My Most Difficult Landing Taught Me Why Pilots Are Natural Leaders

I’m thrilled to bring you a special guest post this week by Steven Myers, a two-time US Air Force veteran with twelve jet-type ratings. In 2020, the FAA awarded him the Wright Brothers Master Pilot Award for 50 years of accident-free flying.

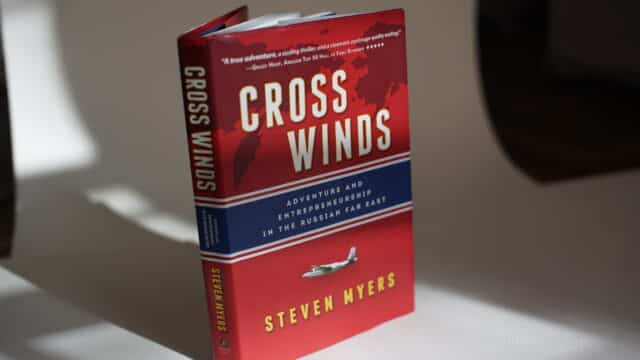

Myers has chronicled his adventures in his book Cross Winds: Adventure and Entrepreneurship in the Russian Far East, sharing how his experience as a pilot informed his work as a CEO and director of a number of public and private companies.

He’s here today to tell us about his experiences landing Russian’s easternmost Siberian military airfield and how it shaped his understanding of leadership.

My Most Difficult Landing Taught Me Why Pilots Are Natural Leaders

by Steve Myers

In July of 1992, shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union, I became the first American since Charles Lindberg, in 1931, to fly an aircraft into Far Eastern Russia and down the Kamchatka Peninsula. There I formed the second-ever Russian-American Joint venture, with the leaders of the region. My best-selling book, Cross Winds: Adventure and Entrepreneurship in the Russia Far East, describes this high-risk adventure to make an audacious multibillion dollar vision a reality. Success depended as much on my aviation skills as my entrepreneurial acumen.

No aviation challenge I’ve ever experienced compares to the challenges, difficulties and dangers of operating in this remote part of the world, in an age before any of the digital innovations or navigational support we all take for granted today existed. Imagine flying in a remote environment where the weather is sketchy at best, the controllers don’t speak English, the instrument environment is primitive at best, and what few charts you do have are un-decipherable; copies of copies of old charts designed in the 1950’s with procedures that no one has flown in the west …ever!

One landing in particular, in Anadyr—Russia’s easternmost Siberian military airfield, located at the northern tip of a peninsula adjacent to the Bering Sea—stands out as the most difficult I’ve ever made. As we taxied out of the Korf ramp area, at the north end of the Kamchatka Peninsula for the flight north to Anadyr at 4:00 p.m., the weather was already deteriorating rapidly, with broken clouds, strong winds, and light rain. Two hours later, when we reached Anadyr, the weather was considerably worse, with fierce winds coming out of the west. It was not until I lined up with the Anadyr’s only runway, running north to south for landing, that I understood how fierce the winds really were.

I recognized immediately that we were in trouble. Pushing on the right rudder pedal, I had to yaw the airplane thirty degrees to the right of the runway to keep the airplane aligned with the runway, something called “crabbing.” The rapid wind fluctuation made matters worse. I had to continuously adjust the crab to maintain runway alignment.

To appreciate this situation, imagine steering a boat into a dock in a strong crosscurrent. You steer the boat into the current to keep moving in a straight line toward the dock. The stronger the crosscurrent, the larger the crab angle. The more you slow the boat as you approach the dock, the larger the crab angle, and the more difficult it is to keep from being moved down current. Now imagine the current speed keeps changing. Everyone in the boat gets whipsawed by constant adjustments.

At a 90-knot approach speed, a thirty-degree angle into the wind meant that the crosswind component was 52 knots! There was no way to set the airplane down on the runway without sliding so severely to the left that I’d lose control of the airplane, break the landing gear, and probably much more. The maximum demonstrated crosswind in this aircraft (an Aero Commander 690B propjet) was 35 knots. There was just no way.

Viktor Shlyaev, my Russian military navigator, reported gusting and highly variable winds out of the west at 30 to 40 knots on the ground. I said, “Viktor, I’m going to continue the approach and see what the winds are doing near the ground. I don’t think we can land. You’d better start working on where we’re going with ninety minutes of fuel. We can easily make Provideniya with this tailwind.” Viktor just shook his head as he looked to his left through my front window at the runway. It was a sight neither of us was used to.

I stopped the descent at ten feet and flew down the 10,000-foot runway at 90 knots with the nose still pointing far to the right. I left the flaps in the approach position, assuming I’d have to abort. Along both sides of the runway, we zoomed past dozens of MiG fighters. I was too busy to notice. I waited and thought.

Viktor looked over at me from the copilot seat and said, “What are you doing?” I didn’t reply. I just waited and counted. 90 knots is 1.5 miles a minute. I had 45 seconds left to catch a break and still have enough runway to stop. Finally, at the last moment my chance came. The plane began moving to the right of the side of the runway as the wind momentarily subsided. I adjusted the rudder and ailerons to stop the airplane’s sideways movement. The airplane’s nose began moving left. I still had a third of the runway left. It wasn’t going to get any better. It was good enough. I chopped the throttles and aligned the airplane’s nose with the runway. In only a second, the main wheels firmly connected with the runway. With my left hand I simultaneously pushed the yoke forward to force the nose wheel onto the runway, while turning the yoke to the right to kill the lift on the right wing where the wind was coming from, began maximal breaking with my toes, while my feet danced on the rudder pedals, and my right hand moved the propellers into maximum reverse, beta mode. It looked like a circus act with every extremity doing something different and all at the same time. Viktor just stared at me. He said he had never seen anything like that before. I was shocked at how quickly we stopped. We sat on the runway for a moment, the wind severely shaking the airplane and beating fiercely against the control surfaces. I was barely able to keep the aileron, elevator, and rudder controls from moving about wildly. I looked over at Viktor and back at the others in the cabin. To say that we were all very relieved to be on the ground was an understatement.

Actually, I loved every minute of it! Perhaps it was my eternal sense of optimism, or perhaps my high tolerance for uncertainty. Either way, this risky but thrilling experience is a perfect example of how pilots need to think, act and solve problems. It also demonstrates four skills pilots have and use constantly that make them not only aviators, but natural leaders.

Keep your options open. Pilots know that, especially in the face of challenges, it’s crucial to not commit to a single course of action until you must. We have a Plan B for every situation. While approaching Anadyr, I told Viktor early in the process to start planning how we were going to get to our alternate airfield in case we aborted. This was a clear message that I thought we might have to abort. By the way, he didn’t want abort because he lived in Anadyr and hadn’t seen his wife in two weeks. I didn’t want to abort because I knew the alternative and “awful” is just too kind a word to describe it.

Similarly, leaders must be able to take the emotion out of decision making and stay open to alternative plans regardless of whether they like them. So many pilots have died because they needed to be somewhere. So many leaders, especially business leaders and entrepreneurs, have failed because they were over committed to a specific vision. The weather just doesn’t care how you feel or what you want. Critical decisions in any field have a way of being… inconvenient.

Know your abort criteria. This goes for takeoffs, landings, diversions, and for every business decision an entrepreneur makes. The Anadyr landing only happened because I was patient enough to wait for the right moment, which I had no way of knowing would or would not happen. Because I had done my homework, I knew exactly how much time I had to work with. I used it to plan for both the landing and the abort procedures. This wasn’t a movie. No heroics. Either I knew I could do it, or we were out of there. No guessing allowed!

Focus on the right things at the right time. No one cares about the guy who almost landed the plane or almost closed the deal. It’s not done until it is done and done right! In flying it’s so critical to recognize that you’re not done until the engines are stopped, the brakes set, and all the switches are off. Just as attention to every detail is key to a successful flight and landing, it is equally critical to leadership and business success. Leaders must be concerned with not just what needs to be done, but how, when, where, and in what firing order.

Communicate your intentions clearly. There is an old adage in flying: Aviate, navigate, communicate. The most important thing is to fly the plane. Answering Viktor at that moment wasn’t necessary. He wasn’t offended. He was “crew.” He knew I had other priorities. When I did speak to him, I was clear about my intentions and what I wanted from him. It’s equally vital as a leader that you speak with your people in a way that not only can be understood by them, but just as importantly, cannot be misunderstood.

Fundamentally, successful airmanship is all about leadership skills. It can be easy to forget this when learning to fly and then, throughout your career, focusing on the day-to-day technicalities involved. But having sat both in the pilot’s seat and the C-Suite, I know that I’d have great confidence in hiring a pilot for a leadership role. Pilots know how to get the job done… every time!

I hope you enjoyed Steven Myers post as much as I did.

If you are interested in finding out more about his adventures in Russia, including espionage and intrigue, then consider picking up a copy of his book, available as a hardcover, e-book or audiobook: Cross Winds: Adventure and Entrepreneurship in the Russian Far East.

In fact, I’ve picked a copy of the ebook for myself as a fun read for my end-of-year break.

I have no comment to make… I just want to give a dozen thumbs up at that landing. That wasn’t winging it, even though it probably looked like it from the outside. It was a calculated course of action with several possible events already planned for. Bravo.

Great writeup, thank you.

This is indeed a great feat of piloting. However, what writer calls leadership is actually management — and Theory X management (close kin to autocracy) at that. What he’s writing about is top-down, everyone-in-their-place management; I’ve seen cogent arguments that the best-led people say, with justification, “We did it ourselves!” He’s not an example of the sort of failed CRM that Sylvia has shown in several articles, but I’d hate to work for him.

Thanks for your thoughts Chip. The challenge of leadership is in finding the appropriate balance between getting the job done and building consensus, depending on the situation. That’s true in business, aviation and in military operations. Most of my jet experience has been in crew situations where CRM was paramount. Nothing I’ve talked about in the article was meant to discount the value of CRM. But, CRM is a management “tool.” When confronted with a business crisis, an aviation emergency, or a tactical military situation the CEO, pilot-in-command, or battlefield commander may not have the luxury of time for consensus. The employees, the crew and passengers, or the troops are not interested in consensus in a crisis. The real test of leadership is the ability to lead when uncertainty is at it’s highest. We might quibble about the difference between crisis management and leadership. But, it may be more about semantics than substance. One of the key take a ways of the article is that effective leadership may prevent a dicey situation from becoming a crisis in the first place.

Great leadership inspires others to display followership. Nothing about that landing causes me to think, “I want to work for, or vote for, or have a beer with, that guy.” i have a friend who is a great leader, and i keep fearing he will ask us to rob a bank someday, ‘cos we’d do it. Myers appears to be a decision-maker, not a leader.

Congratulations on successfully pulling off a very difficult landing.

However, had you failed, and wadded up the aircraft (and possibly the personnel on board) you would have been (rightly, in my mind) excoriated for pushing through a landing wildly out of specifications for your aircraft – and why? ‘Cause you might have been a bit late? This is exactly the sort of ‘push on down, we’ll make it!’ attitude that has killed so many aviators (and their passengers) over the years, carefully and accurately documented nowhere better than this very website.

In short, you got lucky. Yes, luck does favour the prepared, but face it – you landed an aircraft in far more crosswind than it was specified for – and got away with it. You got lucky.

You had alternates – you just “didn’t like them”. So you risked it all – and, that one time, got lucky.

No. That was skillful piloting, but it was not good piloting. A good pilot would have landed with much more safety at your alternative.

I do not think this is a good lesson to take into business, either.

Thank you,

Jon

You are an amazing pilot, writer, and former boss.

For the naysayers here, read his book and then think again.

If that be the preview, I believe I have better things to spend my time reading. J.