Bomber 139’s Third Run: Downhill to Disaster

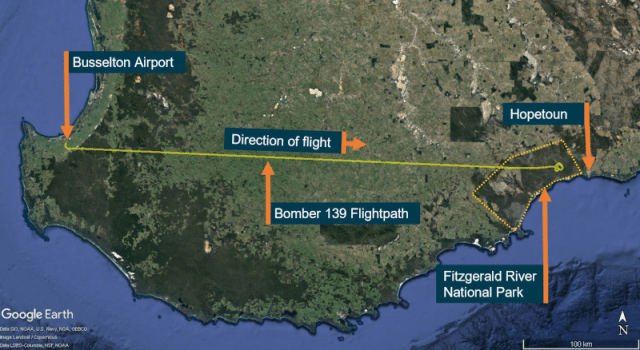

On the 6th of February 2023, a Boeing 737-3H4 Large Air Tanker crashed into a ridge line of 222 feet elevation in Fitzgerald River National Park in Western Australia.

There were two pilots on board. The captain was very experienced with multi-engine air tankers and held his United States Forest Service (USFS) Air Tanker Training Pilot qualification. He had 8,233 hours flying experience, including 1,399 hours on the Boeing 737 and 5,500 hours aerial firefighting experience. He spent several years at the US National Aerial Firefighting Academy teaching other aircrews before joining the operator and had become the director of operations there in 2017. The first officer had 5,852 hours of flying experience with 500 hours aerial firefighting experience. However, he did not have as much experience with large air tankers, with just 128 hours on the Boeing 737.

The Boeing 737 was 28 years old and registered in the US as N619SW. It had 69,016 hours when the operator purchased it in 2017.The Boeing was modified for its new purpose a an aerial firefighter tanker with the installation of a Retardant Aerial Delivery System. Two tanks were installed to hold fire retardant, with a total capacity of 36,000 pounds (~16,300 kilos). The converted Boeing 737 bomber was given the call sign Bomber 139.

In the cockpit was a user interface with a switch on either side. If either crew member activated their switch, the door would open to drop a predefined level of fire retardant, based on the tank levels, ground speed and aircraft height above the ground. There was also an emergency dump switch to dump the full load in under two seconds.

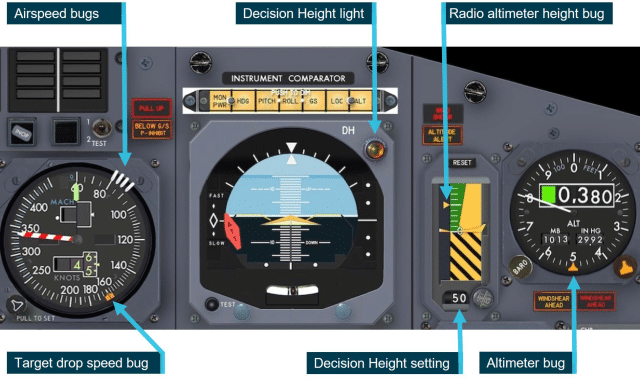

Both instrument panels had radio altimeter indicators which displayed the height above the ground when flying below 2,500 feet above ground level. It was possible to set a decision height (DH) on these altimeters, which activated a light marked as DH. As an example, you can see in the image above that the decision height is set to 50 feet above the ground.

On the 6th of February, fire controllers spotted a dangerous fire west of Hopetoun, Western Australia. The fire was burning through an area with high fuel loads, meaning it could spread quickly. They called in aerial support to help contain it.

The State Operations Air Desk coordinated the aerial response. They sent out several requests for aircraft throughout the day.

Bomber 139 was one of those who responded. The aircraft and crew made two successful flights from Busselton airport, dropping retardant on the fire and returning to base. The accident flight was their third flight of the day. The flight crew described their mental fatigue level as fine but not at peak.

Three aircraft worked together at the site:

- A smaller aircraft, referred to as Birddog, gathering intelligence to determine the best flight path, guiding the bomber to the right spot and using a smoke generator to tell them where to drop

- Bomber 139, the large air tanker who would carry and drop fire retardant following the Birddog’s guidance

- An Air Attack aircraft circling high above to coordinate the entire operation.

At 15:19, the original Birddog who had been providing the reconnaissance support for the previous drops (callsign 125), needed to refuel. Before leaving, the crew took their replacement, Birddog 123, on a familiarisation flight around the fire zone. They explained the layout of the fire and the plan for the retardant drops but did not mention any hazards in the area.

Ten minutes later, Bomber 139 departed Busselton with a recorded gross weight of 124,640 pounds, of which the fire retardant payload was 35,200 pounds. At 15 minutes out, the captain contacted Birddog 123. Birddog 123 responded with the current QNH setting (barometric pressure). The captain of Bomber 139 acknowledged the altimeter setting and said they would contact the primary air attack aircraft when they were five minutes from the fire.

The Air Attack aircraft cleared Bomber 139 into the zone with a ceiling of 2,500 feet. Birddog 123 confirmed the area was clear; no ground personnel were expected for another hour.

The captain of Bomber 139 was the Pilot Flying and the first officer was Pilot Monitoring. The first officer briefed the captain on their target drop speed (VDROP) of 133 knots.

The captain reported that they had visual contact with Birddog 123.

Birddog 123’s pilot offered them two options:

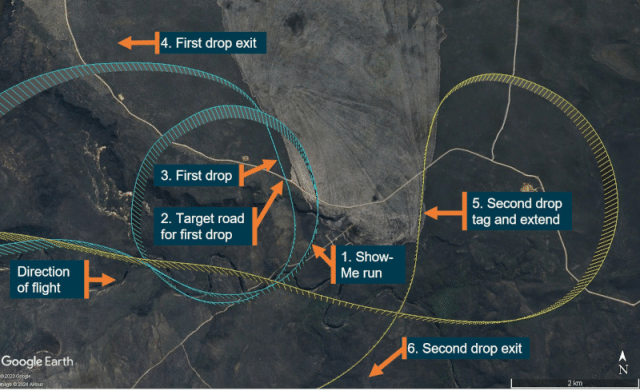

- A “Show-Me” run: a pass over the target to demonstrate the line and start point of the retardant drop, giving the Bomber 139 crew a preview of the terrain

- A low-level drop pattern (under 500 feet) following Birddog 123

The captain chose the second option, to follow Birddog 123 directly for the drop.

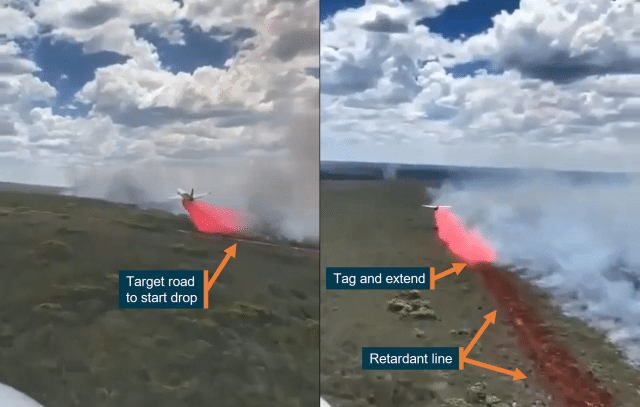

Birddog 123 briefed them on the target area: they would use a road as the start point to extend the existing line of retardant. They agreed to use right-hand circuits, keeping the smoke to the left.

Bomber 139’s captain reported that they were in position and then asked the first officer to complete the pre-drop checklist.

The operator’s procedures required calculating a target drop speed (VDROP) based on the aircraft’s configuration specifically, 1.25 times the minimum steady flight speed. After each partial drop, this target speed was recalculated and lowered to account for the reduced weight of the remaining load.

The captain contacted Birddog 123 to say that their target speed would be 135 knots for final with flaps set to full (flap-40).

Birddog 123 briefed them on the drop: they expected a a straight exit with no hazards, but it would be a downhill approach. The target altitude was 500 feet descending to 400 feet.

A downhill approach, or flying downhill, is when a low-level aircraft is following falling terrain, which means that the aircraft must continue to descend in order to maintain the same height above the ground. A downhill approach is typically flown at idle engine power, as the aircraft will slowly gain speed in the descent.

After Bomber 139’s first officer confirmed that the checklist was complete, the captain commented that their approach path following Birddog 123 appeared to be high. Birddog 123 called to say they were turning for their final heading of 155° and that they would have good visibility once they cleared the smoke.

In the cockpit, the captain asked about the road serving as the start point of the drop. The first officer pointed to the road, which was just ahead of them. They were ready to go.

Birddog 123 repeated the key points of the briefing. “Start at the road and keep all smoke to the left. 3, 2,1, start. Your target altitude is 500 descending to 400 feet.”

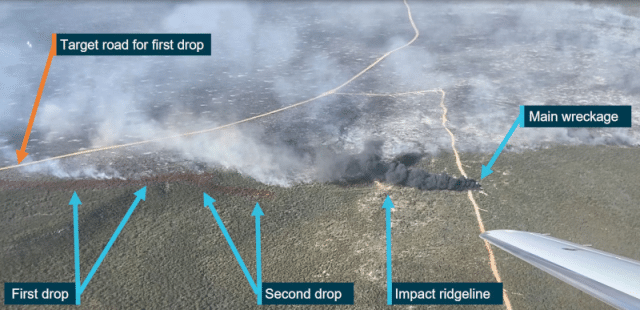

The captain confirmed that they had the road in sight. They descended, with their lowest height being 78 feet above the ground. With the engines at 70% N1, they maintained 124 knots as they completed a nine-second partial drop, which emptied three-quarters of their retardant. The captain stopped the drop as their retardant line entered an already burnt area and reported the partial drop to Birddog 123. They would need a second pass to tag and extend the first drop with the remaining retardant.

“…and head down off the hill,” said the captain on the radio, anticipating another downhill approach. The Birddog had briefed a ‘downhill’ drop with no hazards.

The first officer recalculated their target speed for the lighter load, which was now just 118 knots. As they followed Birddog 123 for the second pass, the captain again questioned the approach path. The captain asked Birddog 123 to slow to 120 knots for the next drop. Birddog 123 acknowledged and briefed the bomber crew for the final pass: “Tag and extend all existing retardant, …start at the hill as it pushes down. Target altitude 500 descending 400.”

The first officer reported that flaps were set to 40 and the pre-drop checklist was complete. The captain again commented again that he was unhappy with the approach path that Birddog 123 was taking. Something was clearly niggling at him but he didn’t elaborate.

Birddog 123 set them up for the drop. “This is final, fully retardant drop out here in a second. Standby… Retardant is right at our 12 o’clock… Three, two, one: tag and extend existing retardant.

They flew through the smoke drifting from the fire; the captain later said that they couldn’t see the target until they cleared the smoke at the start of the drop. The first officer agreed, saying that they couldn’t even find the target on final until Birddog 123 deployed smoke over the location to help them identify it.

They descended to 57 feet above the ground with the airspeed at 110 knots. The engines were left at a high idle (30% N1) as they extended the retardant line downhill.

During the drop, the aircraft recovered to 81 feet above the ground with their speed decaying to 107 knots.

The first officer did not make any call-outs about their deteriorating state, commenting later that his attention was fixed on the airspeed indicator and the radio altimeter.

The captain started to increase the thrust as they were quickly descending, with a peak of 1,800 feet per minute. The first officer’s hand moved to the flap lever, waiting for the call to retract the flaps, which would reduce the drag and allow them to climb away.

At the same time, the captain started to pitch the nose up. Their rate of descent slowed but so did the airspeed as they traded speed for altitude.

At the point when the thrust lever reached the setting for go-around thrust, the aircraft was 30 feet above the ground and still descending at 480 feet per minute, travelling at 105 knots.

The captain called “Fly airplane!” This is an urgent instruction to abandon everything else and focus on fundamental aircraft control. The stick shaker activated. The engines spooled up to their full power setting.

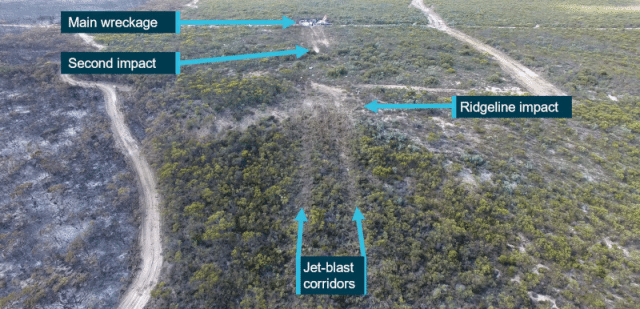

It was too late. They hit the ridge at 104 knots.

The Boeing 737 tanker, with the engines at 85-89% N1, kept going, smashing through foliage at just over two-hundred feet before hitting the ground a second time. Above them, Birddog 123 broadcasted MAYDAY on all stations.

As the bomber slid to a stop, the flight crew must have been surprised to find themselves sitting unscathed in the cockpit. The first officer immediately started the evacuation checklist. The cabin door had buckled and although they both tried, they couldn’t get it open. The first officer tried and failed to open the right-side window. The captain tried the same on the left-side window. Flames appeared; the aircraft was on fire. On a second attempt, no doubt driven by adrenaline, the two pilots managed to get the left-side window and climb out of the cockpit.

Two single-engine air tankers were above, dropping water with foam onto the fire, thinking the crew were still trapped inside of the Boeing. It must have seemed a miracle when they saw the captain and the first officer clear of the wreckage with only minor injuries. A helicopter quickly descended and picked them up.

Bomber 139 was destroyed.

Next week, we’ll take a closer look at what happened, and why.

I was relieved after reading, that thankfully on this occasion the crew survived! I am looking forward to the next instalment.

Thankfully the crew survived. These guys are heroes. They operate under difficult conditions in an unforgiving environment. There is absolutely no room for error. Zero. They do not have an ILS or published approach. Every situation is different, and can change in a split second. And if there is any change, so close to the absolute limits, it will inevitably be for the worse.

So if I make a few observations, this is close to arrogance. Let it be quite clear that I don’t really know the demanding conditions that these men (and women) operate under, and have to handle.

So here are my remarks, for what they are worth:

QNH: in the close proximity of a large burning area, this may create a mini climate; maybe with even more cells than one. Intense heat with air rising, over half a mile, maybe even less, the air pressure may fluctuate. Maybe not catastrophically, but in close proximity to the ground small fluctuations may be significant.

GPWS: very likely to have been disabled for obvious reasons.

A rising body of air causes updrafts, air rushing to replace the rising air from around the area, depending on the square mileage of the fire, may cause wind shifts, maybe mini bursts and, I guess here, a lot of turbulence.

Radar altimeter will be of limited if not dubious help so close to undulating terrain.

With a lot of drag, engines flight idle in a descent close to terrain and perhaps with hot air having a negative effect on the performance: an instant need to climb away could be nearly impossible at low IAS.. A 20 series Learjet would not have a problem with its ability to climb at 8000 fpm or more, even at maximum weight in the tropics. But the much bigger Boeing, with a much higher inertia, would need time to accelerate, engines require time to spool up, flaps to retract. And all that very close to the surrounding terrain. Very critical with possibly reduced performance due to shifting wind and heat..

The most important thing: okay, the firefighters had to do their job minus the Boeing. But the crew escaped. A reason for joy !

A riveting read, thank you, Sylvia!

I have a side note in my mind that the Americans are helping the Australians out with their bush fires, while the Australians help the Americans with their wild fires. Owing to fact that summer on the two continents occurs in opposite parts of the year, this arrangements works out well. The crews and their aircraft simply travel to the other hemisphere for the winter.

I looked up the spelling of “Hopetoun”, thinking that someone might’ve gotten it wrong, but it turns out that Hopetoun House, Scotland’s finest stately home, is an important part of European architectural heritage situated in South Queensferry, outside Edinburgh. It was completed in 1701. The Western Australian Hopetoun was established in 1900, named after the first Governor-General of Australia, John Hope, 7th Earl of Hopetoun.

Interesting comment, Mendel. There can be differences in spelling, due to the passing of time; the Scottish pronunciation may have been transferred phonetically. Not really unusual when especially in the 19th century geographical names were officially recorded. In the Scots accent “town” still may be pronounced as “toun”, even today.

And, fortunately, in cases of very pressing emergencies countries that are politically, even physically hostile, often offer help to stricken countries.