The MS Estonia 1994 Ferry Disaster Revisited

On the 28th of September 2020, a Swedish documentary called Estonia–The Find That Changes Everything made headlines around the world when they claimed to have found new evidence on the 26-year-old case of the sinking of the MS Estonia.

On the 28th of September 1994, The MS Estonia, a cruise ferry operated by Estline, sank while crossing the Baltic Sea on route from Tallinn to Stockholm. The ferry was carrying 989 people (186 crew and 803 passengers). The crew declared an emergency and various vessels in the area went to offer assistance but the weather was rough and the other ships on the Baltic were unsure of Estonia‘s position.

You can hear the complete radio exchange with subtitles here:

The ship disappeared from radar around 01:50. The first of the ferries that had diverted to help arrived at 02:12 and quickly made the seriousness of the situation clear. Meanwhile, although life rafts had been released, they were “wet” which meant that the passengers had to jump into the storming sea and swim to the rafts. In all, 138 were rescued from the Baltic; with some spending over six hours in 11°C water.

The sinking of the MS Estonia was the largest maritime disaster to happen in the Baltic Seas during peacetime and the second-largest European maritime disaster in peacetime, with only the Titanic holding a higher death-toll. Only 94 bodies were recovered of the 852 who lost their lives.

This took a political toll on the country which was only just beginning to find its feet after fifty years of Soviet occupation. The Estonia was referred to as Death ferry and many questions were raised about Estline’s operations and Estonia’s oversight.

The president of Estonia, Lennart Meri, was only the 2nd president Estonia had ever had, the first having held office from 1938 to 1940. In the weeks after the disaster, he expressed his frustration with the media portrayal of the situation. “Estonia is the most successful state in central Europe. Is the fact of this ship going down somehow a symbol of our nation’s fate? No.” And then, more chillingly, “The sea from time to time needs sacrifices. This is very deeply rooted in our culture.”

When I first arrived in Estonia, I was immediately intrigued by this case and, although there were no planes involved, I decided it would make for an interesting post for Fear of Landing. Within a week, I’d realised that this might not be possible. Here’s what I wrote to a friend at the time:

I’ve only started looking at this but the outline is already vast — this isn’t a post, it’s a book! There are multiple causes (design flaw, mechanical issue, bad decisions by crew, rescue failure) which led to over 850 fatalities (138 rescued). There’s political issues galore, especially considering that it was just three years after Estonia regained independence. And the case is surrounded by AMAZING conspiracy theories, made worse by the fact that it is illegal to dive at the wreck or even approach it, but only if you are Estonian, Finnish, Swedish, Latvian, Polish, Danish or British. This means that it isn’t illegal for me as a German citizen. It makes me want to charter a boat and go see!

The sinking of the MS Estonia turned out to be pivotal for maritime safety, initiating changes which had existed in the aviation world for decades, including passenger manifests, improved crew training, ramp inspections (although they aren’t called that) and a closer look at evacuation procedures.

Estonia, Finland and Sweden formed a Joint Accident Investigation Commission to investigation the disaster, which concluded that what we would call the probable cause was the failure of the bow visor locking devices which failed in the stormy conditions as a result of faulty design. Contributing factors were slow reactions from the crew, lack of clear evacuation alarms and instructions on the listing ship and a slow rescue response.

The Swedish Accident Investigation Board and the Accident Investigation Board of Finland also released their own reports that same year.

In 2004, Sweden commissioned an investigation after rumours that the ferry had been secretly and illegally transporting Soviet military equipment to Sweden. A retired customs officer said that he had been given specific orders not to inspect specific vehicles on the ferry. It was known that Russian troops departing Estonia were selling military equipment, weapons and ammunition to anyone with the money to buy it. The last Russian units left Estonia in August 1994, a month before the disaster.

The Swedish investigation confirmed that non-explosive military equipment had been onboard the ship on the 14th and the 20th of December 1994. The Swedish Ministry of Defence stated that there was no military equipment on the ship on the 28th.

In 2006, Estonia held a further investigation to answer open questions about how the ship managed to list so badly and sink so rapidly. The wreckage has been designated as a final place of rest for victims of the disaster, which means that it should not be disturbed. Dives to the wreck are explicitly prohibited. This is fairly common for wrecks and mass graves; the Geneva Convention stipulates that the dead should, where possible, be buried in individual graves that are properly maintained and marked. However, where that is not possible, customary international humanitarian law holds that all possible measures will be taken to prevent the dead from being despoiled.

The report concluded that it was not possible to confirm what caused the Estonia to sink without direct access to the wreck, which lies between the Estonian island of Hiiumaa and the Finnish archipelago of Turku.

I started collecting additional material, including many many studies on maritime safety and the survival aspects (interestingly, the disaster is a large part of the evidence that men are far more likely to survive a maritime event than women), PTSD, indications of blasting on shipbuilding steel, Crisis Intervention in Finland and the human factors which link the Titanic, Estonia and Costa Concordia.

This was obviously way beyond the scope of a Fear of Landing post and although I was briefly tempted to spend a year or two or three investigating the case thoroughly and writing a book on it, I regretfully decided that I was not the right person to take on the project, especially as a number of books and documentaries already exist.

Earlier this year, an Estonian petition was put forward to change the treaty barring access to the site so that the official results could be investigated. Almost two thousand people signed the petition. Many of the relatives of the victims, both in Estonia and in Sweden, question the conclusion from the original investigation.

The Estonian government formed a working group to deal with the petition. They were to report back by the end of March… but by then, of course, the world found itself in the grips of a pandemic. A twenty-five year old wreck was no longer a priority.

That brings us to the present. The Swedish documentary team have shown footage that they took of the wreckage. The first episode of the documentary was released on Monday to coincide with the 26th anniversary of the disaster.

The footage was taken using an autonomous underwater vehicle which explored the site much like the devices used to map the seafloor during the search for Malaysia Airlines flight 370.

About a year ago, the Finnish Border and Coast Guard said that a coast guard vessel had confronted a vessel, the Fritz Reuter, which they believed had dispatched a diving robot into the sea. The site is in international waters although within Finland’s economic zone. The press reported that under international law, disturbing the site is punishable either by a fine or a two-year jail sentence.

However, the dive was carried out from a German registered ship. Germany did not sign the 1995 treaty to maintain the sanctity of the site, which means that German ships are not bound by the treaty. The documentary team argues that they were not prohibited from visiting the site or diving at the wreck. However, two of the crew were Swedish nationals, including Henrik Evertsson, the director of the documentary. They may still be prosecuted for violating the sanctity of the grave.

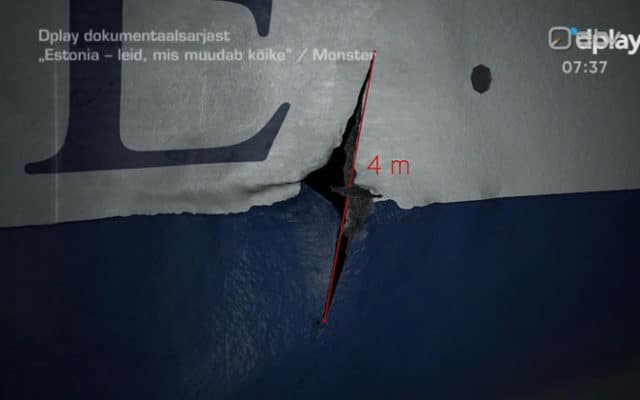

The footage from this dive clearly shows a four-metre hole ripped in the ship’s hull.

Over the years, there have been continual accusations that the governments involved have colluded to cover up the truth about the disaster. There are a number of English language pieces on this, such as Lies and Truths about the M/V Estonia Accident, The Sinking of MS Estonia: The Swedish Radical Right’s Favourite Conspiracy, MS Estonia – Still Doubts Over Official Story 24 Years After the Biggest Maritime Disaster in Europe Since WW2 and Ill-fated Estonia Ferry used for Weapons Transfers

Some of the survivors have said that they heard loud bangs about half an hour before the ship sank, which has been taken to mean that there was an explosion on the ship, which the official report denies took place.

The documentary claims that this hole in the ship was the true cause of the disaster, rather than the failure of the broken bow visor.

Margus Kurm, who led the Estonian investigation in 2009, says he thinks the hole must have been caused by a collision with a submarine. The hole is under the water line. The ferry was not off-route. There were no other boats known in the area and no reports of damage. None of the survivors mentioned seeing any other vessel. His theory leads to a number of hard questions. What was a submarine doing there? Why was this never reported? And did the investigators at the time know about it?

The senior Estonian foreign ministry advisor, Mart Luik, on the other hand, argues that the hole in the hull most likely happened when the ship struck the seabed. The documentary describes the seabed in the area as sandy but Luik says he’s seen the unedited footage where it is clear that the area near the hole in the wreckage is in fact very rocky. In the new footage, you can see the word Estline. In the description of the divers’ footage taken in December 1994, Luik says there is a reference to damage and a crack near the E of Estline. He has asked the filmmakers to show the entire underwater footage so that people can see the context. However, he agrees with Kurm that a full inquiry is needed.

The interior minister, Mart Helme, believes that the MS Estonia collided with another vessel and says that the only way to put the speculations to bed is to study the ship in detail. It would cost over €100 million to recover the wreckage, while an extensive underwater survey would cost only between €5 and €20 million, depending on whether they use robots or human divers. The ship lies 80-85 metres underwater (around 275 feet) and could be scanned using sonar and followed up with an autonomous underwater vehicle. This is more likely to be within Estonia’s budget although they are hoping to combine forces (and costs) with the Swedish government.

Conspiracy theories are taken rather more seriously in Estonia than in other places that I’ve lived and, it has to be said, often with good reason. There are valid concerns that the original joint investigation was sloppy with little or no public oversight. Some believe that the investigation was simply there to confirm the original theory that the disaster was caused by the broken bow visor. There’s evidence that the 1994 video footage was edited to remove sequences which included human remains. It is certainly true that the original VHS tape was copied badly, leaving many images murky and unclear. Although the official government line is that they have full confidence in the final report of the International Commission of Inquiry into the incident, everyone agrees that this time, the conflicting evidence cannot simply be ignored as not relevant.

The prime minister, Jüri Ratas, has said that he’s informed Finland and Sweden that an underwater investigation must be carried out. Estonia, Ratas said, will take the lead in ensuring that a supplemental investigation is independent, transparent and trustworthy.

It may be that the original report was correct in its conclusion, if not in its investigative techniques. Certainly, there is plenty of evidence of what could and should have been done better, both in terms of the maintenance of the ship and the ability to quickly and safely evacuate the ferry in the open seas. But there are enough open questions to make it worth another look at the seabed. I find it hard to believe that the relatives of the victims, many of whom signed the petition asking for more information at the beginning of the year, will feel that this is disrespectful.

I am planning on revisiting the original reports and following the new investigation as it progresses. I hope you will indulge my intermittent ferry posts interspersed with our usual aviation fare.

A diversion from the usual aviation material. Sylvia has laid a link, though: she is making a comparison between the oversight of shipping, both nationally and internationally, and the much stricter regulations that aviation is subjected to.

The international treaty seems to prioritise the sanctity of a shipwreck as being the grave of crew and passengers over the need to analyse the accident in order to find the cause, and finds ways to prevent a reoccurrence. Not to mention the possible political ramifications.

An interesting article!

Yes, this is fine. Your posts are always well researched and written, and interesting reading.

Somehow it doesn’t really feel like a diversion. Sylvia’s writing has always been more about making the hazardous safer than about aviation in particular.

She can just call the next book “Why Planes Crash and Ships Sink”.

Why Ships Sink does have a certain kind of ring to it…

Then perhaps the title should rather read “Why Planes Fall and Ships Sink?”

Harrow,

That is exactly what I meant. Sylvia has diverted from her usual aviation topics, but she makes the connection by pointing to the safety aspects, accident investigations, and the differences between the way they are conducted in aviation- and shipping accidents.

Personally, if I ever were to die in a ferry accident (I hope not !!), I would not worry about my “watery grave” being disturbed if it were necessary for the investigation. Certainly not if it could help to prevent another similar accident from happening.

I don’t understand the stance that avoiding disturbing the dead is more important than doing everything we can including sufficient research to protect he living from having the same thing happen again. That sounds ridiculous to me.

If private people were alowed to “investigate”, a lot of stuff would simply get stolen and sold off.

These rules don’t stand in the way of an official investigation, but they’re meant to be able to prosecute private people who go down there and just take whatever of value they can find.

You won’t be able to prove any of the thievery or prosecute on that, but you can deter them from going down to the ship in the first place.

I am really appalled with the non-formal approach to ship radio communications when compared to the rigid structure and wording for plane communications. Often without call sign, some with irrelevant information… probably this is an interesting point to dig into. This chatting (even in case of a Mayday situation) is general in the ship industry, or was it particular to this area? I will try to find the Costa Concordia comms

I will be interested to hear what you find. My general observation is that ships are larger-but-fewer (e.g., I was on a “small” cruise ship that carried 930) than airplanes; they also move much more slowly, and can slow down (or even stop if there’s an anchorage) without falling. Another question: are ships at sea subject to anything like the positive control and constant monitoring of planes over or near land? An absence of transmissions from en-route centers would leave a lot of airtime free for more-casual communications.

Back in 1994, AIS (the naval equivalent to ADS-B) was not yet in widespread use, so it would’ve been difficult to monitor marine traffic for traffic control.

Marine radio transmissions suffer from the fact that there’s usually not a direct line of sight between the stations (much easier to achieve in air-to-air or ground-to-air). As a consequence, a ship near the accident assumes control of the radio traffic.

Most aircraft accidents occur over land, within a clear jurisdiction; much of marine traffic happens in international waters, where it’d be difficult to impose any sort of authority on the captains.

This week, the blog becomes “Fear Of Sinking”. ;-)

The NTSB in the US also investigates maritime accidents, so there is a lot of common ground here, and I’m sure Sylvia is well equipped to write on it.

A professional video back then should have been recorded on Umatic, not VHS.

The claim that there was a collision with a submarine that hasn’t been acknowledged is extraordinary. It means that the nation operating that submarine has managed to keep this collision a secret, and has had a good reason for doing so; and that the crew were neglecting basic precautions. This claim requires extraordinary evidence; personally, I’m more inclined to see that tear in the hull as the result of the ship hitting the sea floor. But it would definitely be good to have a NTSB-style investigation and report on the exact sequence of events all the way to the ship’s final position.

In Germany, not too many years ago, a badly inspected fishing vessel (there were holes cut in the deck that were just covered up for the inspection) sank in the mouth of the Weser river with the owner’s son on it; and when the investigation team finally managed to send divers down, the computers on the bridge were missing. There are a lot of secrets buried under the waves.

https://de.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hoheweg_(Schiff,_1974)

Der offizielle Untersuchungbericht ist unten auf der Seite verlinkt.

Well Mendel, you certainly are right. But not only ships, aircraft too have disappeared over water, not to be found ever again – or in some cases decades later.

Sylvia certainly has chosen a challenge for her readers. Very few of us are competent to voice expert opinions, but on the other hand a comparison with aviation and some common sense seems to go a long way.

Mendel,

I skimmed through the Wikipedia entry that you suggested. It is about a fishing vessel, the “Hoheweg” that sank in the North Sea.

The wreck posed a danger to shipping and also to the environment because it had full fuel tanks, so it was lifted and brought to Bremerhaven where the wreck was subjected to an investigation. The conclusion was that a firehose, used for cleaning the deck, had somehow gotten overboard and wrapped itself around the propeller shaft. Without engine power, control of the cutter was lost and it capsized. Additional factors were that doors to cabin and wheelhouse were found open and modifications to the vessel that had not been approved led to a reduction in stability.

A sad story, but what is the relationship to the sinking of the Estonia?

And since we have broached the subject: Yes I can agree that free access to a wreck can lead to theft of objects on board, even disturbing evidence. But that can be regulated in maritime law. I am not familiar with laws dealing with ships that sank outside of territorial waters, but if access to divers can be restricted or even prohibited, surely another rule can be implemented, if it does not already exist, to limit access to official investigations.

If an aircraft comes down, the investigation will be conducted under the laws of the country where it crashed, but investigators of the country of registration, as well as experts from the manufacturers will be involved as well.

There are international laws and agreements; what is there to prevent something similar to be implemented for ships?

A prohibition on the grounds that the wreck is a grave and must not be disturbed is in my opinion not a really valid argument. An investigation has the potential of providing clues to what happened and how to prevent a similar accident from reoccurring. Relatives of the victims may well prefer to have a burial rather than a ceremony where they throw flowers on the water from the deck of a ship. The German authorities had no problem lifting the wreck, regardless of whether or not it might still have bodies on board.

I have the feeling that Mendel has this in mind when he put us on to the Wikipedia article.

The Hoheweg sunk in shallow waters close to the coast in German jurisdiction.

The mystery is that the captain’s body was never found, and we don’t know much about what the ship was doing because someone (who?) stole the computers. Why was it out in this weather? It’s possible that the hose was placed there intentionally as an act of sabotage or self-sabotage.

In aviation, when there is an accident on land nowadays, usually the investigators can gather a lot of information very quickly. In the marine realm, that’s a lit more difficult (as it is when planes crash over the sea), so that makes many of these these accidents more mysterious.