More from the Lagos Flying Club, 1968

I’m pleased to share another post from Rudy and his early flying days during the Nigerian Civil War. All of the photographs were taken by Rudy at the time. It’s fascinating stuff; I hope you enjoy it as much as I have!

-Sylvia

More from the Lagos Flying Club, 1968

by Rudy Jakma

When I was only a few months in Nigeria, the south-eastern part declared independence, calling itself “Biafra”. The majority of the people there belonged to the Igbo tribe. There was an initial shock, nobody knew how strong Ojukwu’s army was. Soviet Russia threw its weight behind Biafra, they had some initial success on the ground, but apart from some Egyptian Migs, Biafra did not really have an air force.

Just as well, because neither did the federal Nigerian government.

The Nigerian government nearly overnight replaced all its currency: the colour of the banknotes changed from red to green. Anyone wishing to exchange notes had to prove that the money was earned and held legally. There was a very short grace period. Large amounts of cash had been spirited out of the country and held in foreign safe deposits. Millions and millions were under threat of becoming worthless overnight. Suddenly old airliners, Constellations, DC 4s were underway to repatriate money before the deadline. In, I believe Niger, an unregistered DC-7 full of (old) Nigerian banknotes was stuck with a technical problem and impounded. My employers, Pan African Airlines, were very busy too, bringing the new money all over the country to be redistributed and returning the old ones to the Central Bank. Pan African even chartered a Convair 580 from the Dutch charter airline Martinair.

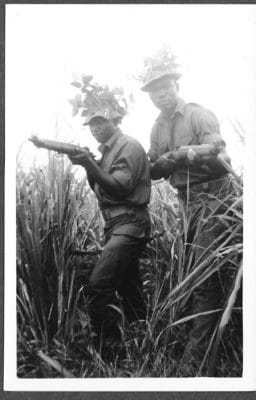

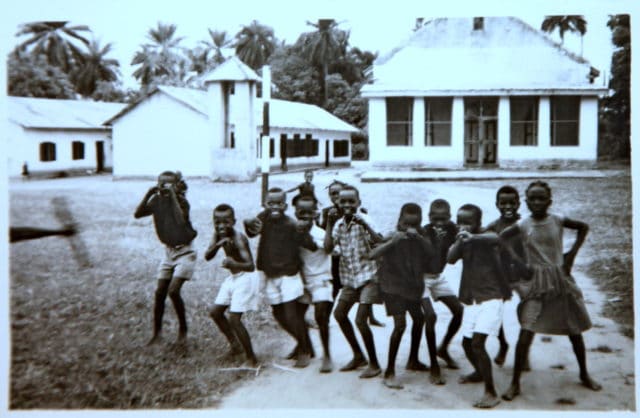

The activities of Lagos Flying Club soon returned to normal, as long as we avoided the areas where the war was still in progress. KiriKiri was again a hive of activity, we even flew to other places: Ibadan, Cotonou, and Benin with a Dutch friend and two Nigerians. We stayed overnight in the house of a friend and went into the jungle.

Eventually it became clear that the war was not going well for Biafra. Pan African chartered a few DC-4s for relief goods. At night they flew arms and ammo for the army, during the day Red Cross relief goods.

One of the first captains who came with the DC-4s was Elmer Kiss. He did more flying than we would consider safe today and the resulting antics at first flight of the day were sometimes hilarious. The DC-4 did not like to start when the engines were hot. The engineers always did a run-up before the first flight. The result was a frustrated pilot, hanging out of the cockpit window, cigar dangling from his mouth.

Normally the no 2 would be started first, followed by no. 3. The inboard engines had the alternators and hydraulic pumps for the brakes, so when it came to no. 1, the other 2 should have been running. But if they wren’t, there would be a call for extra chocks accompanied by a number of well-chosen expletives. “You gold darned mother chuckers, I told you not to start the gold darned engines.”

“Yes captain, but the chief pilot ….”

“I don’t give a gold darn for what the gold darned mother chucking chief pilot said.”

You get the drift.

Kiss did the flight with arms in the evening, and after that went home for a “kip”. In the meantime, a man with a broom and a bucket of red paint would paint red crosses on the tail. Kiss, after a few hours sleep, would return with his copilot and do the Red Cross flights. After which the guy with the broom would return with a bucket of white paint and paint over the red crosses.

The inevitable happened: Kiss returned quite agitated. “Tell the gold darned mother chucking loaders to pay attention to the gold darned loadsheet. The gold darned mother chucking aircraft is tail heavy!”

After some of those heated exchanges, someone realised that the problem was caused by the red-over-white-over-red-over-white… paint.

After this, every second day the paint was scraped off.

Kiss lasted one month, but he left with hard-earned greenbacks in his back pocket, US dollars that he collected as “danger money”, probably $30,000 or even more. And it truly was dangerous work, because he was flying into and out of an active war zone, using landing strips at night that were only illuminated by flares just before starting to make the approach..

After that, three more DC-4s arrived. One disappeared. It had arrived in Africa, but was more than a week overdue. Communications were not great: no news = bad news.One morning, I heard the sound of an arriving DC-4. None of ours was due in, I knew them by sound. So I told Capt. Tracy, the chief pilot, that I’d better go to the apron and see if I had to do the customs formalities.

Tracy told me not to bother. “It is lying somewhere in the jungle or at the bottom of the sea” was his opinion.

But I went and yes: there was the missing aircraft.

What had happened? Somewhere they had had mechanical problems. The telephones were not functioning but they did carry spares and mechanics. The crew had run out of money and camped in the aircraft whilst the mechanics used the spares to fix it.

I had passed the test for my PPL the year before, in September 1967. We had to go to Cotonou in Dahomey, the country which now calls itself Benin. But the situation stabilized soon enough. Biafra did not have the funds to keep resisting the Federal troops. The West had too much interest in the oil and the Soviets did no more than stir up trouble. A few Russian-built jet bombers appeared at Lagos, after a navigational error, and were impounded. (In 1982 they were still there, nearly covered in the encroaching bush.)

Pan African brought in a few DC-4s for relief flights and to transport weapons. During the night they landed on dark strips with some basic lights turned on just before they arrived. Sadly, one, bringing 52 solidiers to the front, crashed when the crew misjudged it. All on board were killed.

The restrictions on private flying were lifted soon enough, the only restrictions were the south-east of Nigeria, the area that had tried to separate but failed. It did not take long before we were practising night touch-and-goes. In September 1968 it became clear that it would be over soon. Outside their own territory Biafra soon ceased to be a threat. I went along on a few relief flights and got some actual time handling the DC-4.

That was when a few journalists were looking for an aircraft to bring them to Port Harcourt, which had recently been re-captured by the federal Nigerian army. They had a letter from the military commander there, inviting them and authorising them to fly in. We did not have anything, so I told them to check with Aero Contactors and other commercial operators, but they had been there already. After the journalists had exhausted their efforts to charter a proper commercial aircraft, we hit on an idea. I agreed to fly them in a Cherokee 180 on a shared-cost arrangement. Lagos Flying Club had one, registration 5N-ADC, which we were able to use.

The journalists had a permit from the colonel, the commanding officer at Port Harcourt (DNPO). The ATC controller was reluctant to allow me to depart, but relented when he saw the permit.

Since it was uncertain whether or not we could get Avgas at Port Harcourt, I made a fuel stop at Escravos, and off we went again.

We had been told that we were supposed to contact Port Harcourt on frequency 121.5, the emergency frequency, but I could not get any reply.

It seemed unlikely that we were going to encounter any other traffic. The Cherokee had some instruments and I, with a proud total of nearly 125 flying hours, decided to climb into the overcast and make a “stealth” approach. I did the repeat trick of my solo cross-country, only this time IMC. I kept my heading and kept calling Port Harcourt. To no avail. When I calculated that we should be there, I made a 360 and… came out of the clouds on finals. So I landed, as would be usual in Germany: at my own discretion.

We were instantly surrounded by soldiers. Not unfriendly, but they wanted to see our documents.

As it turned out, the colonel was still in Lagos and had not told his people in Port Harcourt about our arrival. Fortunately, it was soon sorted out when the permit was produced. But a sergeant told me that we were lucky. The Cherokee was blue and white. They were expecting a blue and white aircraft and we came out of the clouds and had landed before they realised that we were not the one that had been expected. It landed half an hour later, a DH Beaver of Aero Contractors.

The sergeant told me that if I had made a normal approach, under the clouds, rather than obscured by them until the last minute, his men probably would have opened fire.

An officer, a captain or a major arrived and left with the journalists. I was uncertain what to do, but another officer, a lieutenant, came to tell me that the journalists were on their way to the war front. I was told to leave and return two days later to pick them up again. But then, I was ordered to wait and bring two people to Escravos and Warri.

I had been chatting with the soldiers who were quite friendly. I asked them if they would be able to recognise the Cherokee when I would return in two days’ time.

The reaction was disappointing: a shrug and a hmmm…

I had a brain wave. A good one this time.

“How are your supplies here? Do you have any beer?”

No, they wished…

“OK, look at the aircraft here. In two days I will be back, no passengers. I will bring beer for you, as much as I can carry. So if you shoot me down, you will shoot your own beer down.”

Now THAT they could understand.

The two passengers arrived. I had no choice: I was in a military area, in an active war zone. It was an order and I had to obey. After I dropped the second passenger off at Warri, now empty, I was about to depart when a young pilot flying a Piper Aztec approached me.

He was on a regular commercial run back to Lagos. One of their aircraft, a Navajo, had made an emergency landing near the Niger Delta.

The aircraft had to be written off but the avionics had been salvaged. Because of the damp and salty environment, they had to be brought to the avionics repair shop at once. Could I take one of his passengers? Of course not, they were commercial passengers.

The journalists were sharing the cost, the army had ordered me to bring the other two from Port Harcourt, but fare paying passengers? That was clearly out of the grey area. I had to refuse. But: why don’t you put those avionics in my airplane, I will deliver it as a friendly gesture.

At first, the pilot did not want to do this. Nearly new equipment, worth a lot of money.

“Well, then it will stay here.”

He saw my point. I brought the avionics to Lagos and delivered them to Aero Contractors’ workshop.

Two days later I went back to pick up the journalists. My logbook says that I landed again at Escravos, probably for fuel, but also at Warri. Of course I had bought a few crates of beer.

When I approached Port Harcourt and contacted them the VHF was operational. The first question was: “Have you got the stuff?”

“Affirmative.”

“Clear to land.”

At the parking, within seconds, a jeep arrived to collect the beer.

I left Pan African a few months later, my contract was finished. The country had changed, it had lost some of its innocence. It had been a good time, but now it was time for a change. In the Netherlands I enrolled for a CPL (Commercial Pilot Licence) course.

For a long time, Aero Contractors chased me for a very hefty bill for landing fees at Warri. No credit for bringing their avionics back to Lagos.

The flying school that did courses for the theory for CPL and IF (Instrument Flying) were under the same ownership as Aero Contractors and eventually the landing fee issue was solved.

–Rudy

Sylvia makes a tremendous work with fearoflanding, but Rudy, I must admit that your contribution to the site make me check regularly for your comments. All old stories you share with us, is very interesting to read. Now you did remind me about the war in Biafra and the Swedish pilot Carl Gustaf von Rosen. It is obvious that both you and he were flying in Nigeria during the same period. Your were young while von Rosen was about sixty years old. His activity in Nigeria created a huge amont of articles in the news papers, at least in Sweden. It also created a headache for the government. From Wikipedia: On May 22, 1969, and over the next few days, von Rosen and his five aircraft launched attacks against Nigerian air fields at Port Harcourt, Enugu, Benin and other small airports.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Gustaf_von_Rosen

Oops! My knowlegde of African geography seems to be poor. I had no intention to mention Ethiopia. Of course it should be Nigeria! Maybe I was influenced from the information about von Rosen; he did work in Ethiopia as well.

Sylvia: Would you be so kind to correct my original text? Two times Ethiopia should be Nigeria.

Done but I’ve left this here so that Rudy’s reference to Ethiopia has a back reference. And interesting tie-in with von Rosen!

Leif,

I must admit that I totally forgot about Von Rosen. Yes, he did do a bit of damage but it was not a lot. The way I remember it, he flew a Bolkow Junior with a few bombs underneath. The performance would have suffered in the hot climate, he certainly did not have a lot of impact (pun intended) in Federal Nigeria. He did get some headlines but damage? No I don’t believe that he was very successful. It was more psychological but it did not even last a week. Biafra soon ran out of options: no suitable airstrips and more than likely a lack of fuel and other technical support.

Biafra did use a few DC3s that had been on the ground when they overran a few airports. Nigeria Airways still operated them. They flew at night and dropped bombs. Very funny, in a way: the bombs fell near the army headquarters, Dodan Barracks. The military did not have anti-aircraft guns so they used cannon that fired genades. These missed the aircraft and landed near the navy base at Apapa. The navy woke up and shot back. So the Nigerian army and navy opened fire at one another. The damage was very minimal.

Next, Ojukwu managed to capture a Fokker F27 of Nigeria Airways. They did bombing runs with that one as well. They just dropped the bombs from the rear sliding door. But that did not go well: Insofar as I could make out, the bombs were primed, to go off with a time delay and cast out of the door. One rolled back away from the door and before the crew could get it it went off inside the aircraft. I have seen the bits in a hanger at Lagos Airport. Of course, the army claimed that they shot it down but investigators told me that it had been a bomb inside.

And regarding Ethiopia: I had only just done my PPL in Nigeria. I have been in Addis Abbaba once, much later and only at the airport in a Cessna Citation. On a not quite legal flight but maybe…

The story of that trip is hilarious. Coming to think of it, I broke quite a few rules before I was tamed by the more sedate airline-style of flying.

Although… ah, no let’s not talk about that.

“Although… ah, no let’s not talk about that.”

Oh yes, let’s! :D

“Although… ah, no let’s not talk about that.”

You must write about that. Otherwise the most interesting bits of your life will be lost forever like tears in the rain.

You said Soviet Russia threw its weight behind Biafra? Are you entirely sure of this? If indeed true, why and how did the romance go sour? I ask because Biafra did not have the kind of support that was available to Nigeria otherwise, the war would not have been more drastic on their end and secondly, the ensuing genocide would either not have happened or its perpetrators would have received their fair share of justice by now.

Good catch! I’ve just taken a look and it looks like Rudy misremembered. The Soviet Union supported the existing government and supplied aircraft, whereas Biafra had the support of France and Israel.

“Once again, if they had to repaint an aircraft every time it loaded medical supplies, no airline would bother. The medical supplies would sit unused at the airport.” Words of a commenter on avherald, on the aircraft shot down by Ethiopian troops on May 4th. Little does he know!

An old one and I missed the last comments. Just in case someone re-reads them:

1. The Soviet Union supported BIAFRA. In a back-handed way. The real issue was oil. The Niger Delta had (has) ample supplies that were in the hands of American companies: Gulf Oil, Mobil Oil and drilling company Global Marine (Howard Hughes) as well as British interests (Shell-BP). France? I never heard of their involvement, nor of Israel, but the situation was murky. Von Rosen did a few unsuccessful sorties. The Soviets did send a few light bombers that lost their way and were impounded by the Federal government. They did not have pilots who could fly them, so they were parked along the side of the short, disused runway where they still were when I returned in 1982 to fly Learjet 25D, 5N-ASQ.

The Russians also provided Biafra with Migs. They did not want to be involved directly, so the aircraft were officially Egyptian and flown by Egyptian pilots. They were new to the Nigerian geography and missed Lagos altogether, they overshot it and landed at Cotonou, then the capital of Dahomey, later renamed Benin. They did not really feature in the war.

2. The DC-4 was not repainted every time, it was only literally a job with a bucket of paint and a large brush on a stick, like a broom. Eventually the weight of the paint started to accumulate on the tail. It may even have affected the airflow. This was not an airline operation, it was flying provisions and military supplies into an active war zone!

3. An aircraft shot down by Ethiopian troops? Never heard of it.

4. If Sylvia knows of the Soviets backing the Federal government of Nigeria, well that is news to me. See 1: It was all about oil. The oil fields were under control of western companies. A Biafran victory might have changed that in favour of the Soviets. It was still very much cold war. The Feds would not have thrown in their lot with the USSR as it would have endangered their relationship with the West.

5. I was there at the time when it happened !

The accident happened a month ago, in Somalia.

They shot at another airplane on May 25th, but that managed to land safely.