ATC and the Pilot Who Turned Back

Last week we looked at a general aviation crash in which the pilot reported a Mayday as a result of an engine failure. Eight minutes later, the pilot crashed into a forest near Colbert, Oklahoma.

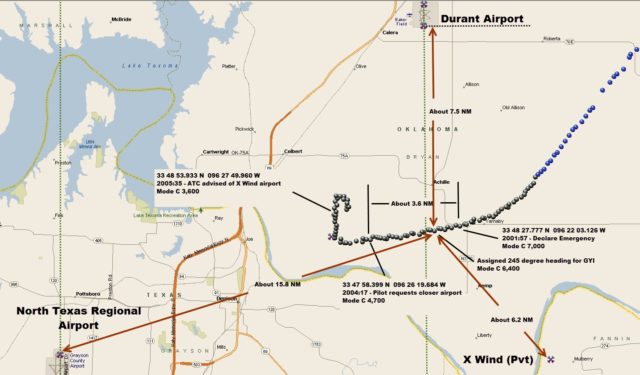

Today, I want to focus on what happened with the air traffic control centre who advised the pilot. The pilot was originally told that North Texas Regional Airport (GYI) was at his 12 o’clock and about 15 miles, and he was given vectors to fly there. Then the pilot asked for something closer and was advised that Durant was at his 3 to 4 o’clock and 10 miles.

A clear issue was that the controller was not very clear or confident about where the nearest airfield was and effectively offered the pilot a number of choices. This became critical when the controller mentioned a private airstrip close to the stricken aircraft and then dismissed it as too far.

Controller: They’re showing a private field about 1 mile behind you called Cross Winds.

Pilot: Wish I knew where that was.

The controller gave the pilot the airport configuration for Durant and the pilot said something about the private strip. The controller asked him to say again.

Pilot: Where’s that private strip?

Controller: It’s not close enough for you to get to. There is GYI at your 2 to 3 o’clock 10 miles and Durant is at your 6 to 7 o’clock and 10 miles.

The pilot never responded again.

The Beechcraft had turned back, presumably to find the private airfield. It crash landed into a forested area; both the pilot and his wife were killed in the impact.

You can read the initial post here: The Pilot Turned Back: Engine Failure Leads to Fatal Crash

An internal investigation into this fatal accident was launched and it is particularly interesting to me as it gives us some insight into the communications within the control centre and why the advice offered to the pilot appears so confused.

Fort Worth Air Traffic Control Center were contacted by the pilot of a Beechcraft Bonanza who declared an emergency, having lost engine power. He was at just over 8,000 feet and descending. He requested help to get to an airport right away.

The controller at Fort Worth Air Traffic Control Center who was working the radar positions was a developmental controller, that is, still under instruction to become a certified professional controller. She was working a ten-hour shift covering three sectors, which were her last radar positions to train on. She’d been on the position for almost two hours when the incident started. At the same time, there was a ‘rebank’ or arrival push, so the sector suddenly became more complex. Because of the variation of traffic, it is common to combine and decombine the sectors throughout the day, based on load.

From an FAA standpoint, traffic counts above 18 aircraft are considered a reason for workload concern. That day at 15:00, the developmental controller was handling twenty four aircraft. The controller in charge had already decided to split the combined sector into individual sectors and instructed the Sector 37 controller to do so. The Sector 37 controller was surprised that they were combined, as usually by that time on a Sunday the sectors were always split.

Her instructor had also noticed the traffic increasing but he wasn’t concerned as the controller in charge had already said that he was going to split the combined sectors.

Decombining the sectors normally took three to five minutes. He set everything up and attempted to split the positions, but the radar controller training team said that they were too busy.

It was at this point that the accident pilot first attempted to make contact. His transmission was “stepped on”, that is, blocked by another person trasmitting at the same time. The developmental controller acknowledged the call and told the pilot to go ahead. He immediately declared an emergency.

We’ve lost engine power and we need…to get to an airport right away.

The developmental controller and her instructor quickly discussed his options and agreed that the aircraft should go straight ahead to North Texas Regional, about twelve miles away. The instructor remembers noticing Durant as about the same distance from the aircraft but North Texas Regional had a control tower, emergency services and it would be easier to for the pilot to get vectors.

The developmental controller advised the pilot that North Texas Regional was at the pilot’s 12 o’clock and about 15 miles. The controller thought that North Texas Regional was a good choice because it was straight ahead and she believed that any significant turn would result in altitude loss. She wasn’t sure why she hadn’t recommended Durant (DUA) from the start. Her instructor also neglected to notice that this was the closer airport at the time of that first call. He believed that flying straight and level was preferred and couldn’t remember where he’d received the training that turns should be avoided.

The controller in charge walked over to her position to monitor the situation. He assigned another controller to the radar associate position to assist the developmental controller by accepting hand-offs from adjacent sectors but asking them to delay switching the aircraft to their frequency to allow the controller time time to deal with the emergency. He doesn’t remember anyone asking for the number of persons on board or the aircraft fuel or, when it came to it, any additional information about the Bonanza.

After the pilot asked for something closer, the controller gave him the details of Durant. The pilot asked if it was a left turn towards Durant and the controller corrected him, saying it was a right turn.

The Sector 37 controller who had been waiting to split the sectors heard the pilot say that he had lost power and that he needed an airport. Concerned that the pilot couldn’t make either North Texas Regional or Durant, the Section 37 controller started searching the VFR sectional map. He remembers that he stood up on the console and put his reading glasses on, but the differences in scale made it difficult to determine the position of the aircraft on the VFR map. The instructor joined him to look at the VFR sectional map.

The Front Line Manager heard the commotion at the controller’s position and noticed that there were three people, including the controller in charge, offering advice. He thought it would probably be easier for the Bonanza not to make any hard turns (towards Durant) but he wasn’t sure if any turn would be required for the pilot to continue to North Texas Regional Airport. Then his airspace became busy and he stopped paying attention. He thought the aircraft had landed safely and did not find out that the plane had crashed until he was relieved of his position.

The Radar Associate was on break when the emergency call came in. When he came back, he heard someone say that a pilot had declared an emergency. He didn’t think the sector was that busy but sat down on the radar associate position to help as needed. He felt that the recommendation for North Texas Regional Airport was reasonable as the airport was directly in front of the aircraft.

The Sector 37 controller, the controller in charge and the instructor continued to search the VFR sectional map on the overhead, trying to find an airport. The radar display did not have major features such as rivers and highways, so it was difficult to correlate the aircraft target symbol on the radar display with the VFR sectional charge.

Meanwhile, the developmental controller was speaking to the pilot. She doesn’t remember which of them told her about Crosswind Airport, a private field which was not on her radar. Someone, again she doesn’t remember who, said the private field was about a mile behind the aircraft.

She told the pilot about the private field. But then when she asked the others where it was, she got no response. Eventually someone told her that it was too far away.

The controller passed this on to the pilot and told him again about Durant. This was when the pilot decided to turn around, apparently hoping to try to find the private strip on his own.

The problem was that Crosswind airport was actually ten miles behind the pilot, not one mile. Someone had misread the VFR sectional map.

The Radar Associate remembers Crosswind airport being brought up as a possibility. He didn’t know much about it and said that he’d seen maybe three airplanes land there in five years. In his recollection, it was the Sector 37 controller who brought it up first. He couldn’t recall who said it was only a mile away or who later said that it was too far.

The Sector 37 controller remembers the discussion of the private airport but not who relayed the information to the developmental controller. He said that if it was in range, he certainly would have mentioned it as an option but didn’t know who came up with the one mile distance or how that was determined. He said that he would never attempt to inform the pilot of the location with that much precision. Possibly, he said, the training team misinterpreted some of the details that they overheard from those standing at the map.

He didn’t hear the pilot asking about Crosswind and said he was definitely not the person who said that it was too far away.

The instructor also remembered the Section 37 controller as the one who suggested the Crosswind airport and also thought it was him who estimated the field as a mile behind the aircraft in distress. He agreed that it was very difficult to correlate the radar to the VFR sectional map and that it would have been much easier with geographic features on the radar display.

His recollection was that he and the Section 37 controller worked out that the initial estimate was inaccurate and that Crosswind airport was too far away. Durant was clearly the best option. He also noticed that the traffic had increased but it seemed a bad idea to decombine the sector given the volume of traffic and the emergency. He had not realized that the traffic volume had exceeded the normal level of 18 aircraft, although that level had already been exceeded before the distress call. The instructor said there was nothing more that they could have done for the pilot and he would not necessarily change anything they had done.

The Operations Manager in Charge was preparing for a meeting when the controller in charge told him about the emergency. Later, he reviewed a replay of the event, he was alarmed that the two sectors were combined with that level of traffic.

In retrospect, the Sector 37 controller said that he should have isolated the emergency aircraft from the others so that an exclusive service could have been provided to the pilot. However, he did not believe that he ever suggested the Crosswind airport to the controller talking to the pilot.

The Fort Worth Quality Control Manager saw the incident on the news and phoned in. He was told that everything was under control. When the quality control staff came in on Monday the 27th of July, they gathered the audio recordings to make transcripts. The QC manager was immediately concerned both that the sectors were combined and that the information provided to the Bonanza pilot did not meet his expectations. He had been of the impression that the developmental controller was close to certification and did not know that she was inexperienced on those sectors which had been combined. He felt that the controller had cleared the aircraft to one airport and then to a second airport before diverting the aircraft to a private strip without providing additional information.

When the Quality Control Manager later asked the controllers involved about the decision to clear the aircraft to North Texas Regional airport, they responded that ‘you give them the closest airport straight in front of them.” He could not find that guidance as part of the Fort Worth training and came to the conclusion that it may have been learned from previous facilities.

The Central Service Area (CSA) Quality Control Group Manager was notified by Regional Operations Center that the aircraft crashed and became involved in the accident review. He said that the the biggest roadblocks to his efforts are a lack of clear expectations of what quality control looked like. There are nine specialists covering the entire central United States and they are struggling to keep up. The turnover at such facilities is high and often as soon as a facility QC person was “up to speed” on quality control, they would move on and the process at their facility would need to start over.

In the end, what should have been a non-event turned into a tragic crash. The pilot starved his engine of fuel and then never followed the emergency checklist prompt to check the fuel selector, which would have solved the problem. The pilot also decided to turn around without any clear details of the “private strip” and failed to land on any of the nearby fields, instead crashing into a wooded area.

However, it’s also important to think about the fact that when he first declared an emergency, he was 15.8 nautical miles from North Texas Regional, 7.5 nautical miles from Durant and 6.2 nautical miles from the Crosswind private airstrip. Flying at best glide, he should have been able to travel 17 nautical miles. The pilot failed to commit but it is also true that the air traffic control advice given him that day failed to support him. It is critical that all systems, not just those in the air, be investigated and analysed in order to learn how to do better in the future.

You can read the full report, listed under Air Traffic Control Factual, in the NTSB docket for the investigation.

A litany of errors and coincidences. The best advice, of course, would have been to tell the pilot to keep flying straight ahead.

An altitude of 8000 feet? I remember once coming into Heathrow at night with the Corvette (a 14 passenger light jet transport). It was a clear, windless night. At 10.000 feet ATC told us that we were “clear to land” at any runway we liked. I forgot which one we picked, but we decided to turn it into a practice. We closed the taps and made what amounted to a virtual “deadstick” approach and landing. Plenty of time and gllding distance.

What is the best speed for the Bonanza? Let’s assume 120 KIAS. I reckon that the descent rate, the loss of altitude over time, would not be much more than 800 ft/min.

Which would have resulted in 10 minutes before hitting the ground – assuming 8000 ft AGL.So in that scenario, the range would have been 15, maybe 20 miles. But as soon as the pilot makes a sharp change of direction, the descent becomes much more steep, a lot of precious altitude lost plus an increasing disorientation and panic.

What is that famous saying again?

In aviation, in case of an emergency nothing is as useless as the sky above you, the runway behind you and the fuel you did not put in the tanks..

A sad litany of errors, errors of judgment and confusion.

The conflicting and confusing ATC advice, instead of being helpful and no matter how well intended, must have had a direct impact on the sequence of events that led to this fatal crash.

I don’t know the Bonanza, but let us assume that the optimum gliding speed is 120 kts. And let us assume that it would descend about 700-800 ft./minute.

The aircraft was at 8000 feet, was that AGL? If correct, it would have been able to stay aloft for the better part of 10 minutes.

And, provided it would have been flying straight ahead, that meant a potential distance of better than 15 miles. In other words: North Texas should have been nicely within gliding range.

The offering of other airports to a pilot in distress, in an increasing state of disorientation, may well have been the final straw. It is well known that turning (without engine power) will cause a substantial loss of altitude and, if the pilot is attempting to “stretch” the glide by reducing speed, also will increase the risk of stalling.

It seems that when making the turn to a nearer landing place, the pilot became confused and disorientated. His flying must have deteriorated and instead of making a survivable crash-landing on more or less open terrain, he crashed into trees and killed himself and his wife.

There is an old saying in aviation that still is valid:

In an emergency situation, nothing is as useless as the air above you, the runway behind you and the fuel that is not in the tanks

Rudy — those numbers are close to what I recall for the C172, but possibly a bit optimistic; OTOH, a retractable might do a bit better than my 5 miles per 3000 feet. I had to know the number, because the standard rule is not to take a single-engine plane further out over water than it can glide back — but some inattentive air traffic controller once tried to route me from Islip direct to Atlantic city, up to ~35 miles from the nearest coastline.

But this strikes me as what a friend calls a yak-shaving (a step beyond a goat-roping); nobody seems to have taken command and said “The exercise is over; we’ve got an emergency”, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the authority (and the personnel to re-divide the zones) weren’t there. It’s true this mess took a cascade of errors, not unlike most crashes that can be blamed entirely on the flying elements, but ISTM that circumstances have become more unfavorable. The controllers’ union made the incredible mistake of endorsing Reagan in 1980 and then believing he wouldn’t act when they struck; he fired them all, and I’m not sure ATC in the US has yet recovered. (Recovering from the same approach to a police strike in my hometown (Boston) took over two generations.) I never got the feeling when I was flying (5-8 years before the strike) that ATC was trivializing my flight because I was a lot smaller and slower than the scheduled airlines, but I’m less unhappy not have kept flying since; solo pilots have far less room for error than a crew, and it sounds like ATC know less about small equipment than would be desirable.

Chip,

I can only agree with all you just wrote, but the situation in Europe is probably different from that in the USA. There is a lot less free airspace, but that also means that ATC are often more used to light aircraft mixing it with the big boys (and girls) in their big toys. I have had some hilarious moments when ATC were dealing with inexperienced pilots, making sure that they would not come to any harm, but at the same time making them painfully aware of their failings. But that would be something for another day (and comment).

About gliding distance: During training, studying for the CPL I think, a question came up:

A Piper Cub and a jet fighter (F104) have an engine failure at 10.000 feet.

Assuming that the fighter pilot does not bail out, which aircraft will cover the greater distance before hitting the deck?

Surprisingly, the fighter covered a far greater distance but when it crashed the Cub still had a few minutes up in he air.

Another (actual exam) question was: A world war 2 bomber loses power over the channel on its way back from a raid over Germany (after all, I did my CPL in 1969). It was hit by flack and did not make it to it’s target, so it still has all its ordnance on board.

What will be the best course of action to extend the gliding range:

1. Drop the bombs and as much weight as they can over the channel? or

2. Keep it all on board?

Surprisingly, the RANGE increased with the weight still on board.

So, with that in mind I would not be surprised to find that the Bonanza, as you already mentioned, with less drag from wheels and wing struts, would actually cover the same or possibly more distance.

The 172 pilot would have more TIME to consider his options.

That’s a fascinating set of results. I wonder how old they are; I used to know someone who flew bombers out of England in WWII and would love to know whether he was taught this. (He learned to fly before learning to drive, and said he had to conquer the urge to yank back on the steering wheel at crowded intersections.)

It sounds like European ATC may have had more time than US ATC to deal with low-and-slow even before Reagan damaged the system.