A Lesson On Keeping The Aircraft in Trim

On the 28th of May 2019, a customer arrived at a flight school at Archerfield Airport, Queensland for their first flight experience.

The aircraft that day was a Cessna 152, a two-person, single-engine aircraft popular for training as it has low operating and maintenance costs but, more importantly, it is a durable and forgiving aircraft which is relatively simple to operate (slow, fixed pitch and fixed-tricycle gear).

The instructor pilot had about 320 total flight hours, with 100 hours in the Cessna 152, and had done this exercise seven times before. The student pilot obviously had not.

After the student pilot and the instructor departed Archerfield, the instructor went through a sequence of manoeuvres to show the student the effects of control. This exercise is meant to get the student familiar with the complex system of an aircraft and how a large range of different issues can affect the performance.

As a part of this, the instructor trimmed the aircraft nose-up while the student was flying straight and level and had the student maintain attitude using nose-down pressure on the control wheel yoke while retrimming the aircraft for level flight. The Cessna 152 has a manual trim wheel on the lower instrument panel which controls a full-span trim tab on the right elevator.

This is a basic exercise which is familiar to every pilot. If the aircraft is “in trim” then it will fly straight and level in the current configuration. If it is “out of trim” then it will be pitched nose-up or nose-down and physical force on the controls is necessary to maintain level flight.

So there’s a great advantage to keeping the aircraft in trim, although this needs adjusting frequently as minor changes to power or altitude will require adjustments to the trim. A bad pilot will not make these adjustments, instead modifying the pressure on the controls to keep the aircraft pitched correctly. If the pilot continues to fly out of trim, he or she will notice that the flight controls feel heavy and that the aircraft has a tendency to gain or lose altitude, depending on whether the aircraft trimmed attitude is nose-up or nose-down from the desired attitude.

The student flew straight and level at a height of 2,000 feet above ground level. When they were overhead Lagoon Island, the instructor turned the trim wheel by two thirds of its total travel to adjust the trim to nose down. The student was able to maintain straight and level flight by pulling back on the controls to counteract the nose-down attitude.

The instructor’s feet were on the rudder pedals and the instructor’s right hand was resting on the glare shield; both hands were near (but not on) the controls. The student continued to fly straight and level for a short time before being told to return the elevator trim to neutral. Normally, a pilot reaches the right hand for the trim wheel while maintaining pressure on the control wheel yoke with the left hand, thus keeping the aircraft straight and level. Then the instructor puts the aircraft out of trim in the opposite direction and the student flies straight and level before being told to put it back into trim again.

However, on the first instruction, the student completely let go of the controls which meant that the aircraft suddenly pitched down and rolled left.

The instructor’s headset flew off as they entered a dive of over 3,000 feet per minute. The instructor took control of the aircraft, pulled back the throttle and managed to arrest the descent at about 400 feet above ground level.

After recovering, the instructor carried out a flight control function check and confirmed that the aircraft was controllable. The throttle was bent from when the instructor had pulled it back but was still able to be moved. The instructor contacted ATC to say that the aircraft had descended one thousand five hundred feet quite suddenly and that they were returning to Archerfield Airport. They landed safely about five minutes later.

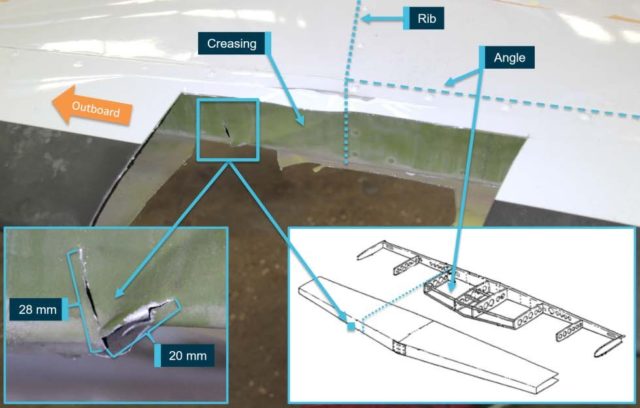

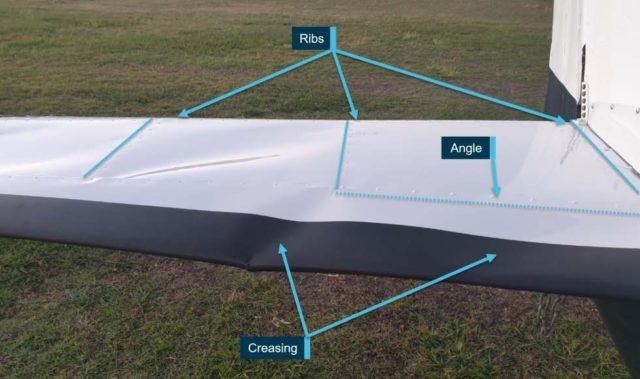

Once on the ground, they found that the Cessna 152’s right horizontal stabiliser was bent and twisted out of place by about 30mm (just over an inch), with rivets pulling through the skin. The internal structure was cracked and creased. There was no evidence of any pre-existing damage.

The instructor remembered applying right rudder during the recovery but couldn’t quite recollect why, or whether they were in a left spiral dive or spin. There was no time to re-trim the aircraft to neutral until they had pulled out of the dive.

The flying school’s instructor guide did not put a limit as to how much nose-down or nose-up trim to apply when putting the aircraft out of the trim for the student to recover. Because the instructor had set it two-thirds nose-down, the aircraft pitched abruptly down when the student let go of the controls. The instructor was not guarding the controls and clearly was not ready to quickly take control of the 152 when the student let go. Instead, the instructor’s right hand was resting on the glareshield which led to a delay before taking control.

The instructor then attempted to regain control without placing the trim back into a neutral position, which made it much more difficult to recover from the dive. Because the trim tab was on the right elevator, aerodynamic forces were concentrated onto the right horizontal stabiliser rather than being split between the two. The elevator trim added additional load to the right side which twisted the stabiliser down.

Investigators found that the right stabiliser was close to total failure.

Contributing Factors

In the course of the student pilot’s first training flight, during a lesson in the effects of control, the student released control wheel backpressure suddenly.

The instructor’s use of a large amount of nose-down elevator trim for the lesson increased the effect when the student released backpressure on the elevator, leading to a sudden nose-down pitch change and subsequent entry into a dive. The instructor was not prepared for the sudden nose-down pitch change, leading to a delay in the recovery from the dive.

Other factors that increased risk

During the recovery from the dive, the horizontal stabiliser experienced excessive asymmetric flight loads, resulting in bending and buckling of the right horizontal stabiliser structure.

The training school revised the instructor guide with a new procedure for teaching students the importance of trim. The instructor is now expected to place the aircraft into a cruise climb and show how the use of trim can reduce control loads on the flight controls, in order to show the student the effect that trimming has on the aircraft flight characteristics and maintaining flight attitudes. Then the instructor demonstrates the manoeuvre before allowing the student to practice it, putting the aircraft into a nose-up configuration and with a specific (moderate!) amount of trim input in order to show how to maintain the best rate of climb.

The photographs tell the story although I have to admit I’m amazed at how much damage was done over in the course of a dive recovery.

The instructor was clearly not alert and ready and I’m not sure revising the instructor’s guide feels me with confidence. I sure hope that both the instructor and the person who did the instructor’s training have gone in for remedial training.

You can pick up a copy of the full report on the ATSB site: Loss of control involving Cessna 152, VH-JIW, 34 km east-south-east of Archerfield Airport, Queensland, on 28 May 2019

I’m not sure the concept of trim applies to a helicopter – which I’m trying to learn to fly, with instructed help. Most of the time it seems our flightpath looks like we were playacting as dolphins.

“A bad pilot will not make these adjustments,…”

True, but this was an exercise, demonstrating the effect of the controls and the trim. The student was obviously not yet ready for all of it.

In the start of this article, I read that this was “…their first flight experience.” Sylvia probably means his or her first flight experience, normally it is a two-seater. Although the Cessna 150, the predecessor of the152, in which I did my first dual cross-country flight had a third seat in the rear luggage compartment. It was a C.150D, registration 5N-AFR, in Nigeria on 24 June 1967. It was at the end of the hot, dry season. We carried three adults: My instructor, myself and a woman who was another student. We flew into a very short strip, Oyi Rivers, where we had to make the approach between trees. I even did a solo circuit there. We also did spins with the 150 (not an Aerobat). They did not suffer structural damage from all this.

This all to demonstrate that the Cessna 150 was in fact a very rugged and capable aircraft.

To suffer the sort of structural damage that the aircraft that features here it must have been subjected to a very high load, without doubt far in excess of the design limits.

A total flying time of 320 hours is respectable enough, but this story suggests that it was not really suficient for this young pilot to instruct or, at least, know his (her) limitations.

Was it normal to bring the aircraft so far out of trim, and alternating between trim “up” and “down” with a student on his or her first flight? Was it wise to go this far? And, assuming that it was indeed in the syllabus, should the instructor not have been ready to take over the controls at once?

In my experience, during a first flight lesson, the instructor will demonstrate all the controls and gently, gently, allow the student to get the feel of the aircraft. For an experienced pilot this is the proverbial “piece of cake”, but many people on their first introduction will become quite easily overloaded. An aircraft moves in a three-dimensional environment and this alone is a new experience. A good reason for the instructor to do a good bit of the flying him- or herself and when handing over to the newbie student have the hands very close to the controls or, if deemed OK to give the student some confidence, be ready to take over at once. And that means: keeping a very close eye on everything, frequently watching the student.

How far an instructor can allow a student to go depends of course very much on his or her own experience.

I cannot help feeling that this instructor exceeded, and overestimated, his (her) own abilities when doing this exercise.

At least there were no casualties – other than the aircraft.

The instructor did pull it out and fly home, if not optimally. Hard to be too hard on them for this.

More usefully, what I’m impressed about is not so much what the aerodynamics did to what looked like a stiff structure, but how that structure deformed and yet continued to work even if a little bent. J.

Jon,

I have never been qualified on helicopters, but from my very little experience I seem to remember that it requires very light control forces on the stick and it did not seem to have much feedback in the controls.

A very light touch was enough, the pilot who allowed me to handle it only realised that I had no experience at all was after I had already landed (safely).

Apparently, a helicopter is kept a bit high so that in the event of an engine failure there is enough heigth for an auto rotation.

I made my approach like a good fixed-wing pilot: with a 3 degree approach path.

I was hard on the instructor, yes.

An instructor is responsible fot his or her students.

The instructor is, in the air, the all-knowing “God”. Yes, students in their early career reallylook up to their instructor.

For good reason, (s)he is the one with the experience who can teach them the tricks to control an aircraft, in three dimensions.

Many years ago I was a member of the Tiger Club, then still at Redhill.

On the instrument panel of their aircraft were little placards, proclaiming:

ALL AIRCRAFT BITE FOOLS

I’ve done the trim teaching exercise 100 times as part of intro flights for the PPL. I teach it naturally as trim changes become required during the phases of flight. There’s no reason to show a student a complete out of trim condition on their first flight, I show it latest when they have to start being able to do go arounds which is several flights later.

Visiting a young man who had worked for me years before, it came out that he had just been granted a PPL. He was all excited but wanted aerobatic training.

The FBO he got his PPL from had a 152 Aerobat so we rented it and up we went to see if it was something he really enjoyed.

No parachutes and the ink still wet on his PPL, I took it easy, doing positive G maneuvers with him in the left seat, hands on the yoke and throttle.

The fellow was really comfortable so after a 1G loop and lots of rolls, I said, “take her up to 5000′, pull her into a hammerhead stall, chop the throttle and pull the yoke into you guts. Hold it there till I tell you to neutralize it.”

She snapped nice and sharp, fell off the left wing and we went into the slowest, most nose down spin one can pull in a Cessna. Then things got all lossy goosey,

I pushed the yoke forward, No resistance. Broke the stall with the rudder and the bird settled into a more or less level flight.

The friend ask, what happened? Don’t know but we need to find out.

No down elevator. Everything else worked just fine but you could push the yoke out past the prop and down was not to be had.

The young pilot was taking this really well, he ask, “so what do we do” answer, “fly the airplane”.

Landing a 152 without down elevator authority is really no big deal and deserves no credit. The young pilot, not losing his cool does.

On the ground, we found that the lower half of the elevator bell crank had fractured. I’m guessing from some hotshot wannabe pushing the plane past its limits. It looked Ok during the Preflight. These things happen when you rent aerobatic aircraft.

The young pilot went on to buy a Decathlon and become a damn good pilot. He and I had some fun in a Carbon Cub a few years ago.

“Fly the Airplane” was hammered into my head from my first flight.

Once when I was teaching a young woman to drive a car, with an automatic transmission, I asked her to take her foot off of the brake and step on the gas pedal. We started moving forward, then I asked her a question about the road we were driving on, she looked at me and too both hands off of the wheel so she could gesture while she spoke, the truck was moving the whole while. Fortunately I had chosen a back road that at that time had no traffic, and we missed a mailbox (although I’m not sure by how much). I don’t understand how people think sometimes, but as you say, as an instructor you have to be prepared for anything, this on was clearly not.

Just trying to be helpful:… where you have written “Once on the ground, they found that the Cessna 172…etc” you had said it was a Cessna 152? I greatly enjoy your articles and photos. Stay safe and healthy!

Oh ack! Thank you for that, it was a 152 and I clearly lost the plot. Fixed now; that;’s definitely helpful

“with a specific (moderate!) amount of trim input” — Rudy pointed to this, but it was also my first reaction; giving someone on their first lesson that much to handle reflects badly on the instructor, as does his not having hands right by the controls when he told a beginner to fix a problem he’d set — if it’s a student you haven’t already worked with, how do you know how (well) they’ll react? (cf Mike S’s tale of a student driver.) Shortly before I learned to fly, I learned the basics of engineering a radio broadcast, and discovered how much harder a task you’ve just learned becomes the instant you’re handed another task alongside it, and how easy it is to lose track of the first while handling the second — even when you’re standing on solid ground! I also remember how exciting my first flight was, WITHOUT the instructor throwing something hard at me.

This article provoked an interesting discussion about air(wo)manship.

Igeaux’ comment is also interesting.

Back in the ‘seventies when I was flying a Cessna 310. My employer had frequent business in the London area, often with overnight stops, so we were regular visitors at London Gatwick.

Needless to say that I used the opportunity to visit Redhill, then the home base of the Tiger Club, to fly a Tiger Moth, or any of the other aircraft available in the fleet.

The standard aerobatic trainer was the Stampe SV 4. They were equipped with g-meters. They had three needles: One indicated the actual g at the moment, the other two remained at the maximum positive and negative g that the aircraft had been exposed to during the sortie. They could be reset with a push button. Neil Williams, who was the main aerobatics instructor, always made certain that we would NOT reset the g-meter. This was for the next pilot, so he or she could see what the previous pilots had been up to. If the limits had been exceeded, it had to be reported to the mechanics.

Neil had once done some training in a Zlin. It has been suspected that a previous pilot had overstressed the aircraft, reset the meter during the flight and did some less stressful manoeuvres to hide it.

A wing broke, folded and Neil did not wear a parachute. Somehow he managed to bring the aircraft down in a controlled manner and walked away from the wreck. It still ranks as one of the most skillful accomplishments of any pilot. No wonder that he always made sure never to fake the forces that the aircraft he flew had been subjected to.

I was not one of his star pupils. He was keen on competition flying and was teaching the “Aresti” system. Aresti was an aerobatic ace who had devised a system of symbols to indicate a particular figure or manoeuvre. They would be drawn on piece of paper, representing a sequence and put on a kneeboard. The problem was that the sequence was to remain within a certain part of the sky, in view of the judges.

“Flying Aresti” was definitely not a sequence of gentle rolls, loops, spins. It was very abrupt and it would require a pilot to do very frequent and regular practice to get used to it. I was not going to do competitions, just wanted to learn some basics and besides, I was not often enough at Redhill to go for intensive training. Nor could I afford it. So I never built up the physical resistance against the rather brutish force of the Aresti-style.

But Neil was always very much aware of how far he could go with a student. He reduced the stress, sometimes just allowing me to relax by doing some inverted flying. The Stampe had a fuel system that would allow this, albeit for short periods at a time. So he would teach me how to fly a circuit inverted, then would take over on finals to roll it upright for me to do a landing or a touch-and-go. A bit intimidating at first in an open biplane, and it drove home the importance of being tightly strapped in.

On one of my first trips off the circuit after first solo I decided to practice steep turns at 1,500 feet. Yes, it should have been 3,000. I must have got too much top rudder on in a hard left turn because the Champion 7EC flicked over the top and spun to the right. The flick was just a blur. Hanging in the lap strap – no shoulder harness in 1961 – I remembered a poster on the clubhouse wall, about spin recovery. ‘Throttle closed, full opposite rudder, ease stick forward, centralise rudder and recover from ensuing dive.’ Did all that and didn’t lose more than about 700 feet.

Moral? Either ‘Follow the rules’ or ‘Read the posters on the wall’. Take your pick.