Alcock and Brown: Part 3

Last week, we looked at the teams and the aircraft who were competing to be the first to fly across the Atlantic.

Alcock and Brown arrived in St. John’s, Newfoundland on the 24th of May, a few days before the NC-4 completed the first aerial crossing of the Atlantic. The Daily Mail prize, however, was for the first “non-stop” flight in 72 hours or less (landing on the water was permitted); the prize was still up for grabs.

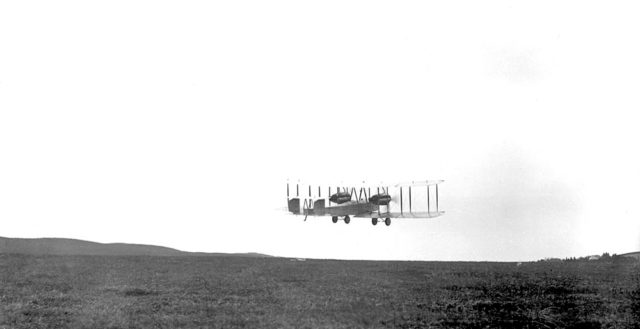

But it wasn’t that easy. The Vickers Vimy was a large twin-engined bi-plane and even to move the pieces required trees along the side of the main road to be felled. There were no hangers and no building in St John’s large enough, so the aircraft had to be assembled out in the open, in high winds and rain. And on top of everything else, all the best fields had already been taken; Alcock and Brown struggled to find anywhere that they could convert into a makeshift landing strip.

In the end, they found a large field between two hills: not optimal, but it would do. The ground crew removed fences and walls, blowing up boulders and pulling out trees in their attempts to level the ground. They managed to create a landing strip of 500 metres (about 1,500 feet) and flew the Vimy there from St John’s. It had taken about three weeks but now everything was ready… except that the weather was still too bad to make an attempt.

The following day, the 14th of June 1919, the weather improved and the forecast predicted better weather ahead. Alcock decided they should depart for Ireland before the others could set up for their own attempts.

No doubt inspired by the naval tradition that every ship needs a cat, Alcock and Brown both took toy cats as mascots with them for the flight. Alcock’s cat was black and named Lucky Jim; Brown’s cat was brown and called Twinkletoes. They also took some lucky white heather and a horse shoe, weight restrictions be damned.

The weight was of course a serious problem and I shouldn’t make light of it. One of the great limiting factors for long-haul flights was that the aircraft engines simply weren’t powerful enough to deal with the weight of the fuel which was required to make the flight. The Vickers Vimy was powered by two Rolls Royce Eagle VIII V-12 engines but as Steve pointed out in the comments in part one, having two engines increased the power but it also increased the points of failure. If either engine failed, the aircraft was no longer capable of flight.

In order to carry enough fuel to make the crossing, the gunner’s cockpit and the fuselage bomb bay had been converted into fuel tanks. After the modifications, the Vimy held 3,932 litres of fuel (1,039 US gallons) which would have weighed just over 3,000 kilos (almost 6,700 pounds). That increased the range to 2,440 miles at the cruising speed of 90 mph (144 km/h). The shortest route across the Atlantic was 2,000 miles.

The instruments were basic: an altimeter, an airspeed indicator, a fuel pressure gauge and a compass. I am sure Alcock must have had some sort of level indicator based on the conditions of the actual flight, but I couldn’t find any documentation on that.

The two men with their toy cats made ready for departure and departed shortly after lunch local time, which Brown noted in his logbook as 16:12 GMT.

It took them almost 300 metres of the 500-metre strip to get off the ground and even then, it was a close thing. Brown was not entirely sure that the Vimy was going to make it up, especially as the position between the two hills made the wind particularly turbulant.

Brown wrote about it later for the Royal Air Force and Civil Aviation Record, which was quoted in Yesterday We Were in America

Owing to its heavy load, the machine did not leave the ground until it had lurched, at an ever increasing speed, over 300 yards. We were then almost at the end of the ground tether allowed us… At times, the strong wind dropped almost to zero, then rose again in an eddying blast. Once or twice, our wheels nearly touched the ground again. Several times I held my breath, from fear that our undercarriage would hit a roof or a tree-top…When after a period that seemed far longer than it actually was, we were well above the buildings and trees, I noticed that the perspiration of acute anxiety was streaming down [Alcock’s] face.

We wasted no time and fuel in circling around the aerodrome while attaining a preliminary height, but headed straight into the wind until we were at about 800 feet. Then we turned towards the sea, and continued to rise leisurely, with engines throttled down. As we passed the aerodrome, I leaned over the side of the machine and waved farewells to the small crowd.

The main newspaper of St John’s reported that the townsfolk stopped in the streets to wave and cheer and the ships in the harbour all sounded their sirens.

Alcock and Brown officially crossed the coast at 16:28 GMT which started the timer for their crossing. Brown sent a morse code message to Mount Pearl Naval Station that simply said “Airborne”.

However, it immediately became clear that the forecast for clear weather over the Atlantic was mistaken; they quickly encountered clouds and fog. Then the radio died: it was powered by a wind-driven electrical generator but the propeller fell off about an hour into the flight. This also killed their intercom system which was meant to let them to communicate in the cockpit using throat microphones. They now had no contact with the outside world and the only way they could communicate in the noisy cockpit was to pass notes back and forth.

It would take another long post to talk about the navigation methods available to them but the key point is that a map does not help very much when over the open water. In order to stay on track, aviators were reliant on dead reckoning, which is that your distance equals the speed and time travelled. This system is still taught today although the existence of navigational beacons and GPS has made it largely irrelevant. The problem with dead reckoning is that it is so easy to get it wrong because it is difficult to know your exact speed or track. Every minor deviation of groundspeed or heading then compounds the issue and the cumulative errors mean that, within a relatively short time without landmarks or other means to determine your position, you can quickly end up miles away from your intended course.

This was why the Navy flight positioned war ships at 50-mile intervals: it gave the flight crew a clear set of landmarks to follow, effectively a very expensive breadcrumb trail. But Brown has no terrestrial landmarks over the open sea. All that he has is what he can see: the sun and the moon and the stars and the horizon. So in order to determine their position, Brown had to use celestial navigation, using a sextant to measure the angle between the astronomical objects and the horizon. He also had a drift indicator, which could help him to determine the wind speed and direction, in order to correct their heading and groundspeed.

However, he could not do either of these things without clear visibility of the stars and the sea. Alcock also needed a clear horizon for visual flight and in the weather, he struggled to keep the Vimy straight and level.

Things continued to go wrong. The exhaust pipe of the starboard engine broke off, overheating the area and risking a fire on the fabric covered fuselage. Then the battery-heated flying suits failed, leaving the two men with very little insulation against the cold ocean air.

Just after midnight, they finally had some good luck. Brown managed to get a view of the sky through a gap in the clouds. He used Polaris (the North Star), Vega and the moon for reference and was able to determine their approximate location and amend their track. But soon they were back into clouds. In the cold night fog, ice began to accumulate on the aircraft. Soon the pitot tube iced over, which meant that Alcock no longer had any indication of their airspeed, which is critical information for maintaining safe flight.

The inevitable happened: Alcock pulled up the nose to correct the Vimy from a descent but, with no view of the horizon and no airspeed, he overdid it and stalled the aircraft at 4,000 feet above mean sea level. The Vimy went into a spin. Alcock had no visual frame of reference and had no idea in which direction they were spinning or even which was was up.

As the Vimy descended, it broke out of the cloud at one hundred feet above sea level and the men found themselves looking sideways at the large cresting waves of the Atlantic. Alcock immediately recovered from the spin and amazingly, he managed to right the aircraft before impact, at just fifty feet above the water.

Alcock climbed back into the cloud, those 12-foot waves too close for comfort, and climbed to 7,000 feet, hoping to clear the cloud and fly over it. Again, ice started to accumulate on the aircraft, weighing it down and forming in the pitot tube and the engine intakes.

Alcock continued through hail and sleet until he reached 11,000 feet. They were still in the cloud and the ice was accumulating faster. I don’t know if Alcock knew it but he could not take them higher without risking hypoxia in the low atmospheric pressure above 12,000 feet. Certainly, he needed all his wits about him if they were to survive this flight.

The ice continued to accumulate. The starboard engine misfired, a sign that the engine intakes were being blocked by the ice. Alock cut the power to avoid damaging the engines and descended again, hoping to reach warmer air and break free of the cloud. They finally broke free of the cloud at 500 feet over the ocean, where Alcock returned the power to the engines.

The Vimy’s weight and balance was also slowly shifting as they used up the fuel which accounted for the bulk of their weight. The spring trimmer which had been installed to counteract this (a poor man’s precursor to MCAS, perhaps?) had failed and the aircraft became increasingly out of trim and nose down as they continued. Flying this close to the waves was dangerous with no real ability to manoeuvre. They stared out into the rain and low clouds, hoping to see the hills of Ireland.

Finally, at 08:15 GMT, they spotted land directly in front of them: two small islands off the west coast of Ireland. “The mainland was not visible until we were practically over it,” said Alcock afterwards. “And then only the hills.”

As they approached, however, they saw the masts of the Marconi wireless station, which meant they had a landmark that they could correlate to the map. They had reached Clifden in County Galway and were only ten miles off of their intended track. The journey from the Newfoundland coast to the Irish coast had taken 15 hours and 57 minutes, but they still had to land.

Alcock fired flares to direct attention to them and then found a flat green field and made his approach.

Unfortunately, it was not a field but a bog. As the Vimy touched down, the nose gear sank into the mud and the tail rose high, tipping the plane into the bog.

People soon gathered at the site of the crash landing. “Where have you flown from,” asked one. “America,” answered Alcock, to great laughter … they could not believe that this might be true. But soon it became clear that Alcock and Brown had indeed crossed the Atlantic, the first ever non-stop flight, which they achieved in just 16 hours and 28 minutes.

Mind you, Alcock did not sound very impressed at the time. “We have had a terrible journey,” he said.

The wonder is we are here at all. We scarcely saw the sun or the moon or the stars. For hours, we saw none of them. The fog was very dense and at times we had to descend to within 300 feet of the sea.

Some accounts of this flight include an episode in which Brown crawled out onto the wing, in order to clear the ice from the engine intake with his pocket knife. I’ve not included it because I don’t think it happened. There’s no mention of this in Brown’s log, which he updated every hour. Besides, climbing out of the cockpit and onto the wing in high winds in icing conditions is not something that a man is likely to survive. If he was not blown off the wing, the same icing that was covering the wings would be covering him and he had no source of heat in the cockpit other than his own body heat in a confined area. Add to this that Brown had been injured in the war and was lame in one leg and it is difficult to imagine how he could have pulled off a wing-walking stunt such as this.

Six months later, Alcock was killed when he crashed his Vickers aircraft on the way to the Paris Air Show. He was 27 years old.

Vickers and Rolls Royce agreed to donate the Vimy aircraft to the Science Museum. It can still be seen today, a hundred years after that incredible flight, at the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester. I’m sure Alcock and Brown would be happy to know it was in their home town.

Although the daring flight across the Atlantic was said to herald a new era of passengers crossing the Atlantic by air, in fact commercial passenger flights did not start for almost another decade and those were flown by airship.

True or not? It is said that Clifden was intentionally chosen for the landing site because of the Marconi radio station. Ireland, in 1919, still was part of the United Kingdom in its entirety and Clifden, now in the Republic of Ireland, therefore qualified to claim the prize. This claim was secured immediately by transmitting the message to London, thus preventing any other potential claim.

There is also the story that Alcock and Brown mistook the waving of people on the ground as a signal to land there, instead they were trying to warn the pilots that the spot chosen was soft and unsuitable; this fact of course was proven by the nose-over of the aircraft which was very badly damaged. But the pilots were not injured.

There still is a hotel in Clifden named the “Alcock and Brown”.

A minor comment on an excellent summary. The aircraft is on display at the Science museum at South Kensington in London, not Manchester.