Bomber 139’s Third Run: What the Investigation Found

In order to follow this analysis, you’ll need to have the details of the flight and the crash from last week’s article about the flight.

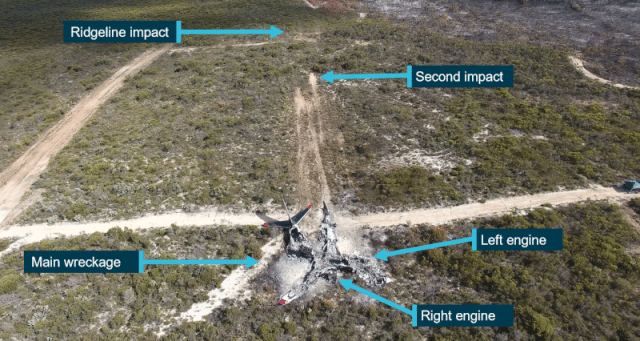

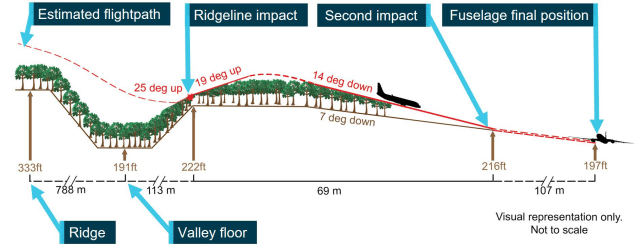

When we last saw Bomber 139, they had just flown into a ridge and subsequently crashed on the high ground. Amazingly, the flight crew were able to walk out of the cockpit of the smashed up plane and were picked up by helicopter.

Fundamentally, this crash was caused by the crew allowing the aircraft to drop to a dangerously low energy state without the crew realizing the danger until it was too late. Low and slow, the Boeing 737 was unable to climb over the rising terrain in the time that it took the engines to spool up.

When we talk about low energy, or in fact about energy at all, we are talking about the power the aircraft has to manoeuvre. It is similar to momentum on a bicycle – if you are pedalling hard as you approach a hill, you’ll have both the speed and power to get to the top. But if you’ve been coasting, you’ll need time to build up both the momentum and the pedal power to make the climb. Similarly, if you are at full thrust and climbing away from terrain, it’s easy to see that if you level out now, you will keep going straight for quite some time even at idle power. The problem is if you are flying straight and level with the power at idle and you try to climb; the aircraft literally does not have the energy to do so without a serious increase in engine thrust. And the important point is that engines take some time to spool up from idle.

Specifically, the Boeing 737-300 engines operating at a high idle setting needed about 7-8 seconds for them to reach go-around thrust after the thrust levers were advanced. That was about two more seconds than they actually had.

But how had a very experienced captain ended up in that situation in the first place?

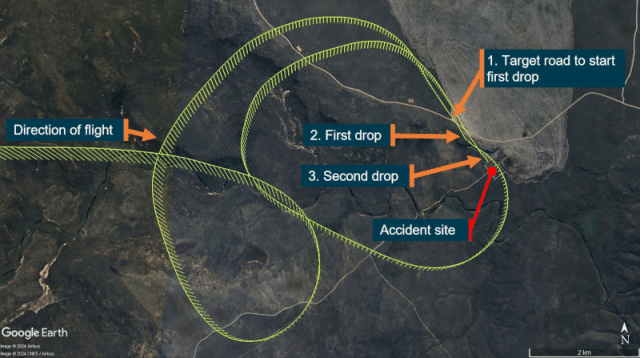

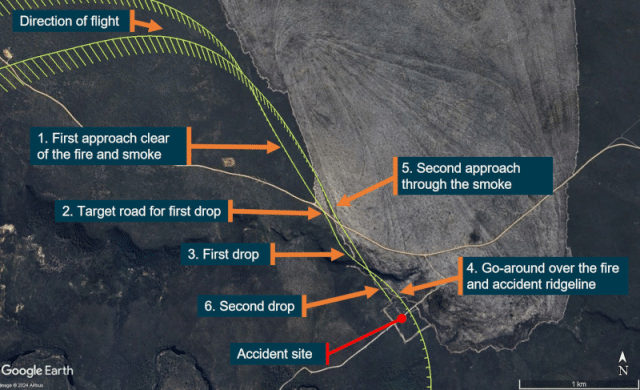

The accident sequence goes right back to when Bomber 139 arrived, when the flight crew turned down the offer from Birddog 123 to fly a Show-Me run. If they had followed Birddog 123 through the proposed run, they would have known about the rising terrain.

Because they were flying a right-hand circuit, the captain, seated on the left and on the outside of the turn, had limited visibility of the drop zone. Visibility was further hindered through the drift smoke. The Birddog pilot, who considered the terrain to be “relatively flat”, inadvertently reinforced the flight crew’s belief that the terrain was falling away. The first officer, in his role of Pilot Monitoring, was looking outside of the aircraft to search for the target through the smoke.

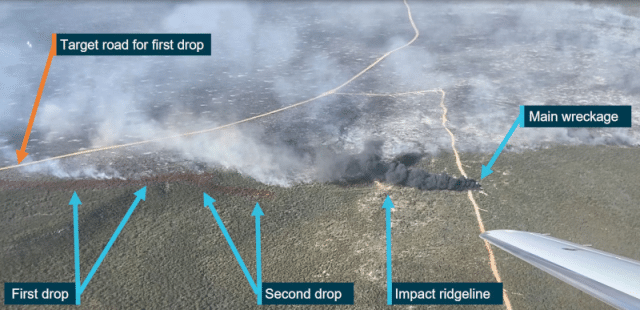

As Bomber 139 descended for its final drop, the crew flew into a landscape that was a textbook example of a dangerous visual trap. It’s known in the aerial firefighting industry as the “hidden hill” illusion, an effect where a consistent carpet of vegetation causes the terrain in the foreground to blend seamlessly into rising ground in the background, completely masking any valley or subsequent ridgeline in between.

The captain, who had taught the dangers of the ‘hidden hill’ illusion as the US National Aerial Firefighting Academy (NAFA) certification, couldn’t perceive the trap unfolding beneath him. He would later describe what he saw from the cockpit: ‘It was hard to see any depth or any descent throughout that at all or the fact that there was a rise on the other side.'”

The combination of idle power, full flaps and their reduced target speed meant that they had very little energy in reserve.

The crew’s expectation was set: they were on a “downhill” drop with no briefed hazards, following the Birddog through smoke toward the target. As they descended, the view from the cockpit was of a continuous, uniform slope. But this view was deceptive. Unseen on the far side of the depression was the accident ridgeline, its elevation masked by the unbroken sea of trees.

The bad visibility combined with the hidden hill illusion meant that neither pilot was aware of the upcoming elevation changes. As an instructor at the US National Aerial Firefighting Academy, he had warned his students about this deceptive visual trap where rising terrain in the distance blends seamlessly with the foreground, masking the true peril until it’s too late. Later, back at the crash site, the captain commented on how difficult it was to perceive the rising ground on the far side of of where they had impacted the ridge.

With their engines at idle for the expected descent, they were flying with low energy, unaware that the ground ahead of them was not falling away, but rising to meet them. Boeing’s analysis of the flight data was that if the terrain had been flat, let alone falling away as they expected, the Boeing probably would have climbed away safely.

It was standard procedure to recalculate the drop speed after a partial drop, lowering the speed to account for the lower weight. But this was not without risk and in this case, it led the crew to target a drop speed that gave them very little safety margin. Worse, neither crew member noticed that the speed was decaying dangerously.

The operator’s Cockpit Resource Management philosophy was that during a drop, Pilot Monitoring announcements should be limited to deviations, rather than confirmations of speeds and heights. The idea is to minimise distractions, so that the Pilot Flying can concentrate on the drop. But without callouts, the Pilot Monitoring isn’t actively tracking and verbalizing the flight path; they’re just watching for something to go wrong. It’s passive surveillance versus active monitoring.

On top of that, first officer didn’t realise that they were low; he did not, in fact, know that there was a minimum drop height at all. Neither the operator nor the Western Australian Government departments had published a minimum retardant drop height for large air tankers. This was possible because each state was writing its own rulebook, allowing for dangerous omissions.

The operator used 150 feet as a “standard target drop height” but this was assumed knowledge, not published in the Standard Operating Procedure (SOP). The crew was operating using profiles common in the US and with their company, but which weren’t documented in the local procedures. Crews relied on word of mouth and assumed standards because the local ones were incomplete.

As a result, the first officer didn’t see any reason to alert the captain as the Boeing dropped below 150 feet. In fact, the first officer thought that 150 feet was the maximum height for a drop, to mitigate the effect of the wind on the retardant.

Although the captain asked the first officer to complete the pre-drop checklist, they never discussed the drop height and neither pilot bothered to set the decision height on their radio altimeters, which would have forced the conversation as to what the target drop height should be. The first officer was allowed to continue in his belief that 150 feet was the maximum and that there was no minimum.

As a result, during the drop, the aircraft dropped to 57 feet, well below the undocumented 150 feet minimum, operating at 110 knots. The low airspeed caused the aircraft to lose energy, causing them to descend further than intended. But the captain was not concerned, based on the performance on the previous drop, the captain was confident that they could quickly recover.

Standard procedure was for the Pilot Flying to advance the thrust levers at the halfway point of the drop, in anticipation of the go-around. The captain did this, but it was a partial load that only took five seconds to release. Nothing happened for the first second, leaving only 1.5 seconds for the engines to spool up for the go around, nothing like the 7-8 seconds that the engines needed.

As with the previous drop, the captain had reduced the thrust to idle for what he thought was a downhill approach and then advanced the thrust levers halfway through the drop. But the previous drop was nine seconds long, leaving 4.5 seconds for the engines to spool up while they were still doing the drop He hadn’t considered that on this drop, only five seconds, he needed to advance the thrust levers at the start of the drop, not halfway through, to achieve the same effect.

This is how Bomber 139 ended up low and slow as the second drop was finished, well below the operator’s standard target drop height and slow enough that they were still descending. This was a very bad situation, hence the captain’s emergency call to focus: “Fly airplane!”

But on top of all that, the terrain was now quickly rising and before they even had time to think, the ridge appeared to come out of nowhere.

From the final report:

During the retardant drop downhill, the aircraft descended significantly below the operator’s standard target drop height and airspeed and entered a high rate of descent with the engines at idle. While the engines were starting to accelerate at completion of the drop, the airspeed and thrust were insufficient to climb above a ridgeline in the exit path, which resulted in the collision with terrain.

Prior to the retardant drop, the aircraft captain (pilot flying) did not detect there was rising terrain in the exit from the drop, which likely contributed to the captain allowing the aircraft to enter a low energy state during the drop.

After arrival at the fireground, the aircraft captain (pilot flying) declined a ‘Show-Me’ run and was briefed by the Birddog pilot that it would be a downhill drop. Bomber 139 then conducted a go-around from the high ground after the first drop and was led to the target through the smoke on the second drop. These factors likely contributed to the captain not expecting or detecting the rising terrain in the exit path.

The co-pilot (pilot monitoring) did not identify and announce any deviations during the retardant drop, which could have alerted the aircraft captain (pilot flying) to the low-energy state of the aircraft when it descended below the target drop height with the engines at idle.

The flight crew did not brief a target retardant drop height and, contrary to published standard operating procedures, did not set it as a decision height reference on the radio altimeter. Subsequently, the co-pilot (pilot monitoring), who did not believe there was a minimum drop height, did not alert the aircraft captain (pilot flying) to the low-energy state of the aircraft.

The investigation concluded that the key contributing factors were the low energy state, recalculation of the drop speed after a partial load drop, lack of a published minimum drop height and reactive pilot monitoring instead of pro-active call outs.

Beyond the direct causes, the report highlights wider industry issues: inconsistent visual standards, the hidden hill visual illusion and tactical flight profiles.

After the accident, the operator proactively increased their minimum drop height to 200 feet and prohibited the lowering of drop speeds following partial load drops. The Western Australian government offices have also updated their procedures for a minimum 200-feet drop height for Large Air Tankers. The Australasian Fire and Emergency Services Authorities Council is working on a set of standard operating procedures for air tankers on a national level.

The ATSB is conducting a review of aviation safety aspects of aerial firefighting in Australia, considering the systemic issues within aerial fire fighting activities as operations become more complex. It will be interesting to see what the final report has to say about whether this was an isolated “perfect storm” or part of a larger problem.

A while ago the RNZAF lost an A4-K to this “hidden hill” illusion. Unlike Bomber 139 the Skyhawk was flying fast at low level, preparing to pop up to intercept a pair coming by at high altitude. The aircraft seems to have been pulling about 8G at impact but, sadly, it wasn’t enough.

The pilot was a friend of mine – for a while we were co – owners of a Tiger Moth. I decided not to take part in the investigation.

Hi Sylvia, love your write-ups, always insightful.

As a non pilot I was wondering why they don’t run the engines with a little more power and use the spoilers to create drag and balance the performance?

Keep up the good work.

Does the 737-300 have spoilers? Wikipedia says the concept was first implemented back in 1948, but I have the impression they weren’t that common on airplanes (as opposed to gliders) when the -300 was in production — and that they were used more to completely destroy lift after landing than to adjust drag during descent. (“Speed brakes” sometimes do the latter on more recent aircraft.)

They were flying with full flaps, which already adds considerable drag.

The 737-300 classic does have wing spoilers; only the outboard spoilers can be used in flight.

It wouldn’t have made much of a difference, because their main problem was lack of altitude and excessive descent rate. When the aircraft is “falling”, it needs to expend energy to get to “hover”, and then, with more energy, to climb—unless, of course, speed can be traded for altitude: they did that to barely clear the ridgeline, but didn’t have enough speed left to keep flying after that.

So the engines could’ve spun a little faster if the crew had kept the altitude better, and then they’d also have had more energy to work with. And they surely would have if they’d been more aware of the terrain.

The spoilers I’ve seen in operation move very quickly, where flaps move relatively slowly; I was taught that the first several degrees of flaps add mostly lift (hence the use of partial flaps in short-field takeoffs), where the last degrees add mostly drag. ISTM possible that some combination of spoilers, more power, and an intermediate flap setting might have given them a better chance of getting out of a bad situation quickly, because they could have kept the added lift of partial flaps while needing less time to reduce drag and get to full power. HOWEVER: I don’t know the expected behavior of a large airplane (as opposed to a Cessna 152 or 172) in that configuration, and I wouldn’t be surprised if that configuration had never been tested for flying (as opposed to landing — or had been tested but not documented) which means the pilots couldn’t have been expected to try it.

That being said, you’re certainly right that having better information about the terrain would have helped. (The report doesn’t say whether anyone asked the captain WHY he declined the Show-Me run; perhaps he was over-confident about his hours, especially his 5500 firefighting hours?) So would having clearly established specifications for drop altitudes. (I’m reminded of https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TWA_Flight_514, in which there was similar confusion about ceiling vs floor of a flight path.)

A side note: the “hidden-hill” illusion sounds like the intent of https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ha-ha — but this is a natural phenomenon rather than an intentional trap, and nobody’s laughing.