ATC behind the scenes: VFR into IMC

One of the biggest safety hazards in general aviation is pilots inadvertently flying into instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) and losing visibility in the cloud. A private pilot who has not undergone special training for using instruments flies VFR (Visual Flight Rules), looking outside the aircraft. If the aircraft flies into cloud, the pilot loses visual context and struggles to keep control of the aircraft. In 2006, Flight Safety Australia highlighted the issue with the results of an in-depth study called 178 Seconds to Live, where 178 seconds is the average time that 20 VFR pilots on a simulator lasted before suffering from spatial disorientation and beginning to oscillate dangerously or entering a graveyard spiral. All twenty pilots who did the simulation lost control of the aircraft and would have not have survived the flight in reality.

Every year in the US, NATCA (National Air Traffic Controllers Association) holds the Archie League Medal of Safety Awards, in which air traffic controllers who have displayed extraordinary skill in critical situations are honoured. Last year, because of the pandemic, the awards were put off and they are now scheduled to take place in August (with the 17th annual awards following directly on from that in September). This means that I have to be quick if I want to report on the 16th Annual Archie League Medal of Safety awards before they are last year’s news!

Although readers of Fear of Landing will be well aware of the risks of flying into instrument conditions, this case, for which Randy Wilkins and Chris Clavin at the Fort Worth Center won the award for the Southwest Region, gives an interesting look at VFR flight into IMC as experienced behind the scenes at Air Traffic Control.

Randy Wilkins is clearly one of us: he reads air safety investigations in his spare time and has gone through all the situations celebrated in previous Archie Awards. He also watches YouTube pilot videos dealing with VFR incidents and says that reading and watching these incidents has helped him understand the importance of the controller staying calm and focused.

You watch a video and think, ‘well, what would I do? Would I know to say that? Would I know to think about this?’ So I really fall back on those replays. If I was a pilot, I would think, ‘if that was me, what would I want to know, and what would I want somebody to say to me before I did this?’ The worst thing you hear about is people getting disoriented and flipped upside-down. The likelihood of getting disoriented in clouds if you’re not used to it is pretty high.

At the Fort Worth Center, they monitor the civilian emergency frequency, 121.5 in case of any distress calls. The frequency is also known as Guard as aircraft are asked to continuously “guard” the channel, listening out for requests for help. This is also the channel that the military would use if intercepting an aircraft and can be used by controllers to speak to aircraft inadvertantly entering their airspace (and thus not speaking to the correct control centre).

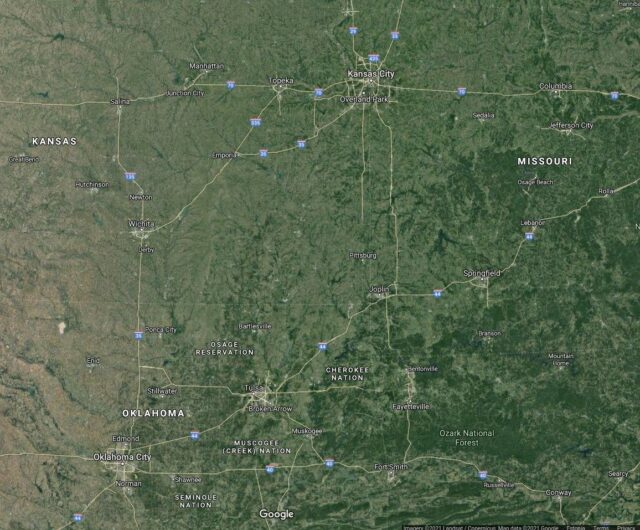

On that day, the VFR pilot of a 53-year-old Cessna 150H registration R23258 was flying at the edge of the Kansas City Center airspace, between Oklahoma City approach control and Tulsa approach control. He flew into bad weather and found himself in instrument conditions.

He was not trained for this: VFR pilots use visual contact with the ground and the horizon to judge their attitude rather than relying on the instruments. He couldn’t see anything but cloud and wasn’t sure where he was. Not knowing who to talk to, the pilot used the emergency frequency to report his situation. A Southwest Airlines pilot immediately responded to try to help the pilot work out his location.

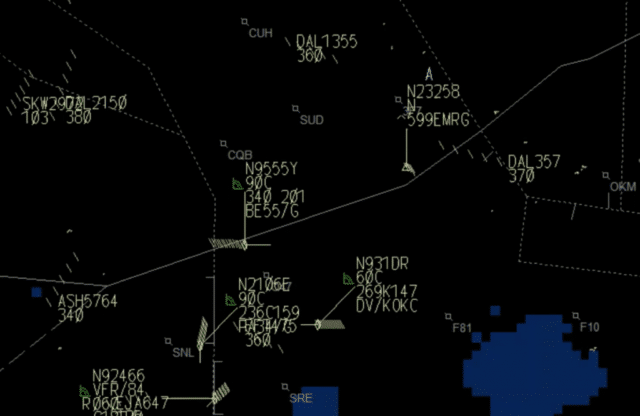

The controller at Forth Worth, Randy Wilkins, heard them speaking and asked the pilot to contact him on one of the Fort Worth frequencies. He was able to identify the aircraft on radar and marked it with the letters EMRG, so any other controller who saw the aircraft on radar would know that the pilot was experiencing an emergency.

The pilot was struggling to maintain his altitude and didn’t have enough power to climb well. The pilot quickly became frustrated and began to fly in circles, not sure where to go or what to do. Wilkins had his hands full trying to keep the pilot calm; both knew that the odds for a VFR pilot in instrument conditions wasn’t good.

Another controller at Fort Worth, Chris Clavin, had also overheard the call on the emergency frequency. He was near the end of his shift and was able to sit down with Randy Wilkins to support him in dealing with the emergency. The most useful thing he could do was find solid information that Wilkins could pass on to the pilot. He initially tried to find out if there were any airports nearby in clear weather so that the pilot could fly in visually.

While Randy’s dealing with talking to the pilot, I was just trying to get the most up to date weather information that I could between Stillwater, Kansas City Center, Oklahoma City Approach, and Tulsa Approach to see if they had any guys going VFR in the airports around there.

I was just trying to make sure that Randy didn’t have to do any coordination. It was my job to make sure he could focus on the pilot and I’ll take care of all the other stuff.

However, the weather wasn’t clear until west of Oklahoma City and the pilot only had a quarter of a tank of fuel left. Wilkins did his best to keep the pilot flying safely, reminding him not to look out the window but at his instruments and that he needed to focus on keeping his wings level and his airspeed up. He later said he could see that the pilot was rapidly getting the hang of it.

You could see him going through the process of learning how to fly, either on his instruments or however he was doing it. You could see him getting better and better at taking control of his aircraft. That might have saved his life – the 10 minutes he had to get used to flying in a manner like that, rather than saying, ‘I’ve gotta get through the clouds now.’ That’s how it looked to me.

Clavin found that Chandler Municipal Airport in Oklahoma had a cloud ceiling of 900 feet — not great for visual flight but better than any of the other airports within range. As the pilot made his way to Chandler, he descended through 2,500 feet and the controllers lost radio communications. All they could do was sit and wait for a phone call to tell them that the pilot had landed safely. Well actually, as Clavin points out, all they could do was sit and wait and keep working.

You don’t want to think the worst, but there’s other things going on in the sector that we had to take care of. It felt like 20 years before we finally got the update that he was on the ground.

The pilot landed safely at Chandler Municipal Airport. You can listen to the original radio calls and an interview with the controllers on the NATCA Podcast:

Both Wilkins and Clavin were grateful to have been chosen for the Archie League Medal. Wilkins sees it as a chance to pay back the training he has received from previous winners.

To be categorized like that is an honor, and I really hope that people can take it and learn something from it, because that’s really what this is all about. It’s about honoring the controllers that did a good job, but I try to use it as a training tool to say, ‘here’s what happened and this is what you can do if you get into this situation.’ That’s what I really hope comes out of it.

As we usually look at crashes and flights gone wrong, I found it very interesting to follow the VFR flight to a happy ending and especially the chance to hear about what the scenario is like from the point of view of Air Traffic Control.

It is so heartening to read articles like this. In my experience, I guess that the large majority of Air Traffic Controllers are superb professionals. They – as a group all over the world – have saved countless lives.

I have never tried this before, but I was once told that if a pilot of a Cessna 150* finds him/herself in IMC and is suffering from the onset of vertigo, one way of getting down to a survivable crash is:

– Close the throttle,

– Trim all the way back,

– Extend full flaps,

– Let go of the controls, don’t touch anything.

The aircraft will porpoise and wallow all the way down, not inverted, to the ground at low speed.

With luck, it may break cloud before “hitting the deck”, with sufficient room to resume control. Otherwise the impact should be survivable.

CFIT, a high speed impact, will not be so gentle.

Warning: “Don’t try this at home!”

I don’t know if there is something similar applicable to other types of aircraft.

After 8 years of flying VFR round the Scottish Highlands for pleasure, I have retired but it’s always been and still is on my bucket list to try IFR just to see if I could do it! I feel I could manage with the artificial horizon and the turn and bank indicator. Maybe one day I’ll get around to a trial flight.

In my days, basic instrument training was done with a hood, made of transparent plastic, over the head that limited the trainee’s view to the cockpit only. The training included “limited panel”.

For this, the instructor stuck a circular piece plastic or cardboard with a sucker cup on the artificial horizon, leaving the student with ASI, VSI, directional gyro, altimeter and the turn and bank (which actually should be called “turn and slip”) indicator. We were taught timed turns and more advanced patterns that included timed turns with timed climb or descent to another altitude.

The only time when I had vertigo when flying IFR actually was when I thought that I had enough visual reference to discontinue an ILS approach by going “visual”. In restricted visibility because of haze and a low sun, a road that bisected my flight path at an angle became a false horizon.

My training took over: I reverted to my instruments.

Steve, there is nothing magical about IFR flying. Just good training.

BTW: I don’t know if it has been phased out, but in my time there was the possibility to fly VFR in IMC in the UK. Bizarre. I remember pilots who had an “IMC-rating”. And once, flying in IMC, under IFR but outside controlled airspace, I was asked by the flight information service if I was under IFR or VFR. Where I came from (the Netherlands in those days) it simply would not be legal to fly VFR in IMC.

But, as with Brexit, the UK likes to do things its own way. In the UK, the quadrantal system of vertical separation remained in place for flights outside controlled airspace. I wonder if that is still the case.

I was a military AT controller, long since retired. There were many times on watch when the weather was not good enough to launch the fleet, during these times, the more experienced controllers would pose scenarios, usually about the operated aircraft and their peculiarities when in emergency situations and teach the newbys some important points. This sort of training was encouraged on each base I was posted to. It is nice to see the Americans recognising their controllers, don’t think there is anything like it in the UK.

While VFR into IMC is indeed a serious hazard not to be underestimated, the common “178 seconds to live” reporting is wildly over-stated hyperbole, probably owing to a long game of “Chinese whispers”.

The original results come from a study by the University of Illinois on behalf of the AOPA Foundation (now the Air Safety Institute), intended to devise a practical curriculum for teaching non-IFR pilots to recover from inadvertent VFR into IMC.

This much is true: The average time it took from a student encountering simulated IMC until they entered an incipient dangerous flight condition was, indeed, 178 seconds. The details around this experiment, however, are commonly either omitted or misreported entirely. Some highlights:

The experiment involved 20 subjects, chosen specifically to be representative of an average private pilot with no simulated or actual instrument experience. Not “none since primary training”; none at all. (This was before 3 hours of instrument training was a requirement for obtaining a PPL.)

The experiment was conducted on a Beechcraft Bonanza C35, chosen because it was the most complex single that a non-IR pilot was likely to fly. Only two of the subjects listed any time in a Bonanza, and none had flown it solo. Only 3 subjects seem to have had any complex experience at all.

The aircraft was made to simulate basic VFR instruments of the time plus a turn coordinator. The AI, DG, and VSI were covered for the duration of the experiment.

Seven of the subjects had less than 40 hours total time. Only three had logged more than 500 hours.

Time until entering an incipient dangerous flight condition ranged from 20 seconds to 480 seconds. The average was indeed 178 seconds.

Following 4 periods of instruction in the recovery technique, during which the subjects logged between 1.5 and 3 hours of instrument time, the recovery success rate rose to 59 out of 60 tests. In the one test where the success conditions were violated, the pilot had entered a gentle descent, but controlled flight was maintained and it was considered that even if it it had resulted in CFIT, the resulting crash would have been survivable.

The results of the “178 seconds” experiment are almost universally reported as a dramatic “you will die in less than 3 minutes if this happens to you”, which I’m concerned does more to discourage pilots from even attempting to recover if they ever find themselves in that predicament.

In reality, this was an experiment very much testing the absolute worst-case scenario, and the main takeaway seems to be that it is extremely survivable with a little training and preparation.

Some further reading:

https://groups.google.com/g/rec.aviation.student/c/IwgNPpKfpBs/m/BM8kKyUxR8QJ

https://www.aviationsafetymagazine.com/airmanship/survive-inadvertent-imc-the-old-fashioned-way/

When I learned to fly (1973-74) some very basic instrument flight work was part of the course — but I couldn’t tell you whether that was required, or standard, or just something the USAF-related school did for extra safety. (The instructor did NOT blank out the artificial horizon — that would have made the process a lot harder, and possibly given a pilot in IMC trouble the wrong idea about how handle the situation.)This pilot might or might not have had a little experience under the hood, making the controllers’ task slightly easier — but that could have been years before. Kudos to both controllers for keeping the situation under control and finding a solution — and to the pilot for listening instead of losing their head.

Roger, ask any pilot who has been in need of a helping hand from a competent AT controller; you will learn that they have earned a lot of recognition, respect and gratitude. Just because the controller usually is a voice, and therefore more often than not remains largely anonymous does not mean that pilots don’t appreciate them.

And Chip, when I did my IF rating, the training was very intensive (and intense). The first lessons often took place in a simulator. Not the original Link Trainer, but a Frasca. It had no motion but otherwise had all the instruments that were installed in contemporary light aircraft that were IFR equipped. The instructors were professionals who worked as simulator instructors with KLM*. They could disable the ADI in the Frasca. In the situation that I described, the instructor blanked off the artificial horizon during training specifically for the instrument rating in an aircraft. This part of the training took place as part of a curriculum and not during the very first lessons. The training was usually conducted in VMC with the pupil using a hood that virtually prevented him or her to look outside, the hood restricted the field of vision to the instrument panel only. The instructor, of course, did not wear this hood and remained in full control.

In the old days a system was used whereby the cockpit windows were covered with a transparent film, I believe it was blue. The student was given yellow-tinted glasses (or was it the other way around? I forgot). Anyway, the effect of the combination of blue and yellow was that the student could not see anything outside. The instructor’s view, without the glasses, was still unobstructed. In some aircraft, only the left windscreen was covered with film anyway.

During an instrument approach we would continue till MDA or DH, the instructor would either call “Go around” or “Runway”. In the latter case, we whipped the glasses off our nose and continue for a normal landing, but on a few occasions the instructor would call “Continue”. We would be expected to fly without outside visual reference virtually until we touched down. If necessary the instructor would assist with the landing flare.

*KLM no longer employs specific simulator instructors, sim. training now is conducted by line pilots with a type instructor’s qualification.

Rudy — I was discussing what was taught during private training, not IF; teaching someone how to handle one emergency-from-bad-judgment should assume the rest of the universe is normal, so they get maximum benefit out of a brief lesson. I won’t argue standards for instrument training; the more I think about my one IFR flight as PF (a week or so after I got my rating), the more I think I was foolish to take on that flight (through New York City airspace, with a passenger) even if I had had several hours of real instrument flying before.

Chip, that is clear now. You are right: Flying on instruments, even when IFR rated, is one thing. To fly IFR (IMC?) through very busy airspace, including a TMA serving major international airports, can be very demanding and actually should not be attempted unless the pilot is experienced enough to handle the workload, which can be very high.

Airline pilots, arriving from, or departing to a destination on another continent, usually don’t have a lot of time to waste. Clearances are issued quick and fast. ATC expects them all to understand the R/T and experienced airline pilots develop a knack for cutting in, without cutting anyone off. A novice who has trouble understand the clearances, is asking “say again?” or cuts in on other transmissions is more than an irritation, he or she can actually cause an airliner to miss a clearance and therefore getting an often costly diversion. Meanwhile, the novice may get him- or herself in trouble because (s)he can get confused, which will cause additional pressure on ATC. Airline pilots often develop a dislike for amateurs.

The best way, of course, is to fly with another competent pilot who can act as a copilot. But then, this may require some additional training.

Multi-crew operation is another chapter again, and should include CRM.

I did operated the Cessna 310 single-crew and into major international airports, such as Frankfurt, Hanover, Amsterdam, London Gatwick, Madrid, Copenhagen, Barcelona, Warsaw, Belgrade, Palma de Mallorca (extremely busy in summer !), etc. But the aircraft had a very good autopilot so I could let “George” do the flying and concentrate on the R/T and navigation.