Crash at Pensacola: “I wasn’t ridiculously low”

On Tuesday the 13th of August 2019, a Cessna 172 Skyhawk, registration N84287 crashed into a sand bar on the Escambia River near Jay, Florida, near the Alabama border.

The pilot held both commercial pilot and flight instructor certificates with over 1,000 hours flight time, 798 hours in the aircraft make and model. The aircraft was a high-wing single engine aircraft with a fixed tricycle landing gear, built in 1969.

The pilot was doing pipeline patrol work, surveying a pipeline system by flight looking for damage, defects or disturbances. He said that he enjoyed the work, although it was often long hours, around eight or twelve flying hours. He worked alternating weeks of pipeline flying. The operation never pressured the pilots to do anything unsafe or hazardous, he said, and were very aware of basic issues like having an extra half hour of fuel on board. “I’ve never felt unsafe,” he said after the accident. As far as he knew, there were no maintenance issues with the aircraft, other than the oil pressure running a little high.

The day before the accident, on Monday, he’d been flying pipeline patrol but the weather closed in and he wasn’t able to return to Brewton, Alabama, the operator’s base, to finish off his paperwork and the working day. Instead he flew to his home airport of Pensacola, Florida, about 20 minutes south of Brewton. He landed around 8 or 9 in the evening and went to bed a few hours later.

The following day, the day of the accident, his recollection was that he didn’t wake up until 9 or 10 that morning, as he didn’t have any flight time scheduled; all he had to do was fly to Brewton to finish off that paperwork.

He topped up on fuel at Pensacola and then flew to Brewton, where he finished off the administrative work that he needed to do, which only took an hour or two. Then he got back into the plane and lined up on runway two-four.

That’s the last clear memory he has of that day.

Shortly after noon the Vice President of the operator (and the owner of the aircraft) received an unexpected phone call from someone who identified himself as Sergeant Smith to say that the Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT) in N84287 was going off. The VP said that as far as he knew, the aircraft was parked in Brewton Alabama but he said he’d check on it and call back. Staff at Brewton told him that no, the aircraft had departed about twenty minutes ago for Pensacola. Pensacola told him that he definitely hadn’t arrived and in fact ATC had no record of the inbound aircraft. The owner got the GPS coordinates from Sergeant Smith and passed the details on.

Then the VP took off from Brewton in another company plane with his son to check out the coordinates at low level. They quickly located the crash site on a sandbar on the Escambia River, about ten miles southwest of Brewton. The aircraft was upside down with both wings deformed and the fuselage was cracked and buckling. The nose landing gear was sheared off and the main landing gear was bent back. The propeller spinner was crushed and one of the blades had been bent into an S, with scuff marks clearly visible on it. The opposing blade was bent and the tip was gouged.

The VP could see the pilot in the wreckage, clearly injured and unconscious but, he thought, alive. He climbed to 1,500 feet and contacted Pensacola to report the wreckage and ask for a helicopter to get the pilot out.

I have you 5-5; I need some help. I need a Life Flight helicopter dispatched to my location. We’ve got an aircraft down The pilot appears to still be alive.

He also contacted the Escambia County Sheriff’s Office in Alabama to ask for support. They alerted the local rescue agencies while the owner circled the site, reporting the state of affairs to the Sheriff’s Office and Pensacola Terminal Radar Approach Control.

The controller had just started his shift at Pensacola Approach when he received the initial call from the VP and confirmed that he hadn’t seen the missing aircraft. When the VP called him back to report the crash site, the controller tried to find a helicopter who could rescue the pilot.

There was a Life Flight (air ambulance) crew in the area but they had just completed a mission and were in a mandatory cooldown period. He asked some Navy helicopters to respond but most of them didn’t have fuel and there were thunderstorms in the area.

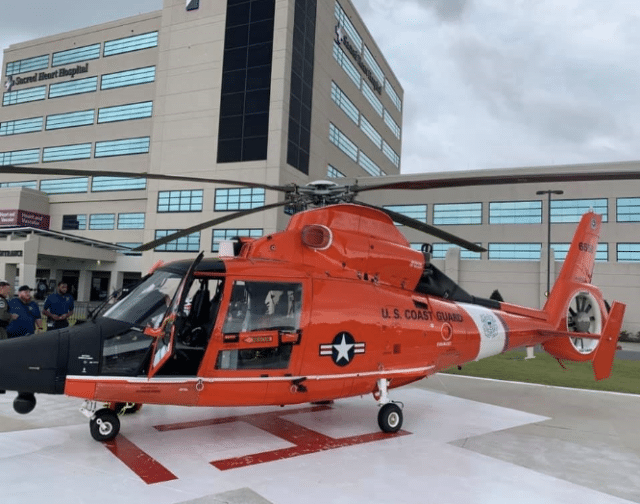

The coast guard had a base in Mobile, so the controller contacted Mobile ATC and asked if they had any Coast Guard helicopters talking to them at that moment. The Coast Guard base in Mobile is for training and aircraft testing, not search and rescue, but Mobile ATC asked a Coast Guard pilot on a training mission in a MH65E helicopter to please change frequency to Pensacola and get the details directly.

The pilot was a Lt. Commander and had over ten years of experience with the Coast Guard. The controller asked the helicopter pilot if he could try to get to the aircraft crash site, explaining that the pilot of the plane was badly injured.

I felt like if anybody was going to be able to do a rescue and get this pilot out of there, it was going to be the Coast Guard.

He spent the next 25 minutes vectoring the Coast Guard helicopter to the crash site, helping him to avoid the squall line of the thunderstorms. In the meantime, an Emergency medical services team had reached the sand bar on foot.

The helicopter pilot said the unplanned search and rescue was only possible because of the help from the controller.

This was the first search and rescue case in the MH65 Echo aircraft so it was kind of unique. We didn’t plan it that way but our aircraft had an all-new glass cockpit and brand-new weather radar, which actually helped us that day.

We had a very good crew but we didn’t have a rescue swimmer on board so theoretically, we were not SAR capable.

The VP of the operation, still circling in his Cessna, and the controller at Pensacola were able to coordinate the rescue. The Coast Guard pilot kept the helicopter running at half power to keep it from sinking in the soft sand. As it was, he said that the wheels were halfway down into the sand during the brief time they were on the scene.

They picked up the injured pilot and an emergency medical technician and flew to Sacred Heart Hospital in Pensacola. The Coast Guard pilot had never landed there before but he was put in touch with a Life Flight pilot who gave him all the details for a safe landing.

Afterwards, he was full of praise for the Pensacola controller.

[The controller’s] demeanor, everything on the radio, was fantastic. He painted a perfect picture of where we needed to go, what we needed to do and who was on the scene.

Once the controller heard that the pilot had been admitted to the hospital, he went out to his car and just sat there, trying to come down from the incredible adrenaline rush. Later, he contacted the Coast Guard pilot to say thank you. They’ve been in touch a number of times since then.

The FAA also got in touch, not surprisingly, and spoke to the pilot about what had happened that day. His recollections of the entire day were hazy. When asked how long the flight was from Pensacola to Brewton, he said “Not long…it’s so fuzzy. I kind of got rattled.”

There was no flight plan but he was sure he must have been flying to Pensacola. He remembered taking off from runway two-four and flying southwest and then putting the aircraft into a landing attitude. He had no additional recollection and no idea why he was trying to land on the sandbar.

He was not on the direct track to Pensacola but this was normal, he said, as generally flew southwest to avoid the Whiting Field Naval Air Station airspace. He agreed that the flight normally took about twenty minutes. But he had no idea why he was configured for landing, only that he could remember “going down” and trying to keep the aircraft coordinated to avoid damage. He thought his last altitude was at 1,500 feet.

The FAA interviewer pointed out that as the area wasn’t congested, the pilot could have been flying as low as 500 feet without being in violation.

If you were sightseeing or…if you might have been sightseeing, it would be great to disclose that. Or if there was an engine problem and you were losing altitude. Do you have any recollection?

The pilot didn’t; however he was sure he wasn’t ridiculously low and he dismissed the idea of sight seeing. “I wasn’t very low level.”

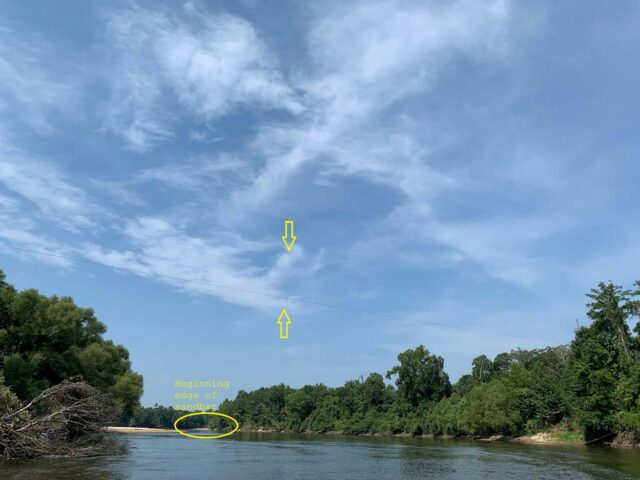

The scuff marks on the propeller had been made by impact with a power line which was about 60 feet above the river, with the marks on the left leading edge where the wing had been struck by a severed power line.

The pilot had no recollection of striking the power lines spanning the river or the crash into the sandbar.

His father, who was present for the interview at the hospital, pointed out that there should have been safety globes on the wires across the river. The investigator said that he was unsure of the regulatory requirements for marker balls but that he would look into it.

The father offered an additional opinion about an engine failure that may have contributed to the pilot’s landing situation; he admitted that it was speculation and I informed him that we would be examining the engine as a part of the investigating.

The NTSB would do an engine teardown and try to figure it out, he reassured them. “They are thorough.”

The pilot was apologetic. “I’m sorry I’m not more help. I don’t remember anything until waking up in this bed and the surgery was done.”

There was nothing wrong with the engine and no reason why the aircraft should have been low enough to strike the power cords. The GPS data from the Cessna told its own story but truth is, it didn’t answer any questions.

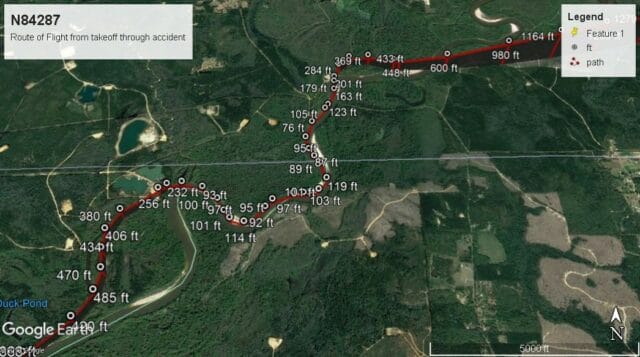

The full record of the flight had been saved as GPS data. After departing Pensacola, the Cessna 172 climbed 250 feet and turned northwest, reaching 900 feet above mean sea level in a climbing turn and then southwest to 1,294 feet travelling at 104 knots.

Then the aircraft descended to 333 feet above mean sea level and made a descending turn, arriving directly over the Escambia river at 76 feet above mean sea level and 92 knots. The river is about 45 feet above mean sea level.

The pilot then clearly followed the river for about a mile and a half at low level. At a sharp bend in the river, the Cessna climbed to 485 feet mean sea level and then descended hundred feet and began following the river again. The aircraft continued to descend as it followed the path of the river at 110 knots, reaching 117 feet above mean sea level about 700 feet before the power lines.

At the point of impact, the aircraft was at 105 feet above mean sea level and travelling 87 knots. The pilot had been tracking the river for about 4.5 nautical miles (about 8 kilometres).

Additional examination of the wreckage showed both cockpit control yoke handles were attached to the control column. The aileron control cables exhibited signs of tensile overload, but were traced to their respective locations and were connected. All the control cables were attached to their respective control surfaces to the rudder, elevator and ailerons and control continuity was confirmed. Engine drivetrain continuity was established, and the intake valves and exhaust valves on all four cylinders were functional. Thumb compression was present on all four cylinders, and internal examination using a borescope revealed no anomalies. The top spark plugs were examined, and the electrodes appeared normal; the No. 1 spark plug was oily. Both magnetos were functional and produced healthy spark from all leads. There were no anomalies discovered with the engine or engine components.

An investigator attempted to follow up with the pilot, who had been released from the hospital and was recovering at his father’s house. The pilot’s father explained that his son was in a lot of pain and that he would relay questions and answer on his son’s behalf.

The pilot still did not remember anything about the flight, he said, other than that the day before, bad weather meant that the pilot wasn’t able to complete his pipeline patrol. He said the pilot clearly remembered flying to Pensacola and believed that he was well rested. He was under no pressure to resume his work or get back to Brewton.

FAA regulations prohibit flying less than 500 feet above uncongested areas unless approaching to land or taking off, which the pilot was clearly below. But there was no clear reason why he would have been tracking the river on a route that he flew regularly, let alone why he might have configured for landing.

The final report includes this paragraph, presumably in response to the father.

The Advisory Circular (AC No. 70/7460-1L) sets forth standards for marking and lighting obstructions that have been deemed to be a hazard to navigable airspace and according to the AC, markers were not required on the power lines. The VFR Aeronautical Chart at the site of the accident is represented with a “power transmission Line” symbol.

The final report cites the probable cause as the pilot’s improper decision to fly over a river at very low altitude, which resulted in a collision with power lines.

The controller, Marcus Troyer, received a letter of commendation from the US Coast Guard Aviation Training Center and was nominated for an ARCHIE award.

On the NATCA podcast, you can hear the original radio broadcasts and Troyer talking to US Coast Guard Lt. Commander Brian Hedges, who was the pilot and aircraft commander on the helicopter, about the events of the day:

It’s no exaggeration to say that between the two of them, they saved that pilot’s life.

Sounds like CO poisoning. Did the medicos check for that?

Oops, I didn’t post the link to the report; adding it now. There’s no medical information but I’m not sure that CO poisoning maps with following the river quite so deliberately.

I wonder if he was ‘vaccinated’ recently and suffered a stroke. Is there any record of his having had a d-dimer test by any chance?

Sine this happened on 13-AUG-2019, we can rule out COVID-19 vaccinations as a cause.

It’s a 1:100 000 risk anyway, and the accident report would have mentioned it, so Mike’s comment just looks like anti-vaxx propaganda.

A Covid infection carries a 10 times higher stroke risk than a vaccination, but Mike didn’t think to ask for that.

Oh, Mike’s comment is entirely propaganda. It was propaganda for a course of events that is truly impossible, rather than just improbable, and deserved to be called as such.

I like how the “bear claw” marks on the cowling reminded me of the wire strike marks on the RAF Chinook that was on the blog before. They’re very distinctive!

I’m not sure why the aircraft was said to be “configured for landing”, the gear is fixed, and the report says the flaps were stowed?

I haven’t accessed the docket yet (it’s linked from the report), but I’d like to know whether the pilot tried to fly “under the radar” to cross restricted airspace? And I’d like to find out how the pilot’s father knew there weren’t any marker globes on the powerlines, was he shown pictures? since the pilot had no recollection of them.

What restricted airspace is there to dodge? I’ve looked at Googlemaps and don’t see much of anything on the ground between those points except the NAS — which he would have been well clear of on the course he was flying, regardless of altitude. Does anyone have a chart that shows airspace restrictions for that area?

I agree with Sylvia that this doesn’t sound like CO poisoning. (The focused flight doesn’t sound to my limited knowledge like any toxin, but ISTM that CO is especially unlikely as it would dissipate — CO poisoning usually happens because combustion exhaust is fed into a closed space.) ISTR that Flying reported some decades back on tests showing that people high on marijuana tended to focus on one task instead of taking in everything (e.g., they’d nail the needles on a simulated instrument approach and never flare), but toking before flying doesn’t seem likely to me.

Yes, you can see charts online at many places, like skyvector.com, vfrmap.com, or directly from the FAA.

Link to Skyvector showing a direct track between 12J and PNS: https://skyvector.com/?ll=30.762449674923218,-87.12689208407939&chart=301&zoom=2&fpl=%2012J%20undefined%20KPNS The crash site is to the southwest of 12J by about six miles, about where the river meets the isogonic line.

The article does not say he was trying to avoid “restricted” airspace, just that he was avoiding “Whiting Field NAS airspace.” You can see that a direct track between the two airports goes through the outer ring of the Whiting Field Class C. Of course he would have had to contact Pensacola Approach at some point in order to land at PNS, but many pilots prefer to fly around Class C as much as possible instead of trying to go through.

JS has it right — the point was that the crash did not take place on a direct route between Brewster and Pensacola but that fits in with the standard route the pilot would take, heading southwest to avoid that airspace.

I have a feeling “configured for landing” is my fault — I have looked for some reference to the flaps or any other hints and I don’t see them and there is a reference to him being in an approach attitude. As the pilot remembers setting up for landing or a landing attitude or something like that, I think I must have converted that into my head as configured for landing.

The NTSB interview would not have been immediate; the father seems very involved in his son’s defence, and I feel like he had plenty of time to see photographs from the site (it was reported in all the local media) or even to hike to the location.

“restricted” was the term used in Mendel’s comment above. If I’m reading the chart correctly, even a straight line between departure and destination could have been flown as high as 1399′ MSL() without going through the NAS’s space; there was no excuse for being anywhere near low enough to hit that power line.

() Yes, I know altitude can’t be controlled that precisely — but even if he wanted to sightsee under the lip of the NAS’s Class C instead of going around, he would have been safe from towers and hills (as well as the power line) at 1000 MSL. (That’s still on the low side — it would limit his options in case his only engine failed and he had to find a place to set down — but at least it’s clear of nearby obstacles.) GIven that he was on course to go around the Class C, he could have been much higher without even having to talk to any controller before PNS.

“His father, who was present for the interview at the hospital, pointed out that there should have been safety globes on the wires across the river.”

“The father offered an additional opinion about an engine failure that may have contributed to the pilot’s landing situation; he admitted that it was speculation…”

“An investigator attempted to follow up with the pilot…The pilot’s father explained that his son was in a lot of pain and that he would relay questions and answer on his son’s behalf.”

The pilot still did not remember anything about the flight, [the pilot’s father] said.”

Does anyone believe that the pilot’s father habitually requires his son to take responsibility for his actions, but in this one instance suddenly decided to intervene and shield him from the investigators? Nonsense. People don’t change their attitudes that much that quickly. The father has always shielded his son from the consequences of poor judgement and bad decisions.

If I had a Daddy like that, and I flew the company plane into some power lines — I’d quickly develop “partial retrograde amnesia” too.

Something smells fishy here and it is not coming from the Escambia River.

Hats off to the Controller and the Coastguard Air Crew. Unsung heroes too many times to count.

It’s more than fishy I’m afraid.

“The pilot then clearly followed the river for about a mile and a half at low level.”

The final report states that the probable cause was “improper low flying”. Sadly, I must concur.