Air India 171 Crash Triggered by Fuel Cutoff

On the 12th of June 2025, a Boeing 787-8, registered in India as VT-ANB, was operating as flight Air India 171 for a passenger flight from Ahmedabad to London Gatwick. The Boeing Dreamliner crashed shortly after take off, killing all of the crew, 229 passengers and 19 people on the ground. One passenger survived with serious injuries. A further 67 on the ground suffered serious injuries.

The day after, I wrote about the basic details and highlighted two credible theories for what had happened: either the aircraft was badly misconfigured or that both engines failed. At the time, the most compelling reason I could think for both engines failing was contaminated fuel, although it seemed unlikely as that should have affected all aircraft refuelling at the airport that day. I concluded that there could be a further “something else” that we were missing because the details so far didn’t make sense.

That sadly has proven to be the case and it doesn’t look good. I’m going to focus on exactly the sequence of events as stated in the preliminary report.

The aircraft arrived from Delhi flown under different crew. There were no known defects with the aircraft and the weight and balance were within normal operating limits.

The captain held an ATPL with over 15,000 hours experience across a range of aircraft, with 8,600 on type. The first officer held a CPL with 3,400 hours of which 1,128 were on type. Neither had flown over the past 24 hours. They had arrived at Ahmedabad the previous day in order to operate flight Air India 171 that day. Both had adequate rest periods. Both pilots passed their preflight Breath Analyser test, which is standard procedure for all flight crew at Air India.

The first officer was the Pilot Flying with the captain as Pilot Monitoring.

At 07:43 UTC (12:43 local time) the flight crew contacted ATC for pushback, which was approved, followed by the aircraft starting up. ATC asked if the aircraft required the full length of the runway and the crew confirmed that they did. At 08:07:33, the aircraft was cleared for take-off.

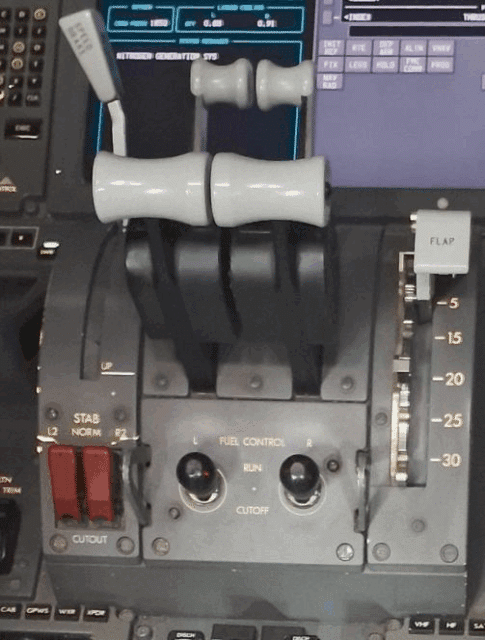

The aircraft accelerated along the runway and reached V1, the take-off decision speed, of 155 knots normally. The aircraft lifted off at 08:08:39 UTC. In the air, the aircraft reached 180 knots indicated airspeed at 08:08:42, at which point the fuel cutoff switches transitioned from the RUN position to the CUTOFF position.

The report uses the word transition, because the flight data only tells us that the position changed. However, a critical piece of information is that there was a one second gap: one switch was set to CUTOFF and then, a second later, the other.

This video posted to Reddit shows the guards around the two fuel cut off switches in a Boeing Dreamliner. What one can see in the video, which is confirmed in the report, is that to change the switch from the RUN position to CUTOFF position, you have to pull each switch out and then down. There are guards either side. The point is that it is not possible to accidentally knock these switches out of position.

So, both switches moved from RUN to CUTOFF, one after the other. Both engines began to lose power as a result of the fuel being cut off, that is, the report is clear that this was a direct cause and effect.

The phrasing of the conversation in the cockpit is important; here’s what the report says:

In the cockpit voice recording, one of the pilots is heard asking the other why did he cutoff. The other pilot responded that he did not do so.

The cockpit voice recording analysis would include which microphone picked up the voices: on the left or on the right. Thus, it is absolutely known which pilot spoke. The investigators made a clear choice not to release the exact wording or to specify which pilot asked the question.

The report confirms that the Ram Air Turbine deployed during the initial climb, as many had observed from the CCTV footage. This confirms that the engines lost power, causing the RAT to deploy.

The aircraft began losing altitude before making it past the airport perimeter wall.

At 08:08:52, the fuel cutoff switch for the #1 engine transitioned from CUTOFF to RUN. The switch for the #2 engine transitioned to RUN a few seconds later. This initiates a “re-light and thrust recovery sequence”, that is, the engines should automatically restart and begin producing thrust again.

In both cases, the engine relighting sequence started; however, this is a slow process. The #1 engine was in the process of spooling up. The #2 engine restarted but was not able to spool up and recover thrust. Effectively, both engines responded exactly as one would expect to having the fuel cut off and restored. The problem was that there wasn’t enough time for both engines to spool back up. Had the issue occurred just a few minutes later, after the aircraft had gained altitude, the engines would have had enough time to restart and produce thrust.

One of the pilots declared an emergency at 08:09:05, calling MAYDAY MAYDAY MAYDAY.

The air traffic controller asked for more information but did not receive a response.

The Flight Data Recorder stopped recording data six seconds after the MAYDAY call, at 08:09:11.

The report documents the wreckage, mostly confirming what we already knew. The Dreamliner crashed into multiple buildings and broke into pieces before catching fire. The flap handle was found “firmly seated in the 5-degree flap position, consistent with a normal takeoff flap setting.”

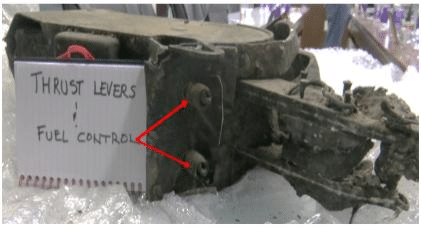

Both fuel control switches were in the RUN position. The engine thrust levers were found set to near IDLE but according to the flight data recorder, both remained set to take-off thrust until the crash, so it’s likely that the levers shifted in impact.

Basically, the wreckage analysis so far underscores the fact that the crew attempted to restore fuel flow to both engines before losing control of the rapidly descending aircraft.

Based on initial investigation of the wreckage, there was no fault with the aircraft. The report notes explicitly that there are no recommended actions related to the Boeing 787-8 or the General Electric engines.

The report also referenced Special Airworthiness Information Bulletin NM-18-33, which has been the cause of much speculation. This 2018 bulletin was in response to a number of Boeing aircraft which were delivered from the factory with faulty fuel switches that could be moved too easily. This was not considered to require an airworthiness directive requiring mandatory inspections.

Air India did not inspect the switches of their fleet and were not required to do so. More pertinently, no one had reported any issues with the fuel switches on the accident aircraft after the throttle control module was replaced in 2023.

The important point here is that there are no reported instances where the switches moved themselves. It is possible that this fault had been on the aircraft without comment for two years. If this were the case, it is still clear that a person moved those switches one after the other; however, it would add weight to the idea that cutting off the fuel was not deliberate.

The logistics of the cockpit mean that the Pilot Monitoring was better positioned to move the switches without it being immediately noticed. The Pilot Flying, focused on the take-off, might not immediately notice the movement. The reverse, where the Pilot Flying moved the switches, would be more noticeable. During take off, with both hands on the controls, any such movement would be immediately attract attention, especially as the Pilot Monitoring should be scanning the instruments and not concentrating on any single spot.

The ten seconds between the switches being moved and the question being asked seems relevant. Assuming that the pilot asking the question was not the pilot who moved the switches, then it seems likely to have been a reaction to the engines spooling down followed by a glance towards the switches to see that they were inexplicably set to the CUT OFF position. But these are now logical guesses; we don’t know who spoke, we don’t know what caused them to speak, and we don’t have any way to interpret the response.

The preliminary report makes it clear that the investigating team have additional evidence to review, including the postmortem reports and statements from witnesses and the surviving passenger. Maybe they will find something that can shed more light on what happened in the cockpit.

It could easily be impossible for the investigation to prove who moved the switches, as they are centrally located so that both pilots have access. What we know: someone moved both fuel switches to the cut-off position. We don’t know who did this. We do not know if it was a deliberate action or a fatal mistake. More importantly, it may not be possible to ever know what the intent was.

Would it be normal to retract the gear at about the time the fuel cutoff switches transitioned – that is, a few seconds after getting off the ground or would it usually happen a little later?

Normally, the pilot monitoring (here, the captain) would call out “positive climb” at around 30-50 feet; the pilot flying would say “gear up” and the PM would then operate the gear lever. So, yes, right about then.

There’s a theory that the PM might have been distracted, feeling “takeoff is over” and then, instead of making the call, switched the engines off like he would do when shutting down the aircraft after a flight, on “muscle memory” while thinking about something else and not being aware of it. It’s called an “action slip”. You can read more about it at https://safetyfirst.airbus.com/cockpit-control-confusion/ .

Sylvia recently blogged about a slip like that in “Hand on Thrust, Brain on Autopilot” at https://fearoflanding.com/accidents/accident-reports/hand-on-thrust-brain-on-autopilot/ .

Or maybe one of the pilots did it intentionally. We don’t know at this point.

Exactly my thought, too – that the PM intended to retract the gear but, through a major brain fart, switched off the fuel instead.

But if that was the case it would be frustrating that the preliminary report didn’t mention the relevant callouts and the synchronisation of the cutoff switch transition with them. Also that they don’t remark on the position of the gear throughout the whole sequence. Of course, if the crew recognised there was a problem before they’d normally raise the gear it’d be quite understandable that its operation would not be a priority for them.

And, yes, of course there’s the darker possibility.

The report does mention that the landing gear lever was found in the “down” position, and the gear impacted the buildings, so it was apparently never retracted. The main gear bogeys simply dropped down under their own weight when hydraulic pressure was lost due to the engines shutting down. None of this is surprising, it fits the timeline.

Right, but the report doesn’t mention whether the “positive rate of climb”/“gear up” call outs happened or not.

If, as your first reply indicates, those would normally happen very early in the climb, at least a few seconds before the crew recognised that something was amiss, yet the gear level was in the down position then omission of information on the call outs in the report is a bit surprising.

It is only a preliminary report but they must know this information and they’ve given other similar information in some detail.

To ur point that the pilot monitoring (a certified trainer) made a switch pig and cutoff fuel instead of raising the undercarriage – (1) the undercarraige raising lever and fuel cut off move in opposite directions so unlikely and (2) he would do it once, not do it twice wherein both engines were cut off

Pradeep Arora, please read the background material I linked. This is not about the pilot flipping the wrong switch thinking it’s the right switch. This is about mixing up the action itself, like being distracted and putting the butter in the microwave instead of the fridge, because “put in the fridge” and “put in the microwave” are both routine actions our brain can do for us without conscious thought. With action slips, the mix-up occurs at this action level.

Pradeep Arora: “…move in opposite directions so unlikely…”

Every day quite a few airliners take off. Generally speaking, not many of them immediately plunge into the nearest available medical training institution so any chain of events leading them to do so is, almost by definition, unlikely.

Anyway, as Mendel says, any mistake would likely have been made at a higher level of abstraction than the actual manipulation of the controls.

I didn’t know the captain (PM) was a trainer. If anything, I’d think that that would make it more, rather than less, likely they’d do something weird as trainers are used to setting up in the sim in sequences not normally met on operational flights. Sort of the trainers giving themselves negative training.

“During take off, with one hand on the controls and the other on the throttle, any such movement would be immediately attract attention, especially as the Pilot Monitoring should be scanning the instruments and not concentrating on any single spot.”

Usually, the PF would have both hands on the yoke during take off (or one hand on the stick and one hand in his lap in an Airbus) and not hold the thrust levers. They are in T/O power or climb power anyway and aren’t being manipulated, so there’s no reason to hold them.

I think that makes the point even stronger that the PM is in the easier position to reach the fuel switches, as the PFs hands aren’t anywhere near them…

Dammit. I had it right initially and then at the last minute, I saw a reference to one hand on the throttle. As I’ve never flown a Boeing (!) I presumed I had it wrong and quickly corrected before publishing. I wish I’d taken a moment to think it through; as you say, there’s no reason why anyone would adjust the throttle after V1. Thanks.

When you fly with an autothrottle you don’t place your hand on the throttle levers One directs the settings to either hold a specified airspeed, or a specified altitude and let the throttles dance by themselves to give you what you want?

With Autothrottle engaged you never have to touch thrust levers.Bit different from flying the DC-4.

It is quite uncanny hand flying a Boeing with the throttle levers literally dancing back and forth. It seems like a ghost is operating the throttles but that ghost is electronic. which is why I suspect fuel was cut off by the FADEC units, not the pilots.

The Preliminary Report does notsay pilots switched off the fuel. It only refers to fuel being switched from cut-off to run. The opposite to switching off fuel. The report says fuel was switched on.

The Prelim’ report notes RAT deployment and the APU autostart sequence had begun before impact. Some people may recall images of the til empennage poking out from a building?

A little inlet door was open and that was the APU air inlet.

it is hard to tell without FDR data, whether the RAT deployed due to electrical failure, or hydraulic failure, because the RAT supplies both electrical power and hydraulic pressure. but it is worth noting each FADEC uses the HMU (Hydro Mechanical Unit) to manage fuel supply to the engines, so if hydraulic pressure dropped the HMU might have cut fuel supply on AI171. I consider the Air India crash to be the result of Autothrottle rollback. not pilot action.

On the 737 FADEC are attached on the sides of engine H/P casings. HMU are located behind the accessory gearbox. Either this was caused by hydraulic failure or electrical issues(data interruption)

.

Simon, the preliminary report is very clear on the fuel switches:

The engines were working fine, then the switches in the cockpit were switched, and as expected, the engines started to slow down. This would also disconnect the electrical generators and deploy the RAT pretty much immediately. It explains everything, leaving no room (and no evidence) to speculate about hypothetical failures.

The captain would usually have a hand on the throttles during the take-off roll up to V1 to facilitate a quick rejected take-off, should that be necessary.

Some pilots also like to keep a hand on the autothrottle e.g. during descent, because it keeps them aware of what autothrottle is doing.

Interesting BBC article on this today: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cn9yw0rljwvo

Engines were not “working fine”

Liftoff was at: 08.08:39 UTC

RAT deployed 08:08:42 UTC(which is also when engines spooled down)

Fuel switches were moved to CUT-OFF at 08. 08:42 UTC (not prior)

In the 787 QRH listed at 7.2 (Ram -air turbine)

under

“Dual engine fail”

Pilots are instructed in any Condition: where engine speed drops below idle, Action: Fuel Control switches (both)

switch CUT -OFF, then RUN

Pilots must switch fuel to cut off and then to Run to recycle FADEC units to initiate engine relight. Unless we know why engines spooled down we are in no position to blame pilots.

In order to restart engines Fuel switches had to be switched off and then switched to run. Pilots only followed QRH instructions.

Yes, Simon, the memory item is “switch CUT -OFF, then RUN”, and not “switch CUT -OFF, wait 10 seconds, then RUN”, which is what actually happened.

You can’t just make stuff and expect everyone to believe it.

In a previous reaction I admitted to have been ignorant regarding these engine cut-off switches.

In my days, the power was cut off normally by the power levers, and under abnormal circumstances by the fire switches; in some older aircraft large handles that had a red warning light inside that would start flashing if an engine fire was detected. Activation was done by pulling them out, and the fire retardant was activated by rotating the handle. In other types, it would be a push button protected against accidental activation by a guard covering the switch.

Power could be restored by activation of the ignition and moving the power levers out of the detent.

Activation of the firewall cut-off usually could not be reversed by the crew, that had to be done by the mechanics after hopefully safe landing.

No doubt, there is a good reason.to install the switches in the B787, and place them low, at the back of the pedestal.

In the event of a flame-out, instant relight needs an immediate reaction. In some types of aircraft it is an emergency procedure starting with “memory items”. Worse: if fuel is re-introduced the procedure usually requires a gradual process. If the power levers are not first moved all the way to flight idle, a relight might either cause an overtemperature and turbine damage, or just fail to restart.

In neither case the engine will regain power instantly. Some engines require a minimum airspeed for a relight, unless the igniters are on.

A gradual restoration of power of course will not allow the aircraft to regain sufficient airspeed to resume its climb. It will have lost airspeed; close to the stall causing extra aerodynamic drag and even with the engines (still) in the process of spooling up the flight was doomed.

At least, in the older aircraft like the BAC 1-11 and biz jets that I have flown, cutting off the fuel would have been in full view of both pilots.

The fire cut-off handles or -switches are usually placed somewhere in the middle of the instrument panel, above the engine instruments.

Activation of them, as well as moving the power levers, is not easily missed by either crew member

In contrast, insofar as I can see, the B787 cut-off switches are out of the pilots’ field of vision. Moving them can quite easily be missed by the other pilot, especially if (s)he is concentrating on controlling the aircraft immediately after getting airborne.

Inadvertent cut-off instead of raising the gear?

Doubtful in the extreme. In all aircraft that I have flown, the gear handle is located at the bottom right of the panel, just above and right of the pedestal. Is this different in the 787? I doubt it.

I once witnessed a near accident of a Cessna 172, flown by two airline pilots with two other pilots in the passenger seat.

Apparently, the PF tested the engine using different tanks during the pre-task-off checks. He turned the fuel off just as he took off.

The result was fortunately comical: the aircraft could be seen climbing, then losing altitude, then climbing again. This happe3ned a few times in quick succession.

The fuel selector was mounted on the floor between the pilots’ seats and also accessible from the rear seats.

So four frantic pilots were frantically, alternatively turning the fuel “on” and “off” again. A typical case of too many cooks, but nothing happened in this case. They realised that the PF had correctly turned the tap back on, they stopped interfering and the aircraft flew away safely.

What exactly happened with Air India 171? Deliberate or accidental, and by whom? We probably will never know.

May they all rest in peace.

The Boeing 787 has the fire handled right below and aft of the fuel cutoff switches. These are right behind the throttles, so should be fairly visible, unless obscured by the pilot’s own arm.

The FADEC controls the engine; much like the magneto on a simple piston engine, it’s powered directly off the turbine and has power as long as the engine is rotating. The thrust levers are also wired directly to the FADEC.

The B787’s FADEC will automatically relight the engine if it can. This does require a certain minimum speed, but in the situation at Ahmedabad there is also a maximum speed: when the air is compressed at low altitude, it isolates so well that the igniters won’t spark. The compressor actually has to slow down to sub-idle for the engine to be able to be relit. And when that succeeds, there’s still a long wait for the engine to spin up again and produce power—much longer than AI171 was airborne, as it turned out.

The good news is, because the FADEC controls the fuel injection, it can do this at any power setting. Just keep the levers where they are, and wait for thrust to come back.

Rudy both engines commenced a FADEC relight sequence on 171 . Pilots did not switch off fuel the FADEC probably did that, but we hope to learn more later. Boeing does not want us to question the safety of FADEC, but a British Airways 787 suffered Autothrottle rollback in June 2025, followed by another a few days later. British Airways is quietly shedding its entire 787 fleet because they no longer trust the 787.

That directly contradicts the wording in the preliminary report:

Page 14: “…at about 08:08:42

UTC and immediately thereafter, the Engine 1 and Engine 2 fuel cutoff switches transitioned

from RUN to CUTOFF position one after another with a time gap of 01 sec.”

Page 15: “As per the EAFR, the Engine 1 fuel cutoff switch transitioned from CUTOFF to RUN at about 08:08:52 UTC.” … “Thereafter at 08:08:56 UTC the Engine 2 fuel cutoff switch also

transitions from CUTOFF to RUN.”

If the flight recorder didn’t see signals that the physical switches had been moved, rather than that the FADEC decided to do something odd, then that report is terribly misleadingly worded. There are oddities to what’s contained in the report (e.g., as Sylvia points out, the lack of identification of who’s speaking and clarity on what happened with the gear) but I seriously doubt they’d include anything which is effectively a lie.

Also, an uncommanded throttle rollback, which has been seen before on other Boeing types (747-400 IIRC) is, while far from ideal, quite a different thing from actual shutdown of the engines.

I agree with you, Ed. The flight recorder logs the position of the individual fuel switches via two of the four sets of contacts on the switch (parameter 35g). Another set of contacts drives a relay that signals the fuel pumps to shut off, that’s simple electronics.

The thrust lever position is also logged:

The autothrottle would have moved these levers if it had commanded the engines to idle. And unlike an engine restart, FAA certification demands that the engines go from flight idle to 95% thrust in 5 seconds, so if that ever happened, all the pilots need to do is push the throttles forward.

I could not find support for Simon’s claims:

1) British Airways is not selling its Dreamliners, it is getting 32 new 787s as of May 2025;

2) I could find no news of an uncommanded throttle rollback;

3) the autothrottle is not part of the FADEC anyway.

Simon’s narratives fail to align with reality.

Mendel,

A nice summary, thank you.

You are giving a bit more detailed information than I could. My comments, as I mentioned quite clearly, are based on knowledge and experience gained when actively flying. It relates to aircraft that may still be seen in a museum, or kept as static displays.

But whether controlled by FADEC or by less sophisticated injector systems as in older generations of aircraft, I am convinced that for a relight the power must be all the idle position. I am not sure that I understand your remark about […] “when air is compressed at low altitude, it isolates so well that the igniters won’t spark.”

I maintain that, in order to achieve an immediate in-flight relight the aircraft must have a certain minimum airspeed, otherwise it will probably lead to a compressor stall and an overtemperature.

So it makes sense to me that the FADEC brought the power all the way back to idle. At a lower airspeed, he relight sequence would have been more akin to an engine start on the ramp. This would have been in accordance with the abnormal procedures as laid down in the checklist.

The aircraft was at a dangerously low airspeed, probably close to the stall with the stick shaker rattling. In this position, (assuming that with the RAT employed, the shaker would still operate) the aircraft would have generated a lot of aerodynamic drag. If you are familiar with aviation, and obviously you are, you know about the so-called “power / drag curve”. The aircraft was in urgent need of power, a lot of power, for it to have any chance of recovery.

But as Sylvia explains, these enormous engines have a lot of internal inertia and need time to spool up before they could deliver the power needed. Time that they simply no longer had. Even if the engines had been able to roar into life instantly, they would first have needed to regain airspeed; A B 787 has a take-off weight of about 230-250 ton. A bit less when taking off under hot conditions maybe, but still a lot of inertia to overcome drag before the aircraft could accelerate and recover. Lowering the nose would only have been an option at altitude.

I feel very sorry for all those who lost their lives and people on the ground who suffered injuries.

My sympathy goes to their relatives.

It’s always a pleasure reading your comments, Rudy!

I forgot to mention that the fuel switches on the B787 have a red LED in the cap of the switch, and that serves as warning light when engine fire is detected.

I think we largely agree about the power: the FADEC is going to sort out exactly how much fuel the engine needs to successfully relight. Since it’s all regulated by the electronics, the pilots don’t need to move the thrust lever back; the FADEC is “watching the turbine” and only injects as much fuel as it needs to relight and spin up. It does that as long as needed until the power level matches what the levers command. There’s a lot of sophisticated engineering that goes into this to make the engine meet the FAA performance criteria, and to do so very reliably.

The preliminary report states the weight was 213.4 metric tons, MTOW is 218.2 tons.

Some people apparently tried the same maneouver in a Gulfstream G650 simulator: cutting both engines after 3 seconds and turning them back on 10 seconds later resulted in the same outcome, but waiting 10 seconds to cut them allowed them to recover with 80 ft. to spare. It’s a matter of energy (altitude and speed) at this point that determines whether the aircraft will glide long enough for the engines to deliver thrust again.

Traffic accidents are never a happy occasion. With cars, there are so many of them, and they’re often similar, and we understand them. Aircraft accidents are rare, especially in commercial aviation, so it’s always a challenge to understand them.

If throttle levers were in the idle position the it is likely the autothrottle retarded levers to assist engine relight sequence. . Engines would not have started with throttlespushed forward.

In any case with an Auto throttle a pilot merely requests more power The FADEC decides whether to grant that request?

The idea with Autothrottle is you line up, arm TOGA, tell the Flight Director what you want open the throttles and leave them alone

Perhaps nobody noticed but ADS-B data feed for this flight on the FR24 website dropped out implying electrical failure on Lift off when the RAT deployed. This means FADEC units on the engines had no information either. Engines already flamed out 3 seconds after take off. Thirteen seconds after take off the Captain (Pilot Monitoring followed engine restart procedure by selecting fuel CUT-OFF then switching fuel to run. This was not pilot sabotage. This was the procedure to restart engines.

Except that you interpretation is entirely inconsistent with the question about why the switches had been turned off, and the answer that they hadn’t…

ADS-B on FR24 is received by hobbyists with private antennas, and they don’t always have the greatest coverage, especially low on the ground. For example, the eastern half of the runway was not covered at all, so FR24 did not receive data for the runway taxi and the start of the take-off roll. To say that the power failed when FR24 stopped receiving data is jumping to conclusions, and it’s also at odds with the position of the aircraft over the runway with the RAT deployed.

The FADEC units are directly connected to the throttles, and powered of alternators linked directly to the turbines. As long as the turbine is rotating, the FADECs are powered and will respond to throttle inputs.

According to the EADR, the fuel switches were moved to CUTOFF 3 and 4 seconds after the aircraft became airborne, and moved back to RUN 13 and 17 seconds after the aircraft became airborne. The engine restart procedure does not involve a 10 second wait time; the pilot simply cycles the switch down and up.

Your theories do not match the facts as reported by the AAIB.

Another article from the BBC: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c33pzypkkdzo

It doesn’t really add anything but does confirm that lots of people are putting lots of odd interpretations on that preliminary report, some contradicted by detailed apparently well-informed comments here.

Yes. The Safety Matters Foundation is pushing for the full contents of the flight recorders to be released, which is very unusual. Richard Godfrey, who has put forth some far-fetched ideas that MH370 could be found by tracking amateur radio disturbances, pushed the idea that water ingress somehow triggered the engine shutdown, bolstered by sources that seem to be chatbot hallucinations.

The preliminary report is very clear that both fuel switches were flipped. By implication, that means the flight data recorder did not record any other anomalies; if the FADEC shuts the engines down, that would be recorded separately. If there was severe water ingress, that would be very noticable in the data, because it would affect many systems. The fact that the USA’s NTSB and the UK’s AAIB are part of the investigation, and have access to these records, and that they have not contradicted that preliminary report, shows to me very clearly that there’s nothing substantially wrong with it.

The investigators in India left the door open for a course of events where the fuel switch detente could have been ineffective, and the switches flipped by an inadvertant motion that neither pilot was aware of. (This is different from an “action slip”.) And they made no suggestion as to which of the pilots flipped the switches.

The upshoot is, some people shout very loudly “don’t blame the pilots!”, while the rest of us are waiting for the investigators to complete their job in a thorough manner.