The teenager who flew to Moscow

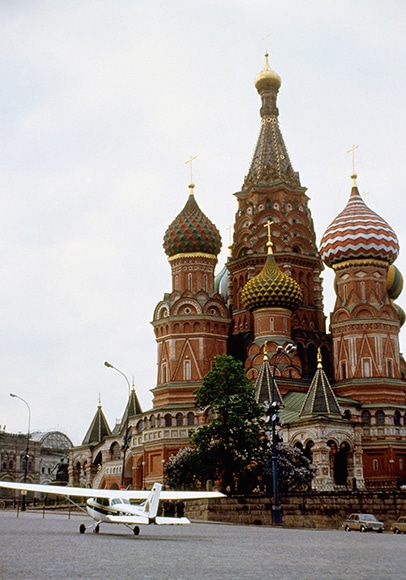

28 years ago, on the 28th May 1987, a 19-year old German flew a Cessna 172 to Moscow, taxi-ing straight into the Red Square.

At the time, the airspace around the Soviet Union was closed and fiercely protected. Just four years earlier, Korean Air Lines flight 007 was shot down by a Soviet Su-15 interceptor. The commercial flight departed Anchorage, Alaska normally but about ten minutes after take-off, it deviated to the north of its assigned route and maintained that heading for the next five hours, leading it on a course heading for the Soviet island of Sakhalin.

General Kornukov (to Military District Headquarters-Gen. Kamensky): …simply destroy it even if it is over neutral waters? Are the orders to destroy it over neutral waters? Oh, well.

Commander Kamensky: We must find out, maybe it is some civilian craft or God knows who.

General Kornukov: What civilian? It has flown over Kamchatka! It [arrived] from the ocean without identification. I am giving the order to attack if it crosses the State border.”

The Soviet Union initially denied having anything to do with the missing airliner but soon after admitted that they had shot Korean Air Lines flight 007 down. They claimed that the airspace infringement was a deliberate provocation by the US and that the Korean commercial jet was on a spy mission.

An investigation by the ICAO concluded that the deviation was caused by a navigation error and the crew never noticed that they had flown off course.

Commercial aircraft managed to avoid infringing Soviet airspace after that …until Mathias Rust.

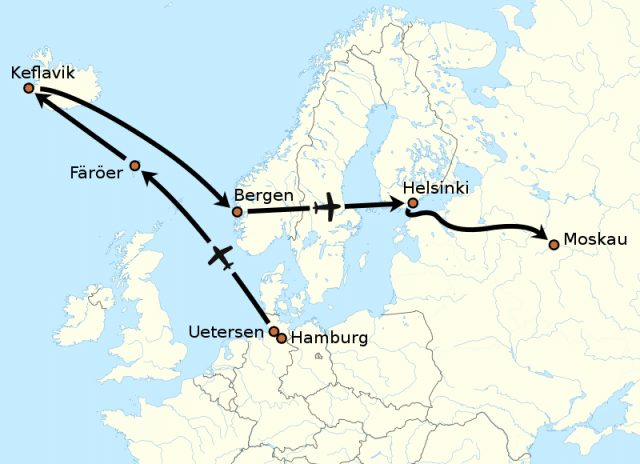

Mathias was a West German teenager who was described by his mother as a dreamer who was obsessed with flying; he’d spent his allowance to fund flying lessons. In June 1987, he’d flown a total of 50 hours in flying lessons. He rented a Cessna 172 which had been modified to hold auxiliary fuel tanks and spent a fortnight flying around Northern Europe, stopping at the Faroe islands, Keflavik in Iceland and Bergen in Norway. On the morning of the 28th of May, he flew to Helskini-Malmi Airport in Finland and refuelled. He filed a flight plan to fly direct to Stockholm in Sweden, around 500 kilometres (300 miles) to the west. Ten minutes after take-off, he changed his heading to the east and followed the busy Helskini-Moscow route, refusing to talk to increasingly frantic air traffic controllers.

He disappeared from their radar. The controllers believed that he had crashed and immediately reported the incident as an emergency. An oil patch was sighted near the point where the last radar return had come from and the Finnish Border Guard was sent to the scene where they tried, without any chance of success, to find the boy and his plane.

Meanwhile, Mathias had crossed the Baltic Sea and was flying over Estonia. He turned towards Moscow and at 14:29, he appeared on the Soviet Air Defence radar. He did not reply to any attempts to contact and three military divisions with surface-to-air missiles began to track him. The military went into alert and two fighter jets were scrambled to investigate. Rust recounted later that he saw an aircraft with a red star flying so close that he could see the pilot wearing a helmet and oxygen mask. But he was sure the Soviet military would not shoot, after the political scandal of the Korean Air Lines flight 007 incident. “I was very scared at that moment, because I didn’t know what they would do. But when I set out, I didn’t believe they would shoot me down. I thought maybe they would force me to land before I got to Moscow.”

He continued flying.

The pilot of the MiG-23 reported that he’d seen a white sport plane, which he described as similar to a Yakovlev Yak-12. He asked for permission to engage, which was denied. The senior officers on the ground appeared convinced that the fighter pilot was mistaken. The Cessna 172 disappeared into the clouds while the officers argued about what, if anything, was out there. A commander in the national air defence system came to the conclusion that it was geese. He was spotted a few more times but various mishaps meant he remained undetected as an intruder, including a control officer assigning all traffic in his area friendly status because inexperienced pilots often forgot to set the correct IFF designator settings.

Mathias flew straight to Moscow. He’d studied a map of the city before his trip but once over the city, he found it difficult to get his bearings. He decided that landing in the Kremlin was too dangerous and flew to Red Square. He circled a few times to try to scare away pedestrians so that he could land, but it didn’t work. He landed on a bridge near the St. Basil’s Cathedral.

There were normally heavy trolley wires strung over the bridge but they had been removed for maintenance that morning. He landed safely and taxied past the cathedral and into the Red Square.

Tourists and Muscovites gathered around him. They thought he was part of an airshow. “When I got out of the plane, there were about 200 people around me. When they saw I didn’t speak Russian, some of them spoke English, and I told them I was on a mission of peace.” The local police and soldiers had no idea what to do with him and couldn’t understand why he didn’t have a visa. Meanwhile, Mathias signed autographs.

He spent an hour at Red Square before the KGB appeared, never seeming to understand that there might be issues with his unexpected arrival. Mathias told them that he wanted to meet Gorbachev. Instead, he found himself under arrest.

He was held until his trial which began three months later. There, he was sentenced to four years labour for breaching the Soviet border, disregarding aviation laws and malicious hooliganism. He served 14 months in Lefortova prison, sharing a cell with an English-speaking prisoner, before he was released as a goodwill gesture to the West. He returned home to Germany in August, 1988. He never flew again.

He also never got the chance to meet Gorbechev, however the Soviet leader used the opportunity to move against the defence minister and the commander of Soviet air defence forces, calling the incident a national shame.

Matthias Rust lands his plane in Red Square – May 28, 1987 – HISTORY.com

The repercussions in the Soviet Union were immediate. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev sacked his minister of defence, and the entire Russian military was humiliated by Rust’s flight into Moscow. U.S. officials had a field day with the event–one American diplomat in the Soviet Union joked, “Maybe we should build a bunch of Cessnas.”

[…]

One Russian spokesperson bluntly declared, “You criticise us for shooting down a plane, and now you criticise us for not shooting down a plane.”

In 2009, Mathias was working as a professional poker player. That makes so much sense. You’d have to be pretty good at bluffing to carry on flying into Russian airspace with two fighter jets alongside you trying to make contact.

Twenty years later, he told Danmarks Radio, “I think I would advise everyone to think twice before doing something like that. On the other hand, if someone is convinced about something, they need to do it.”

A great story, thanks Sylvia for publishing it again.

Mathias Rust had incredible luck surviving. The luck sometimes is with the totally inexperienced.

He also did demonstrate piloting- and navigational skills well beyond his level of experience. But I don’t think that he will ever be granted a pilot’s licence again. He also demonstrated an extreme inclination to take risk, not a good character trait in a pilot.

Sylvia, I don’t know what co-incidence. I too had published an article almost of the same contents on Mathis in my blog and the organization I run. “Plane Spotters Kerala.

Any way interesting to read. Thank you for publishing it.

Regards,

Prakash

Cockpitvoice.worldpress.com

A lovely story.