ATC Heroes: A Super Bowl Save

This is the happy-ending story of a Cessna Cardinal flying back to his home base of Paris Airfield, Texas in bad weather when the aircraft experienced a complete electrical failure. I found this amazing story on the NATCA website and they kindly gave me permission to reprint it.

The New England Patriots’ stunning comeback win in Super Bowl LI on Sunday, Feb. 5, was a classic example of teammates working together to defy incredible odds. But for all the drama playing out in Houston, a bigger drama with deadly odds was playing out in the skies around the Dallas-Fort Worth area.

As the football game went into overtime, a team of more than half a dozen controllers at Fort Worth Center (ZFW) went into overtime to aid a pilot whose plane had experienced complete electrical failure. During the next hour, the teamwork and quick-thinking demonstrated by ZFW’s Bonham — and Dallas — area controllers helped guide the pilot to a safe emergency landing.

The assist involved a Cessna Cardinal that was returning to Paris Airfield in North Texas on a flight that originated several hours earlier in South Texas.

Bryan Beck, an operations supervisor at the center, remembers that evening vividly.

“It’s Super Bowl Sunday,” Beck said. “We had a lot of arrival traffic. I’m down to my last six controllers. They all have one hour left on their shift. This is the end of their day. Traffic levels have dropped.”

His team was easing into the end of their day, not expecting the adrenaline rush that was about to hit them. There were low IFR (instrument flight rules) conditions persisting in North Texas due to a front slowly passing through the Dallas-Fort Worth area. Paris airfield was reporting 3/4 of a mile visibility with 200-foot cloud ceilings.

The Cessna’s flight had been uneventful and its pilot had been cleared to land in Paris. But as controller Charlie Porter was briefing Phil Enis, his relief that evening, they noticed the beacon code of the aircraft reappear on the radar scope. That was not unusual if the plane had missed its approach and was going around for a second attempt. But the altitude indicator showed that the aircraft was climbing well above the missed-approach altitude of 3,000 feet to as high as 6,500.

Enis, who had assumed responsibility for the position, attempted to reestablish communications with the pilot without success. He then noticed the beacon code briefly change to code 7700 — indicating an emergency — and notified Beck.

“There’s a lot of unknowns in dealing with this situation,” said Enis. “We were fortunate that we reacquired him before he lost his transponder. We just had to surmise that he had an electrical failure. We knew ceilings were very low. Landing without electrical power would be very difficult.”

“We couldn’t talk to the pilot and we couldn’t see him anymore,” said Beck. “Unfortunately, in our business, that usually means you’ve lost the guy.”

Beck’s senior crew had committed themselves to landing the Cessna safely. And they had the experience to handle such a situation. Beck estimates that his controllers had 175 years of experience among them.

As Enis continued to broadcast on his frequency to contact the Cessna, controller Russell Smith at the radar screen next to Enis began broadcasting on the Coast Guard frequency trying to reach the emergency aircraft as well.

The 7700 emergency code appeared intermittently, then stopped completely. The target disappeared from the radar, still with no voice communication from the pilot. Operations Manager Michael Turner quickly began processing an ALNOT — an alert notice requesting an extensive communication search for overdue, unreported, or missing aircraft.

The controllers continued to try to contact the pilot, and Enis asked other aircraft on his frequencies to attempt to reach the Cessna pilot. Though having been relieved from his position, Porter remained to assist in the effort to aid the pilot in distress. The controllers then observed a faint blip return to the radar screen that appeared to be proceeding to the southwest along the previous track flown by the Cessna. Porter split off that radar sector to isolate the frequencies in an effort to reestablish communications with who he hoped was the Cessna pilot.

Over the next 40 minutes, Porter broadcasted dozens of times blindly advising the aircraft of its position to emergency airports and weather conditions that were favorable for VFR (visual flight rules) landing. He coordinated with Controller Hugh Hunton on possible emergency airports located just south of Dallas. Hunton, a private pilot himself, quickly began brainstorming with Porter on ways to contact the Cessna. The ALNOT had not yet returned any pilot information or contact number. Porter asked Beck to look up the Cessna’s tail number in the FAA Airman’s Registry.

Beck discovered the aircraft was registered to an individual in Paris, but the registry offered no contact information other than a mailing address. Nor did a call to the Flight Service Station reveal the pilot’s phone number.

Porter suggested Googling the pilot. Beck was able to identify the pilot’s name and discovered that he was a neurologist in Paris, but a call to the doctor’s office went directly to voicemail. Beck then searched for hospitals in Paris, turning up one result. Getting through to the hospital switchboard operator, Beck quickly explained the circumstances. The switchboard operator paused for a moment and then provided the cell phone contact information.

Porter called the pilot’s cell phone number several times, but received no answer.

“It was just frustration,” recalled Beck after the cellphone call failed to go through. “For 45 minutes we were trying every method that we have, but we’d exhausted everything. My heart drops because that avenue ran out.”

But Beck and his team persevered.

“You always fear the possibility of losing him,” said Enis. “It’s always in your thought process. We were just focused on helping him any way we could.”

“I felt positive the whole time,” added Porter. “If the avionics would have failed and we would never have seen him on the radar scope to give us a good idea this is him, it would have been a whole different outcome. I think we had luck on our side. You think that you can hopefully solve it in a positive way.”

Weather to the west of the Cessna’s position in the Dallas terminal area was improving, but in the aircraft’s presumed area, conditions were continuing to deteriorate. Options for an airport close by with VFR conditions were limited and time to reach the pilot was running out. The controllers had exhausted all attempts at regaining contact with the aircraft.

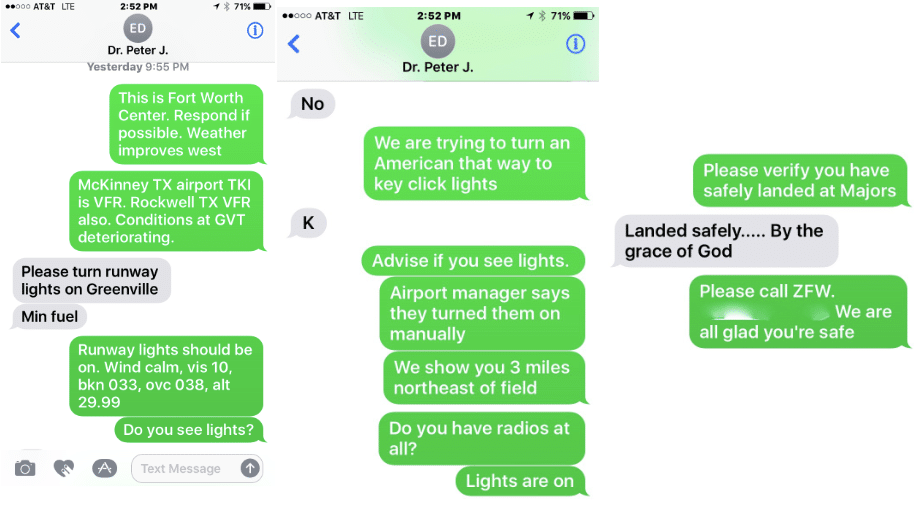

Enis, who had been relieved from his radar position at the end of his shift, remained to assist and brainstorm ways to assist the Cessna Cardinal. Enis asked for the phone number of the pilot so he could step out of the area and call the pilot himself. Beck remembered from his experience during Hurricane Ike in 2008 that cell phone calls sometimes would not go through, but text messages would. He asked Enis to send a text message to the pilot’s cell phone.

A minute or two passed before Enis returned to the center’s operational area: Contact had been made and the situation was dire.

Beck remembered how happy they were to make contact, “We got a hold of the guy. It was a pumping fists-type reaction.”

The plane had indeed suffered complete electrical failure, was flying on minimal fuel, and needed to land quickly. Beck asked Enis to remain in the area to help relay emergency airport information and weather information to the pilot via his personal cell phone.

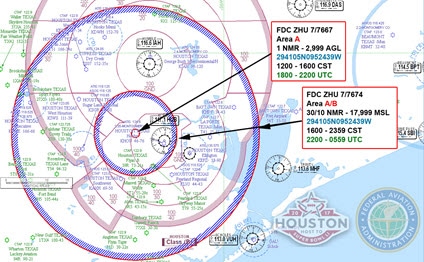

The aircraft was overflying Commerce Municipal Airport, a small emergency airfield located northeast of the DFW Metroplex, prior to contact being reestablished. But the lights at the airport were not on, and the pilot had no electrical power to activate the lights from the cockpit. This presented another dilemma for the controllers. Turner, the operations manager, realized that they would need to activate runway lights at the next available option, Greenville Majors Airport, southwest of Commerce. He asked the Dallas controllers and operations supervisor to begin working on turning on the lights for the Cessna.

Operations Supervisor Michael Clifford worked with controllers Hunton and Thomas Herd to contact Greenville security to turn on the airport runway lights, and also advised fire/rescue of the emergency aircraft inbound to the field. As the aircraft approached Greenville, the pilot notified the center that the runway lights were still off. Porter, still on the scene, first had an American Airlines flight in the vicinity activate the runway lights for the Cessna pilot, followed by additional pilots in the area.

The pilot lined up for Greenville Majors Airport and then circled to make an approach to the north. Clifford was on the landline phone with Greenville Fire Rescue as the plane made its descent and final approach to the airport. The Fire Rescue personnel reported that they saw a small aircraft land on the runway and were able to verify the tail number as that of the plane in distress. A few moments later, the pilot texted Enis: “Landed safely…by the grace of God.”

“If we could have thrown hats in the air we would have,” said Beck. “We were overjoyed. We all came together as one to be a part of something bigger than ourselves. It gave us all tingles.”

“The tenacity and professionalism displayed by the Fort Worth team was of the highest standard,” said Nick Daniels, NATCA ZFW FacRep. “Their example is indicative of the dedication by our controllers to work together and help maintain our portion of the safest airspace in the world.”

“As long as I’ve worked for the FAA, I’ve never seen the amount of teamwork displayed here with everybody — in the building, out of the building,” said Porter. “I was just honored to be with these other professionals. I probably won’t ever see that again in my career. It was just an honor to see the people work so well together.”

Later that evening, Michael Turner answered a call from the pilot of the Cessna. The clearly shaken pilot told Turner that until the text message from Fort Worth Center came through on his cell phone, he didn’t know if anyone knew that he was in distress. The pilot advised that he had at most a quart or two of fuel remaining.

The pilot returned home alive that night. Porter went home without ever mentioning the events of that night to his family. He says they still don’t know. Porter followed his usual routine and was in bed by 9 p.m. “I said my prayers, and I said one extra one: ‘Thank God this turned out the right way.’ Something was looking out for all of us.”

Enis was too keyed up to sleep.

“I did share with my wife what went on,” he said. “She knew that it was something that affected me.”

The adrenaline rush and his racing thoughts kept him up until 2 or 3 a.m.

When he arrived at his house that evening, Beck’s wife asked him if he had watched the dramatic end to the Super Bowl.

“You know what,” he told her, “I had a Super Bowl of my own tonight.”

On the 10th of January, the pilot got the chance to meet the air traffic controllers who got him down that night which was also featured on the NATCA website: Emotional Reunion as Pilot Meets ZFW Team That Helped Save His Life.

“It was really nice to meet the pilot we assisted and hear what he experienced,” Enis said. “I know that it was a tense situation at ZFW, but it pales in comparison to what he was going through. Hearing him describe how he texted his son to tell him goodbye, thinking he wasn’t going to survive the experience hit me pretty hard. It made me even prouder of the work the ZFW team accomplished. Getting him down safely is our job but the ‘outside-the-box thinking’ done that night is what made it possible.”

We’re all proud of you, ZFW. Good job!

You can read the whole story, including the thank you letter from the pilot, on the NATCA website. You know I’m a sucker for a happy ending but I think this is my new favourite.

The efforts of the air traffic controllers were superhuman. They deserve a Congressional Medal of Honour. Professionalis of the very highest order.

But also the pilot must be included in the honours list. To be totally lost, in IMC, in an aircraft without electrical power, without navigation aids nor communication, must have been a heart-stopping situation. Yet, he kept his cool and eventually landed safely.

Airmanship of the highest order !

And yes, Sylvia, I too love this story.

:D

can you try to do a summary report on a plane crash that happened in Amarillo Texas in the month of april 2017

Do you mean the Rico Aviation medical flight that crashed at night? Looks like a bad crash as the result of illusion. I’ll take a look (but I should mention that it can take a while, I have a lot of half-finished posts).

yes that is the one!, i have been curious as to what happened for a while, thank you

Awesome story.

Glad to hear it ended well.

If I were in that position, worried that nobody knew I was in trouble, I might have flipped the switch on my ELT. That is completely independent of the rest of my aircraft electrical equipment.

Good one.

I am not sure what the ELT could have achieved.

It would have sent a signal, a penetrating undulating sound on the emergency frequencies.

The purpose is to locate an already crashed aircraft more quickly and help to direct emergency services to the site of the accident. Which accident, fortunately, had not occurred. And in this case was not going to occur.

Under the circumstances, I do not think that it would have achieved much, but might have caused more confusion. And it would not have done anything to locate the aircraft other than having a rough indication of its (changing) position, which ATC already had.

The key to this situation and its happy outcome was the tenacity of the controllers who went way ‘outside the box’ in order to find a way of communication and the composure of the pilot, who still was thinking clearly enough to respond.

The 406 MHz ELT in a modern aircraft transmits a unique beacon code that is linked to the aircraft callsign. If ATC had previously been tracking a transponder with a known callsign, they might be able to identify the subsequent no-transponder primary radar track as belonging to the aircraft in distress.

Now that I’ve had a couple days to think about this (realizing, of course, that the pilot in question did not) another option is to fly radar triangles. A sequence of six 120 deg left-hand turns every 2 minutes will draw an equilateral triangle on the radar screen. That’s a standard way to alert ATC to an aircraft in distress with no communications. Right-hand triangles signal a receive-only condition.

I wouldn’t have thought of that. But to be fair, I doubt he was thinking about how to get ATC to locate him. The big problem he had was how to get to the ground with no instruments, in instrument conditions, at an airfield where the lights were off. Secondary to that would be somehow letting someone know that he was landing there.

(also now that I think about it without electrics I think I’d struggle to handfly a recogniseable equilateral triangle!)

The triangle is an old one, it used to be in the Jeppesen manuals, maybe it still is. And it would certainly have drawn the attention of ATC – provided that they still had access to primary radar.

I admit, having retired from active flying more than ten years ago, that some of the modern systems are not known to me.

But even a more modern ELT would, in this case, simply pointed to a moving target. And the same with the triangle: How to dispatch an aircraft to intercept and guide it to the runway?

Many years ago, ace pilot Neil Williams got caught like that in a Vampire jet fighter. A bomber guided him to the runway. On short finals, in landing configuration, Neil got caught in the wake of the bomber and flipped upside down. Still, he managed to roll to the upright position and landed safely. Not many pilot possess those skills!

The problem facing the pilot in this issue was that he was in IMC, little chance of being intercepted safely. At least, Neil was “on top”.when his radios failed.

PS Sylvia,

Not too difficult, as long as you still have an (artificial) horizon and a stopwatch. One minute straight, a 60 degree turn, etc.

I seem to remember light (slow) aircraft fly 2 minute legs.

Right or left, I forgot which, tells ATC if there still is reception (right, I believe) and left total comms failure.

ATC will in such cases also send messages on the ATIS especially if it is on the VOR freque ncy.

I never had to use it, it is a very old procedure, but if a pilot needs it, AND of course knows how to use it, it can be a life save.