Aircraft Collides with Lorry on Henstridge Approach

On the 2nd of March, 2023, a Vans RV-9A struck a vehicle while coming into land at Henstridge Airfield.

The Vans RV-9A is a Van’s Aircraft kit plane, a kit for enthusiasts to build an aircraft themselves. The RV-9 is a two-seater low-wing aircraft; the original model is a tail dragger, but the RV-9A has a nose wheel. It’s an efficient and versatile single-engine aircraft.

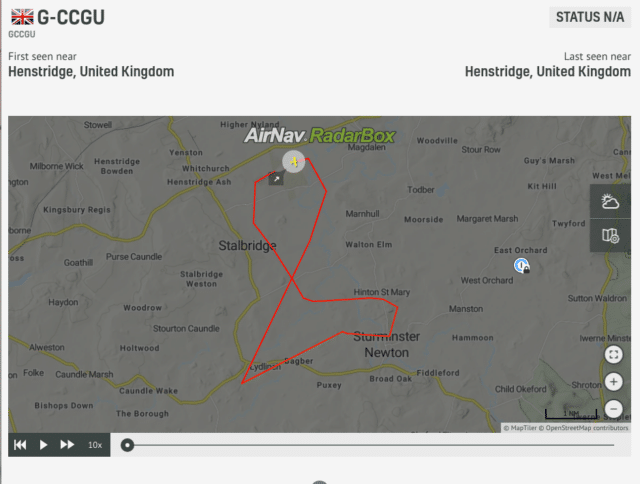

This one was registered in the UK as G-CCGU and is based at Henstridge Airfield.

Henstridge has an amazing history. It was designed in 1941 as a five-runway naval airfield to offer Deck Landing Training. In 1943, it was finished and commissioned as the HMS Dipper, with this adorable badge.

One of the runways had an aircraft carrier deck set in the middle with an arrestor wire system set up so that the naval pilots could practice landing on the deck. Seafires, Spitfires and Typhoons operated out of the airfield until the end of the war. Although the airport closed in 1949, it was soon reopened and the “Dummy Deck” was used for a few years by RNAS Yeovilton, including for Night Deck Landing Practise in 1954, which apparently was not very popular with the local residents.

However, the runways designed for WWII were not very suited to the jet fighters and by 1958 the land had been sold for to local farmers. One of those farmers had an aircraft and used the runways to hold fly-ins during the 1970s. Over time, the number of aircraft at the airport grew to 16. The site is now run as Henstridge Airfield Ltd.

Only one of the original five runways remains, 06/24 (at the time, 07/25), with the concrete “Dummy Deck” still visible in its middle.

This isn’t actually relevant to the incident, I just thought it was interesting.

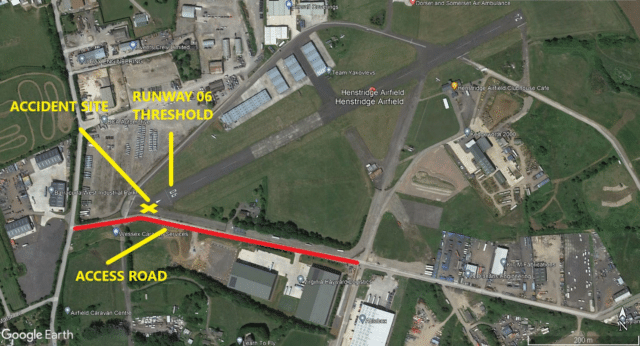

Today, Henstridge is an unlicensed airport. There is a road on the south side of the airport which leads to an industrial site. The road has a significant amount of traffic, including Heavy Goods Vehicles (HGVs: an articulated lorry/truck). The road runs right up to the start of the runway before turning. As a result, the runway has a displaced threshold; the threshold is marked as 22 meters further along the runway. That means that, for aircraft coming in from the south, the first 22 meters of the runway are considered unusable. The full runway is available for take-offs and for landing from the opposite direction; the runway is only shortened for approaches from the south in order to keep the low-flying aircraft clear of the traffic.

On the 2nd of March, the pilot and a passenger departed Henstridge Airfield at noon for a short local flight in preparation for a longer flight to Dunkeswell planned for the afternoon.

The flight was uneventful and as they returned to Henstridge, the pilot entered the circuit to land on runway 06.

The pilot has been flying at Henstridge for 17 years and was aware of the displaced threshold and the traffic. He recalled that the aircraft was at 500 feet above ground level as he turned into the final approach. He descended towards the runway as usual, which is a 3° slope towards the displaced threshold. Everything seemed normal. He glanced at the road for traffic; the road seemed to be clear.

Just before they touched down, the pilot suddenly saw an HGV to his right, much too close. The HGV had crossed their approach path from left to right underneath the aircraft, hidden by the low wings. The pilot saw the RV-9A’s right wingtip struck the rear of the trailer. Then it all went black.

Slowly, the pilot realised they were upside down on the ground, trapped inside the cockpit with the canopy smashed around him. He and the passenger were held in place by their seat harnesses. The aircraft’s roll bar had stopped the cockpit from collapsing around them.

A car driving behind the HGV stopped and ran to the scene. They pulled away pieces of the canopy perspex until they’d cleared a gap big enough to pull the pilot and the passenger out of the cockpit. Henstridge is home to an Air Ambulance base; their staff raced over to offer medical assistance. Emergency services arrived at the scene soon after and took the pilot and the passenger to the hospital.

Photographer Neil Randell was there on the day of the accident and told me that he’d just gone to the Club House to meet a friend, or else he would have been about 75 feet away from the crash site. He explained that the Dorset and Somerset Air Ambulance Helicopter is based at Henstridge and were able to get their ground units to the scene very quickly.

The road that the HGV was travelling along has a left turn right at the closest point to runway 06. It was exactly here that the aircraft’s wing struck the HGV’s trailer.

The AAIB investigation focused on this point. A licensed airfield in the UK has specific requirements for obstacle clearance.

Henstridge Airfield is unlicensed, thus the obstacle clearance rules don’t apply, but it is useful to look at the requirements anyway. At 70 metres from the threshold, where the accident occurred, anything over two metres tall would penetrate the protected area. A road is considered to be an obstacle extending to 4.8 meters from the crown of the road. Thus, at the closest point to the runway, any traffic on the road presented an obvious obstacle penetrating the protected area.

The pilot could not see the HGV as it crossed beneath the aircraft and the Vans RV-9A continued to descend until the wing hit the trailer. A standard approach path of 3° for landing at the threshold of runway 06 would be 3.7 metres above the ground as it crossed the road.

Although the report doesn’t specify, an HGV such as the one on the road that day ranges from 3.5 metres to 4.2 meters high.

It had taken years for crash to occur but based on those measurements, it seems inevitable that at some point, an aircraft and a vehicle would occupy that same space: there simply wasn’t enough clearance.

The aircraft struck the top of the HGV and was therefore approximately 4 m above ground and commensurate with a 3° approach. The road converged with the runway centreline at a shallow angle and this, combined with the low wing configuration of the aircraft, meant it was unlikely the pilot would have been able to see the HGV during the approach.

The airfield operator moved the threshold for runway 06, displacing it by an additional 100 metres. This means that the road is now 170 metres from the threshold and aircraft coming in at a 3° path would now cross the road at 9 metres, safely away from the traffic.

The pilot had only minor injuries. The passenger required surgery for a broken wrist but was released from hospital a few days later.

The damage to the aircraft was substantial: both the wings, rudder, engine propeller, engine cowling, engine mounting and firewall had taken damage and the canopy was destroyed. The report makes no further mention of the HGV.

I’d like to know how the lorry driver explained the damage to their boss. “You got hit by a plane?!?”

I’m sorry, but my first thought on seeing the headline was “If you land right at the end of the [runway] your wheels will rip the tops off the Midland Red buses on the Coventry Road — which is not approved.” (I hope nobody was cold enough to share that with this pilot.)

My next thought was “Who did (or didn’t do) the math?” 22 meters is so obviously not enough for a standard descent; was it done so long ago that trucks were lower? (I was also wondering whether it was a rounder number in English measure, but it’s 72 feet — not even rounded up, although that wouldn’t have been enough for safety.)

The field owner is lucky he’s in the U.K.; in the U.S. the pilot would probably find a contingency lawyer willing to sue, which would probably cost the field owner enough in legal fees that he’d lose the field (which would probably be converted to other uses) even if he won the case. This way at least the field is still in operation; the plane owner, OTOH, is hosed, apparently through no fault of his own, which is a pity.