The remaining Saurya personnel arrived at that point and the cabin door was closed. The crew initiated start up of both engines and they began to taxi, doing the control surface checks along the way. The flaps were extended to 20°. They entered runway 02 and performed a backtrack to the threshold in order to use the full length of the runway.

At exactly 11:10 local time, the crew called from runway 02 that they were ready for departure.

At 11:10:25 they applied power for take off with both engines N1 power achieving 92% within 13 seconds. They skipped the rest of the pre-take-off checklist and began accelerating down the runway.

The first officer called out V1. A second later, the captain abruptly pulled back on the yoke. This abrupt elevator input, going from 1.5° to 10° elevator deflection over one second, caused a rapid pitch up that peaked at a staggering 8.6° per second, as opposed to the expected 3° per second pitch up.

The aircraft lifted sharply into the air, travelling just under 120 knots computed airspeed, just above the computed VR (rotation speed). The first officer can be heard on the Cockpit Voice Recorder saying “Woah….woah…woah”.

The aircraft was travelling at 131 knots as they climbed to 11 feet above the runway. The stick shaker activated, warning of an impending stall.

From the outside, bystanders saw the CRJ 200 rolling to the right, then banking sharply and rolling to the left, only to roll back hard to the right. The aircraft was nearly inverted as they continued rolling right, climbing through 77 feet.

The timing on this isn’t exact but the first officer was still speaking, calling out “Sir, sir, sir!”

The right wing smashed into the runway, just before the intersection of taxiway Juliet. The CRJ 200 cartwheeled onto the east side of the runway and continued east, striking a cargo container and shed belonging to Air Dynasty Heli Services before bursting into flames.

The aircraft had taken off at 11:10:55. During the oscillations, the aircraft reached a peak of just over 100 feet above the runway. The FDR stopped recording thirteen seconds after take off, at 11:11:08.

Four fire vehicles were dispatched the moment the right wing struck the ground. The aircraft had fallen into a gorge, sliding down 130 feet over the next four seconds. The fire vehicles struggled to reach the crash site. The first fire vehicle found a position and began spraying water while the next two vehicles paused, not immediately taking part in the fire-fighting efforts. Rescue personnel helped the captain who escaped from the cockpit embedded in the cargo container but no effort was made to rescue the remaining crew from the cockpit before it burst into flames.

The front of the passenger cabin was immediately fully engulfed in fierce flames, with no possibility of rescuing anyone from the front.

In addition to the flight crew, there were sixteen people seated in the passenger cabin, including a four-year-old child. Of the nineteen on board, fifteen were killed in the impact. Three were pulled from the wreckage of the cabin; however they died en route to the hospital. The captain, who suffered serious injuries, was the only survivor.

Four months before the accident, the aircraft underwent an inspection for the renewal of the Certificate of Airworthiness. The report doesn’t specify the results of this inspection other than that the MLG TBO (Main Landing Gear Time Between Overhaul) was set to expire in April. The airline received an extension to do this maintenance, giving them until June to complete the work needed. In April, Saurya also received a special permit for a test flight to renew the now-expired Certificate of Airworthiness.

But they didn’t get the maintenance done in time. On the 19th of June, a month before the accident flight, the extension for the landing gear maintenance expired. The aircraft registered as 9N-AME was grounded.

The operator was clearly struggling to get the CRJ 200 back into service. The fact that they needed extensions and special permits to deal with the ongoing certification issues suggests that the airline was struggling to maintain their fleet properly, even though the fleet consisted of only one aircraft at this point.

Saurya repeatedly arranged for short-term storage for the aircraft until the 22nd of July, two days before the accident, when both main landing gear assemblies were finally removed and reinstalled as per the necessary overhaul.

The following day, the Air Transport Division of the Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal approved a one-time non-revenue ferry flight for 9N-AME to fly to Pokhara International Airport, where it would undergo base maintenance (C-check).

The question remains: why were there 19 souls, including a young child, on board an aircraft flying for maintenance on a special ferry flight permit?

That morning, the day of the accident, the aircraft underwent a return to service check.

It’s important to note that the investigation found no mechanical defects that contributed to the accident. The maintenance work was completed properly, and flight data showed all aircraft systems functioned normally during the take-off sequence.

The loading of the aircraft, on the other hand, was cause for serious concern. The load sheet estimated 600 kg of baggage but they only found 402.5 kg at the crash site. Then they found an additional 98.6 kg had been removed from the crash site without being processed. This baggage was recovered from Saurya corporate offices in what the investigators later called out as evidence tampering.

Notably, this still leaves the aircraft 100 kilograms short of the stated load for the flight.

The ground crew said that the hold was full and additional cargo had to be loaded into the aircraft cabin. This was done in a haphazard manner, with lubricants, contact cleaners, wheel chocks, toolboxes and food items simply dumped onto seats and in the aisles without being secured. Among the wreckage, investigators found hydraulic fluid spilt on the floor of the cabin and evidence of dangerous goods, including flammable contact cleaner (classified as UN1950 hazardous material), loaded without proper documentation or securing. Saurya Airlines did not have a permit for transporting dangerous goods.

The captain and the flight dispatcher were aware that this baggage had been loaded into the passenger cabin but did not see it as a point of concern.

Apparently, this was business as usual.

The crash was made worse by the fact that Tribhuvan International Airport’s runway safety areas didn’t meet international standards established by ICAO Annex 14. The investigation found that the low-lying areas on the east side of the runway, where 9N-AME crashed, failed to comply with requirements for runway strips.

Runway strips serve as safety zones for aircraft that overshoot, overrun, or veer off runways during takeoff or landing accidents. They must be free of obstacles and maintained to allow rapid access for rescue and firefighting vehicles. At Tribhuvan, the non-compliant areas surrounding the runway had been flagged for over a decade without meaningful correction. If the runway strip had met ICAO standards, the crash would have taken place within the safety area. Instead, the wreckage was in rough and uneven terrain, creating confusion for rescue crews and delaying their response.

The crash area had never been included in emergency exercises, so the firefighting and rescue crews had no plan for accessing that terrain. Only the lead unit engaged in active firefighting. The other three vehicles arrived but stopped short of the wreckage, uncertain about access and unclear on their orders. They had access to foam tenders and dry chemical agents but used only basic water spraying.

To make matters worse, the emergency gate nearest to the crash site was closed, blocked by construction materials and other debris.

The result was a disjointed and incompetent emergency response when every second was critical. The investigation concluded that with proper rescue coordination and compliant runway safety areas, the first officer and maintenance technician in the detached cockpit may have survived, instead of being swallowed by flames while rescuers made no co-ordinated effort to rescue them.

There was no cabin crew on board, despite the presence of 16 passengers, including a child. No safety briefing was made, nor was anyone on board to ensure that basic safety measures were complied

with. Most of the occupants of the passenger cabin were killed by blunt force injuries. The rescue and fire fighting teams did not document whether the passengers were wearing seatbelts, which leaves

us with little to go on as to the injury patterns.

All this, on what was meant to be a special approval ferry flight. Nepal has multiple regulations regarding ferry flights, referencing the EU guidance that ferry flights are for non-airworthy civil aircraft. However, the CAAN documents are not completely clear, defining ferry flights as Special VFR flights with no passengers carried in one document and that persons on board shall be limited to “flight crew and maintenance people” in another document, FOR(A) Nepal Para 8.7.4.

The Saurya staff were not essential to the flight, but strictly speaking, the majority of them were maintenance people, which could arguably be justified based on paragraph 8.7.4. Even if we accept that, however, it does not explain why family members were on board, including a small child, the improperly loaded cargo or why the flight was operated without cabin crew.

We cannot get the answers to these questions. Those killed in the crash included Saurya’s Manager of Continuing Airworthiness Management Organisation, which is deeply ironic under the circumstances, but also means that the investigation could not determine the justification for loading the aircraft with non-essential personnel. Also killed were the Maintenance Manager, the Airline Safety Manager and QA manager.

It is difficult to imagine that they did not think to comment on the hazardous flammable goods simply tossed into the cabin.

Because there were no formal check-in procedures for those boarding the plane, the cargo and personal items were not weighed. The ground crew (bizarrely, mentioned as the marketing department in the report) were given a crude estimation of the baggage weight, which they wrote down for the loading manifest. The cockpit voice recorder includes a conversation between ground and maintenance personnel discussing the rough weight estimation, which the flight dispatcher then listed as 18,137 kg on the load and trim sheet.

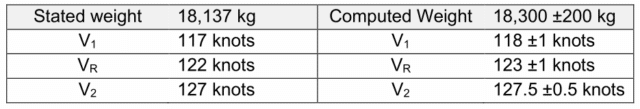

The investigators attempted to reverse-engineer the actual aircraft weight using physics and flight data. Remarkably, the actual weight was not far off, around 18,300, plus or minus 200 kilos.

Based on this, the V-speeds should have been calculated at V1=118, VR=123, V₂=127.5 knots.

But we know that the crew actually rotated at under 120 knots, closer to V1 than VR. Sure, the aircraft was heavier than estimated; however that should only have led to a discrepancy of one knot for V1 and VR and only half a knot for V2.

The problem, it turns out, was the speedcard.

Remember those base speeds for 18,500 kg take-off weight?

- V1: 109

- VR: 115

- V2: 125

Unfortunately, those numbers were wrong. In fact, the V-speed references on that page were a direct copy of the correct V-speeds for a take-off weight of 17,500 kg.

The ground crew had estimated the weight of the aircraft to within a few hundred kilos. But the speedcard in the aircraft was 1,000 kilos out.

From the report:

The fact that none of the flight crew noticed the blunder in the speedcard though-out the history of the airline is a critical failure of the flight operations and safety management.

The speedcard had been wrong for ten years. No one at Saurya Airlines had ever noticed.

The captain, the only survivor of the flight, recalled that he had not confirmed the V-speeds calculated by the first officer, which he should have done as standard. But he was also not aware of the error in the speedcard and so would not have questioned the V-speeds, which the first officer had calculated correctly based on the speedcard data.

Now we see the true issue: a rotation speed of 118 knots instead of the required 123 knots.

The stall speed of the CRJ 200 was 111 knots. The captain, as Pilot Flying, rotated at just under 120 knots, only 9 knots above the stall speed. He quickly deflected the elevator from 1.5° to 10° over just one second, three times faster than standard rotation, pitching up abruptly as if trying to unstick the aircraft by brute force.

Both wings reached a dangerously high angle of attack, causing the stick-shaker to activate to warn the pilots that the aircraft was at risk of stalling. Based on historical data, the aircraft’s right wing was prone to stalling first, true for both of the airline’s CRJ 200s, actually, and that’s what happened here.

The CRJ 200 suffered an asymmetric stall as the right wing lost lift. The aircraft began to roll to the right with a bank angle of 26°. The captain reacted as the stick shaker activated, rolling left and holding it for two seconds. The aircraft rolled left 55° at 50 feet above the ground. The aircraft lurched up to 100 feet before pitching back down. They rolled hard to the right to 94.6° (nearly inverted). There was no chance of recovery.

The first officer tried to intervene but was unable to communicate effectively, repeating “woah” and “sir” instead of something useful like “reduce pitch!”

The wrong V-speeds set up the dangerous conditions. However, it was that initial excessive pitch up by the captain that started them on the path to loss of control. A normal rotation should be maximum 3° per second. There is a warning in the CRJ 200 manual that the type is susceptible to control issues on take-off with excessive pitch rates/overrotation. The Saurya Airlines take-off procedures, however, did not mention the importance of a 3° per second rotation rate.

In fact, high rotation rates of over 4° per second were common at Saurya. The aircraft’s flight data recorder showed 18 instances of excessively high pitch rates above 5°/second over the previous year. The most extreme cases were a take off at 5.8°/second in January 2024 and 5.5°/second in March 2024. That March 2024 flight was the captain, the same who would become the sole survivor of the accident flight.

The accident flight’s 6.5°/second was the highest ever recorded. However, this wasn’t just a simple pilot error on a single flight; it was the airline culture. No one at Saurya Airlines was monitoring or correcting this dangerous technique.

About those rotations… We’re lucky to have that historical data because the investigation also found that the Flight Data Recorder had been malfunctioning since at least 2021 without anyone noticing.

It was the responsibility of CAAN (Nepal’s civil aviation authority) to verify the FDRs to confirm that all mandatory parameters are being recorded. Annually. They did not notice anything wrong for at least four years.

Key missing parameters included Control column forces (how hard pilots pushed/pulled), Control wheel forces (roll inputs), Rudder pedal forces and positions and brake pedal applications. Without the control force data, investigators can’t recreate how aggressively the captain pulled on the controls or whether the first officer tried to physically intervene.

The lack of oversight by the regulator was not a one-off issue. A safety audit in September 2023 found that CAAN had inadequate training for its inspectors. The audit identified systemic weaknesses in the CAAN safety programmes and the frameworks for monitoring safety systems. Additionally, CAAN was struggling with resource shortages and personnel management issues, which directly affected its ability to oversee airline operations.

I know this has been a very long article but, truly, this accident is hard to believe, let alone explain. Every level of the aviation safety system failed simultaneously: crew procedures, airline operations, aircraft performance data, regulatory oversight, airport emergency response, and even post-accident evidence handling.

The final report lays the blame firmly at Saurya’s failures.

Most Probable Cause

The most probable cause of the accident was a deep stall during take-off because of an abnormally rapid pitch rate commanded at a lower than optimal rotation speed.

Contributing Factors

The contributory factors to the accident are:

- Incorrect speeds calculated based on erroneous speedcard. The interpolated speedcard of the operator for 18,500 kg TOW mentions incorrect V-speeds for take-off. This error in the speedcard went unnoticed since its development. There was no acceptance/approval of the speedcard booklet.

- Failure to identify and address multiple previous events of high pitch rate during take-off by the operator.

- The operator showed gross negligence in complying with the prevailing practices of ferry flight planning, preparation and execution. There is a lack of consistent definition of ferry flights.

- Gross negligence and non-compliances by the operator during the entire process of cargo and baggage handling (weighing, loading, distribution and latching), while violating the provisions of operational manual and ground handling manual. The load was not adequately secured with straps, tie-downs, or nets, while the flight preparation was rushed.

The report concludes with a collection of immediate actions and longer-term systemic changes. Saurya Airlines has since revised and verified their speed cards and implemented stricter take-off procedures, with targeted retraining for pilots on stall recognition, pitch control and aircraft performance monitoring. They have also introduced a Flight Data Monitoring system to detect unsafe trends. Cargo handling procedures were overhauled.

Emergency response protocols at Tribhuvan International Airport have been updated, and stricter evidence-handling procedures were mandated after post-crash investigation issues.

The Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal says that they have tightened their oversight with increased ramp inspections, regular operational audits, and new rules for aircraft loading and documentation.

I wish Nepal’s aviation industry all the best, but it’s hard to feel confident about their success given the environment that allowed such a breakdown to occur in the first place.

People sometimes ask me what airlines I would avoid flying with. My answer is that it’s not any individual airline that causes me concern so much as the regulator. When the system is broken at the top, the failures filter down.

Nepal’s Civil Aviation Authority will have to do a lot more to earn my trust in the airlines they claim authority over.

Great article! However, a little concerned that you’ve started using ML generated voiceovers… A lot of these models are based on training recordings of people who did not consent for their voices to be used this way, not to mention the environmental impact of the datacentres required to run the model. I understand that you’ve done this for accessibility, but visually impaired people usually prefer to use their own screenreader software which is more flexible than a simple audio file.

Hi! For long posts, it would be nice to have an audio version but I don’t have the time or skill to do it myself. To address your specific concern, this is my voice, which I have specifically cloned in order to create the audio file.

The definition of a clusterfrak. One of the few accidents in memory where failure was the only option. From an aviation authority that seems incompetent, an airport with abysmal safety standards, an airline that should have been shut down years ago, and an unqualified crew. The expression “accident waiting to be happen” screams in my head. The irony that the people responsible for the airline’s safety were some of the victims is not lost to me.

I think this accident report can be summarized by the phrase “since 2013 the European Union has banned all Nepali airlines from operating within its airspace due to safety concerns”

The phrase “the holes lined up” is used frequently on this blog, but in this case there were So. Many. Holes….

Do we have any idea how many countries actually have training courses for commercial pilots? Germany seems a long way to go, but running a flying school for jet airplanes is probably so expensive that there aren’t many such schools. That brings up a corresponding question: are there any training courses for government agencies that regulate flying, or do such agencies “just grow”? And are there any refresher courses to make sure regulators don’t get into bad habits? (Assuming they were ever out of bad habits — that’s not clear from this story.)

The jamming-on of random people sounds a bit like Douglas Adams’s description of getting to Komodo to document monitor lizards for “Last Chance to See” — but much worse. From the job titles you list, I get this vision of managers and family members taking advantage of what seems like a free flight, on the grounds that the rules didn’t matter because nobody was paying; one wonders whether this was as common as the violent takeoffs you describe.

Nit: ISTM that 94.6 degrees isn’t “nearly inverted”; isn’t that more like “teetering on one wing”? It’s still not a posture that I expect a CRJ to be comfortable in.

A belated question: why was the “airline” responsible for the speed card? ISTM that such data would be consistent over all aircraft of a given model and so should be provided by the manufacturer. I can see that individual aircraft would have different internal configurations (e.g. more or fewer seats) that would affect the empty weight — but that’s a fixed number that would be the basis of the calculation for gross weight, which the speedcard uses.

The manufacturer provides the speeds for whole tons (18,000 kg, 19,000 kg TOW). Saurya decided to make it easier for pilots and included the interpolated numbers for half-ton values such as 17,500 and 18,500.

Thank you for the excellent write-up, Sylvia! This turned out so much worse than we thought when we first learned of the event.